Paul Krichell

| Paul Krichell | |||

|---|---|---|---|

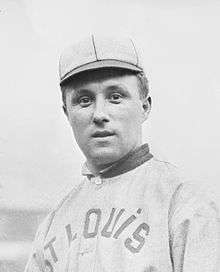

Paul Krichell during the 1911 season | |||

| Catcher | |||

|

Born: December 19, 1882 Paris, France | |||

|

Died: June 4, 1957 (aged 74) New York City | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| May 12, 1911, for the St. Louis Browns | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| September 22, 1912, for the St. Louis Browns | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .222 | ||

| Home runs | 0 | ||

| RBIs | 16 | ||

| Teams | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

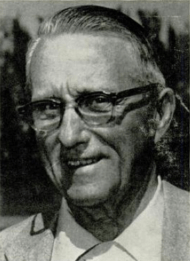

Paul Bernard Krichell (December 19, 1882 – June 4, 1957) was a Major League Baseball catcher, best known for being the head scout for the New York Yankees for 37 years until his death. Krichell's talent evaluations and signings played a key role in building up the Yankees' run of success from the Murderers' Row teams of the 1920s to the 1950s teams led by Casey Stengel.[2]

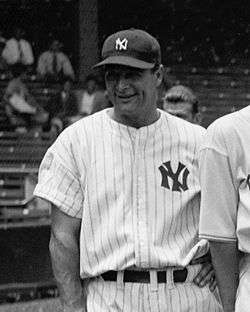

Krichell began his professional career in the minor leagues, playing as the reserve catcher for the St. Louis Browns before a serious injury threatened his career. He continued to play in the minor leagues and began to move into coaching before Yankees manager Ed Barrow signed him as a scout in 1920. Considered one of the greatest scouts in baseball history, Krichell signed over 200 players who later played professional baseball,[3] including future Baseball Hall of Famers Lou Gehrig, Hank Greenberg, Phil Rizzuto, Whitey Ford, and Tony Lazzeri. His recommendation of Stengel as the Yankees manager was instrumental in Stengel's appointment in 1948. Barrow called Krichell "the best judge of baseball players he ever saw".[4]

Early life

Krichell was born in Paris, France, the son of a German cabinetmaker and youngest of nine children. He grew up in The Bronx, near Yankee Stadium.[3] Krichell made his professional baseball debut in 1903 as a catcher with the Ossining, New York club in the Hudson River League's inaugural season.[1] He moved to the Hartford Senators of the Connecticut League in 1906 and spent most of the following three years with the Newark Indians of the Eastern League. For the latter part of the 1909 season and the whole of 1910, Krichell played for the Montreal Royals at third base. In 1910, he played 102 games for the team, achieving a batting average of .249 and hitting 14 doubles.[5][6] Krichell began his long association with manager Ed Barrow that year when the latter took charge of the Royals.[5]

Playing and managing career

In 1911, Krichell joined the St. Louis Browns as a reserve catcher, playing 28 games with a .232 batting average, 19 hits and 8 runs batted in during 82 at bats.[7] The following year, he managed 59 games while sharing catching duties with Jim Stephens.[8] In 161 at bats, Krichell achieved 35 hits and a .217 batting average.[7] His fielding percentage was .959 that season.[7] Ty Cobb of the Detroit Tigers stole second, third, and home plate in the same inning of a game while Krichell was catching.[9] In a later game, Krichell's arm was almost detached from his shoulder when Cobb spiked his arm with his cleats during a play at home plate. The injury effectively ended Krichell's major league career.[10]

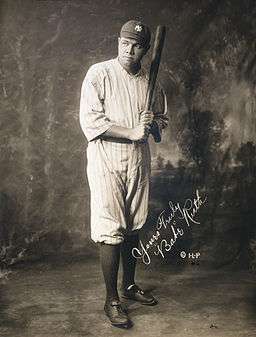

After the 1912 season, the Browns released Krichell, but after recovering from his injury, he played six seasons in the minor leagues. He was the starting catcher for the Buffalo Bisons in 1914 when Babe Ruth made his professional debut with the Baltimore Orioles, hitting a double and a single against his pitching.[11] From 1917 to 1918, Krichell served as manager for Bridgeport of the Eastern League, making several playing appearances over the two seasons.[12] He resigned on June 27, 1918, after two wins were forfeited when he used a player not under contract.[13] He worked in the shipyards during the First World War.[11] During the offseason, Krichell became the owner of a saloon popular with players in the Bronx,[14] before Prohibition forced Krichell to close and return to baseball.[14] For the 1919 season, he coached the New York University baseball team,[12] and after the season ended, he signed with Ed Barrow to become a coach and scout for the Boston Red Sox in the following season.[15]

Scouting career

Prior to the 1921 season, Barrow was appointed general manager of the New York Yankees and requested that Krichell join him as a full-time scout. At the time, the Yankees had a two-man scouting rotation, and Barrow believed the appointment of Krichell would improve the scouting staff.[3] The first player signed by Krichell was Hinkey Haines, an outfielder from Penn State University.[1] He signed catcher Benny Bengough from Buffalo of the International League,[3] and Charlie Caldwell, a Princeton University graduate. Caldwell was used mainly as a batting practice pitcher, appearing in just three games in his major league career. During one practice, Caldwell fractured Wally Pipp's skull with a high fastball,[16] allowing Lou Gehrig to assume Pipp's place in the starting lineup.[17]

Discovery of Gehrig

Early in the 1923 season, while traveling to New Brunswick, New Jersey for a baseball game between Columbia University and Rutgers University,[18] Krichell shared a train with the manager of the Columbia squad, Andy Coakley.[19] They discussed Lou Gehrig, a left-handed pitcher on his squad who could also hit,[1][19] and later that day, Gehrig hit two home runs in three at-bats.[19] Following the game, Krichell spoke with Barrow, saying he had found the "next Babe Ruth".[20] Skeptical, Barrow sent Krichell to watch Columbia's next game against New York University,[19] where Gehrig hit a home run that reportedly went out of the stadium.[21] After the game, Krichell persuaded Gehrig to sign for the Yankees for $2,000 ($30,000 in 2010) for the remainder of 1923, with a $1,500 bonus ($20,000 in 2010).[20] Krichell also asked Gehrig to give up pitching to focus on being a hitter.[22]

After joining up with the team for batting practice in June 1923, Gehrig was sent by Yankees manager Miller Huggins to the Hartford Senators. After a good start, Gehrig went through a long slump and suffered depression which led him to consider quitting baseball.[23] Upon hearing this, Krichell was sent to Hartford to speak with the star player. He discovered that Gehrig was drinking, boosted his confidence and gave him batting advice, including one of Ty Cobb's batting tricks.[24] Gehrig started hitting again, and eventually joined the Yankees.

Later signings

1920s

Before the 1925 New York Yankees season, Babe Ruth collapsed at a train station in Asheville, North Carolina. Krichell's actions may have saved Ruth's life. On the instructions of Huggins, Krichell drove Ruth to hospital,[25] before traveling with Ruth by train to New York, where Ruth had emergency surgery for an "intestinal abscess" that left him hospitalized for six weeks.[26]

The same year, Krichell went to Hartford, Connecticut to sign shortstop Leo Durocher for a $7,500 bonus ($90,000 in 2010).[27] When the deal was concluded, Barrow sent Krichell to Salt Lake City to watch young second baseman Tony Lazzeri, who played for the Salt Lake Bees of the Pacific Coast League and hit 60 home runs and achieved over 200 RBIs the previous season.[28] The Bees were asking for $50,000 ($620,000 in 2010), but several scouts placed his value ten times lower.[3] The Chicago Cubs were given the option to sign him for a discounted rate, but declined because he had epilepsy.[3][29] Krichell saw promise in the player and convinced Barrow to buy him.[3] Around the same time, he helped acquire shortstop Mark Koenig from the Minneapolis Millers.[30] These Krichell signings formed part of the 1927 New York Yankees team, considered by many to be the greatest team ever assembled.[31] Four of the starters in this squad were signed by Krichell, including three-quarters of its infield and Mike Gazella, its main backup, who signed for $500 in 1923 ($10,000 in 2010).[32] The Yankees took just four games to defeat the Pittsburgh Pirates and win the 1927 World Series.[33]

To assist at practice for the 1927 season, Krichell signed Billy Werber from Duke University.[34] He left the team after a month, but re-signed after graduating in 1930. During that time, Krichell was involved in what is considered one of the worst deals from the era. Barrow asked him to travel to Durham, North Carolina to negotiate with the Durham Bulls for an outfielder named Dusty Cooke.[3] Neither Krichell nor Barrow had seen Cooke; he was believed to be a great hitter, even though he had hardly played for the Bulls.[3] The Yankees signed him for $15,000 ($200,000 in 2010), beating the Cleveland Indians' offer of $12,500 ($160,000 in 2010) and an unnamed player in exchange.[3] Cooke turned out to be an injury-prone backup outfielder, and the Yankees gave up on both Cooke and Werber. After the 1933 season, the two were traded to the Boston Red Sox for cash considerations.[3]

In the summer of 1929, Krichell discovered Hank Greenberg while on a scouting trip in Massachusetts. Krichell believed Greenberg would be the next Lou Gehrig.[35] Krichell offered Greenberg a $10,000 contract ($130,000 in 2010) on the spot based on his potential and knowing the Yankees were looking for Jewish players to increase their Jewish fanbase.[35] Greenberg discussed the deal with his father but declined it because he knew his opportunities would be limited by the presence of Gehrig as first baseman.[36] Subsequently, he signed with the Detroit Tigers.

1930s

In the early 1930s, Krichell focused on Ivy League pitchers, saying he preferred signing pitchers who could think.[3] From Harvard University, he signed Charlie Devens later saying he could have been great had he continued to play baseball,[3] and from Yale University, he scouted pitcher Johnny Broaca who seemed to be heading for stardom after winning 12 games in his first three seasons with the Yankees, but suddenly retired to become a professional boxer.[37] In 1935, a local scout who worked with Krichell placed Long Island University pitcher Marius Russo in a semi-professional team.[38][39] When Krichell deemed Russo ready, he signed with the Yankees for $750,[39] twice becoming a 14-game winner and being an All-Star in 1941 before injuring his arm. Other Krichell signings from this period included Johnny Murphy, Hank Borowy and Johnny Allen. Murphy, a relief pitcher and four time saves leader, was signed while still in high school in the Bronx and at Krichell's behest, the Yankees followed Murphy's education at Fordham University, where he gained baseball experience.[40] Krichell signed Borowy from Fordham University for $8,500 and the player later became the ace for the Yankees during the wartime era.[3] Krichell supposedly discovered Allen by a chance encounter when Allen worked as a desk clerk at a Sanford hotel. The story said he recognized Krichell as a scout, told him that he was a pitcher, and that he wanted to try out. Krichell agreed, and impressed by Allen's ability, signed him to a minor league contract.[41] However, in an interview with J. G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News, Krichell said while he signed Allen, he did not discover him.[11]

Aside from his Ivy League pitcher focus, Krichell also unearthed several position players. He signed Charlie Keller, a highly touted prospect playing for the University of Maryland. To encourage Keller to sign, Krichell met and had dinner with his family.[3] In 1937, Krichell signed shortstop Phil Rizzuto, who had tried out with the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants, but was dismissed by them on the grounds that he was too small.[42] Even so, Krichell decided to look at the infielder and was impressed by the way Rizzuto accomplished double plays; his technique reminded Krichell of Leo Durocher, one of his favorite players.[3] He signed Rizzuto for $75 a month and sent him to the Yankees' farm club in Bassett, Virginia.[43]

1940s–1950s

Krichell's next target was second baseman Snuffy Stirnweiss from the University of North Carolina. He initially tried to convince him to bypass football for baseball, but the player refused until his father's death soon after his college graduation altered his priorities, leaving him as the sole supporter of his mother and younger brother.[44] Krichell signed him to a contract soon afterwards. In a mass tryout for the Yankees team, Krichell scouted first baseman Whitey Ford. Krichell realised Ford had a strong arm, and recommended he tried pitching. Developing an effective fast curveball, Ford helped his team win the New York City sandlot ball championship, and was signed by Krichell for $7,000 in 1947 ($70,000 in 2010).[45] Ford later became a Hall of Famer and an ace of the Yankees for most of the 1950s and 1960s.

Krichell played a factor in signing future All-Star Tommy Byrne.[46] He was referred by one of his scouts, Gene McCann, to see Byrne pitch for Wake Forest University.[46] Impressed with what he saw, Krichell signed him for $10,000 ($160,000 in 2010).[47] He also signed Red Rolfe and Vic Raschi.[1] Krichell oversaw the expansion of the New York Yankees scouting staff from two men to more than twenty part-time scouts by 1957.[1] Among the scouts he hired for the Yankees were former players Babe Herman, Atley Donald, Jake Flowers and Johnny Neun.[48] As he hired more scouts, Krichell reduced his own role, becoming the chief scout and regional scout for the New England area.[48]

In 1948, Krichell was involved in a minor scandal. Harry Nicolas was a high school baseball star in Long Island. The Yankees sent Krichell to scout him and offered him a contract with a blank check, being willing pay up to $20,000 for his services. As Nicolas was still in high school, the Yankees were fined $500 by Happy Chandler, the Commissioner of Baseball.[49] Nicolas never reached the Majors. However, Krichell's recommendation of Casey Stengel for manager of the Yankees in 1948 was instrumental in their front office hiring him.[4]

Final days

In 1954, Krichell was honored by the Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA) with the William J. Slocum Memorial Award. Named after the former head sportswriter of the New York Journal American and president of the BBWAA, the award honored his longevity in baseball.[1] The final players Krichell signed were two bonus babies: infielder Tom Carroll from Notre Dame University and Frank Leja, an 18-year-old first baseman. Krichell advised the Yankees staff to sign Carroll for $30,000 ($240,000 in 2010)[1] and he thought Leja could be the next Gehrig, but both flopped.[50] By the time he retired, he was the most experienced employee still working for the Yankees.[1]

Krichell died on June 4, 1957 at his home in the Bronx after a lengthy illness.[1] He had surgery for Crohn's disease in 1955 after losing 60 pounds in 60 days.[3] His wife of 50 years, Mary, died earlier in the year.[1] He had one daughter, Caroline, and four grandchildren at the time of his death.[1]

Scouting style

When he first started his scouting career, Krichell followed the example of early baseball scouts. He traveled with the Yankees for spring training to view his signees playing baseball. When the Yankees traveled north to begin their season, Krichell usually followed.[18] He also scouted the local newspapers to look for games in which potential prospects were playing.[19]

Later, his style of scouting was used as a blueprint by scouts to evaluate players. He usually ignored the obvious tools such as ability to hit, size, speed, and human power, saying that "any dope" could see it.[3] When he scouted a prospect, his top priority was checking that the subject could handle the pressure of playing Major League Baseball.[51] When he got word of a promising player, he went to see him play. If Krichell liked what he saw, he discussed the player's goals and motivation with him and his family.[3] He decided whether the player was ready for the Yankees or one of their farm teams to use. He tended to take a risk with players passed by other teams.[52] He discounted some of a player's weaknesses if their remaining skills were up to par, for example with Tony Lazzeri, who was a poor fielder.[3] Krichell also was one of the first to notice that intelligence mattered in a game filled with uneducated people. Most of his signings were college graduates who Krichell believed could take advantage of their ability to think.[53]

At other times, Krichell collected some of the best prospects in an area, normally 300 or more, and put them through a four-day workout. It normally consisted of practice in the morning and a full game in the afternoon.[54] There, Krichell and his staff sorted though players they believed could become useful in the organization, and dropped those they thought lacked motivation. The few players who survived the workout were assigned by Krichell to the Yankees Minor League hierarchy.[3]

Legacy

Krichell is considered one of the greatest scouts in baseball history.[55] Birdie Tebbetts, a member of the Veterans Committee in the 1980s, led a campaign to have Krichell, along with fellow scouts Charlie Barrett and Hugh Alexander, inducted to the Baseball Hall of Fame.[56] Under Hall of Fame rules, scouts are not eligible for induction.[57] Tibbets appealed to the Hall of Fame Board of Directors every year from 1981 to 1986 to make the three scouts members of the Hall of Fame, but with no success.[56] In The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, James awards the Paul Krichell Talent Scout Award to an example of a team that has a good chance of signing a player who later becomes a star, who they end up passing on as the result of poor scouting.[58]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Paul. B. Krichell of Yankees dies". The New York Times. June 5, 1957. Retrieved February 4, 2010. (subscription required)

- ↑ James (1995), p. 217

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Caremer, Dave (July 1957). "36 Years as a Yankee". Baseball Digest. pp. 27–39. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- 1 2 Gallagher, p. 343

- 1 2 Levitt, p. 75

- ↑ "Paul Krichell Minor League Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- 1 2 3 "Paul Krichell". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ "1912 St. Louis Browns". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ↑ Eig, p. 38-40

- ↑ Cobb, Ty; Al Stump (1993). My Life in Baseball: The True Record. University of Nebraska Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-8032-6359-7.

- 1 2 3 J. G. Taylor Spink (April 20, 1939). "Criss Crossing Talent Trails With Krichell". The Sporting News. p. 8.

- 1 2 Levitt, p. 188

- ↑ "Yanks's Lose in 9th, Fall Back on Race". Hartford Courant. June 18, 1918. p. 10.

- 1 2 Meany, Thomas (1951). Baseball's greatest pitchers. A.S. Barnes. p. 101.

- ↑ Frommer, Harvey (1992). Five O'Clock Lightning: Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and The Greatest Team in History. Wiley Publishers. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-471-77812-7.

- ↑ Eig, p. 66

- ↑ Eig, p. 67

- 1 2 Eig, p. 38

- 1 2 3 4 5 Eig, p. 39

- 1 2 Frommer, p. 44

- ↑ Eig, p. 40

- ↑ Maisel, Ivan (April 12, 1982). "Scouts Stay Persona Non Grata To Baseball's Hall Of Fame Committee". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ↑ Eig, pp. 41, 44, 48

- ↑ Eig, p. 49

- ↑ Montville, Leigh (2007). The Big Bam: The Life and times of Babe Ruth. DoubleDay Books. p. 202. ISBN 0-385-51437-9.

- ↑ Spector, Jessie (June 19, 2005). "Touching Base. Close Calls. One-run games make big difference to even best teams.". New York Daily News.

- ↑ Lowenfish, Lee (2009). Branch Rickey: Baseball's Ferocious Gentleman. University of Nebraska Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-8032-2453-7.

- ↑ Frommer, p. 49

- ↑ Neyer, Rob (2000). Baseball Dynasties: The Greatest Teams of All Time. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 95. ISBN 0-393-04894-2.

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 123

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 5

- ↑ Frommer, p. 56

- ↑ "1927 World Series – New York Yankees Over Pittsburgh Pirates (4–0)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ Cranston, Mike (June 14, 2008). "Oldest living ex-major leaguer has stories to tell". USA Today. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- 1 2 Eig, p. 133

- ↑ Eig, p. 134

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 38

- ↑ Madden, Bill (2004). Pride of October: What It Was to Be Young and a Yankee. Warner Books. p. 26. ISBN 0-446-69269-7.

- 1 2 Madden, p. 27

- ↑ Daniel M. Daniel (September 16, 1937). "Grandma Murphy Patches Up Yankee Pitching Staff". The Sporting News. p. 3.

- ↑ Schneider, Russell (2004). The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 128. ISBN 0-8032-6359-7.

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 342

- ↑ Madden, p. 4

- ↑ Dexter, Charles (January 1948). "Bronx Express:Snuffy Stirnweiss". Baseball Digest. p. 4. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Staples, Billy (2007). Before the Glory: 20 Baseball Heroes Talk about Growing Up and Turning Hard Times Into Home Runs. Health Communications Inc. pp. 306–308. ISBN 0-7573-0626-8.

- 1 2 Staples, p. 45

- ↑ Staples, p. 46

- 1 2 Shaplen, Robert (September 20, 1954). "New York Yankee Organization". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ↑ Jack Lang (January 28, 1948). "Harry Nicolas to Decide on Graduation January 30". The Sporting News. p. 3.

- ↑ Gallagher, p. 250

- ↑ Voigt, p. 177

- ↑ Berger, p. 99

- ↑ Graham, p. 141

- ↑ Madden, p. 5

- ↑ Tranchtenburg, p. 175

- 1 2 Feldman, Jay (February 5, 1990). "Make Scouts Eligible For Cooperstown". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ↑ Kuenster, John (December 1992). "Scouts and Coaches Should Be Eligible for the Hall of Fame". Baseball Digest. p. 17.

- ↑ James (2003), p. 256

Bibliography

- Berger, Lance A.; Dorothy R. Berger (2005). Management Wisdom from the New York Yankees' Dynasty. Wiley Publishers. ISBN 0-471-71554-9.

- Blackwell, Peter (1983). American Baseball: From the Commissioners to Continental Expansion, Volume 3. Penn State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00330-8.

- Eig, Jonathan (2005). Luckiest man: the Life and Death of Lou Gehrig. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-4591-1.

- Gallagher, Mark (2003). The Yankee Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing L.L.C. ISBN 1-58261-683-3.

- Graham, Frank (2003). A Farewell to Heroes. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2491-1.

- James, Bill (2003). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. Simon & Schuster. p. 256. ISBN 0-684-80697-5.

- James, Bill (1995). Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80088-8.

- Levitt, Daniel R. (2008). Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees' First Dynasty. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2974-7.

- Trachtenberg, Leo (1995). The Wonder Team: The True Story of the Incomparable 1927 New York Yankees. Popular Press. ISBN 0-87972-677-6.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or The Baseball Cube, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)