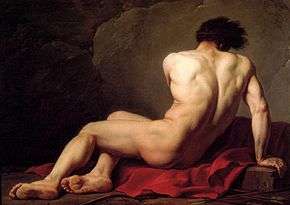

Patroclus

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Homer's Iliad, Patroclus (/pəˈtroʊkləs, pəˈtrɒkləs/; Ancient Greek: Πάτροκλος Patroklos "glory of the father") was the son of Menoetius, grandson of Actor, King of Opus, and Achilles' beloved comrade and brother-in-arms.

Life and Death

According to Hyginus, Patroclus is the child of Menoetius and Philomela.[1] Homer also references Menoetius as the individual who gave Patroclus to Peleus.[2] Menoetius is the son of Actor, King of Opus in Locris by Aegina.[3] Aegina was a daughter of Asopus and mother of Aeacus by Zeus. Aeacus was father of Peleus, Telamon and Phocus. Actor was a son of Deioneus, King of Phocis and Diomede. His paternal grandparents were Aeolus of Thessaly and Enarete. His maternal grandparents were Xuthus and Creusa, daughter of Erechtheus and Praxithea.

During his childhood, Patroclus had killed another child in anger over a game. Menoetius gave Patroclus to Peleus, Achilles' father, who named Patroclus one of Achilles' "henchmen" as Patroclus and Achilles grew up together.[2] Patroclus acted as a male role model for Achilles, as he was both older than Achilles and wise regarding counsel.[4]

According to the Iliad, when the tide of war had turned against the Greeks and the Trojans were threatening their ships, Patroclus convinced Achilles to let him lead the Myrmidons into combat. Achilles consented, giving Patroclus the armor Achilles had received from his father, in order for Patroclus to impersonate Achilles. Achilles then told Patroclus to return after beating the Trojans back from their ships.[5] Patroclus defied Achilles' order and pursued the Trojans back to the gates of Troy.[6] Patroclus killed many Trojans, including a son of Zeus, Sarpedon.[7] While battling, Patroclus' wits were removed by Apollo, after which Patroclus was hit with the spear of Euphorbos. Hector then killed Patroclus by stabbing him in the stomach with a spear.[8]

Achilles retrieved the body, which had been stripped of armor by Hector and protected on the battlefield by Menelaus and Ajax.[9] Achilles did not allow for the burial of Patroclus' body until the ghost of Patroclus appeared and demanded burial in order to pass into Hades.[10] Patroclus was then cremated on a funeral pyre, which was covered in the hair of his sorrowful companions. As the cutting of hair was a sign of grief while also acting as a sign of the separation of the living and the dead, this points to how well-liked Patroclus had been.[11] The ashes of Achilles were said to have been buried in a golden urn along with those of Patroclus by the Hellespont.[12]

Relationship to Achilles

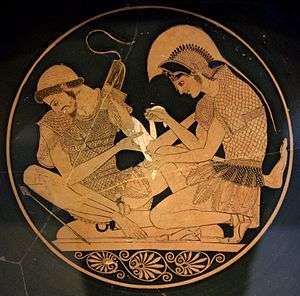

Although Homer does not mention it, there is debate whether or not Achilles and Patroclus had a homosexual relationship. Morales and Mariscal point out that there are several other authors who do draw a romantic connection between the two characters, such as Aeschylus and Phaedrus, who even refers to Achilles as the eromenos. Morales and Mariscal continue stating, "there is a polemical tradition concerning the nature of the relationship between the two heroes".[13] According to Grace Ledbetter, there is a train of thought that Patroclus could have been a representation of the compassionate side of Achilles, who was known for his rage. In fact, the first line of Homer's Iliad mentions Achilles' anger. In contradiction to Morales and Mariscal putting Achilles in the role of the younger male, Ledbetter connects the way that Achilles and his mother Thetis communicate to the communication between Achilles and Patroclus. Ledbetter does so by comparing how Thetis comforts the weeping Achilles in Book 1 of the Iliad to how Achilles comforts Patroclus as he weeps in Book 16. Achilles uses a simile containing a young girl tearfully looking at her mother to complete the comparison. Ledbetter believes this puts Patroclus into a subordinate role to that of Achilles.[14]

James Hooker describes the literary reasons for Patroclus' character within the Iliad. He states that another character could have filled the role of confidant for Achilles, and that it was only through Patroclus that we have a worthy reason for Achilles' wrath. Hooker claims that without the death of Patroclus, an event that weighed heavily upon him, Achilles' following act of compliance to fight would have disrupted the balance of the Iliad.[15] Hooker describes the necessity of Patroclus sharing a deep affection with Achilles within the Iliad. According to his theory, this affection allows for the even deeper tragedy that occurs. Hooker argues that the greater the love, the greater the loss. Hooker continues to negate Ledbetter's theory that Patroclus is in some way a surrogate for Achilles; rather, Hooker views Patroclus' character as a counterpart to that of Achilles. Hooker reminds us that it is Patroclus who pushes the Trojans back, which Hooker claims makes Patroclus a hero, as well as foreshadowing what Achilles is to do.[15]

Achilles and Patroclus grew up together after Menoitios gave Patroclus to Achilles' father, Peleus. During this time, Peleus named Patroclus one of Achilles' "henchmen".[16]

While Homer's Iliad never once explicitly stated that Achilles and his close friend Patroclus were lovers, this concept was asserted by some later authors.[17][18][19] Aeschines asserts that there was no need to explicitly state the relationship as a romantic one,[19] for such "is manifest to such of his hearers as are educated men."[20] Later Greek writings such as Plato's Symposium, the relationship between Patroclus and Achilles is discussed as a model of romantic love.[21] However, Xenophon, in his Symposium, had Socrates argue that it was inaccurate to label their relationship as romantic. Nevertheless, their relationship is said to have inspired Alexander the Great in his close relationship with his companion Hephaestion.[17][22] After Patroclus killed Clysonymus, Patroclus and his father fled to Peleus palace. Patroclus then grew up with Achilles. Their relationship was so strong that it was as if they were more than brothers. However, Achilles was much younger than Patroclus.[21] This reinforces Dowden's explanation of the relationship between an eromenos, a youth in transition, and an erastes, an older male although having recently made the same transition.[23] Dowden also notes the common occurrence of such relationships as a form of initiation.[24]

Further reading

- Evslin, Bernard (2006). Gods, Demigods and Demons. London, ENG: I. Tauris.

- Michelakis, Pantelis (2007). Achilles in Greek Tragedy. Cambridge, ENG: Cambridge University Press.

- Kerenyi, Karl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. London, ENG: Thames and Hudson. pp. 57–61, et passim.

- Sergent, Bernard (1986). Homosexuality in Greek Myth. Boston, MA, USA: Beacon Press.

References

- ↑ Hyginus. Fabulae.

- 1 2 Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 474 b.23 l.85.

- ↑ Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 274 b. 11 l. 384.

- ↑ Finlay, Robert (1980). Patroklos, Achilleus, and Peleus: Fathers and Sons in the Iliad. The Classical World. pp. 267–273.

- ↑ Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 353 b. 16 l. 64–87.

- ↑ Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Boston: Little. p. 140.

- ↑ Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 363 b. 16 l. 460.

- ↑ Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 373 b. 16 l. 804–822.

- ↑ Bulfinch, Thomas (1985). The Golden Age. London: Bracken Books. p. 272.

- ↑ Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 474 b.23 l. 69–71.

- ↑ Martin, Richard (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 561.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh (1911). "Achilles". Encyclopaedia Britannica (11th ed.).

- ↑ Sanz Morales, Manuel; Mariscal, Gabriel Laguna (May 2003). "The Relationship Between Achilles and Patroclus According to Chariton of Aphrodisias". Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Ledbetter, Grace (December 1, 1993). "Achilles' Self-Address". American Journal of Philology.

- 1 2 Hooker, James (January 1, 1989). "Homer, Patroclus, Achilles". Symbolae Osloenses.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 474.

- 1 2 Martin, Thomas R. (2012). Alexander the Great: The Story of an Ancient Life. Cambridge, ENG: Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0521148448.

[See next reference for a relevant quotation.]

- ↑ As Martin (2012), op. cit., argues (see preceding footnote), "The ancient sources do not report, however, what modern scholars have asserted: that Alexander and his very close friend Hephaestion were lovers. Achilles and his equally close friend Patroclus provided the legendary model for this friendship, but Homer in the Iliad never suggested that they had sex with each other. (That came from later authors.) If Alexander and Hephaestion did have a sexual relationship, it would have been transgressive by majority Greek standards…" (p. 99f).

- 1 2 Boswell, John (1980). Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 47.

- ↑ Aeschines (1958). The Speeches: Against Telemarchus, On the Embassy, Against Ctesiphon. Translated by Charles Darwin Adams. London: Harvard University Press. p. 115.

- 1 2 Plato (1987). The Symposium. Translated by Walter Hamilton. Penguin Books. pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Fox, Robin Lane (2005). The Classical World. Penguin Books. p. 235.

- ↑ Dowden, Ken (1992). The Uses of Greek Mythology. London: Routledge. p. 112.

- ↑ Dowden, Ken (1992). The Uses of Greek Mythology. London: Routledge. p. 114.

External links

Media related to Patroclus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Patroclus at Wikimedia Commons

| Achilles and Patroclus myths as told by story tellers |

|---|

| Bibliography of reconstruction: Homer Iliad, 9.308, 16.2, 11.780, 23.54 (700 BC); Pindar Olympian Odes, IX (476 BC); Aeschylus Myrmidons, F135-36 (495 BC); Euripides Iphigenia in Aulis, (405 BC); Plato Symposium, 179e (388-367 BC); Statius Achilleid, 161, 174, 182 (96 AD) |