Patolli

Patolli (Nahuatl: [paˈtoːlːi]) or patole (Spanish: [paˈtole]) is one of the oldest known games in America. It was a game of strategy and luck, and very much a game of commoners and nobles alike. It was reported by the conquistadors that Montezuma often enjoyed watching his nobles play the game at court.

History

Patolli or variants of it was played by a wide range of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures and known all over Mesoamerica: the Teotihuacanos (the builders of Teotihuacan, ca. 200 BC - 650 AD) played it as well as the Toltecs (ca. 750 - 1000), the inhabitants of Chichen Itza (founded by refugee Toltec nobles, ca. 1100 - 1300), the Aztecs (who claimed Toltec descent, 1168 - 1521), and all of the people they conquered (practically all of Mesoamerica, including the Zapotecs and the Mixtecs). The ancient Mayans also played a version of patolli. Anthropologist E. Adamson Hoebel (1966) says the Aztec patolli derives from the East Indian game of pachisi,[4] but R.B. Lewis of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Illinois (1988) says that the similarity between the two games is due to the limitations of a board game,[5] meaning the two games were independently derived.

Players

Patolli is a race/war game with a heavy focus on gambling. Players would meet and inspect the items each other had available to gamble. They bet blankets, maguey plants, precious stones, gold adornments, food or just about anything. In extreme cases, they would bet their homes and sometimes their family and freedom. Agreeing to play against someone was not done casually as the winner of the game would ultimately win all of the opponent's store of offerings. Each player must have the same number of items to bet at the beginning of the game. The ideal number of items to bet is six, although any number would be acceptable as long as each player agreed. The reason for having at least six bits of treasure is that each player has six markers that will traverse the game board. As each marker successfully completes the circuit around the board, the opponent is required to hand over ownership of an item from his or her treasure.

Once an agreement is made to play, the players prepare themselves by invoking the god of games, Macuilxochitl.

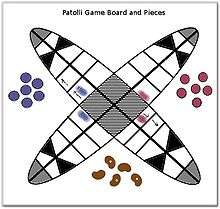

Gameplay and Game Pieces

The goal of patolli was to move six game pieces through the specified squares.[2] The object of the game is for a player to win all of the opponent's treasure. To do this, the players may need to play more than one round of the game. In order to complete a round, a player needs to get all of the six game markers from the starting queue position to the ending square position on the game board before the other player.

Five or six black beans were used as dice.[2] Dice were also used.[1] If a toss results in all the beans standing on their sides, then the tosser wins all the goods bet by both parties.[2]

The game pieces were six red and six blue pebbles;[2] each player controlled one color. Beans, kernels of maize, or even pieces of jade could also be used instead of pebbles.

In order to get one of the stone markers on the board, the player tosses five specially prepared black beans on the game area. Each black bean has one side marked with a hole. Thus tossing the black beans would result in several black beans showing this white mark and others showing a blank side. In order to get on the game board, one black beans would have to land with the hole face up and all the others face down (getting a score of one). The players take turns tossing. Once a player is able to get on the board, the game begins and the player is allowed to place one of the game markers from the queue onto the starting square of the game board.

The game mat had 52 squares arranged in an "X" shape, painted on it with liquid rubber.[2] The game board could be drawn on a bit of leather or on a straw mat and decorated with colored dye, or carved into the floor or table top.

The four landing positions in the middle of the X are a special area. A player who lands a marker on the opponent's marker in this area can remove the opponent's marker from the game board and put it back into the opponent's starting queue. The opponent is then required to transfer ownership of one of the items being bet.

Another special area is marked by two darker triangular shapes near the end of each arm of the X. If a player should land a marker inside one of these triangular areas, the player must transfer ownership of an item to the opponent.

There are two special squares marked at the end of each arm of the X. A player who lands on one of these squares must roll the black beans and take another turn.

After a player has a game marker on the game board, the player must move one of the game markers the same number of times as there are holes showing from the toss. If the player cannot move because he would overshoot the ending square or land on an occupied spot, then he loses the turn.

If the toss shows five holes, then the player must choose one game marker to move ten spaces.

The god Macuilxochitl is considered to be participating in the game.[2] The Magliabechiano codex says, "Patolli's god was Macuilxochitl, deity of music, dance, gambling and games, called God of the Five Flowers. Players are required to give Macuilxochitl an item if a toss of the beans results in no holes (all blank sides) showing. A space is reserved above the game board for these items. The winner of the round will receive the treasure located in this space as a gift from Macuilxochitl."

Spanish Conquest

The Spanish priests forbade the game during the Spanish conquest of Mexico, possibly due to people selling themselves and their families into slavery over it. They were even known to have burned the hands of people caught playing the game.

See also

References

- 1 2 Rees, R. (2006). Understanding people in the past: The Aztecs. Reed Elsevier Inc.: Chicago ISBN 1-403-48749-9 pp. 35

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Berdan, F.F. & Anawalt, P.R. (1997).The essential Codex Mendoza. University of California Press: California. ISBN 0-520-20454-9

- ↑ 9 game of patolli. (2001). McGraw Hill. Retrieved August 29, 2012, from link

- ↑ Hoebel, E.A. (1966). Anthropology (3rd ed.). University of Minnesota: USA. P.76. "... the diffusion of the ancient East Indian game of pachisi into prehistoric America, where it appeared among the Aztecs as patolli and in various other forms among other Indians."

- ↑ Lewis, R. B. (1988). Old World dice in protohistoric United States. In Current Anthropology. 29(5) pg.766

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Patolli. |