Panbabylonism

Panbabylonism was a hyperdiffusionist school of thought within Assyriology and religious studies that considered the cultures and religions of the middle east and civilization in general to be ultimately derived from Babylonian astronomy and astrology. A related school of thought is the Bible-Babel school, which regarded the Hebrew Bible and Judaism to be directly derived from Mesopotamian (Babylonian) mythology.[1] Both theories were popular in Germany, and the height of Panbabylonism was from late 19th century to World War I. Panbabylonist thought largely disappeared from legitimate scholarship after the death of one of its greatest proponents, Hugo Winckler.[1] Modern Panbabylonist arguments are generally considered pseudoscientific.[1]

Creation myths

Panbabylonists believe the creation myth in the Book of Genesis came from older Mesopotamian creation myths. The Mesopotamian creation myths are recorded in the Enûma Eliš (or Enuma Elish), the Atra-Hasis, the 'Eridu Genesis' and on the 'Barton Cylinder'. Although the plots are different, there are similarities between the Mesopotamian and Jewish myths.

In the beginning of both myths the universe is shapeless and there is nothing but water. In the beginning of Enûma Eliš there is Abzu (freshwater) and Tiamat (saltwater), which mingle together. In the beginning of Genesis, "darkness was over the surface of the deep" and the "spirit of God" (רוּחַ אֱלֹהִים) is "hovering over the waters".[Genesis 1:2] It has been argued that the Hebrew word for "the deep", tehom, is cognate with tiamat.[2] In the Enûma Eliš there are six generations of gods, created one after the other. Each god is associated with something, such as sky or earth. This parallels the six days of creation in Genesis, where Elohim (plural) creates a different thing on each day.

In the Enûma Eliš, the sixth-generation god Marduk consults with other gods and decides to make mankind as servants, so that the gods can rest. Likewise, Elohim makes mankind on the sixth day (saying "let us make mankind in our image") and then rests.

In both myths, day and night precede the creation of the luminous bodies (Genesis 1:5, 8, 13, and 14ff.; Enûma Eliš 1:38), whose function is to yield light and mark time (Genesis 1:14; Enûma Eliš 5:12–13).

He Fashioned stands for the great gods. As for the stars, he set up constellations corresponding to them. He designated the year and marked out its divisions, Apportioned three stars each to twelve months. When he had made plans of the days of the year… (Enûma Eliš, Tablet 5)

And God said, "Let there be lights in the vault of the sky to separate the day from the night, and let them serve as signs to mark sacred times, and days and years, and let them be lights in the vault of the sky to give light on the earth". And it was so. (Genesis 1:14-15)

The days of the week and their ritual implications from Genesis 1:5-2, 3 can be compared to the Atra-Hasis, which describes the evolution of the weekly calendar as prescribed by the creator god Enki. As in Genesis, the seventh day is seen as the end of the week, which consists of six regular days. For Babylonians the first, seventh and fifteenth of the month were holy days and each month lasted for five seven-day weeks.

The Enûma Eliš portrays Marduk as setting the constellations in place rather than being bound by their movements as had all former gods. The henotheistic idea that one god had control over the movement of the stars, which represented the other gods, appears as a transit to Biblical monotheism.

Cosmography

The cosmography of Genesis is that of the ancient Near East,[3] in which the Earth was thought to be a flat disk floating on water. The flat-disk Earth was seen as one big supercontinent surrounded by a superocean, of which the known seas — what today are called the Mediterranean Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea — were inlets. The Earth, the sea around it, and the air (or sky) above it were thought to be inside a huge hemisphere, and this hemisphere was thought to be surrounded by water. The dome of this hemisphere (the firmament) was thought of as a solid upside-down bowl (made of tin according to the Sumerians, and iron according to the Egyptians) with the stars embedded in it. The fresh-water sea beneath the Earth was the source of all fresh-water springs, rivers, and wells.[3]

In both the Enûma Eliš and Genesis, a god creates this hemisphere (or upside-down bowl) in the midst of the water. In Genesis 1:6 Elohim says "Let there be a vault between the waters to separate water from water" and goes on to create dry land within it. In the Enûma Eliš, Marduk cuts Tiamat in two to make the heavens above and Earth below.

Epic of Gilgamesh and Genesis

The Epic of Gilgamesh is an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia. The earliest poems in the Epic date from the Third Dynasty of Ur (circa 2100 BC). Book XI of the Epic of Gilgamesh contains creation and flood stories that have many elements in common with the Book of Genesis. One of these poems mentions Gilgamesh’s journey to meet the flood hero, as well as a short version of the flood story.[4]

Dating of the tales

Sections dealing with Utnapishtim may date to a later period, as the flood myth appears to originate from a flooding of the Euphrates around 1900 BCE that affected several cities, including Shuruppak, a major setting of the story.[5][6] One possible early source of the creation and flood stories can be found in the Epic of Atra-Hasis, whose tablets have been dated to about 1650 BC.[7]

Failure to gain immortality

In both tales there is a plant that can bestow immortality and a snake that prevents the characters from gaining that immortality.[8]:37 In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh finds a plant that can restore youthfulness, but it is snatched from him by a snake. In Genesis, Yahweh tells Adam and Eve not to eat fruit from the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden, saying that they will die if they do so.[Genesis 3:2-3] However, a snake convinces Adam and Eve to eat from the tree, saying "You will not certainly die ... you will be like God, knowing good and evil".[Genesis 3:4-5] Yahweh then banishes Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, lest they also eat from the Tree of Life and live forever.[Genesis 3:22-23]

In another Mesopotamian tale, a mythical man named Adapa also unknowingly excludes himself from immortality. The tale is first attested in the Kassite period (14th century BC). There are three main parallels between the tales of Adapa and Adam. Both men undergo a test before a god based upon something they were to eat; both fail the test and thus forgo immortality; their failure has consequences for mankind. The god Enki/Ea tells Adapa to go to heaven and apologize to the god Anu, but warns him that he will die if he eats the food in heaven. When Adapa declines Anu's food, Anu tells him that it was not the food of death but of immortality, and sends Adapa back to Earth.[9][10][11] Likewise, in Genesis, Yahweh tells Adam that he will die if he eats from the Tree of Knowledge. When Adam eats from the tree he is cast out of Eden lest he also eat from the Tree of Life and gain immortality.[Genesis 3:22-23]

Loss of innocence

In the beginning both Enkidu and the Eden couple are in harmony with nature. They live naked among the trees and wildlife and have a naive innocence. However, that innocence is lost once each does something that puts him out of harmony with nature.[8]:37

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Shamhat is sent to civilize Enkidu. After they have sex and spend a week alone with each other, the wild animals no longer respond to Enkidu as they did before. Shamhat proclaims that Enkidu has become "wise" and "like a god". She makes clothing for him and introduces him to a human diet. In the last stage of his civilization, Enkidu journeys to the great city of Uruk where new pleasures and experiences await. In Genesis, however, Adam and Eve's loss of innocence is portrayed as something bad. The snake tells Adam and Eve that they will become "like God" if they eat fruit from the Tree of Knowledge. When they do so, they realize that they are naked and hide themselves out of shame.[Genesis 3:7-8] Yahweh then makes clothes for them[Genesis 3:21] and dooms them to a life of hardship (specifically, farming and childbirth) outside the Garden.

Great Flood

The 11th tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh contains the Utnapishtim flood myth and has a number of parallels to the Noah flood myth of Genesis 6–9. According to Alan Millard, "No Babylonian text provides so close a parallel to Genesis as does the flood story of Gilgamesh XI".[12] Michael Coogan mentions the following similarities.[8]:56–57

Both tales begin with a god becoming angry at mankind. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Enlil was disturbed so much by the noise of mankind that he decided to wipe it out with a flood. In Genesis, Yahweh decided to wipe out mankind with a flood because of mankind's "wickedness".[Genesis 6:5-7]

In both tales, a god warns a man of the coming flood so that he and his family can be saved. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the god Ea/Enki disagrees with Enlil's plan and warns a man called Utnapishtim. In Genesis, Yahweh warns Noah because he is "righteous", "blameless" and "walked faithfully with God".[Genesis 6:9]

In both tales, the god tells the man to build a boat, gives specific instructions on how to build it, and tells him to take his family and all kinds of animals on board:

| Epic of Gilgamesh | Genesis |

|---|---|

All the living beings that I had I loaded on it, I had all my kith and kin go up into the boat, all the beasts and animals of the field… (Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet XI) | ...Noah and his sons, Shem, Ham and Japheth, together with his wife and the wives of his three sons, entered the ark. They had with them every wild animal according to its kind... (Genesis 7:13-14)) |

In both tales, when the storm ends, the man releases a dove and a raven to find if dry ground has appeared again:

| Epic of Gilgamesh | Genesis |

|---|---|

I sent out a dove, and let her go. The dove flew hither and thither, but as there was no resting-place for her, she returned. Then I sent out a swallow, and let her go. The swallow flew hither and thither, but as there was no resting-place for her she also returned. Then I sent out a raven, and let her go. The raven flew away and saw the abatement of the waters. She settled down to feed, went away, and returned no more. (Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet XI) | Noah ... sent out a raven, and it kept flying back and forth until the water had dried up from the earth. Then he sent out a dove to see if the water had receded from the surface of the ground. But the dove could find nowhere to perch because there was water over all the surface of the earth; so it returned to Noah in the ark. He waited seven more days and again sent out the dove from the ark. When the dove returned to him in the evening, there in its beak was a freshly plucked olive leaf! Then Noah knew that the water had receded from the earth. He waited seven more days and sent the dove out again, but this time it did not return to him. (Genesis 8:6-12) |

When the flood ends, the boats are sitting on top of a mountain and the man then makes an offering to his god(s):

| Epic of Gilgamesh | Genesis |

|---|---|

To Mount Nisir the ship drifted. On Mount Nisir the boat stuck fast and it did not slip away. [...] Then I let everything go out unto the four winds, and I offered a sacrifice. I poured out a libation upon the peak of the mountain. [...] The gods gathered like flies around the sacrifice. (Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet XI) | ...on the seventeenth day of the seventh month the ark came to rest on the mountains of Ararat [...] Then Noah built an altar to the LORD and, taking some of all the clean animals and clean birds, he sacrificed burnt offerings on it. The LORD smelled the pleasing aroma ... (Genesis 8:4 and Genesis 8:20-21) |

At the end of the Utnapishtim tale, he and his wife are given immortality by the gods and are sent to dwell in a faraway paradise. At the end of the Noah tale, he and his family receive the Covenant of the Rainbow - Yahweh's promise to never again destroy mankind with a flood.[Genesis 9:12-16]

Emesh and Enten, Cain and Abel

Many scholars have pointed to the similarities between the Sumerian tale of Emesh and Enten and the biblical tale of Cain and Abel.[13] Samuel Noah Kramer called the Emesh and Enten tale "the closest extant Sumerian parallel to the Biblical Cain and Abel story".[14] The Emesh and Enten tale is found on clay tablets from the 3rd millennium BCE[15] while the oldest source of the Hebrew Bible is thought to have been written during the 6th century BCE.[16]

In the Sumerian tale, the god Enlil has sex with the Earth, which gives birth to two boys named Emesh and Enten. Emesh is a personification of summer and Enten a personification of winter. Each brother brings an offering to Enlil, but Enten becomes angry with Emesh and the two begin an argument.[17] In Genesis, Adam has sex with Eve, who gives birth to two boys named Cain and Abel. Cain worked the soil and Abel kept flocks. Each brother brings an offering to Yahweh. Yahweh looks favorably on Abel's offering but not on Cain's, so Cain becomes angry.[Genesis 4:1-5]

At this point, however, the similarities end. In the Sumerian tale, Enlil intervenes and declares Enten the winner of the debate. Emesh accepts Enlil's judgment and the brothers reconcile.[17] In Genesis, Cain murders his brother Abel.[Genesis 4:8]

Gods

The ancient Sumerian chief deity was Enlil, the Lord of the Wind. Enlil owed nominal loyalty to his father Anu/Heaven but outside of southern Mesopotamia he gradually became more important, evolving to the status of king of the gods. In Canaan Enlil was known as El, the father of an entire pantheon of gods.

In the Atra-Hasis, the chief of the gods, Enlil (known as Ellil in Akkadian) had been confronted by a revolt of the lesser gods, which caused him to create humans as servants. However, after some centuries pass the humans became a nuisance. Finally, Enlil released a devastating flood to reduce the human population.

In the second verse of Genesis God, who is called Elohim (literally the plural "Gods") in the Hebrew, is said to hover over the waters. This description of God and the use of the name Elohim further reveals this Mesopotamian god’s influence.

Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters. (Genesis 1:2)

This spirit (or "wind", Hebrew ruaḥ) moving over the waters parallels the wind of the storm god Marduk mentioned in the Enûma Eliš,[18] and also compares directly with the mythology of Enlil who was made visible by traces of his passing such as ripples on the water.

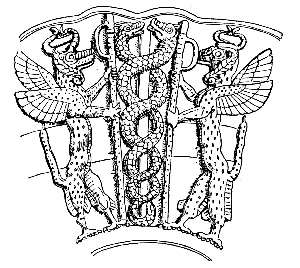

Ningishzida was a Mesopotamian serpent deity associated with the underworld. He was often depicted protectively wrapped around a tree as a guardian. Thorkild Jacobsen interprets his name in Sumerian to mean "lord of the good tree."[19]

Despite apparent similarities between Genesis and the Enûma Eliš, there are also significant differences. The most notable is the absence from Genesis of the "divine combat" (the gods' battle with Tiamat) which secures Marduk's position as king of the world, but even this has an echo in the claims of Yahweh's kingship over creation in such places as Psalm 29 and Psalm 93, where he is pictured as sitting enthroned over the floods and Isaiah 27:1. "In that day, the Lord will punish with his sword; his fierce, great and powerful sword; Leviathan the gliding serpent, Leviathan the coiling serpent; he will slay the monster of the sea." Thus this creation account may be seen as either a borrowing or historicizing of Mesopotamian myth[20] or, in contrast, may be seen as a repudiation of Mesopotamian ideas about origins and humanity.[21]

See also

- Hyperdiffusionism in archaeology

- Mesopotamian religion

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- Christianity and Paganism

- Comparative mythology

- Comparative religion

- Sumerian King Alulim as biblical Adam

References

- 1 2 3

- ↑ Yahuda, A., The Language of the Pentateuch in its Relation to Egyptian (Oxford, 1933)

- 1 2 Seeley 1991, pp. 227–240 and Seeley 1997, pp. 231–55

- ↑ "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature; The death of Gilgameš (three versions, translated)".

- ↑ Schmidt (1931)

- ↑ Martin (1988)pp. 20-23

- ↑ Lambert and Millard, Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood, Oxford, 1969

- 1 2 3 Coogan, Michael D. (2008). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533272-8.

- ↑ Shea, William H. Adam in ancient Mesopotamian traditions. Andrews University.

- ↑ Liverani, Mario. Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography. Cornell University Press, 2007. (Ch1 Adapa, guest of the Gods, pp.21-23)

- ↑ Adapa: Babylonian mythical figure

- ↑ Millard A.R. "A new Babylonian 'Genesis' story," Tyndale Bulletin, 18 (1967) p. 13

- ↑ Autumn Stanley (1995). Mothers and daughters of invention: notes for a revised history of technology. Rutgers University Press. pp. 539–. ISBN 978-0-8135-2197-8. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ Samuel Noah Kramer (1961). Sumerian mythology: a study of spiritual and literary achievement in the third millennium B.C. Forgotten Books. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-1-60506-049-1. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ↑ John H. Walton (30 July 2009). The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate. InterVarsity Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-8308-3704-5. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ↑ Davies, G.I (1998). "Introduction to the Pentateuch". In John Barton. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. p. 37.

- 1 2 "The debate between Winter and Summer" (translation). The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ Hayes, Christine. "Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible) — Lecture 3 — The Hebrew Bible in Its Ancient Near Eastern Setting: Genesis 1-4 in Context". Open Yale Courses. Yale University.

- ↑ Jacobsen, Thorkild The Treasures of Darkness: History of Mesopotamian Religion Yale University Press; New edition (1 July 1978) ISBN 0-300-02291-3 (page 7)

- ↑ Heidel, Alexander Babylonian Genesis Chicago University Press; 2nd edition (1 Sep 1963) ISBN 0-226-32399-4; Smith, Mark S. The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.; 2nd edition (18 Oct 2002) ISBN 0-8028-3972-X; Smith, Mark S. The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts Oxford University Press USA; New Ed edition (27 Nov 2003) ISBN 0-19-516768-6; Frank Moore Cross 'Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel' Harvard University Press; New edition (29 Aug 1997) ISBN 0-674-09176-0]

- ↑ K. A. Mathews, vol. 1A, Genesis 1-11:26, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2001), p. 89.

External links

- The Development, Heyday, and Demise of Panbabylonism by Gary D. Thompson