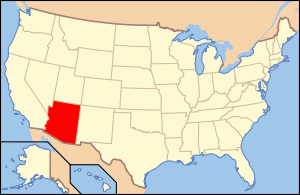

Paleontology in Arizona

Paleontology in Arizona refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Arizona. The fossil record of Arizona dates to the Precambrian. During the Precambrian, Arizona was home to a shallow sea which was home to jellyfish and stromatolite-forming bacteria. This sea was still in place during the Cambrian period of the Paleozoic era and was home to brachiopods and trilobites, however it withdrew during the Ordovician and Silurian. The sea returned during the Devonian and was home to brachiopods, corals, and fishes. Sea levels began to rise and fall during the Carboniferous, leaving most of the state a richly vegetated coastal plain during the low spells. During the Permian, Arizona was richly vegetated but was submerged by seawater late in the period.

During the Triassic, Arizona was home to a rich forest home to dinosaurs and early relatives of mammals. Jurassic Arizona had a drier climate and was covered by sand dunes where dinosaurs left behind footprints. During the Cretaceous, part of eastern portions of the state were covered by the Western Interior Seaway, home to marine reptiles, including plesiosaurs and turtles. Most of Arizona was dry land during the Cenozoic era when the state was inhabited by wildlife including camels, horses, mastodons, and giant ground sloths. Local Native Americans devised myths to explain fossils. By the mid-19th century the state's fossils had already come to the attention of trained scientists. Major local finds include the Petrified Forest, Permian fossil footprints, and fossil pterosaur footprints. The Triassic tree Araucarioxylon arizonicum is the Arizona state fossil.

Prehistory

Arizona was covered by a shallow sea during the Precambrian. Stromatolites formed there.[1] During the Proterozoic interval of Precambrian time, jellyfish lived in Arizona. Their fossils were preserved in what is now the Grand Canyon.[2] Arizona was still covered by a shallow sea during the ensuing Cambrian period of the Paleozoic era. Brachiopods, trilobites and other contemporary marine life of Arizona left behind remains in the western region of the state.[1] The sea withdrew from the state during the Ordovician and Silurian. Although some of the state's Ordovician sedimentary deposits have persisted to the present, all of the state's Silurian rocks have been eroded away. Accordingly, no contemporary fossils are known from the state.[1] Deposition resumed during the Devonian when Arizona was once more submerged by the sea. Contemporary local marine life included brachiopods and corals.[1] In the Devonian period, Arizona was home to primitive fishes.[2] Local sea levels began to periodically rise and fall throughout the ensuing Carboniferous period. During periods of low water levels, much of the state was a coastal plain environment.[1] Plants that grew in Arizona during the Mississippian left behind fossils.[2] Near the end of the ensuing Permian period, Arizona was once more covered by sea water.[1] Later plants from the Permian period did as well.[2] A "great diversity" of plants composed the Permian flora of Arizona. They left fossils in the area now occupied by many of the trails leading down into the Grand Canyon.[3]

With the start of the Mesozoic era, geologic forces elevated the topography of the state's southwestern region.[1] During the Late Triassic, this area was being drained by channels of water flowing toward Pangaea's western coast.[4] At the time of the Dockum Group's deposition, about 220 million years ago, Arizona had a very similar environment to that of nearby Texas.[5] Triassic plant fossils such as clubmosses and ferns were preserved in the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest.[3] During the Triassic, Arizona was home to amphibians that left behind fossils near Meteor Crater.[3] Triassic dicynodonts left behind remains near St. Johns.[3] Arizona is also the best known source of Chindesaurus fossils. Chindesaurus is notable for providing an evolutionary link between the local fauna and the most primitive known dinosaurs such as Eoraptor and Herrerasaurus, which are found in South America.[6] Prosauropods are present but rare in Arizona's Late Triassic deposits.[7] The phytosaurid Rutiodon lived here as well.[8] Fossils attributed to the possible dinosaur Tecovasaurus, known only from teeth, have also been found in the state.[8]

During the Jurassic, much of the state was covered in sand dunes. Local dinosaurs left behind their footprints.[1] Among the larger fauna was the early sauropodomorph dinosaur Sarahsaurus.[9]

Into the Cretaceous, the uplift in western Arizona was forming mountains. Sea water once again intruded into the eastern part of the state. This sea was inhabited by marine reptiles such as turtles and plesiosaurs.[1] On land, the brachiosaurid sauropod Sonorasaurus lived in what is now southern Arizona during the middle part of the Cretaceous.[10]

Most of Arizona was dry land during the Cenozoic era. There were a wide variety of different habitats where wildlife such as camels, horses, and mastodons lived.[1] The Oligocene Mineta Formation of Arizona is one of only seven fossil footprint-bearing stratigraphic units of that age in the western United States.[11] During the Miocene, Arizona was home to camels, which are preserved in what is now Yuma County.[12] During the Pleistocene, the local animal life included camels, mastodons, rodents, and giant sloths. These left behind fossils in what is now Graham County.[3] During the Quaternary, the local climate began to dry and many of the local bodies of water disappeared.[1] At some point in the Pleistocene, mastodons were mired at the San Pedro Valley marsh site, not far from a salt lake. Their skeletons were actually preserved standing upright where they were trapped.[3]

History

Indigenous interpretations

The geology and fossils of Arizona was a possible influence on Zuni creation mythology. Zuni creation stories contain considerable parallels to modern science's understanding of earth's history. The Zunis believed that the modern world was just one in a temporal series of worlds whose inhabitants differed. Similar beliefs are found in other indigenous peoples of the Americas, such as the Aztec. When the earth began, it was wet and dark and subject to cataclysmic earthquakes. The world was populated by weird, frightening monsters. It was peopled by the precursors to modern humans. Zuni mythology describes these early people as incompletely human, having bulging eyes, ears like bats', webbed toes, wet skin and tails and living in caves. They eked out a meager living in caves on an island of mud. The Sun's Twin Children feared that the vulnerable ur-people would be killed by the monsters before they could become "completed" people. So, protected by magic shields, they armed themselves with rainbows and launched arrows made of lightning to kill the monsters. Their lightning arrows sparked huge fires that dried up the water and baked the mud solid, making the world safe for the pre-human people to finish evolving into modern humans. However, now people were menaced by dangerous carnivores such as giant bears and mountain lions. To protect humanity the Twin Heroes traveled the land and destroyed these threats with lightning. Their flesh burnt away and their bones were baked hard like stone.[13]

Scientific research

In 1853 the Pacific Railroad Exploration survey became the first to write about Arizona's petrified forest. In 1873 the Smithsonian sent an expedition through Fort Wingate to the petrified forest to collect samples of the eponymous petrified wood.[2] In 1900 the United States Geological Survey dedicated a report to the local petrified forest. The author expressed deep concern about the future prospects of the fossils because many people were taking specimens both small and large. The report encouraged swift action to preserve the spectacular fossils.[2] In 1906, action was taken to declare Petrified Forest officially a national monument.[2] In 1915, Charles Schuchert made a significant discovery of fossil footprints at the Grand Canyon. Charles W. Gilmore visited the Grand Canyon area during the 1920s to collect specimens of these footprints for the Smithsonian Institution. The Smithsonian was also interested in acquiring Permian-aged footprints, which are abundant in the area.[14] He also wanted to create an exhibit and interpretive center for Paleozoic tracks at Hermit Trail. Gilmore's fruitful research into the area's Paleozoic trace fossils resulted in many publications.[14] In 1938, the fossil cast of a jellyfish was discovered in one of the Grand Canyon's Proterozoic rocks. This was the oldest known jellyfish fossil ever discovered.[2] In 1957 Stokes described the ichnogenus Pteraichnus from the Morrison Formation of Arizona.[15] These tracks were likely left by pterosaurs.[16]

Protected areas

People

Births

- Sterling Nesbitt was born in Mesa on March 25, 1982.

Deaths

- Edwin Harris Colbert died in Flagstaff on 15 November 2001 at age 96.

- Paul S. Martin died in Tucson on September 13, 2010.

Natural history museums

- Arizona Mining and Mineral Museum, Phoenix

- Arizona Museum of Natural History, Mesa

- Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff

- University of Arizona Mineral Museum, Tucson

Events

- Tucson Gem & Mineral Show[17]

See also

- Paleontology in California

- Paleontology in Colorado

- Paleontology in Nevada

- Paleontology in New Mexico

- Paleontology in Utah

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Gillette, Rieboldt, Springer, and Scotchmoor (2010); "Paleontology and geology".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Murray (1974); "Arizona", page 93.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Murray (1974); "Arizona", page 94.

- ↑ Hunt, Santucci, and Kenworthy (2006); "Petrified Forest National Park", page 64.

- ↑ Jacobs (1995); "Chapter 2: The Original Homestead", page 38.

- ↑ Jacobs (1995); "Chapter 2: The Original Homestead", page 39.

- ↑ Jacobs (1995); "Chapter 2: The Original Homestead", page 47.

- 1 2 Fraser, Nicholas C. and Hans-Dieter Sues (1997). In the Shadow of the Dinosaurs: Early Mesozoic Tetrapods Cambridge University Press. p. 233.

- ↑ Timothy B. Rowe, Hans-Dieter Sues and Robert R. Reisz (2011). "Dispersal and diversity in the earliest North American sauropodomorph dinosaurs, with a description of a new taxon". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1708): 1044–1053. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1867. PMC 3049036

. PMID 20926438.

. PMID 20926438. - ↑ Ratkevich, R (1998). "New Cretaceous brachiosaurid dinosaur, Sonorasaurus thompsoni gen et sp. nov, from Arizona". Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science 31: 71-82.

- ↑ Lockley and Hunt (1999); "The Puzzle of Miocene Tracks in the Oligocene", page 260.

- ↑ Murray (1974); "Arizona", page 95.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Zuni Paleontology", page 111.

- 1 2 Lockley and Hunt (1999); "Western Traces in the 'Age of Amphibians'", page 34.

- ↑ Lockley and Hunt (1999); "Figure 4.40", page 160.

- ↑ Lockley and Hunt (1999); "The Real Pterosaur Tracks Story", pages 158-159.

- ↑ Garcia and Miller (1998); "Appendix B: Major Fossil Shows", page 195.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in Arizona. |

- Garcia; Frank A. Garcia, Donald S. Miller (1998). Discovering Fossils. Stackpole Books. p. 212. ISBN 0811728005. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Gillette, David D., Sarah Rieboldt, Dale Springer, Judy Scotchmoor. July 14, 2010. "Arizona, US". The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.

- Hunt, ReBecca K., Vincent L. Santucci and Jason Kenworthy. 2006. "A preliminary inventory of fossil fish from National Park Service units." in S. G. Lucas, J. A. Spielmann, P. M. Hester, J. P. Kenworthy, and V. L. Santucci (eds.), Fossils from Federal Lands. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 34, pp. 63–69.

- Jacobs, L. L., III. 1995. Lone Star Dinosaurs. Texas A&M University Press.

- Lockley, Martin and Hunt, Adrian. Dinosaur Tracks of Western North America. Columbia University Press. 1999.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2005). Fossil Legends Of The First Americans. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11345-6.

- Murray, Marian. 1974. Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. 348 pp.