Ouachita Mountains

The Ouachita Mountains (/ˈwɒʃᵻtɔː/ WOSH-i-taw)[1] are a mountain range in west central Arkansas and southeastern Oklahoma. The range's subterranean roots may extend as far as central Texas, or beyond it to the current location of the Marathon Uplift. Along with the Ozark Mountains, the Ouachita Mountains form the U.S. Interior Highlands, one of the few major mountainous regions between the Rocky Mountains and the Appalachian Mountains.[2][3] The highest peak in the Ouachitas is Mount Magazine in west-central Arkansas which rises to 2,753 feet (839 m).[4]

Etymology

R. Harlan claimed that the word Ouachita is composed of two Choctaw words: ouac, a buffalo, and chito, large. It means the country of large buffaloes, numerous herds of the American bison having formerly covered the prairies of Ouachita.[5]

Historian Muriel H. Wright wrote that the name was probably derived from the Choctaw words owa, meaning hunt and chito, meaning big. She said that ouachita meant a big hunt (i.e., far away from their home).[6]

According to the article "Ouachita Mountains" by Cole and Marston in the Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, the name comes from the French spelling of the Caddo word washita, meaning "good hunting grounds."[4]

Geology and physiography

The Ouachita Mountains are a physiographic section of the larger Ouachita province (which includes both the Ouachita Mountains and the Arkansas Valley), which in turn is part of the larger Interior Highlands physiographic division.[7]

The Ouachita Mountains are fold mountains like the Appalachian Mountains to the east, and were originally part of that range. During the Pennsylvanian period, roughly 300 million years ago, the coastline of the Gulf of Mexico ran through the central parts of Arkansas. The South American Plate drifted northward, riding up over the denser North American continental crust.[8] Geologists call this collision the Ouachita orogeny. The collision buckled the overriding plate, producing the fold mountains we call the Ouachitas. At one time the Ouachita Mountains were very similar in height to the current elevations of the Rocky Mountains. Because of the Ouachitas' age, the craggy tops have eroded away, leaving the low formations that used to be the heart of the mountains.

Unlike most other mountain ranges in the United States, the Ouachitas run east and west rather than north and south. Also, the Ouachitas are distinctive in that volcanism, metamorphism, and intrusions are notably absent throughout most of the system. The Ouachitas tend to be clustered into distinct sub-ranges separated by relatively broad valleys.

The Ouachitas are noted for quartz crystal deposits around the Mount Ida area and for renowned Arkansas novaculite whetstones. This quartz was formed during the Ouachita orogeny, as folded rocks cracked and allowed fluids from deep in the Earth to fill the cracks.

The Ouachita Mountain area of Arkansas is dominated by Cambrian through Pennsylvanian clastic sediments, with the lower Collier formation in the core of the range and the Atoka formation on the flanks. The Atoka Formation, formed in the Pennsylvanian Period, is a sequence of marine, mostly tan to gray silty sandstones and grayish-black shales. Some rare calcareous beds and siliceous shales are known.[9] The Collier sequence is composed of gray to black, lustrous shale containing occasional thin beds of dense, black, and intensely fractured chert. An interval of bluish-gray, dense to spary, thin-bedded limestone may be present. Near its top, the limestone is conglomeratic and pelletoidal, in part, with pebbles and cobbles of limestone, chert, meta-arkose, and quartz. It was formed during the Late Cambrian.[9]

Vertical quartzite and slate strata along the eastern flank of the Ouachitas.

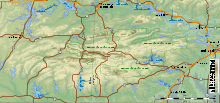

Vertical quartzite and slate strata along the eastern flank of the Ouachitas. Satellite image of the Ouachita Mountains.

Satellite image of the Ouachita Mountains. The South Fourche LaFave River, Ouachita Mountains, Arkansas.

The South Fourche LaFave River, Ouachita Mountains, Arkansas.

Flora

Tree species native to the Ouachita area include northern red, post, black, and white oak, shortleaf and loblolly pine, and mockernut hickory.[4] The mountains are known to contain at least 20 endemic plant species (i.e. plants that occur nowhere else). These include Sabatia arkansana, Valerianella nuttallii, Liatris compacta and Quercus acerifolia.[10]

Subdivisions

The Ouachitas are divided loosely into several sub-ranges which do not always have clearly defined boundaries.

Athens Piedmont – This division contains a series of low peaks and ridges, none more than 1,000 feet (300 m) tall, located to the south of the main Ouachita range. The Athens Piedmont extends from Arkadelphia in the east to approximately the Oklahoma border in the west, and contains the northern half of Clark and Howard counties, and almost all of Pike and Sevier counties in Arkansas, and a small portion of east-central McCurtain County, Oklahoma.

Caddo, Missouri and Cossatot Mountains – These three ranges form a single unified massif which is difficult to divide into sections. The names generally refer to the portion of the mountains in which the headwaters of these three rivers are located. The Caddo Mountains are located on the east, bordering the Crystal Range. The Missouri Mountains are in the center of the range, and the Cossatot Mountains are to the west, bordering the Cross Range. The topography is extremely rugged, and these three ranges contain the highest peaks in the southern Ouachitas, including several that rise well over 2,300 feet (700 m), with the tallest being Raspberry Mountain at 2,367 feet (721 m). Several major rivers of southwest Arkansas rise in this range, including the Cossatot, Saline, Little Missouri, Caddo, Rolling Fork, and also several short headwater streams of the Ouachita River. The area contains several National Forest recreation sites and other amenities because of its extremely scenic nature, and Congress at one time voted to approve it as part of the National Park system, if not for a veto by President Truman.

Cross Range – This division is located in Polk and Sevier counties, Arkansas, and extreme eastern McCurtain County, Oklahoma. The tallest peak is Whiskey Peak, at approximately 1,600 feet (490 m).

Crystal Range – This division is located to the west-southwest of the Zigzag Range, in Montgomery County, Arkansas. It was so named because of the presence of quartz crystals of high quality, which are found here. The mountains of the Crystal Range are generally somewhat taller than the Zigzags.

Fourche Mountains – This division includes the main backbone of the Ouachita system, and extends in a long, almost unbroken ridge from northwestern Saline County just west of Little Rock, Arkansas, all the way into eastern Oklahoma. This continuous ridge often has local names for particularly high spots, including Rich Mountain, the second-highest peak in the Ouachitas after Mount Magazine. The ridge is analogous to the Blue Ridge of the Appalachians. The ridge reaches its highest elevations just east of the Arkansas–Oklahoma border. This ridge also forms a watershed divide between the Arkansas River basin to the north and the Red River basin to the south. The ridge is tall enough to affect climate in western Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma; the land north of the ridge is drier than it would otherwise be, and the land to the south is wetter, due to a rain shadow effect.

Northern Ouachitas – This division includes several disconnected peaks between the Fourche Mountains to the south and the Arkansas River to the north, including Mount Magazine, the highest peak in the Ouachitas. Other notable peaks in this region include Mount Nebo, Cavanal Mountain and the Sans Bois Mountains (Oklahoma), and Sugarloaf Knob (Arkansas and Oklahoma).

Zigzag Range – This division is found in northern Garland County, Arkansas, near Hot Springs National Park. It is so named because of the jagged appearance of the peaks from a distance. Most of the peaks in this range are not exceptionally tall, ranging from approximately 1000 to 1600 feet (300 to 490 m).

Tourism

The Ouachita Mountains contain the Ouachita National Forest, Hot Springs National Park and Lake Ouachita, as well as numerous state parks and scenic byways mostly throughout Arkansas. They also contain the Ouachita National Recreation Trail, a 223-mile-long (359 km) hiking trail through the heart of the mountains. The trail runs from Talimena State Park in Oklahoma to Pinnacle Mountain State Park near Little Rock, Arkansas. It is a well maintained, premier trail for hikers, backpackers, and mountain bikers (for only selected parts of the trail).

The Talimena Scenic Drive begins at Mena, Arkansas, and traverses 54 miles (87 km) of Winding Stair and Rich Mountains, long narrow east-west ridges which extend into Oklahoma. Rich Mountain reaches an elevation of 2,681 feet (817 m) in Arkansas near the Oklahoma border. The 2-lane winding road is similar in routing, construction, and scenery to the Blue Ridge Parkway of the Appalachian Mountains.[11]

History

The mountains were home to the Ouachita tribe, for which they were named. Later French explorers translated the name to its present spelling. The first recorded exploration was in 1541 by Hernando de Soto. Later, in 1804, President Jefferson sent William Dunbar and Dr. George Hunter to the area after the Louisiana Purchase. Hot Springs National Park became one of the nation's first parks in 1832. The Battle of Devil's Backbone was fought here at the ridge of the same name in 1863. In August 1990, the U.S. Forest Service discontinued clearcutting as the primary tool for harvesting and regenerating short leaf, pine and hardwood forests in the Ouachita National Forest.

References

- ↑ "Ouachita Definition". dictionary.com. Random House, Inc. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- ↑ "Managing Upland Forests of the Midsouth". United States Forestry Service. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ↑ "A Tapestry of Time and Terrain: The Union of Two Maps - Geology and Topography". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- 1 2 3 Cole, Shayne R. & Richard A. Marston. "Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. "Ouachita Mountains."". Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ↑ Harlan, R. 1834. "Notice of fossil bones found in the Tertiary formation of the State of Louisiana." Trans. Amer. Philos. Soc. iv pp. 397-403., at Oceans of Kansas.

- ↑ Wright, Muriel H. "Some Geographic Names of French Origin in Oklahoma." Chronicles of Oklahoma. Volume 7, Number 2, pp. 188-193. Accessed March 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Physiographic divisions of the conterminous U. S.". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ↑ Viele, G. W.; Thomas, W. A. (1989). "Tectonic synthesis of the Ouachita orogenic belt". In Hatcher, R. D. Jr.; Thomas, W. A.; Viele, G. W. The Appalachian-Ouachita Orogen in the United States. Geological Society of America. pp. 695–728. ISBN 0-8137-5209-4.

- 1 2 http://www.geology.arkansas.gov/geology/strat_arvalley_ouachitamtn.htm Stratigraphic Summary of the Arkansas Valley and Ouachita Mountains

- ↑ Pringle, J. S.; Witsell, T. (2005). "A new species of Sabatia (Gentianaceae) from Saline County, Arkansas" (PDF). Sida. 21 (3): 1249–1262. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-11. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ http://www.trais.com/tcatalog_trail.aspx?trailid=XFA101-040, accessed 11 Mar 2011

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ouachita Mountains. |

- Geology of the Ouachita Mountains, from a rockhound's perspective.[dead link|date]

- Friends of the Ouachita Trail (FoOT)

- Lakeouachita.org: Lake Ouachita — largest lake in the Ouachita Mountains.

Coordinates: 34°30′01″N 94°30′02″W / 34.50038°N 94.5005°W