Opossum

| Didelphidae[1] Temporal range: Early Miocene–Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Didelphimorphia Gill, 1872 |

| Family: | Didelphidae Gray, 1821 |

| Genera | |

|

Several; see text | |

The opossums, also known as possums, are marsupial mammals of the order Didelphimorphia /daɪˌdɛlfᵻˈmɔːrfiə/). The largest order of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere, it comprises 103 or more species in 19 genera. Opossums originated in South America, and entered North America in the Great American Interchange following the connection of the two continents. Their unspecialized biology, flexible diet, and reproductive habits make them successful colonizers and survivors in diverse locations and conditions.

Etymology

The word "opossum" is borrowed from the Virginia Algonquian (Powhatan) language, and was first recorded between 1607 and 1611 by the Jamestown colonists John Smith (as "opassom") and William Strachey (as "aposoum").[3] The word ultimately derives from the Proto-Algonquian word *wa˙p- aʔθemw, meaning "white dog" or "white beast/animal".

They are also commonly called possums, particularly in the Southern United States and Midwest. Following the arrival of Europeans in Australia, the term "possum" was borrowed to describe distantly related Australian marsupials of the suborder Phalangeriformes,[4] which are more closely related to other Australian marsupials such as kangaroos.

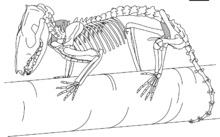

Characteristics

Didelphimorphs are small to medium-sized marsupials, ranging in size from a small mouse to a large house cat. They tend to be semi-arboreal omnivores, although there are many exceptions. Most members of this taxon have long snouts, a narrow braincase, and a prominent sagittal crest. The dental formula is: 5.1.3.44.1.3.4. By mammalian standards, this is an unusually full jaw. The incisors are very small, the canines large, and the molars are tricuspid.

Didelphimorphs have a plantigrade stance (feet flat on the ground) and the hind feet have an opposable digit with no claw. Like some New World monkeys, opossums have prehensile tails. Like all marsupials, the fur consists of awn hair only, and the females have a pouch. The tail and parts of the feet bear scutes. The stomach is simple, with a small cecum.[5] Notably, the male opossum has a forked penis bearing twin glandes.[6][7][5]

Opossums have a remarkably robust immune system, and show partial or total immunity to the venom of rattlesnakes, cottonmouths, and other pit vipers.[8][9] Opossums are about eight times less likely to carry rabies than wild dogs, and about one in eight hundred opossums is infected with this virus.[10]

Although all living opossums are essentially opportunistic omnivores, different species vary in the amount of meat and vegetation they include in their diet. Members of the Caluromyinae are essentially frugivorous; whereas the lutrine opossum and Patagonian opossum primarily feed on other animals.[11] The yapok (Chironectes minimus) is particularly unusual, as it is the only living semi-aquatic marsupial, using its webbed hindlimbs to dive in search of freshwater mollusks and crayfish.[12] Most opossums are scansorial, well-adapted to life in the trees or on the ground, but members of the Caluromyinae and Glironiinae are primarily arboreal, whereas species of Metachirus, Monodelphis, and to a lesser degree Didelphis show adaptations for life on the ground.[13]

Reproduction and life cycle

As a marsupial, the opossum has a reproductive system including a divided uterus and marsupium, which is the pouch.[14] The average estrous cycle of the opossum is about 28 days.[15] Opossums do possess a placenta,[16] but it is short-lived, simple in structure, and, unlike that of placental mammals, is not fully functional.[17] The young are therefore born at a very early stage, although the gestation period is similar to many other small marsupials, at only 12 to 14 days.[18] Once born, the offspring must find their way into the marsupium to hold on to and nurse from a teat.

Female opossums often give birth to very large numbers of young, most of which fail to attach to a teat, although as many as thirteen young can attach,[19] and therefore survive, depending on species. The young are weaned between 70 and 125 days, when they detach from the teat and leave the pouch. The opossum lifespan is unusually short for a mammal of its size, usually only two to four years. Senescence is rapid.[20]

The species are moderately sexually dimorphic with males usually being slightly larger, much heavier, and having larger canines than females.[19] The largest difference between the opossum and non-marsupial mammals is the bifurcated penis of the male and bifurcated vagina of the female (the source of the term "didelphimorph," from the Greek "didelphys," meaning double-wombed).[21] Opossum spermatozoa exhibit sperm-pairing, forming conjugate pairs in the epididymis. This may ensure that flagella movement can be accurately coordinated for maximal motility. Conjugate pairs dissociate into separate spermatozoa before fertilization.[22]

Behavior

Opossums are usually solitary and nomadic, staying in one area as long as food and water are easily available. Some families will group together in ready-made burrows or even under houses. Though they will temporarily occupy abandoned burrows, they do not dig or put much effort into building their own. As nocturnal animals, they favor dark, secure areas. These areas may be below ground or above.

When threatened or harmed, they will "play possum", mimicking the appearance and smell of a sick or dead animal. This physiological response is involuntary (like fainting), rather than a conscious act. In the case of baby opossums, however, the brain does not always react this way at the appropriate moment, and therefore they often fail to "play dead" when threatened. When an opossum is "playing possum", the animal's lips are drawn back, the teeth are bared, saliva foams around the mouth, the eyes close or half-close, and a foul-smelling fluid is secreted from the anal glands. The stiff, curled form can be prodded, turned over, and even carried away without reaction. The animal will typically regain consciousness after a period of a few minutes to 4 hours, a process that begins with slight twitching of the ears.[23]

Adult opossums do not hang from trees by their tails, as sometimes depicted, though babies may dangle temporarily. Their semi-prehensile tails are not strong enough to support a mature adult's weight. Instead, the opossum uses its tail as a brace and a fifth limb when climbing. The tail is occasionally used as a grip to carry bunches of leaves or bedding materials to the nest. A mother will sometimes carry her young upon her back, where they will cling tightly even when she is climbing or running.

Threatened opossums (especially males) will growl deeply, raising their pitch as the threat becomes more urgent. Males make a clicking "smack" noise out of the side of their mouths as they wander in search of a mate, and females will sometimes repeat the sound in return. When separated or distressed, baby opossums will make a sneezing noise to signal their mother. If threatened, the baby will open its mouth and quietly hiss until the threat is gone.

Biochemistry

Opossums are remarkably resistant to snake venom, ricin, and botulinum toxin.[9]

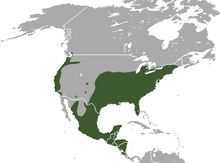

Habitat

Opossums are found in the Americas.

Hunting and foodways

The Virginia opossum was once widely hunted and consumed in the United States.[24][25][26][27] Sweet potatoes were eaten together with the possum in America's southern area.[28][29] South Carolina cuisine includes opossum eating.[30] Jimmy Carter killed opossums[31][32] in addition to other small game.[33][34] Raccoon, opossum, partridges, prairie hen, and frogs were among the fare Mark Twain recorded as part of American cuisine.[35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45]

Opossum farms have been operated in the United States.[46][47][48]

In Dominica, Grenada, Trinidad and St. Lucia the common opossum or manicou is popular and can only be hunted during certain times of the year owing to overhunting. The meat is traditionally prepared by smoking, then stewing. It is light and fine-grained, but the musk glands must be removed as part of preparation. The meat can be used in place of rabbit and chicken in recipes. Historically, hunters in the Caribbean would place a barrel with fresh or rotten fruit to attract opossums that would feed on the fruit or insects.

In northern/central Mexico, opossums are known as "tlacuache" or "tlacuatzin". Their tails are eaten as a folk remedy to improve fertility.[49] In the Yucatán peninsula they are known in the Yucatec Mayan language as "och"[50] and they are not considered part of the regular diet by Mayan people, but still considered edible in times of famine.

Opossum oil (possum grease) is high in essential fatty acids and has been used as a chest rub and a carrier for arthritis remedies given as topical salves.

Opossum pelts have long been part of the fur trade.

Classification

Classification based on Voss and Jansa (2009)[51]

- Family Didelphidae

- Subfamily Glironiinae

- Genus Glironia

- Bushy-tailed opossum (Glironia venusta)

- Genus Glironia

- Subfamily Caluromyinae

- Genus Caluromys

- Subgenus Caluromys

- Bare-tailed woolly opossum (Caluromys philander)

- Subgenus Mallodelphys

- Derby's woolly opossum (Caluromys derbianus)

- Brown-eared woolly opossum (Caluromys lanatus)

- Subgenus Caluromys

- Genus Caluromysiops

- Black-shouldered opossum (Caluromysiops irrupta)

- Genus Caluromys

- Subfamily Hyladelphinae

- Genus Hyladelphys

- Kalinowski's mouse opossum (Hyladelphys kalinowskii)

- Genus Hyladelphys

- Subfamily Didelphinae

- Tribe Didelphini

- Genus Metachirus

- Brown four-eyed opossum (Metachirus nudicaudatus)

- Genus Chironectes

- Yapok or water opossum (Chironectes minimus)

- Genus Metachirus

- Unnamed subgroup

- Unnamed subgroup

- Genus Didelphis

- White-eared opossum (Didelphis albiventris)

- Big-eared opossum (Didelphis aurita)

- Guianan white-eared opossum (Didelphis imperfecta)

- Common opossum (Didelphis marsupialis)

- Andean white-eared opossum (Didelphis pernigra)

- †Didelphis solimoensis[55]

- Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana)

- Genus Philander

- Anderson's four-eyed opossum (Philander andersoni)

- Deltaic four-eyed opossum (Philander deltae)

- Southeastern four-eyed opossum (Philander frenatus)

- McIlhenny's four-eyed opossum (Philander mcilhennyi)

- Mondolfi's four-eyed opossum (Philander mondolfii)

- Olrog's four-eyed opossum (Philander olrogi)

- Gray four-eyed opossum (Philander opossum)

- †Genus Thylophorops

- Genus Didelphis

- Tribe Marmosini

- Genus Marmosa

- Subgenus Marmosa

- Heavy-browed mouse opossum (Marmosa andersoni)

- Isthmian mouse opossum (Marmosa isthmica)

- Rufous mouse opossum (Marmosa lepida)

- Mexican mouse opossum (Marmosa mexicana)

- Linnaeus's mouse opossum (Marmosa murina)

- Quechuan mouse opossum (Marmosa quichua)

- Robinson's mouse opossum (Marmosa robinsoni)

- Red mouse opossum (Marmosa rubra)

- Marmosa simonsi

- Tyleria mouse opossum (Marmosa tyleriana)

- Marmosa waterhousei

- Guajira mouse opossum (Marmosa xerophila)

- Marmosa zeledoni

- Subgenus Micoureus

- Alston's mouse opossum (Marmosa alstoni)

- White-bellied woolly mouse opossum (Marmosa constantiae)

- Woolly mouse opossum (Marmosa demerarae)

- †Marmosa laventica[57]

- Tate's woolly mouse opossum (Marmosa paraguayanus)

- Little woolly mouse opossum (Marmosa phaeus)

- Bare-tailed woolly mouse opossum (Marmosa regina)

- Subgenus Marmosa

- Genus Monodelphis (es:Monodelphis translation of Spanish article)

Monodelphis domestica

Monodelphis domestica- Sepia short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis adusta)

- Northern three-striped opossum (Monodelphis americana)

- Monodelphis arlindoi[58]

- Northern red-sided opossum (Monodelphis brevicaudata)

- Yellow-sided opossum (Monodelphis dimidiata)

- Gray short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica)

- Emilia's short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis emiliae)

- Amazonian red-sided opossum (Monodelphis glirina)

- Handley's short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis handleyi)[59]

- Ihering's three-striped opossum (Monodelphis iheringi)

- Pygmy short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis kunsi)

- Marajó short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis maraxina)

- Osgood's short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis osgoodi)

- Hooded red-sided opossum (Monodelphis palliolata)

- Reig's opossum (Monodelphis reigi)

- Ronald's opossum (Monodelphis ronaldi)

- Chestnut-striped opossum (Monodelphis rubida)

- Monodelphis sanctaerosae[60]

- Long-nosed short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis scalops)

- Southern red-sided opossum (Monodelphis sorex)

- Southern three-striped opossum (Monodelphis theresa)

- Monodelphis touan[58]

- Red three-striped opossum (Monodelphis umbristriata)

- One-striped opossum (Monodelphis unistriata)

- Genus Tlacuatzin (es:Tlacuatzin translation of Spanish article)

- Grayish mouse opossum (Tlacuatzin canescens)

- Genus Marmosa

- Tribe Thylamyini

- Genus Chacodelphys

- Chacoan pygmy opossum (Chacodelphys formosa)

- Genus Cryptonanus

- Agricola's gracile opossum (Cryptonanus agricolai)

- Chacoan gracile opossum (Cryptonanus chacoensis)

- Guahiba gracile opossum (Cryptonanus guahybae)

- Red-bellied gracile opossum (Cryptonanus ignitus) † 1962

- Unduavi gracile opossum (Cryptonanus unduaviensis)

- Genus Gracilinanus

- Aceramarca gracile opossum (Gracilinanus aceramarcae)

- Agile gracile opossum (Gracilinanus agilis)

- Wood sprite gracile opossum (Gracilinanus dryas)

- Emilia's gracile opossum (Gracilinanus emilae)

- Northern gracile opossum (Gracilinanus marica)

- Brazilian gracile opossum (Gracilinanus microtarsus)

- Genus Lestodelphys

- Patagonian opossum (Lestodelphys halli)

- Genus Marmosops

- Bishop's slender opossum (Marmosops bishopi)

- Narrow-headed slender opossum (Marmosops cracens)

- Creighton's slender opossum Marmosops creightoni

- Dorothy's slender opossum (Marmosops dorothea)

- Dusky slender opossum (Marmosops fuscatus)

- Handley's slender opossum (Marmosops handleyi)

- Tschudi's slender opossum (Marmosops impavidus)

- Gray slender opossum (Marmosops incanus)

- Panama slender opossum (Marmosops invictus)

- Junin slender opossum (Marmosops juninensis)

- Neblina slender opossum (Marmosops neblina)

- White-bellied slender opossum (Marmosops noctivagus)

- Delicate slender opossum (Marmosops parvidens)

- Brazilian slender opossum (Marmosops paulensis)

- Pinheiro's slender opossum (Marmosops pinheiroi)

- Genus Thylamys

- †Thylamys colombianus[57]

- Cinderella fat-tailed mouse opossum (Thylamys cinderella)

- Thylamys citellus[61]

- Elegant fat-tailed mouse opossum (Thylamys elegans)

- Thylamys fenestrae[62]

- Karimi's fat-tailed mouse opossum (Thylamys karimii)

- Paraguayan fat-tailed mouse opossum (Thylamys macrurus)

- †Thylamys minutus[57]

- White-bellied fat-tailed mouse opossum (Thylamys pallidior)

- Thylamys pulchellus[63]

- †Thylamys pinei[64]

- Common fat-tailed mouse opossum (Thylamys pusillus)

- Argentine fat-tailed mouse opossum (Thylamys sponsorius)

- Tate's fat-tailed mouse opossum (Thylamys tatei)

- Dwarf fat-tailed mouse opossum (Thylamys velutinus)

- Buff-bellied fat-tailed mouse opossum (Thylamys venustus)

- †Thylamys zettii[65]

- †Genus Zygolestes

- †Zygolestes tatei

- Genus Chacodelphys

- Tribe Didelphini

- Subfamily Glironiinae

References

- ↑ Gardner, A. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Francisco Goin; Alejandra Abello; Eduardo Bellosi; Richard Kay; Richard Madden; Alfredo Carlini (2007). "Los Metatheria sudamericanos de comienzos del Neógeno (Mioceno Temprano, Edad-mamífero Colhuehuapense). Parte I: Introducción, Didelphimorphia y Sparassodonta". Ameghiniana. 44 (1): 29–71.

- ↑ Mithun, Marianne (2001). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge University Press. p. 332. ISBN 0-521-29875-X.

- ↑ "possum". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- 1 2 Krause, William J.; Krause, Winifred A. (2006).The Opossum: Its Amazing Story. Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri. p. 39

- ↑ Martinelli, P. M., and J. C. Nogueira. "Penis morphology as a distinctive character of the murine opossum group (Marsupialia Didelphidae): a preliminary report." Mammalia 61.2 (1997): 161-166.

- ↑ Barros, Michelle Andrade, et al. "Marsupial morphology of reproduction: South America opossum male model." Microscopy research and technique 76.4 (2013): 388-397.

- ↑ "The Opossum: Our Marvelous Marsupial, The Social Loner". Wildlife Rescue League.

- 1 2 Lipps, B. V. (1999). "Anti-Lethal Factor from Opossum Serum is a Potent Antidote for Animal, Plant and Bacterial Toxins". Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins. 5. doi:10.1590/S0104-79301999000100005.

- ↑ Cantor SB, Clover RD, Thompson RF (1994). "A decision-analytic approach to postexposure rabies prophylaxis". Am J Public Health. 84 (7): 1144–8. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.7.1144. PMC 1614738

. PMID 8017541.

. PMID 8017541. - ↑ Vieira, Emerson R.; De Moraes, D. Astua (2003). "Carnivory and insectivory in Neotropical marsupials". Predators with Pouches: the biology of carnivorous marsupials. Csiro Publishing. pp. 267–280. ISBN 0-643-06634-9.

- ↑ Marshall, Larry G. (1978). "Chironectes minimus". Mammalian Species. 109 (99): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3504051. JSTOR 3504051.

- ↑ Flores, David A. (2009). "Phylogenetic analysis of postcranial skeletal morphology in didelphid marsupials". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 320: 1–81. doi:10.1206/320.1.

- ↑ Campbell, N. & Reece, J. (2005)BiologyPearson Education Inc.

- ↑ Reproduction – Life Cycle. Retrieved 2014-4-9.

- ↑ Enders, A.C. & Enders, R.K. (2005). "The placenta of the four-eyed opossum (Philander opossum))". The Anatomical Record. 165 (3): 431–439. doi:10.1002/ar.1091650311.

- ↑ Krause, W.J. & Cutts, H. (1985). "Placentation in the Opossum, Didelphis virginiana". Acta Anatomica. 123 (3): 156–171. doi:10.1159/000146058. PMID 4061035.

- ↑ O'Connell, Margaret A. (1984). Macdonald, D., ed. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 830–837. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- 1 2 North American Mammals: Didelphis virginiana. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ Opossum Facts. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ "Possum Hunt".

- ↑ Moore, H.D. (1996). "Gamete biology of the new world marsupial, the grey short-tailed opossum, monodelphis domestica". Reproduction, fertility, and development. 8 (4): 605–15. doi:10.1071/RD9960605.

- ↑ Found an Orphaned or injured Opossum?. Opossumsocietyus.org. Retrieved on 2012-05-03.

- ↑ Sutton, Keith (January 12, 2009) Possum days gone. ESPN Outdoors.

- ↑ Wild Game Recipes online. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ Powell, Bonnie Azab (2006-10-14) The joy of the ‘Joy of Cooking,’ circa 1962. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ Apicius (7 May 2012). Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome. Courier Corporation. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-0-486-15649-1.

- ↑ Jones, Evan (2007). American Food: The Gastronomic Story. Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-58567-904-1.

- ↑ "Possum Recipes". 11 November 1999.

- ↑ "Cooking a Possum". 9 November 1999.

- ↑ Jimmy Carter (1995). Always a Reckoning, and Other Poems. Times Books. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-0-8129-2434-3.

- ↑ Elizabeth Raum (13 September 2011). Gift of Peace: The Jimmy Carter Story: The Jimmy Carter Story. Zonderkidz. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-0-310-72757-6.

- ↑ "President Jimmy Carter Inducted into Georgia Hunting and Fishing Hall of Fame".

- ↑ "Carter Shares Times".

- ↑ Mark Twain; Charles Dudley Warner (1904). The Writings of Mark Twain [pseud.].: A tramp abroad. Harper & Bros. pp. 263–.

- ↑ "Mark Twain's Rapturous List of His Favorite American Foods". 2 March 2012.

- ↑ "A little bill of fare".

- ↑ Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1907). The Writings of Mark Twain [pseud.]. Harper. pp. 263–.

- ↑ Charles Dudley Warner (1907). The Writings of Mark Twain [pseud.]: A tramp abroad. Harper & brothers. pp. 263–.

- ↑ Mark Twain (27 October 2010). Mark Twain's Library of Humor. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 200–. ISBN 978-0-307-76542-0.

- ↑ Mark Twain (1901). A tramp abroad. American Publishing Company. pp. 263–.

- ↑ Mark Twain (18 October 2004). Mark Twain's Helpful Hints for Good Living: A Handbook for the Damned Human Race. University of California Press. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-0-520-93134-3.

- ↑ William Dean Howells (1888). Mark Twain's Library of Humor. Charles L. Webster & Company. pp. 232–.

- ↑ DiGregorio, Sarah (6 July 2010). "Mark Twain Eats America".

- ↑ Helen Walker Linsenmeyer; Bruce Kraig (2 December 2011). Cooking Plain, Illinois Country Style. SIU Press. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-0-8093-3074-4.

- ↑ "The Evening Independent – Google News Archive Search".

- ↑ "The Hour – Google News Archive Search".

- ↑ "Crossville Chronicle".

- ↑ "::: BIBLIOTECA :::".

- ↑ Worley, Paul M. (10 October 2013). "Telling and Being Told: Storytelling and Cultural Control in Contemporary Yucatec Maya Literatures". University of Arizona Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ Voss, Robert S.; Sharon A. Jansa (2009). "Phylogenetic relationships and classification of didelphid marsupials, an extant radiation of New World metatherian mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 322: 1–177. doi:10.1206/322.1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Goin, Francisco J.; Ulyses F. J. Pardinas (1996). "Revision de las especies del genero Hyperdidelphys Ameghino, 1904 (Mammalia, Marsupialia, Didelphidae. Su significacion filogenetica, estratigrafica y adaptativa en el Neogeno del Cono Sur sudamericano". Estudios Geologicos. 52 (5–6): 327–359. doi:10.3989/egeol.96525-6275.

- ↑ Goin, Francisco J.; Martin de los Reyes (2011). "Contribution to the knowledge of living representatives of the genus Lutreolina Thomas, 1910 (Mammalia, Marsupialia, Didelphidae)". Historia Natural. 1 (2): 15–25. JSTOR 20627135.

- ↑ Martínez-Lanfranco, Juan A.; Flores, David; Jayat, J. Pablo; d'Elía, Guillermo (2014). "A new species of lutrine opossum, genus Lutreolina Thomas (Didelphidae), from the South American Yungas". Journal of Mammalogy. 95 (2): 225. doi:10.1644/13-MAMM-A-246.

- ↑ Cozzuol, Mario A.; Francisco J. Goin; Martin de los Reyes; Alceu Ranzi (2006). "The oldest species of Didelphis (Mammalia, Marsupialia, Didelphidae) from the late Miocene of Amazonia". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (4): 663–667. doi:10.1644/05-MAMM-A-282R2.1.

- ↑ Goin, Francisco J.; Natalia Zimicz; Martin de los Reyes; Leopoldo Soibelzon (2009). "A new large didelphid of the genus Thylophorops (Mammalia: Didelphimorphia: Didelphidae), from the late Tertiary of the Pampean Region (Argentina)". Zootaxa. 2005: 35–46.

- 1 2 3 Goin, Francisco J. (1997). "New clues for understanding Neogene marsupial radiations". Vertebrate Paleontology of the Miocene in Colombia. A History of the Neotropical Fauna. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. pp. 185–204. ISBN 1-56098-418-X.

- 1 2 Pavan, Silvia Eliza; Rossi, Rogerio Vieira; Schneider, Horacio (2012). "Species diversity in the Monodelphis brevicaudata complex (Didelphimorphia: Didelphidae) inferred from molecular and morphological data, with the description of a new species". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 165: 190. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00791.x.

- ↑ Flores, D. & Solari, S. 2011. Monodelphis handleyi. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2.

- ↑ Voss, Robert S.; Pine, Ronald H.; Solari, Sergio (2012). "A New Species of the Didelphid Marsupial Genus Monodelphis from Eastern Bolivia". American Museum Novitates. 3740 (3740): 1. doi:10.1206/3740.2.

- ↑ Flores, D. & Teta, P. 2011. Thylamys citellus. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2.

- ↑ Flores, D. & Martin, G.M. 2011. Thylamys fenestrae. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2.

- ↑ Flores, D. & Martin, G.M. 2011. Thylamys pulchellus. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2.

- ↑ Goin, Francisco J.; C.I. Montalvo, G. Visconti (2000). "Los marsupiales (Mammalia) del Mioceno Superior de la Formacion Cerro Azul (Provincia de La Pampa, Argentina)". Estudios Geologicos. 56: 101–126. doi:10.3989/egeol.00561-2158.

- ↑ Goin, Francisco J. (1997). "Thylamys zettii, nueva especie de marmosino (Marsupialia, Didelphidae) del Cenozoico tardio de la region Pampeana". Ameghiniana. 34 (4): 481–484.

External links

- Possums or Opossums? on Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- View the monDom5 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser.

| Wikispecies has information related to: Didelphidae |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Didelphis virginiana. |