Operation Pegasus

| Operation Pegasus | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Arnhem | |

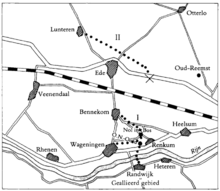

Map of Pegasus I and II | |

| Type | Evacuation |

| Location | Lower Rhine at Renkum, the Netherlands |

| Planned by | Lt Colonel David Dobie Major Digby Tatham-Warter , Dutch resistance |

| Objective | Safely evacuate survivors of the British 1st Airborne Division |

| Date | Night of 22/23 October 1944 2100 – 0200 |

| Executed by | Royal Canadian Engineers 506 PIR, 101st Airborne Division Dutch resistance |

| Outcome | 138 men evacuated |

| Casualties | 1 man (missing) |

Operation Pegasus was a military operation carried out on the Lower Rhine near the village of Renkum, close to Arnhem in the Netherlands. Overnight on 22–23 October 1944, the Allies successfully evacuated a large group of men trapped in German occupied territory who had been in hiding since the Battle of Arnhem.

The fighting north of the Rhine in September had forced the 1st British Airborne division to withdraw, leaving several thousand men behind. Several hundred of these were able to evade capture and go into hiding, usually with the assistance of the Dutch Resistance. Initially the men hoped to be able to wait for the British 2nd Army to resume their advance and thus relieve them, but when it became clear that the Allies would not cross the Rhine that year the men decided to escape back to Allied territory. The first escape operation was a great success and over 100 men were able to return to their own lines, but a second operation was compromised and failed. Despite this the resistance continued to help the evaders and many more men were able to escape in small groups over the winter.

Background

Battle of Arnhem

In September 1944 the Western Allies launched Operation Market Garden, an attempt by the British 2nd Army to bypass the Siegfried Line and advance into the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland. The operation required the First Allied Airborne Army to seize several bridges over rivers and canals in the Netherlands, allowing ground forces to advance and cross the Lower Rhine at Arnhem.

The 1st British Airborne Division dropped onto Arnhem on 17 September. They encountered far greater resistance than had been expected and only a small force were able to reach Arnhem road bridge. XXX Corps ground advance became delayed and without reinforcement this small force under Lt Colonel John Frost was overwhelmed. The rest of the division became trapped in a small perimeter in Oosterbeek and were withdrawn on the night of 25–26 September in Operation Berlin.

Evaders

The figures of men involved in the battle are imprecise but it is believed well over 10,400 men fought north of the Lower Rhine. In Operation Berlin, between 2,400-2,500 men safely withdrew to the south bank, leaving some 7,900 men behind.[1][2] Of these almost 1,500 were killed, 6,000 were in German hands and up to 500 were in hiding in the woods and villages near the river.[1]

Major Digby Tatham-Warter had escaped a German hospital as early as 21 September and having lain low for a week was contacted by the Dutch Resistance who requested his assistance in Ede.[3] In early October he was joined by Brigadier Gerald Lathbury and soon a ‘Brigade HQ in hiding’ was set up.[4] Tatham-Warter made contact with Lieutenant Gilbert Kirschen of the Belgian SAS who arranged supply drops of weapons, uniforms and supplies for the growing number of British hiding in the area.[3]

Piet Kruijff, head of the local Resistance, had been organising the evaders into safe houses in Ede. Soon there were over 80 men in the town and it was becoming so congested that he began housing men in Reemst as well. By the time of the evacuation there were an additional 40 men here.[3] At first it was hoped that the Allied offensive would be quickly resumed thus liberating the men - Tatham-Warter even made plans to carry out operations against the Germans when the 2nd Army began crossing the Rhine.[3] But in October Kirschen informed the Resistance that there were no plans to attack north of the Lower Rhine in the near future. As the presence of so many Allied evaders would place a great strain on the Resistance and expose the civilians hiding them to great risk, it was decided to evacuate the men as soon as possible.[5]

The ‘HQ in hiding’ was in contact with 2nd Army’s escape organisation based in Nijmegen, and when Lt Colonel David Dobie, (commander of 1st Battalion), successfully swam the Rhine on the night of 16 October and reached Allied lines, he was able to make further arrangements.[4] Dobie contacted the XXX Corps and the 101st Airborne Division who approved of the evacuation.[3] He was also able to make contact with Tatham-Warter by telephone and together they drew up a plan that would hopefully allow all of the men in hiding to escape.[3]

Dobie was able to suggest a suitable location on the river near Renkum to make the crossing (codenamed Digby).[3] An RV and route to the river from the north were decided upon, and it was arranged that the men would be met on the north bank by Royal Canadian Engineers & British Royal Engineers of the British XXX Corps escorted by men of the 506 PIR, 101st Airborne Division.[3] To help guide the evaders the crossing point would be marked by tracer fire from a Bofors Gun.[3] The American forces made patrols north of the river and tracer fire was sent over the bank for several nights to disguise the actual purpose of the operation when it came. The date was set for the night of 23–24 October.[6]

Operation

On 20 October the Germans ordered residents of nearby villages to leave their homes by the 22nd. Deciding to take advantage of the confusion this would cause, the operation was thus brought forward to the night of 22–23 October.[6] The men were brought together from their various hides to an RV in the woods north of the river. The German presence in this area was very heavy after the Arnhem fighting and the men assembled in a location only 500 metres from German machine gun nests.[6]

By dark 139 men had assembled. They were mainly from the 1st Airborne Division, but there was also a US 82nd Airborne Division trooper, a number of aircrew, some Dutch civilians and some Russians wishing to join the Allies. The men were organised into platoons and at 9pm began moving south towards the river.[7] Tatham-Warter recorded that the Germans were almost certainly aware of their presence, but perhaps unsure of their numbers and wary of American patrols they kept some distance. There was one ‘contact’ with a patrol and a brief exchange of fire, but no-one was hurt.[3]

At midnight the group reached the riverbank and moved to the crossing point indicated by the Bofors tracer fire. Once there they flashed a V for Victory signal with their torches,[8] but there was an anxious wait of twenty minutes for the boats.[3] In fact, on the south bank Dobie, the engineers and a patrol of E Company, 506 PIR observed the signal and immediately launched their boats, but the British were some 500-800m upriver of the crossing point. Upon reaching the north bank E Company established a small perimeter while men headed east to locate the evaders.[9][10] The men quickly moved downstream and in the next 90 minutes all of them were evacuated,[10] with the exception of a Russian who was caught and arrested by the Germans.[11] The Germans opened fire sporadically and some mortar rounds fell near the crossing, but the fire was inaccurate.[3] Once on the other side the escapees were led to a farmhouse for refreshments, before being driven to Nijmegen where Dobie had arranged a party and champagne.[12] The men were later flown back to the UK, rejoining the men who had escaped in Operation Berlin.

Operation Pegasus II

| Operation Pegasus II | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Arnhem | |

| Type | Evacuation |

| Location | Lower Rhine at Oosterbeek, the Netherlands |

| Objective | Safely withdraw escapees north of the Lower Rhine |

| Date | Night of 18 November 1944 |

| Outcome | Failure |

The success of the first evacuation prompted the Allies to arrange a second attempt. Unfortunately the security of this operation was compromised early, when a reporter impersonated an intelligence officer and interviewed several escapees from the first operation. The subsequent news story alerted the Germans who strengthened their patrols along the river.[13]

Major Hugh Maguire (of HQ, 1st Airborne Division) was put in charge of the second escape[12] The operation largely replicated the original, but was due to take place 4 km further east on the evening of 18 November.[12][13] A party of between 130 and 160 men would attempt to cross the river on this occasion, although this number included a much higher proportion of civilians, aircrew and other non-infantry who were unused to this sort of operation.[12][14] Because of the distance from Ede to the crossing point and the need to skirt a German 'no mans zone', the main party's march to the river was approximately 23 km (compared to the 5 km of Pegasus I) and would take two days to make.[12][15] The main party became fragmented on the second night [15] and whilst attempting to make a short cut one party under Major John Coke of the King's Own Scottish Borderers inevitably stumbled into a German patrol.[12][13] Several men were killed in the resulting firefight - perhaps more than twenty[16] and the evaders were forced to scatter. No-one was able to cross that night, although seven men crossed during the next two days.[12] The Germans searched the area intensively with patrols and spotter planes, enabling them to capture more of the evaders,[12] and most of the Resistance's Dutch guides were killed or captured.[17]

Later escapes

Colonel Graeme Warrack and Captain Alexander Lipmann Kessel had been on the abortive Pegasus II, but were able to escape capture. Like many of the remaining evaders they continued to hide in German occupied territory for some months.[17] In February they joined Brigadier John Hackett, who by now had recovered well from his injuries sustained at Arnhem.[18] Kessel had saved his life during the battle and even performed minor operations during their time in hiding.[19] They eventually escaped across the Waal at Groot-Ammers, 25 miles west of Arnhem on a route later used by another 37 men, including Gilbert Kirschen.[20]

Notable escapees

Although many men had failed to return after the Battle of Arnhem, many were able to escape in Operation Pegasus or with the aid of the resistance over the winter. They included senior ranks:

- Brigadier Gerald Lathbury, CO 1st Parachute Brigade (Operation Pegasus).

- Brigadier John Hackett, CO 4th Parachute Brigade (February 1945).

- Colonel Graeme Warrack, Senior medical officer, 1 Airborne Division (February 1945).

- Lieutenant Colonel David Dobie, CO 1 Battalion, Parachute Regiment (in advance of Operation Pegasus).

- Lieutenant Colonel Martin Herford, 163 RAMC (October 1944).

- Major Allison Digby Tatham-Warter, OC A Company, 2 Battalion, Parachute Regiment (Operation Pegasus).

- Major Anthony Deane-Drummond, 2IC Divisional Signals (Operation Pegasus).

- Major Tony Hibbert, Brigade Major 1st Parachute Brigade (Operation Pegasus).

- Captain Alexander Lipmann Kessel, 16th (Parachute) Field Ambulance (February 1945).

In popular culture

Operation Pegasus was depicted in the 5th episode of the 2001 HBO miniseries Band of Brothers.

References

- 1 2 Waddy, p166

- ↑ Middlebrook, p439

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Digby Tatham-Warter

- 1 2 Waddy, p181

- ↑ Waddy, p180

- 1 2 3 Waddy, p184

- ↑ Waddy, p186

- ↑ Ambrose, p158

- ↑ Ambrose, p159

- 1 2 Waddy, p187

- ↑ Van der Zee, p 135

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Waddy, p188

- 1 2 3 Middlebrook, p438

- ↑ Van der Zee, p136

- 1 2 Van der Zee, p137

- ↑ Pitchfork, p114

- 1 2 Van der Zee, p138

- ↑ Van der Zee, p140

- ↑ Van der Zee, p141

- ↑ Van der Zee, p144

Bibliography

- Ambrose, Stephen (1992). Band of Brothers. Pocket Books & Design. ISBN 0-7434-2990-7.

- Digby Tatham-Warter, Major Allison; Dobie, Lt Colonel David. "Evasion Report: 21st September - 23rd October 1944". Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- Middlebrook, Martin (1994). Arnhem 1944: The Airborne Battle. Viking. ISBN 0-670-83546-3.

- Pitchfork, Graham (2003). Shot Down and On The Run. PRO Publications. ISBN 1-903365-53-8.

- Van der Zee, Henri (1998). The Hunger Winter: Occupied Holland 1944-1945. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9618-5.

- Waddy, John (1999). A Tour of the Arnhem Battlefields. Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 0-85052-571-3.

- Haverhoek, Cees (2008). Get 'm Out /Pegasus I en II. C. Haverhoek. ISBN 978-90-79774-01-2.

- A Bridge Too Far: The Canadian Role in the Evacuation of the British 1st Airborne Division from Arnhem-Oosterbeek, September 1944

Further reading

- Digby Tatham-Warter, Allison (1991). Dutch Courage and 'Pegasus': A Memoir. Self Published.

Coordinates: 51°58′36″N 5°43′31″E / 51.9767°N 5.7252°E