Oedipus complex

In psychoanalysis, the Oedipus complex (or, less commonly, Oedipal complex) is a child's desire, that the mind keeps in the unconscious via dynamic repression, to have sexual relations with the parent of the opposite sex (i.e. males attracted to their mothers, and females attracted to their fathers).[1][2]

The Oedipus complex occurs in the third—phallic stage (ages 3–6)—of the five psychosexual development stages: (i) the oral, (ii) the anal, (iii) the phallic, (iv) the latent, and (v) the genital—in which the source of libidinal pleasure is in a different erogenous zone of the infant's body. The Oedipal complex originally refers to the sexual desire of a son for his mother and does not have to be reciprocated.

Sigmund Freud, who coined the term "Oedipus complex", believed that the Oedipus complex is a desire for the parent in both males and females; he deprecated the term "Electra complex", which was introduced by Carl Gustav Jung in regard to the Oedipus complex manifested in young girls. Freud further proposed that boys and girls experience the complex differently: boys in a form of castration anxiety, girls in a form of penis envy; and that unsuccessful resolution of the complex might lead to neurosis, pedophilia, and homosexuality. A child's identification with the same-sex parent is the successful resolution of the complex.

Men and women who are fixated in the Oedipal and Electra stages of their psychosexual development might be considered "mother-fixated" and "father-fixated." In adult life, this can lead to a choice of a sexual partner who resembles one's parent.

Background

Oedipus refers to a 5th-century BC Greek mythological character Oedipus, who unwittingly kills his father, Laius, and marries his mother, Jocasta. A play based on the myth, Oedipus Rex, was written by Sophocles, ca. 429 BC.

Modern productions of Sophocles' play were staged in Paris and Vienna in the 19th century and were phenomenally successful in the 1880s and 1890s. The Austrian psychiatrist, Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), attended. In his book The Interpretation of Dreams first published in 1899, he proposed that an Oedipal desire is a universal, psychological phenomenon innate (phylogenetic) to human beings, and the cause of much unconscious guilt. He based this on his analysis of his feelings attending the play, his anecdotal observations of neurotic or normal children, and on the fact that Oedipus Rex was effective on both ancient and modern audiences. (He also claimed the play Hamlet “has its roots in the same soil as Oedipus Rex,” and that the differences between the two plays are revealing. “In [Oedipus Rex] the child’s wishful fantasy that underlies it is brought into the open and realized as it would be in a dream. In Hamlet it remains repressed; and—just as in the case of a neurosis—we only learn of its existence from its inhibiting consequences.”)[4][5]

However, in The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud makes it clear that the “primordial urges and fears” that are his concern and the basis of the Oedipal complex are inherent in the myths the play by Sophocles is based on, not primarily in the play itself, which Freud refers to as a “further modification of the legend” that originates in a “misconceived secondary revision of the material, which has sought to exploit it for theological purposes.”[6][7][8]

Freud described the character Oedipus:

His destiny moves us only because it might have been ours — because the Oracle laid the same curse upon us before our birth as upon him. It is the fate of all of us, perhaps, to direct our first sexual impulse towards our mother and our first hatred and our first murderous wish against our father. Our dreams convince us that this is so.[9]

A six-stage chronology of Sigmund Freud's theoretic evolution of the Oedipus complex is:

- Stage 1. 1897–1909. After his father's death in 1896, and having seen the play Oedipus Rex, by Sophocles, Freud begins using the term "Oedipus". As Freud wrote in a 1897 letter, "I found in myself a constant love for my mother, and jealousy of my father. I now consider this to be a universal event in early childhood."

- Stage 2. 1909–1914. Proposes that Oedipal desire is the "nuclear complex" of all neuroses; first usage of "Oedipus complex" in 1910.

- Stage 3. 1914–1918. Considers paternal and maternal incest.

- Stage 4. 1919–1926. Complete Oedipus complex; identification and bisexuality are conceptually evident in later works.

- Stage 5. 1926–1931. Applies the Oedipal theory to religion and custom.

- Stage 6. 1931–1938. Investigates the "feminine Oedipus attitude" and "negative Oedipus complex"; later the "Electra complex".[10]

The Oedipus complex

In classical psychoanalytic theory, the Oedipus complex occurs during the phallic stage of psychosexual development (age 3–6 years), when also occurs the formation of the libido and the ego; yet it might manifest itself at an earlier age.[2][11]

In the phallic stage, a boy's decisive psychosexual experience is the Oedipus complex—his son–father competition for possession of mother. It is in this third stage of psychosexual development that the child's genitalia are his or her primary erogenous zone; thus, when children become aware of their bodies, the bodies of other children, and the bodies of their parents, they gratify physical curiosity by undressing and exploring themselves, each other, and their genitals, so learning the anatomic differences between "male" and "female" and the gender differences between "boy" and "girl".

Psychosexual infantilism—Despite mother being the parent who primarily gratifies the child's desires, the child begins forming a discrete sexual identity—"boy", "girl"—that alters the dynamics of the parent and child relationship; the parents become objects of infantile libidinal energy. The boy directs his libido (sexual desire) upon his mother, and directs jealousy and emotional rivalry against his father—because it is he who sleeps with his mother. Moreover, to facilitate union with mother, the boy's id wants to kill father (as did Oedipus), but the pragmatic ego, based upon the reality principle, knows that the father is the stronger of the two males competing to possess the one female. Nonetheless, the boy remains ambivalent about his father's place in the family, which is manifested as fear of castration by the physically greater father; the fear is an irrational, subconscious manifestation of the infantile id.[12]

Psycho-logic defense—In both sexes, defense mechanisms provide transitory resolutions of the conflict between the drives of the id and the drives of the ego. The first defense mechanism is repression, the blocking of memories, emotional impulses, and ideas from the conscious mind; yet its action does not resolve the id–ego conflict. The second defense mechanism is identification, in which the boy or girl child adapts by incorporating, to his or her (super)ego, the personality characteristics of the same-sex parent. As a result of this, the boy diminishes his castration anxiety, because his likeness to father protects him from father's wrath in their maternal rivalry. In the case of the girl, this facilitates identifying with mother, who understands that, in being females, neither of them possesses a penis, and thus are not antagonists.[13]

Dénouement—Unresolved son–father competition for the psycho-sexual possession of the mother might result in a phallic stage fixation that leads to the boy becoming an aggressive, over-ambitious, and vain man. Therefore, the satisfactory parental handling and resolution of the Oedipus complex are most important in developing the male infantile super-ego. This is because, by identifying with a parent, the boy internalizes Morality; thereby, he chooses to comply with societal rules, rather than reflexively complying in fear of punishment.

Oedipal case study

In Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-year-old Boy (1909), the case study of the equinophobic boy "Little Hans", Freud showed that the relation between Hans's fears—of horses and of his father—derived from external factors, the birth of a sister, and internal factors, the desire of the infantile id to replace father as companion to mother, and guilt for enjoying the masturbation normal to a boy of his age. Moreover, his admitting to wanting to procreate with mother was considered proof of the boy's sexual attraction to the opposite-sex parent; he was a heterosexual male. Yet, the boy Hans was unable to relate fearing horses to fearing his father. As the treating psychoanalyst, Freud noted that "Hans had to be told many things that he could not say himself" and that "he had to be presented with thoughts, which he had, so far, shown no signs of possessing".[14]

Feminine Oedipus attitude

Initially, Freud equally applied the Oedipus complex to the psychosexual development of boys and girls, but later modified the female aspects of the theory as "feminine Oedipus attitude" and "negative Oedipus complex";[15] yet, it was his student–collaborator Carl Jung, who, in 1913, proposed the Electra complex to describe a girl's daughter–mother competition for psychosexual possession of the father.[16]

In the phallic stage, a girl's Electra complex is her decisive psychodynamic experience in forming a discrete sexual identity (ego). Whereas a boy develops castration anxiety, a girl develops penis envy rooted in anatomic fact: without a penis, she cannot sexually possess mother, as the infantile id demands. Resultantly, the girl redirects her desire for sexual union upon father, thus progressing to heterosexual femininity, which culminates in bearing a child, who replaces the absent penis.[17] Furthermore, after the phallic stage, the girl's psychosexual development includes transferring her primary erogenous zone from the infantile clitoris to the adult vagina.

Freud thus considered a girl's negative Oedipus complex to be more emotionally intense than that of a boy, resulting, potentially, in a woman of submissive, insecure personality;[18] thus might an unresolved Electra complex, daughter–mother competition for psychosexual possession of father, lead to a phallic-stage fixation conducive to a girl becoming a woman who continually strives to dominate men (viz. penis envy), either as an unusually seductive woman (high self-esteem) or as an unusually submissive woman (low self-esteem). Therefore, the satisfactory parental handling and resolution of the Electra complex are most important in developing the female infantile super-ego, because, by identifying with a parent, the girl internalizes morality; thereby, she chooses to comply with societal rules, rather than reflexively complying in fear of punishment.

In regards to narcissism

In regards to narcissism, the Oedipus complex is viewed as the pinnacle of the individual's maturational striving for success or for love.[19] In The Economic Problem of Masochism (1924), Freud writes that in “the Oedipus complex… [the parent’s] personal significance for the superego recedes into the background’ and ‘the images they leave behind… link [to] the influences of teachers and authorities…”. Educators and mentors are put in the ego ideal of the individual and they strive to take on their knowledge, skills, or insights.

In Some Reflections on Schoolboy Psychology (1914), Freud writes:

- "We can now understand our relation to our schoolmasters. These men, not all of whom were in fact fathers themselves, became our substitute fathers. That was why, even though they were still quite young, they struck us as so mature and so unattainably adult. We transferred on to them the respect and expectations attaching to the omniscient father of our childhood, and we then began to treat them as we treated our fathers at home. We confronted them with the ambivalence that we had acquired in our own families and with its help we struggled with them as we had been in the habit of struggling with our fathers…"

The Oedipus complex, in narcissistic terms, represents that an individual can lose the ability to take a parental-substitute into his ego ideal without ambivalence. Once the individual has ambivalent relations with parental-substitutes, he will enter into the triangulating castration complex. In the castration complex the individual becomes rivalrous with parental-substitutes and this will be the point of regression. In Psycho-analytic notes on an autobiographical account of a case of paranoia (Dementia paranoides) (1911), Freud writes that “disappointment over a woman” (object drives) or “a mishap in social relations with other men” (ego drives) is the cause of regression or symptom formation. Triangulation can take place with a romantic rival, for a woman, or with a work rival, for the reputation of being more potent.[20]

Freudian theoretic revision

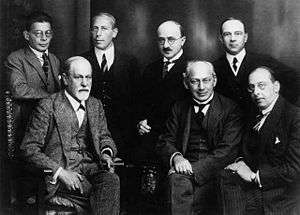

When Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) proposed that the Oedipus complex was psychologically universal, he provoked the evolution of Freudian psychology and the psychoanalytic treatment method, by collaborators and competitors alike.

Carl Gustav Jung

In countering Freud's proposal that the psychosexual development of boys and girls is equal, that each initially experiences sexual desire (libido) for mother, and aggression towards father, student–collaborator Carl Jung counter-proposed that girls experienced desire for father and aggression towards mother via the Electra complex—derived from the 5th-century BC Greek mythologic character Electra, who plotted matricidal revenge with Orestes, her brother, against Clytemnestra, their mother, and Aegisthus, their stepfather, for their murder of Agamemnon, her father, (cf. Electra, by Sophocles).[21][22][23] Moreover, because it is native to Freudian psychology, orthodox Jungian psychology uses the term "Oedipus complex" only to denote a boy's psychosexual development.

Otto Rank

In classical Freudian psychology the super-ego, "the heir to the Oedipus complex", is formed as the infant boy internalizes the familial rules of his father. In contrast, in the early 1920s, using the term "pre-Oedipal", Otto Rank proposed that a boy's powerful mother was the source of the super-ego, in the course of normal psychosexual development. Rank's theoretic conflict with Freud excluded him from the Freudian inner circle; nonetheless, he later developed the psychodynamic Object relations theory in 1925.

Melanie Klein

Whereas Freud proposed that father (the paternal phallus) was central to infantile and adult psychosexual development, Melanie Klein concentrated upon the early maternal relationship, proposing that Oedipal manifestations are perceptible in the first year of life, the oral stage. Her proposal was part of the Controversial discussions (1942–44) at the British Psychoanalytical Association. The Kleinian psychologists proposed that "underlying the Oedipus complex, as Freud described it [...] there is an earlier layer of more primitive relationships with the Oedipal couple".[24] Moreover, Klein's work lessened the central role of the Oedipus complex, with the concept of the depressive position.[25][26]

Wilfred Bion

"For the post–Kleinian Bion, the myth of Oedipus concerns investigatory curiosity—the quest for knowledge—rather than sexual difference; the other main character in the Oedipal drama becomes Tiresias (the false hypothesis erected against anxiety about a new theory)".[27] Resultantly, "Bion regarded the central crime of Oedipus as his insistence on knowing the truth at all costs".[28]

Jacques Lacan

From the postmodern perspective, Jacques Lacan argued against removing the Oedipus complex from the center of psychosexual developmental experience. He considered "the Oedipus complex—in so far as we continue to recognize it as covering the whole field of our experience with its signification [...] [that] superimposes the kingdom of culture" upon the person, marking his or her introduction to symbolic order.[29]

Thus "a child learns what power independent of itself is as it goes through the Oedipus complex [...] encountering the existence of a symbolic system independent of itself".[30] Moreover, Lacan's proposal that "the ternary relation of the Oedipus complex" liberates the "prisoner of the dual relationship" of the son–mother relationship proved useful to later psychoanalysts;[31] thus, for Bollas, the "achievement" of the Oedipus complex is that the "child comes to understand something about the oddity of possessing one's own mind [...] discovers the multiplicity of points of view".[32] Likewise, for Ronald Britton, "if the link between the parents perceived in love and hate can be tolerated in the child's mind [...] this provides us with a capacity for seeing us in interaction with others, and [...] for reflecting on ourselves, whilst being ourselves".[33] As such, in The Dove that Returns, the Dove that Vanishes (2000), Michael Parsons proposed that such a perspective permits viewing "the Oedipus complex as a life-long developmental challenge [...] [with] new kinds of Oedipal configurations that belong to later life".[34]

In 1920, Sigmund Freud wrote that "with the progress of psychoanalytic studies the importance of the Oedipus complex has become, more and more, clearly evident; its recognition has become the shibboleth that distinguishes the adherents of psychoanalysis from its opponents";[35] thereby it remained a theoretic cornerstone of psychoanalysis until about 1930, when psychoanalysts began investigating the pre-Oedipal son–mother relationship within the theory of psychosexual development.[36][37] Janet Malcolm reports that by the late 20th century, to the object relations psychology "avant-garde, the events of the Oedipal period are pallid and inconsequential, in comparison with the cliff-hanging psychodramas of infancy. [...] For Kohut, as for Winnicott and Balint, the Oedipus complex is an irrelevance in the treatment of severe pathology".[38] Nonetheless, ego psychology continued to maintain that "the Oedipal period—roughly three-and-a-half to six years—is like Lorenz standing in front of the chick, it is the most formative, significant, moulding experience of human life [...] If you take a person's adult life—his love, his work, his hobbies, his ambitions—they all point back to the Oedipus complex".[39]

Criticism

In his 1927 book Sex and Repression in Savage Society, anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski demonstrated that the Oedipus complex is not universal.

Some contemporary psychoanalysts agree with the idea of the Oedipus complex to varying degrees; Hans Keller proposed it is so "at least in Western societies";[40] and others consider that ethnologists already have established its temporal and geographic universality.[41] Nonetheless, few psychoanalysts disagree that the "child then entered an Oedipal phase [...] [which] involved an acute awareness of a complicated triangle involving mother, father, and child" and that "both positive and negative Oedipal themes are typically observable in development".[42] Despite evidence of parent–child conflict, the evolutionary psychologists Martin Daly and Margo Wilson note that it is not for sexual possession of the opposite sex-parent; thus, in Homicide (1988), they proposed that the Oedipus complex yields few testable predictions, because they found no evidence of the Oedipus complex in people.[43]

In No More Silly Love Songs: A Realist's Guide to Romance (2010), Anouchka Grose says that "a large number of people, these days believe that Freud's Oedipus complex is defunct [...] 'disproven', or simply found unnecessary, sometime in the last century".[44] Moreover, from the post-modern perspective, Grose contends that "the Oedipus complex isn't really like that. It's more a way of explaining how human beings are socialised [...] learning to deal with disappointment".[44] The elementary understanding being that "You have to stop trying to be everything for your primary carer, and get on with being something for the rest of the world".[45] Nonetheless, the open question remains whether or not such a post-Lacanian interpretation "stretches the Oedipus complex to a point where it almost doesn't look like Freud's any more".[44]

Parent-child and sibling-sibling incestuous unions are almost universally forbidden.[46] An explanation for this incest taboo is that rather than instinctual sexual desire, there is instinctual sexual aversion against these unions (See Westermarck effect). Steven Pinker wrote that "The idea that boys want to sleep with their mothers strikes most men as the silliest thing they have ever heard. Obviously, it did not seem so to Freud, who wrote that as a boy he once had an erotic reaction to watching his mother dressing. But Freud had a wet-nurse, and may not have experienced the early intimacy that would have tipped off his perceptual system that Mrs. Freud was his mother."

In Esquisse pour une autoanalyse, Pierre Bourdieu argues that the success of the concept of Oedipus is inseparable from the prestige associated with ancient Greek culture and the relations of domination that are reinforced in the use of this myth. In other words, if Oedipus was Bantu or Baoule, he probably would not have benefited from the coronation of universality. This remark reminds historically and socially situated character of myth founder of psychoanalysis.[47]

According to Didier Eribon, the book Anti-Oedipus by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari is "a critique of psychoanalytic normativity and Oedipus (...)" and "(...) a setting oedipinianisme devastating issue of (...) ".[48] Eribon considers the Oedipus complex of Freudian or Lacanian psychoanalysis is an "implausible ideological construct" which is an "inferiorization process of homosexuality".[49]

According to Armand Chatard, Freudian representation of the Oedipus complex is little or not supported by empirical data (he relies on Kagan, 1964, Bussey and Bandura, 1999)[50]

See also

References

| Library resources about Oedipus complex |

- ↑ Charles Rycroft A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis (London, 2nd Ed. 1995)

- 1 2 Joseph Childers, Gary Hentzi eds. Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995)

- ↑ Peter Gay (1995) Freud: A Life for Our Time

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. Basic Books. 978-0465019779 (2010) page 282.

- ↑ Oedipus as Evidence: The Theatrical Background to Freud's Oedipus Complex by Richard Armstrong, 1999

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. Basic Books. 978-0465019779 (2010) page 247

- ↑ Fagles, Robert, “Introduction”. Sophocles. The Three Theban Plays. Penguin Classics (1984) ISBN 978-0140444254. page 132

- ↑ Dodds, E. R. “On Misunderstanding the Oedipus Rex”. The Ancient Concept of Progress. Oxford Press. (1973) ISBN 978-0198143772. page 70

- ↑ Sigmund Freud The Interpretation of Dreams Chapter V "The Material and Sources of Dreams" (New York: Avon Books) p. 296.

- ↑ Bennett Simon, Rachel B. Blass "The development of vicissitudes of Freud's ideas on the Oedipus complex" in The Cambridge Companion to Freud (University of California Press 1991) p.000

- ↑ Charles Rycroft A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis (London, 2nd ed., 1995)

- ↑ Allan Bullock, Stephen Trombley The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (London:Harper Collins 1999) pp. 607, 705

- ↑ Allan Bullock, Stephen Trombley The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (London:Harper Collins 1999) pp. 205, 107

- ↑ Frank Cioffi (2005) "Sigmund Freud" entry The Oxford Guide to Philosophy Oxford University Press:New York pp. 323–324

- ↑ Freud, Sigmund (1956). On Sexuality. Penguin Books Ltd.

- ↑ "Freud, Sigmund (1856-1939)". credoreference.com. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ Appignanesisi & Forrester (1992)

- ↑ Allan Bullock, Stephen Trombley The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought Harper Collins:London (1999) pp. 259, 705

- ↑ Pederson, Trevor (2015). The Economics of Libido: Psychic Bisexuality, the Superego, and the Centrality of the Oedipus Complex. karnac.

- ↑ Pederson, Trevor (2015). Superego, and the Centrality of the Oedipus Complex. Karnac.

- ↑ Murphy, Bruce (1996). Benét's Reader's Encyclopedia Fourth edition, HarperCollins Publishers:New York p. 310

- ↑ Bell, Robert E. (1991) Women of Classical Mythology: A Biographical Dictionary Oxford University Press:California pp.177–78

- ↑ Hornblower, S., Spawforth, A. (1998) The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization pp. 254–55

- ↑ Richard Appignanesi ed. Introducing Melanie Klein (Cambridge 2006) p. 173

- ↑ Charles Rycroft A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis (London, 2nd Edn, 1995)

- ↑ Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995)

- ↑ Mary Jacobus, The Poetics of Psychoanalysis (London 2005) p. 259

- ↑ Michael Parsons The Dove that Returns, the Dove that Vanishes (London 2000) p. 45

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, Ecrits: A Selection (London 1997) p. 66

- ↑ Ian Parker, Japan in Analysis (Basingstoke 2008) pp. 82–83

- ↑ Jacques Lacan, Ecrits pp. 218, 182

- ↑ Adam Phillips On Flirtation (London 1994) p. 159

- ↑ Ivan Wood On a Darkling Plain: Journey into the Unconscious (Cambridge 2002) "Ronald Britton" entry p. 118

- ↑ Michael Parsons The Dove that Returns, the Dove that Vanishes (London 2000) p. 4

- ↑ Freud, Sexuality pp. 149-50nn

- ↑ Charles Rycroft A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis (London, 2nd Ed., 1995)

- ↑ Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995) p. 119

- ↑ Janet Malcolm, Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession (London 1988) pp. 35, 136

- ↑ Janet Malcolm, Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession (London 1988), "Aaron Green", pp. 158–59

- ↑ Hans Keller: 1975: 1984 Minus 9 (London, 1975)

- ↑ Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel and Bela Grunberger Freud or Reich?: Psychoanalysis and Illusion (London, 1986).

- ↑ Glen O. Gabbard Long-Term Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (London 2010) p. 11

- ↑ Martin Daly, Margo Wilson Homicide (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1988).

- 1 2 3 Anouchka Grose No More Silly Love Songs (London, 2010) p. 123

- ↑ Anouchka Grose No More Silly Love Songs (London, 2010) p. 124

- ↑ The Tapestry of Culture An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, Ninth Edition, Abraham Rosman, Paula G. Rubel, Maxine Weisgrau, 2009, AltaMira Press, page 101

- ↑ Pierre Bourdieu, "Esquisse pour une auto-analyse", raisons d'agir, 2004

- ↑ Didier Eribon, "Échapper à la psychanalyse", Éditions Léo Scheer, 2005, p.14

- ↑ Didier Eribon, Réflexions sur la question gay, Paris, Fayard, 1999. (ISBN 2213600988), p.129

- ↑ Chatard, Armand (September 2004). "La construction sociale du genre" (PDF). Diversité. 138: 23–30.