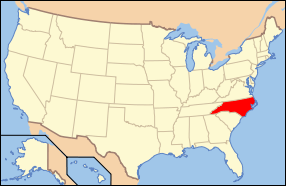

North Carolina in the American Civil War

| State of North Carolina | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Raleigh | ||||||||

| Largest city | Wilmington | ||||||||

| Admission to Confederacy | May 21, 1861 (8th) | ||||||||

| Population | 992,622 Total * 661,563 free * 331,059 slave | ||||||||

| Forces supplied | 155,000 Total * soldiers * sailors * marines | ||||||||

| Casualties | |||||||||

| Major garrisons/armories | |||||||||

| Governor | Henry Clark (1861–1862) Zebulon Vance (1862–1865) | ||||||||

| Lieutenant Governor | None | ||||||||

| Senators | George Davis (1862–1864) Edwin Reade (1864) William Graham (1864–1865) William Dortch (1862–1865) | ||||||||

| Representatives | List | ||||||||

| Restored to the Union | July 4, 1868 | ||||||||

| History of North Carolina |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Confederate States in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Border states |

| Dual governments |

| Territories |

The state of North Carolina provided an important source of soldiers, supplies, and war materiel to the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. The city of Wilmington was one of the leading ports of the Confederacy, providing a vital lifeline of trade with the United Kingdom and other countries, especially after the Union blockade choked off most other Confederate ports. Large supplies of weapons, ammunition, accoutrements, and military supplies flowed from Wilmington throughout the South.

Troops from North Carolina played a major role in dozens of major battles, including the Battle of Gettysburg, where Tar Heels were prominent in Pickett's Charge. One of the last remaining major Confederate armies, that of Joseph E. Johnston, surrendered near Bennett Place in North Carolina after the Carolinas Campaign.

Early war years

North Carolina was a picture of contrasts. In the Coastal Plain, it was a plantation state with a long history of slavery. However, there were no plantations and few slaves in the mountainous western part of the state. These differing perspectives show in the fraught election of 1860 and its aftermath. North Carolina's electoral votes went to Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge, an adamant supporter of slavery who hoped to extend the "peculiar institution" to the United States' western territories, rather than to the Constitutional Union candidate, John Bell, who carried much of the upper South. Yet North Carolina (in marked contrast to most of the states that Breckinridge carried) was reluctant to secede from the Union when it became clear that Republican Abraham Lincoln had won the presidential election. In fact, North Carolina did not secede until May 20, 1861, after the fall of Fort Sumter and the secession of the Upper South's bellwether, Virginia.

Some white North Carolinians, especially yeoman farmers who owned few or no slaves, felt ambivalently about the Confederacy; draft-dodging, desertion, and tax evasion were common during the Civil War years, especially in the Union-friendly western part of the state. Central and Eastern white North Carolinians were more enthusiastic about the Confederate cause; North Carolina contributed more troops to the Confederacy than any other state.[1]

Initially, the policy of the Confederate populace was to embargo cotton shipments to Europe in hope of forcing them to recognize the Confederacy's independence to resume trade. The plan failed, and furthermore the Union's naval blockade of Southern ports drastically shrunk North Carolina's international commerce via shipping. Internally, the Confederacy had far fewer railroads than the Union. The breakdown of the Confederate transportation system took a heavy toll on North Carolina residents, as did the runaway inflation of the war years and food shortages in the cities. In the spring of 1863, there were food riots in Salisbury.[2]

Although there was little military combat in the Western districts, the psychological tensions grew greater and greater. Historians John C. Inscoe and Gordon B. McKinney argue that in the western mountains:

- Differing ideologies turned into opposing loyalties, and those divisions eventually proved as disruptive as anything imposed by outside armies....As the mountains came to serve as refuges and hiding places for deserters, draft dodgers, escaped slaves, and escaped prisoners of war, the conflict became even more localized and internalized, and at the same time became far messier, less rational, and more mean-spirited, vindictive, and personal.[3]

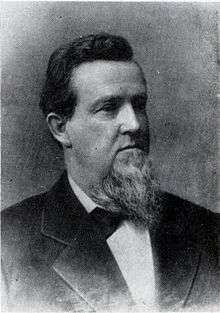

Politics

Henry Toole Clark served as the state's governor from July 1861 to September 1862. Clark founded a Confederate prison in North Carolina, set up European purchasing connections, and built a successful gunpowder mill. His successor Zebulon Vance further increased state assistance for the soldiers in the field. As the war went on, William Woods Holden became a quiet critic of the Confederate government, and a leader of the North Carolina peace movement. In 1864, he was the unsuccessful "peace candidate" against incumbent Governor Vance.[4]

Unionism

Unionists in North Carolina formed a group called the "Heroes of America" that was allied with the U.S. Numbering nearly 10,000 men, a few of them possibly black, they helped Unionists escape to U.S. lines.[5]

Military campaigns in North Carolina

From September 1861 until July 1862, Union Major General Ambrose Burnside, commander of the Department of North Carolina, formed the North Carolina Expeditionary Corps and set about capturing key ports and cities. His successes at Battle of Roanoke Island and Battle of New Bern helped cement Federal control of a part of coastal Carolina.

Fighting continued in North Carolina sporadically throughout the war, particularly along the coast, where the Union army launched several attempts to seize Fort Fisher. In the war's closing days, a large Federal force under General Sherman marched into North Carolina, and in a series of movements that became known as the Carolinas Campaign, occupied much of the state and defeated the Confederates in several key battles, including Averasborough and Bentonville. Unlike the wanton destruction Sherman's troops wrought upon Georgia and South Carolina, they proceeded into North Carolina with a modicum of restraint, as the state had not been especially eager to join the Confederacy. The surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston's Confederate army at Bennett Place in April 1865 essentially ended the war in the Eastern Theater.

Notable Civil War leaders from North Carolina

-

General

Braxton Bragg -

Lt. Gen.

Leonidas Polk -

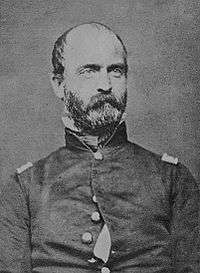

Maj. Gen.

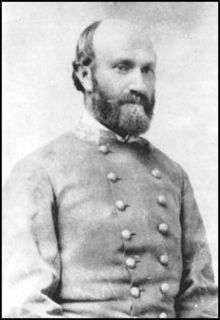

D. H. Hill -

Maj. Gen.

Robert F. Hoke -

Maj. Gen.

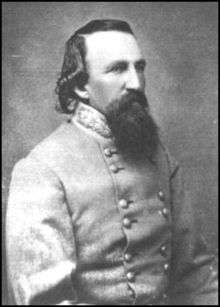

Dorsey Pender -

Maj. Gen.

Stephen Dodson Ramseur -

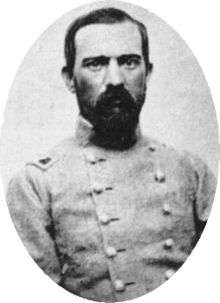

Brig. Gen.

George B. Anderson -

Brig. Gen.

Lewis A. Armistead -

Brig. Gen.

Rufus Barringer -

Brig. Gen.

Laurence S. Baker -

Brig. Gen.

Lawrence O. Branch -

Brig. Gen.

Thomas Lanier Clingman -

Brig. Gen.

William Ruffin Cox -

Brig. Gen.

Junius Daniel -

Brig. Gen.

James B. Gordon -

Brig. Gen.

Bryan Grimes -

Brig. Gen.

Robert D. Johnston -

Brig. Gen.

William W. Kirkland -

Brig. Gen.

James H. Lane -

Brig. Gen.

James Green Martin -

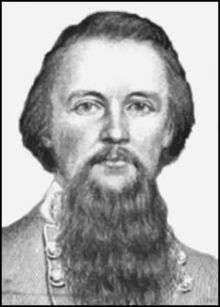

Brig. Gen.

J. Johnston Pettigrew -

Brig. Gen.

Matt W. Ransom -

Brig. Gen.

Alfred M. Scales

Battles of North Carolina

- Battle of Albemarle Sound

- Battle of Averasborough

- Battle of Bentonville

- Battle of Fort Anderson

- Battle of Fort Fisher I

- Battle of Fort Fisher II

- Siege of Fort Macon

- Battle of Goldsboro Bridge

- Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries

- Battle of Kinston

- Battle of Monroe's Cross Roads

- Battle of Morrisville

- Battle of New Bern

- Battle of Plymouth

- Battle of Roanoke Island

- Battle of South Mills

- Battle of Tranter's Creek

- Battle of Washington

- Battle of White Hall

- Battle of Wilmington

- Battle of Wyse Fork

See also

- Confederate States of America - animated map of state secession and confederacy

- List of North Carolina Confederate Civil War units

- List of North Carolina Union Civil War regiments

- North Carolina Monument

- Wilmington, North Carolina, in the Civil War

- Silent Sam statue by John A. Wilson (sculptor)

References

- ↑ John C. Inscoe and Gordon B. McKinney (2003). The Heart of Confederate Appalachia: Western North Carolina in the Civil War. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 9.

- ↑ Brooks D. Simpson (2013). The Civil War: The Third Year Told by Those Who Lived It: (Library of America #234). Library of America. p. 193.

- ↑ John C. Inscoe and Gordon B. McKinney (2003). The Heart of Confederate Appalachia: Western North Carolina in the Civil War. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 9.

- ↑ R. Matthew Poteat (2009). Henry Toole Clark: Civil War Governor of North Carolina. McFarland. pp. 90–118.

- ↑ Foner, Eric (March 1989). "The South's Inner Civil War: The more fiercely the Confederacy fought for its independence, the more bitterly divided it became. To fully understand the vast changes the war unleashed on the country, you must first understand the plight of the Southerners who didn't want secession". American Heritage. Vol. 40 no. 2. American Heritage Publishing Company. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 1, 1970. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

Further reading

- Barrett, John G. The Civil War in North Carolina. (University of North Carolina Press, 1963).

- Barrett, John Gilcrest. The Civil War in North Carolina. (North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1984).

- Carbone, John S. The Civil War in Coastal North Carolina. (North Carolina Division of Archives and History, 2001).

- Erslev, Major Brit K. Taming the Tar Heel Department: DH Hill and the Challenges of Operational-Level Command during the American Civil War (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015).

- Hardy, Michael C. North Carolina in the Civil War. The History Press, 2011.

- Inscoe, John C. and Gordon B. McKinney. The Heart of Confederate Appalachia: Western North Carolina in the Civil War. (University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

- Mobley, Joe A. Confederate Generals of North Carolina: Tar Heels in Command (Arcadia Publishing, 2012).

- Myers, Barton A. Rebels Against the Confederacy: North Carolina's Unionists. (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- Poteat, R. Matthew (2009). Henry Toole Clark: Civil War Governor of North Carolina. McFarland. pp. 90–118.

- Reid, Richard M. Freedom for Themselves: North Carolina's Black Soldiers in the Civil War Era. (University of North Carolina Press, 2008).

Primary sources

- Clinard, Karen L. and Richard Russell (eds.) Fear in North Carolina: The Civil War Journals and Letters of the Henry Family. (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair Publishing, 2008).

- McSween, Murdoch John. Confederate Incognito: The Civil War Reports of" Long Grabs," aka Murdoch John McSween, 26th and 35th North Carolina Infantry (McFarland, 2012).

.svg.png)

.jpg)