Ninety-five Theses

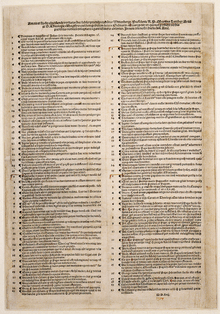

The Ninety-five Theses or Disputation on the Power of Indulgences (Latin: Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum[lower-alpha 1]) are a list of propositions for an academic disputation written by Martin Luther in 1517. They advance Luther's positions against what he saw as abusive practices by preachers selling plenary indulgences, which were certificates which would reduce the temporal punishment for sins committed by the purchaser or their loved ones in purgatory. Luther sent the Theses to Albert of Brandenburg, the Archbishop of Mainz, on 31 October 1517, a date now considered the start of the Protestant Reformation and commemorated annually as Reformation Day. Luther may have also posted the Theses on the door of All Saints' Church, Wittenberg and other churches in the city in accordance with University custom, probably in mid-November.

The Theses were quickly reprinted, translated, and distributed throughout Germany and Europe. They initiated a pamphlet war with indulgence preacher Johann Tetzel, which spread Luther's fame even further. Luther's ecclesiastical superiors had him tried for heresy, which culminated in his excommunication in 1521. The indulgence controversy and Luther's ensuing conflict with the Church was the beginning of the Protestant Reformation, a schism in the Catholic Church which profoundly changed Europe, though Luther did not consider indulgences to be as important as other theological matters which would divide the church, such as justification by faith and the bondage of the will.

Background

Martin Luther, professor of moral theology at the University of Wittenberg and town preacher,[2] wrote the Ninety-five Theses against the contemporary practice of the church with respect to indulgences. In the Catholic Church, indulgences are part of the economy of salvation. In this system, when Christians sin and confess, they are forgiven and will no longer receive eternal punishment in hell, but may still be liable to temporal punishment.[3] This punishment could be satisfied by the penitent performing works of mercy.[4] If the temporal punishment is not satisfied during life, it would need to be satisfied in purgatory. With an indulgence (which may be translated "kindness"), this temporal punishment could be lessened.[3] Under abuses of the system of indulgences, clergy benefited by selling indulgences and the pope gave official sanction in exchange for a fee.[5]

Popes are able to grant plenary indulgences, which provide complete satisfaction for any remaining temporal punishment due to sins, and were purchased on behalf of people in purgatory. This led to the popular saying, "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs". Theologians at the University of Paris had criticized this saying late in the fifteenth century.[6] Earlier critics of indulgences included John Wycliffe, who denied that the pope had jurisdiction over purgatory. Jan Hus and his followers had advocated a more severe system of penance where indulgences were not available.[7] Johannes von Wesel had also attacked indulgences late in the fifteenth century.[8] Political rulers had an interest in controlling indulgences because local economies suffered when the money for indulgences left a given territory. Rulers often sought to receive a portion of the proceeds or prohibited indulgences altogether.[9]

In 1515, Pope Leo X granted a plenary indulgence intended to finance the construction of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.[9] It would apply to almost any sin, including adultery and theft. All other indulgence preaching was to cease for the eight years in which it was offered. Indulgence preachers were given strict instructions on how the indulgence was to be preached, and they were much more laudatory of the indulgence than those of earlier indulgences.[10] Johann Tetzel was commissioned to preach and offer the indulgence in 1517, and his campaign in cities near Wittenberg drew many Wittenbergers to travel to these cities and purchase them. Duke George had prohibited Tetzel from actually entering Electoral Saxony, the state in which Wittenberg was located.[11]

Luther also had experience with the indulgences connected to All Saints' Church, Wittenberg.[12] By venerating the large collection of relics at the church, one could receive an indulgence.[13] He had preached as early as 1514 against the abuse of indulgences and the way they cheapened grace rather than requiring true repentance.[14] Luther became especially concerned in 1517 when his parishioners, returning from purchasing Tetzel's indulgences, claimed that they no longer needed to repent and change their lives in order to be forgiven of sin. After hearing what Tetzel had said about indulgences in his sermons, he began to study the issue more carefully and contacted experts on the subject. He preached about indulgences several times in 1517, explaining that true repentance was better than purchasing an indulgence.[15] He taught that receiving an indulgence presupposed that the penitent had confessed and repented, otherwise it was worthless. A truly repentant sinner would also not seek an indulgence, because they loved God's righteousness and desired the inward punishment of their sin.[16] These sermons seem to have ceased from April to October 1517, while Luther was presumably writing the Ninety-five Theses.[17] He composed a Treatise on Indulgences, apparently in early Autumn 1517. It is a cautious and searching examination of the subject.[18] He contacted church leaders on the subject by letter, including his superior Hieronymus Schulz, Bishop of Brandenburg, sometime on or before 31 October when he sent the Theses to Archbishop Albert of Brandenburg.[19]

Content

The first thesis has become famous: "When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, 'Repent,' he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance." In the first few theses Luther develops the idea of repentance as the Christian's inner struggle with sin rather than the external system of sacramental confession.[20] Theses 5–7 then state that the pope can only release people from the punishments he has administered himself or through the church's system of penance, not the guilt of sin. The pope is only able to announce God's forgiveness of the guilt of sin in his name.[21] In theses 14–16, Luther challenged common beliefs about purgatory, and in theses 17–24 he asserts that nothing can be definitively said about the spiritual state of people in purgatory. He denies that the pope has any power over people in purgatory in theses 25 and 26. In theses 27–29, he attacks the idea that as soon as payment is made, the payer's loved one is released from purgatory. He sees it as encouraging sinful greed and impossible to be certain because only God has ultimate power in forgiving punishments in purgatory.[22]

Theses 30–34 deal with the false certainty Luther believed the indulgence preachers offered Christians. Since no one knows whether a person is truly repentant, a letter assuring a person of his forgiveness is dangerous. In theses 35 and 36, he attacks the idea that an indulgence makes repentance unnecessary. This leads to the conclusion that the truly repentant person, who alone may benefit from the indulgence, has already received the only benefit the indulgence provides. Truly repentant Christians have already, according to Luther, been forgiven of the penalty as well as the guilt of sin.[22] In theses 37 and 38, he states that indulgences are not necessary for Christians to receive all the benefits provided by Christ. Theses 39 and 40 argue that indulgences make true repentance more difficult. True repentance desires God's punishment of sin, but indulgences teach one to avoid punishment, since that is the purpose of purchasing the indulgence.[23]

In theses 41–47 Luther begins to criticize indulgences on the basis that they discourage works of mercy by those who purchase them. Here he begins to use the phrase, "Christians are to be taught..." to state how he thinks people should be instructed on the value of indulgences. They should be taught that giving to the poor is incomparably more important than buying indulgences, that buying an indulgence rather than giving to the poor invites God's wrath, and that doing good works makes a person better while buying indulgences does not. In theses 48–52 Luther takes the side of the pope, saying that if the pope knew what was being preached in his name he would rather St. Peter's Basilica be burned down than "built up with the skin, flesh, and bones of his sheep."[23] Theses 53–55 complain about the restrictions on preaching while the indulgence was being offered.[24]

Luther begins to criticize the doctrine of the treasury of merit on which the doctrine of indulgences is based in theses 56–66. He states that everyday Christians do not understand the doctrine and are being misled. For Luther, the true treasure of the church is the gospel of Jesus Christ. This treasure tends to be hated because it makes "the first last",[25] in the words of Matthew 19:30 and 20:16.[26] Luther uses metaphor and wordplay to describe the treasures of the gospel as nets to catch wealthy people, whereas the treasures of indulgences are nets to catch the wealth of men.[25]

In theses 67–80, Luther discusses further the problems with the way indulgences are being preached, as he had done in the letter to Archbishop Albert. The preachers have been promoting indulgences as the greatest of the graces available from the church, but they actually only promote greed. He points out that bishops have been commanded to offer reverence to indulgence preachers who enter their jurisdiction, but bishops are also charged with protecting their people from preachers who preach contrary to the pope's intention.[25] He then attacks the belief allegedly propagated by the preachers that the indulgence could forgive one who had violated the Virgin Mary. Luther states that indulgences cannot take away the guilt of even the lightest of venial sins. He labels several other alleged statements of the indulgence preachers as blasphemy: that Saint Peter could not have granted a greater indulgence than the current one, and that the indulgence cross with the papal arms is as worthy as the cross of Christ.[27]

Luther lists several criticisms advanced by laypeople against indulgences in theses 81–91. He presents these as difficult objections his congregants are bringing rather than his own criticisms. How should he answer those who ask why the pope does not simply empty purgatory if it is in his power? What should he say to those who ask why anniversary masses for the dead, which were for the sake of those in purgatory, continued for those who had been redeemed by an indulgence? Luther claimed that it seemed strange to some that pious people in purgatory could be redeemed by living impious people. Luther also mentions the question of why the pope, who is very rich, requires money from poor believers to build St. Peter's Basilica. Luther claims that ignoring these questions risks allowing people to ridicule the pope.[27] He appeals to the pope's financial interest, saying that if the preachers limited their preaching in accordance with Luther's positions on indulgences (which he claimed was also the pope's position), the objections would cease to be relevant.[28] Luther closes the Theses by exhorting Christians to imitate Christ even if it brings pain and suffering. Enduring punishment and entering heaven is preferable to false security.[29]

Luther's intent

The Theses are written as propositions to be argued in a formal academic disputation,[30] though there is no evidence that such a disputation ever took place.[31] In the heading of the Theses, Luther invited interested scholars from other cities to participate in the disputation. Holding such a disputation was a privilege Luther held as a doctor, and it was not an unusual form of academic inquiry.[30] Luther prepared twenty sets of theses for disputation at Wittenberg between 1516 and 1521.[32] Andreas Karlstadt had written theses for disputation in April 1517, and these were more radical in theological terms than Luther's. He posted them on the door of All Saints' Church, as Luther was alleged to have done with the Ninety-five Theses. Karlstadt posted his theses at a time when the relics of the church were placed on display, and this may have been considered a provocative gesture. Similarly, Luther posted the Ninety-five Theses on the most important day of the year for the display of relics at All Saints' Church.[33]

Luther's theses were intended to begin a debate among academics, not a popular revolution,[32] but there are indications that he saw his action as prophetic and significant. Around this time, he began using the name "Luther" and sometimes "Eleutherius", Greek for "free", rather than "Luder". This seems to refer to his being free from the scholastic theology which he had argued against earlier that year.[34] Luther later claimed not to have desired the Theses to be widely distributed. Elizabeth Eisenstein has argued that his claimed surprise at their success may have involved self-deception and Hans Hillerbrand has claimed that Luther was certainly intending to instigate a large controversy.[1] At times, Luther seems to use the academic nature of the Theses as a cover to allow him to attack established beliefs while being able to deny that he intended to attack church teaching. Since writing a set of theses for a disputation does not necessarily commit the author to those views, Luther could deny that he held the most incendiary ideas in the Theses.[35]

Distribution and publication

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

On 31 October 1517, Luther sent a letter to Archbishop of Mainz, Albert of Brandenburg, under whose authority the indulgences were being sold. In the letter, Luther addresses the archbishop out of a loyal desire to alert him to the pastoral problems created by the indulgence sermons. He assumes that Albert is unaware of what is being preached under his authority, and speaks out of concern that the people are being led away from the gospel, and that the indulgence preaching may bring shame to Albert's name. He does not condemn indulgences or the current doctrine regarding them, nor even the sermons which had been preached themselves, as he had not seen them firsthand. Instead he states his concern regarding the misunderstandings of the people about indulgences which have been fostered by the preaching, such as the belief that any sin could be forgiven by indulgences or that the guilt as well as the punishment for sin could be forgiven by an indulgence. In a postscript, Luther wrote that Albert could find some theses on the matter enclosed with his letter, so that he could see the uncertainty surrounding the doctrine of indulgences in contrast to the preachers who spoke so confidently of the benefits of indulgences.[36]

It was customary when proposing a disputation to have the theses printed by the university press and publicly posted.[37] No copies of a Wittenberg printing of the Ninety-five Theses have survived, but this is not surprising as Luther was not famous and the importance of the document was not recognized.[38][lower-alpha 2] In Wittenberg, the university statutes demand that theses be posted on every church door in the city, but Philip Melanchthon, who first mentioned the posting of the theses, only mentioned the door of All Saints' Church.[lower-alpha 3][40] Melanchthon also claimed that Luther posted the Theses on 31 October, but this conflicts with several of Luther's statements about the course of events,[30] and Luther always claimed that he brought his objections through proper channels rather than inciting a public controversy.[41] It is possible that while Luther later saw the 31 October letter to Albert as the beginning of the Reformation, he did not post the Theses to the church door until mid-November, but he may not have posted them on the door at all.[30] Regardless, the Theses were well-known among the Wittenberg intellectual elite soon after Luther sent them to Albert.[38]

The Theses were copied and distributed to interested parties soon after Luther sent the letter to Archbishop Albert.[42] The Latin Theses were printed in a four-page pamphlet in Basel, and as placards in Leipzig and Nuremberg.[43] In all, several hundred copies of the Latin Theses were printed in Germany in 1517. Kaspar Nützel in Nuremberg translated them into German later that year, and copies of this translation were sent to several interested parties across Germany,[42] but it was not necessarily printed.[44][lower-alpha 4]

Reaction

Albert seems to have received Luther's letter with the Theses around the end of November. He requested the opinion of theologians at the University of Mainz and conferred with his advisers. His advisers recommended he have Luther prohibited from preaching against indulgences in accordance with the indulgence bull. Albert requested such action from the Roman Curia.[46] In Rome, Luther was immediately perceived as a threat.[47] In February 1518, Pope Leo asked the head of the Augustinian Hermits, Luther's religious order, to convince him to stop spreading his ideas about indulgences.[46] Sylvester Mazzolini was also appointed to write an opinion which would be used in the trial against him.[48] Mazzolini wrote A Dialogue against Martin Luther's Presumptious Theses concerning the Power of Pope, which focused on Luther's questioning of the pope's authority rather than his complaints about indulgence preaching.[49] Luther received a summons to Rome in August 1518.[48] He responded with Explanations of the Disputation Concerning the Value of Indulgences, in which he attempted to clear himself of the charge that he was attacking the pope.[49] As he set down his more extensively, Luther seems to have recognized that the implications of his beliefs set him further from official teaching than he initially knew. He later said he may not have begun the controversy had he known where it would lead.[50] The Explanations have been called Luther's first Reformation work.[51]

Johann Tetzel responded to the Theses by calling for Luther to be burnt for heresy and having theologian Konrad Wimpina write 106 theses against Luther's work. Tetzel defended these in a disputation before the University of Frankfurt on the Oder in January 1518.[52] 800 copies of the printed disputation were sent to be sold in Wittenberg, but students of the University seized them from the bookseller and burned them. Luther became increasingly fearful that the situation was out of hand and that he would be in danger. To placate his opponents, he published a Sermon on Indulgences and Grace, which did not challenge the pope's authority.[53] This pamphlet, written in German, was very short and easy for laypeople to understand.[44] Luther's first widely successful work, it was reprinted twenty times.[54] Tetzel responded with a point-by-point refutation, citing heavily from the Bible and important theologians.[55][lower-alpha 5] His pamphlet was not nearly as popular as Luther's. Luther's reply to Tetzel's pamphlet, on the other hand, was another publishing success for Luther.[57][lower-alpha 6]

Another prominent opponent of the Theses was Johann Eck, Luther's friend and a theologian at the University of Ingolstadt. Eck wrote a refutation, intended for the Bishop of Eichstätt, entitled the Obelisks. This was in reference to the obelisks used to mark heretical passages in texts in the Middle Ages. It was a harsh and unexpected personal attack, charging Luther with heresy and stupidity. Luther responded privately with the Asterisks, titled after the asterisk marks then used to highlight important texts. Luther's response was angry and he expressed the opinion that Eck did not understand the matter on which he wrote.[59] The dispute between Luther and Eck would become public in the 1519 Leipzig Debate.[55]

Luther was summoned by authority of the pope to defend himself against charges of heresy before Thomas Cajetan at Augsburg in October 1518. Cajetan did not allow Luther to argue with him over his alleged heresies, but he did identify two points of controversy. The first was against the fifty-eighth thesis, which stated that the pope could not use the treasury of merit to forgive temporal punishment of sin.[60] This contradicted the papal bull Unigenitus promulgated by Clement VI in 1343.[61] The second point was whether one could be assured that they had been forgiven when their sin had been absolved by a priest. Luther's Explanations on thesis seven asserted that one could based on God's promise, but Cajetan argued that the humble Christian should never presume to be certain of their standing before God.[60] Luther refused to recant and requested that the case be reviewed by university theologians. This request was denied, so Luther appealed to the pope before leaving Augsburg.[62] Luther was finally excommunicated in 1521 after he burned the papal bull threatening him to recant or face excommunication.[63]

Legacy

The indulgence controversy set off by the Theses was the beginning of the Protestant Reformation, a schism in the Catholic Church which initiated profound social and political change in Europe.[64] Luther later stated that the issue of indulgences was insignificant relative to controversies he would enter into later, such as his debate with Erasmus over the bondage of the will,[65] nor did he see the controversy as important to his intellectual breakthrough regarding the gospel.[41] But it was out of the indulgences controversy that the movement which would be called the Reformation began, and the controversy propelled Luther to the leadership position he would hold in that movement.[65] The Theses also made evident that Luther believed the church was not preaching properly and that this put the laity in serious danger. Further, the Theses contradicted the decree of Pope Clement VI, that indulgences are the treasury of the church. This disregard for papal authority presaged later conflicts.[66]

31 October 1517, the day Luther sent the Theses to Albert, was commemorated as the beginning of the Reformation as early as 1527, when Luther and his friends raised a glass of beer to commemorate the "trampling out of indulgences".[67] The posting of the Theses was established in the historiography of the Reformation as the beginning of the movement by Philip Melanchthon in his 1548 Historia de vita et actis Lutheri. During the 1617 Reformation Jubilee, the centenary of 31 October was celebrated by a procession to the Wittenberg Church where Luther was believed to have posted the Theses. An engraving was made showing Luther writing the Theses on the door of the church with a gigantic quill. The quill penetrates the head of a lion symbolizing Pope Leo X.[68] In 1668, 31 October was made Reformation Day, an annual festival in Electoral Saxony, which spread to other Lutheran lands.[69]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ This title comes from the 1517 Basel pamphlet printing. The first printings of the Theses use an incipit rather than a title which summarizes the content. The 1517 Nuremberg placard edition opens Amore et studio elucidande veritatis: hec subscripta disputabuntur Wittenberge. Presidente R.P Martino Lutther ... Quare petit: vt qui non possunt verbis presentes nobiscum disceptare: agant id Uteris absentes. Luther usually called them "meine Propositiones" (my propositions).[1]

- ↑ The Wittenberg printer was Johann Rhau-Grunenberg. A Rhau-Grunenberg printing of Luther's "Disputation Against Scholastic Theology", published just eight weeks before the Ninety-five Theses, was discovered in 1983.[39] Its form is very similar to that of the Nuremberg printing of the Ninety-five Theses. This is evidence for a Rhau-Grunenberg printing of the Ninety-five Theses, as the Nuremberg printing may be a copy of the Wittenberg printing.[38]

- ↑ Georg Rörer, Luther's scribe, claimed in a note that Luther posted the theses to every church door.

- ↑ No copies of the 1517 German translation survive.[45]

- ↑ Tetzel's pamphlet is titled Rebuttal Against a Presumptuous Sermon of Twenty Erroneous Articles.[56]

- ↑ Luther's reply to Tetzel's Rebuttal is titled Concerning the Freedom of the Sermon on Papal Indulgences and Grace. Luther intends to free the Sermon from Tetzel's insults.[58]

References

- 1 2 Cummings 2002, p. 32.

- ↑ Junghans 2003, pp. 23, 25.

- 1 2 Brecht 1985, p. 176.

- ↑ Wengert 2015a, p. xvi.

- ↑ Noll 2015, p. 31.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 182.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 177.

- ↑ Waibel 2005, p. 47.

- 1 2 Brecht 1985, p. 178.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 180.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 183.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 186.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 185.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 184.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 187.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 188.

- ↑ Wicks 1967, p. 489.

- ↑ Leppin & Wengert 2015, p. 387.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 192.

- ↑ Waibel 2005, p. 43.

- 1 2 Brecht 1985, p. 194.

- 1 2 Brecht 1985, p. 195.

- ↑ Waibel 2005, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 Brecht 1985, p. 196.

- ↑ Wengert 2015a, p. 22.

- 1 2 Brecht 1985, p. 197.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 198.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 199.

- 1 2 3 4 Brecht 1985, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Leppin & Wengert 2015, p. 388.

- 1 2 Hendrix 2015, p. 61.

- ↑ McGrath 2011, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Lohse 1999, p. 101.

- ↑ Cummings 2002, p. 35.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, pp. 190–192.

- ↑ Pettegree 2015, p. 128.

- 1 2 3 Pettegree 2015, p. 129.

- ↑ Pettegree 2015, p. 97.

- ↑ Wengert 2015b, p. 23.

- 1 2 Marius 1999, p. 138.

- 1 2 Hendrix 2015, p. 62.

- ↑ Cummings 2002, p. 32; Hendrix 2015, p. 62.

- 1 2 Leppin & Wengert 2015, p. 389.

- ↑ Oberman 2006, p. 191.

- 1 2 Brecht 1985, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Pettegree 2015, p. 152.

- 1 2 Brecht 1985, p. 242.

- 1 2 Hendrix 2015, p. 66.

- ↑ Marius 1999, p. 145.

- ↑ Lohse 1986, p. 125.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, pp. 206–207.

- ↑ Hendrix 2015, p. 64.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, pp. 208–209.

- 1 2 Hendrix 2015, p. 65.

- ↑ Pettegree 2015, p. 144.

- ↑ Pettegree 2015, p. 145.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 209.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 212.

- 1 2 Hequet 2015, p. 124.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 253.

- ↑ Hequet 2015, p. 125.

- ↑ Brecht 1985, p. 427.

- ↑ Dixon 2002, p. 23.

- 1 2 McGrath 2011, p. 26.

- ↑ Wengert 2015a, p. xliii–xliv.

- ↑ Stephenson 2010, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Cummings 2002, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Stephenson 2010, p. 40.

Sources

- Brecht, Martin (1985) [1981]. Sein Weg zur Reformation 1483–1521 [Martin Luther: His Road to Reformation 1483–1521] (in German). Translated by James L. Schaff. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress. ISBN 978-0-8006-2813-0 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Cummings, Brian (2002). The Literary Culture of the Reformation: Grammar and Grace. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198187356.001.0001 – via Oxford Scholarship Online. (subscription required (help)).

- Dixon, C. Scott (2002). The Reformation in Germany. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell.

- Hendrix, Scott H. (2015). Martin Luther: Visionary Reformer. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16669-9.

- Hequet, Suzanne (2015). "The Proceedings at Augsburg, 1518". In Wengert, Timothy J. The Annotated Luther, Volume 1: The Roots of Reform. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress. pp. 121–166. ISBN 978-1-4514-6535-8 – via Project MUSE. (subscription required (help)).

- Junghans, Helmar (2003). "Luther's Wittenberg". In McKim, Donald K. Cambridge Companion to Martin Luther. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 20–36 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Leppin, Volker; Wengert, Timothy J. (2015). "Sources for and against the Posting of the Ninety-Five Theses" (PDF). Lutheran Quarterly. 29: 373–398.

- Lohse, Bernhard (1999) [1995]. Luthers Theologie in ihrer historischen Entwicklung und in ihrem systematischen Zusammenhang [Martin Luther's Theology: Its Historical and Systematic Development. Contributors] (in German). Translated by Roy A. Harrisville. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress. ISBN 978-0-8006-3091-1 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Lohse, Bernhard (1986) [1980]. Martin Luther—Eine Einfubrung in sein Leben und sein Werk [Martin Luther: An Introduction to His Life and Work] (in German). Translated by Robert C. Schultz. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress. ISBN 978-0-8006-0764-7 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Marius, Richard (1999). Martin Luther: The Christian Between God and Death. Cambridge, MA: Belknap. ISBN 978-0-674-55090-2.

- McGrath, Alister E. (2011). Luther's Theology of the Cross: Martin Luther's Theological Breakthrough. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Noll, Mark A. (2015). In the Beginning Was the Word: The Bible in American Public Life, 1492–1783. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190263980.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-026398-0 – via Oxford Scholarship Online. (subscription required (help)).

- Oberman, Heiko A. (2006) [1982]. Luther: Mensch zwischen Gott und Teufel [Luther: Man Between God and the Devil] (in German). Translated by Eileen Walliser-Schwarzbart. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10313-7.

- Pettegree, Andres (2015). Brand Luther. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-59420-496-8.

- Palmer, R. R., A History of the Modern World (New York: McGraw Hill, 2002) ISBN 0-375-41398-7

- Waibel, Paul R. (2005). Martin Luther: A Brief Introduction to His Life and Works. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson. ISBN 978-0-88295-231-4 – via Questia. (subscription required (help)).

- Stephenson, Barry (2010). Performing the Reformation: Religious Festivals in Contemporary Wittenberg. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199732753.001.0001 – via Oxford Scholarship Online. (subscription required (help)).

- Wengert, Timothy J. (2015a). Martin Luther's Ninety-Five Theses: With Introduction, Commentary, and Study Guide. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress – via Project MUSE. (subscription required (help)).

- Wengert, Timothy J. (2015b). "[The 95 Theses or] Disputation for Clarifying the Power of Indulgences, 1517". In Wengert, Timothy J. The Annotated Luther, Volume 1: The Roots of Reform. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress. pp. 13–46. ISBN 978-1-4514-6535-8 – via Project MUSE. (subscription required (help)).

- Wicks, Jared (1967). "Martin Luther's Treatise on Indulgences" (PDF). Theological Studies. 28 (3): 481–518.

External links

- Ninety-five Theses at Project Gutenberg

-

The Ninety-Five Theses public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Ninety-Five Theses public domain audiobook at LibriVox

.jpg)