New Statesman

| |

| Editor | Jason Cowley |

|---|---|

| Categories | Politics, culture and foreign affairs |

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Total circulation (2015) | 33,395[1] |

| Founder | Sidney and Beatrice Webb |

| Year founded | 1913 |

| First issue | 12 April 1913 |

| Company | Progressive Digital Media |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Based in | London |

| Language | English |

| Website |

www |

| ISSN | 1364-7431 |

| OCLC number | 4588945 |

The New Statesman is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was connected then with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members of the socialist Fabian Society. The magazine has, according to its present self-description, a left-of-centre political position.[2]

The longest-serving editor was Kingsley Martin (1930–60). The current editor is Jason Cowley, who assumed the post at the end of September 2008. The magazine has notably recognized and published new writers and critics, as well as encouraged major careers. Its contributors have included John Maynard Keynes, Bertrand Russell, Virginia Woolf, Christopher Hitchens, and Paul Johnson.

Historically, the magazine was sometimes affectionately referred to as "The Staggers" because of crises in funding, ownership and circulation. The nickname is now used as the title of its politics blog.[3] Its regular writers, critics and columnists include Mehdi Hasan, Will Self, John Gray, Laurie Penny, Ed Smith, Stephen Bush and Helen Lewis, the deputy editor. Circulation peaked in the mid 1960s[4] and the magazine had a certified average circulation of 33,395 in 2015, up 14 per cent year-on-year. Traffic to the magazine's website reached a new record high in June 2016, with 27 million page views and four million unique users.[5]

In September 2014, as part of its digital expansion, the magazine launched two new websites, the urbanism-focused CityMetric and May2015.com, a data and polling site.

Early years

The New Statesman was founded in 1913 by Sidney and Beatrice Webb with the support of George Bernard Shaw and other prominent members of the Fabian Society.[6] Its first editor was Clifford Sharp, who remained editor until 1928. Desmond MacCarthy joined the paper in 1913 and became literary editor, recruiting Cyril Connolly to the staff in 1928.

In November 1914, three months after the beginning of the First World War, the New Statesmen published a lengthy anti-war supplement by George Bernard Shaw, "Common Sense About The War",[7] a scathing dissection of its causes, which castigated all nations involved but particularly savaged the British. It sold a phenomenal 75,000 copies by the end of the year and created an international sensation. The New York Times reprinted it as America began its lengthy debate on entering what was then called "the European War".[8]

During Sharp's last two years in the post, from around 1926, he was debilitated by chronic alcoholism and the paper was actually edited by his deputy Charles Mostyn Lloyd. Lloyd stood in after Sharp's departure until the appointment of Kingsley Martin as editor in 1930 – a position Martin was to hold for 30 years. Although the Webbs and most Fabians were closely associated with the Labour Party, Sharp was drawn increasingly to the Asquith Liberals.

1931–1960: Kingsley Martin

In 1931 the New Statesman merged with the Liberal weekly The Nation and Athenaeum and changed its name to the New Statesman and Nation, which it kept until 1964. The chairman of The Nation and Athenaeum's board was the economist John Maynard Keynes, who came to be an important influence on the newly merged paper, which started with a circulation of just under 13,000. It also absorbed The Week-end Review in 1934 (one element of which survives in the shape of the New Statesman's Weekly Competition, and the other the 'This England' feature).

During the 1930s, Martin's New Statesman moved markedly to the left politically. It became strongly anti-fascist and pacifist, opposing British rearmament.[9] After the 1938 Anschluss, Martin wrote: 'Today if Mr. Chamberlain would come forward and tell us that his policy was really one not only of isolation but also of Little Englandism in which the Empire was to be given up because it could not be defended and in which military defence was to be abandoned because war would totally end civilization, we for our part would wholeheartedly support him'.[10]

The magazine provoked further controversy with its coverage of Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union. In 1932, Keynes reviewed Martin's book on the Soviet Union, Low's Russian Sketchbook. Keynes argued that Martin was 'a little too full perhaps of good will' towards Stalin, and that any doubts about Stalin's rule had 'been swallowed down if possible'.[11] Martin was irritated by Keynes's article but still allowed it to be printed.[11] In a 17 September 1932 editorial, the magazine accused the British Conservative press of misrepresenting the Soviet Union's agricultural policy but added that 'the serious nature of the food situation is no secret and no invention'. The magazine defended the Soviet collectivization policy, but also said the policy had 'proceeded far too quickly and lost the cooperation of farmers'.[12] In 1934 it ran an interview with Stalin by H. G. Wells. Although sympathetic to aspects of the Soviet Union, Wells disagreed with Stalin on several issues.[11] The debate resulted in several more articles in the magazine; in one of them, George Bernard Shaw accused Wells of being disrespectful to Stalin during the interview.[11]

In 1938 came Martin's refusal to publish George Orwell's celebrated dispatches from Barcelona during the Spanish civil war because they criticised the communists for suppressing the anarchists and the left-wing Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM). 'It is an unfortunate fact,' Martin wrote to Orwell, 'that any hostile criticism of the present Russian regime is liable to be taken as propaganda against socialism'.[13] Martin also refused to allow any of the magazine's writers to review Leon Trotsky's anti-Stalinist book The Revolution Betrayed.[14]

Martin became more critical of Stalin after the Hitler-Stalin pact, claiming Stalin was 'adopting the familiar technique of the Fuhrer' and adding, 'Like Hitler, he [Stalin] has a contempt for all arguments except that of superior force.'[15] The magazine also condemned the Soviet Invasion of Finland.[16]

Circulation grew enormously under Martin's editorship, reaching 70,000 by the end of the Second World War. This number helped the magazine become a key player in Labour politics. The paper welcomed Labour's 1945 general election victory but took a critical line on the new government's foreign policy. The young Labour MP Richard Crossman, who had been an assistant editor for the magazine before the war, was Martin's chief lieutenant in this period, and the Statesman published Keep Left, the pamphlet written by Crossman, Michael Foot and Ian Mikardo, that most succinctly laid out the Labour left's proposals for a 'third force' foreign policy rather than alliance with the United States.

During the 1950s, the New Statesman remained a left critic of British foreign and defence policy and of the Labour leadership of Hugh Gaitskell, although Martin never got on personally with Aneurin Bevan, the leader of the anti-Gaitskellite Labour faction. The magazine opposed the Korean War, and an article by J. B. Priestley directly led to the founding of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

There was much less focus on a single political line in the back part of the paper, which was devoted to book reviews and articles on cultural topics. Indeed, with these pages managed by Janet Adam Smith, who was literary editor from 1952 to 1960, the paper was sometimes described as a pantomime horse: its back half was required reading even for many who disagreed with the paper's politics. This tradition would continue into the 1960s with Karl Miller as Smith's replacement.

After Kingsley Martin

Martin retired in 1960 and was replaced as editor by John Freeman, a politician and journalist who had resigned from the Labour government in 1951 with Bevan and Harold Wilson. Freeman left in 1965 and was followed in the chair by Paul Johnson, then on the left, under whose editorship the Statesman reached its highest ever circulation. For some, even enemies of Johnson such as Richard Ingrams, this was a strong period for the magazine editorially.

After Johnson's departure in 1970, the Statesman went into a long period of declining circulation under successive editors: Richard Crossman (1970–72), who tried to edit it at the same time as playing a major role in Labour politics; Anthony Howard (1972–78), whose recruits to the paper included Christopher Hitchens, Martin Amis and James Fenton (surprisingly, the arch anti-Socialist Auberon Waugh was writing for the Statesman at this time before returning to The Spectator).

Bruce Page (1978–82) moved the paper towards specialising in investigative journalism, sacking Arthur Marshall, who had been writing for the Statesman on and off since 1935, as a columnist, allegedly because of the latter's support for Margaret Thatcher. Hugh Stephenson (1982–86), under whom it took a strong position again for unilateral nuclear disarmament. John Lloyd (1986–87) swung the paper's politics back to the centre. Stuart Weir (1987–90), under whose editorship the Statesman founded the Charter 88 constitutional reform pressure group; and Steve Platt (1990–96).

The Statesman acquired the weekly New Society in 1988 and merged with it, becoming New Statesman and Society for the next eight years, then reverting to the old title, having meanwhile absorbed Marxism Today in 1991. In 1993, the Statesman was sued by Prime Minister John Major after it published an article that discussed rumours that Major was having an extramarital affair with a Downing Street caterer.[17] Although the action was settled out of court for a minimal sum,[18] the magazine's legal costs almost led to its closure.[19]

In 1994, KGB defector Yuri Shvets said that the KGB utilised the New Statesman to spread disinformation. Shvets said that the KGB had provided disinformation, including forged documents, to the New Statesman journalist Claudia Wright which she used for anti-American and anti-Israel stories in line with the KGB's campaigns.[20][21] By 1996 the magazine was selling 23,000 copies a week. New Statesman was the first periodical to go online, hosted by the www.cleanroom.co.uk, in 1995.

Since 1996

New Statesman was rescued from this near-bankruptcy by a takeover by businessman Philip Jeffrey but in 1996, after prolonged boardroom wrangling over Jeffrey's plans, it was sold to Geoffrey Robinson, the Labour MP and businessman.

Following Steve Platt's resignation, Robinson appointed as editor Ian Hargreaves, formerly editor of The Independent newspaper, on what was at the time an unprecedentedly high salary. Hargreaves in turn fired most of the left-wingers on the staff and turned the Statesman into a strong supporter of Tony Blair as Labour leader.

Hargreaves was succeeded by Peter Wilby, also from the Independent stable, who had previously been the Statesman's books editor, in 1998. Wilby attempted to reposition the paper back 'on the left'. His stewardship was not without controversy. In 2002, for example, the periodical was accused of antisemitism when it published an investigative cover story on the power of the "Zionist lobby" in Britain, under the title "A Kosher Conspiracy?".[22] The cover was illustrated with a gold Star of David towering over a Union Jack.[23] Wilby responded to the criticisms in a subsequent issue.[24] A year earlier Wilby was accused of being anti-American because of his reporting of 11 September attacks on New York and Washington.

John Kampfner, Wilby's political editor, succeeded him as editor in May 2005 following considerable internal lobbying. Under Kampfner's editorship, a relaunch in 2006 initially saw headline circulation climb to over 30,000. However, over 5,000 of these were apparently monitored free copies,[25] and Kampfner failed to maintain the 30,000 circulation he had pledged. In February 2008, Audit Bureau Circulation figures showed that circulation had plunged nearly 13% in 2007.[26] Kampfner resigned on 13 February 2008, the day before the ABC figures were made public, reportedly due to conflicts with Robinson over the magazine's marketing budget (which Robinson had apparently slashed in reaction to the fall in circulation).

In April 2008 Geoffrey Robinson sold a 50% interest in the magazine to businessman Mike Danson, and the remainder a year later.[27] The appointment of the new editor Jason Cowley was announced on 16 May 2008 but he did not take up the job until the end of September 2008.[28]

In January 2009, the magazine refused to recognise the National Union of Journalists, the trade union to which almost of all its journalists belonged, though further discussions were promised but never materialised.[29]

In 2009, Cowley was named current-affairs editor of the year at the British Society of Magazine Editors awards.[30] and in 2011, he was named editor of the year in the Newspaper & Current Affairs Magazine Category at the British Society of Magazine Editors awards, while Jon Bernstein, the deputy editor, gained the award for Consumer Website Editor of the Year.[31] Cowley has been shortlisted as Editor of the Year (consumer magazines) in the 2012 PPA (Professional Publishers Association) Awards.[32] In January 2013, Cowley was shortlisted for the European Press Prize editing award.[33] The awards committee said: “Cowley has succeeded in revitalising the New Statesman and re-establishing its position as an influential political and cultural weekly. He has given the New Statesman an edge and a relevance to current affairs it hasn’t had for years.”

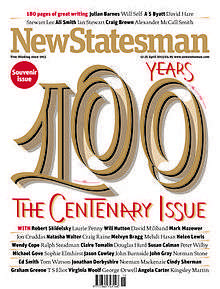

In April 2013 the magazine published a 186-page centenary special, the largest single issue in its history. The following year it expanded its web presence by establishing two new websites: May2015.com, a polling data site focused on the 2015 general election, and CityMetric, a cities magazine site under the tagline, "Urbanism for the social media age".

Guest editors

In March 2009 the magazine had its first guest editor, Alastair Campbell, the former head of communications for Tony Blair. Campbell chose to feature his partner Fiona Millar, Tony Blair (in an article "Why we must all do God"), football manager Alex Ferguson, and Sarah Brown, the wife of Prime Minister Gordon Brown. This editorship was condemned by Suzanne Moore, a contributor to the magazine for twenty years. She wrote in a Mail on Sunday article: "New Statesman fiercely opposed the Iraq war and yet now hands over the reins to someone key in orchestrating that conflict".[34] Campbell responded: "I had no idea she worked for the New Statesman. I don't read the Mail on Sunday. But professing commitment to leftwing values in that rightwing rag lends a somewhat weakened credibility to anything she says."[35]

In September 2009 the magazine was guest-edited by Labour politician Ken Livingstone, the former mayor of London.[36]

In October 2010 the magazine was guest-edited by the British author and broadcaster Melvyn Bragg. The issue included a previously unpublished poem[37] by Ted Hughes, "Last letter", describing what happened during the three days leading up to the suicide of his first wife, the poet Sylvia Plath. Its first line is: "What happened that night? Your final night."—and the poem ends with the moment Hughes is informed of his wife's death.

In April 2011 the magazine was guest-edited by the human rights activist Jemima Khan. The issue featured a series of exclusives including the actor Hugh Grant's secret recording[38] of former News of the World journalist Paul McMullan, and a much-commented-on[39] interview[40] with Liberal Democrat leader and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, in which Clegg admitted that he "cries regularly to music" and that his nine-year-old son asked him, "'Why are the students angry with you, Papa?'"

In June 2011 Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury created a furore as guest editor by claiming that the Coalition government had introduced "radical, long term policies for which no one had voted" and in doing so had created "anxiety and anger" among many in the country. He was accused of being highly partisan, notwithstanding his having invited Iain Duncan Smith, the Work and Pensions Secretary to write an article and having interviewed the Foreign Secretary William Hague in the same edition. He also noted that the Labour Party had failed to offer an alternative to what he called "associational socialism". The Statesman promoted the edition on the basis of Williams' alleged attack on the government, whereas Williams himself had ended his article by asking for "a democracy capable of real argument about shared needs and hopes and real generosity".

In December 2011 the magazine was guest-edited by Richard Dawkins. The issue included the writer Christopher Hitchens's final interview,[41] conducted by Dawkins in Texas, and pieces by Bill Gates, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett and Philip Pullman.

In October 2012 the magazine was guest-edited by Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei[42] and, for the first time, published simultaneously in Mandarin (in digital form) and English. To evade China's internet censors, the New Statesman uploaded the issue to file-sharing sites such as BitTorrent. As well as writing that week's editorial,[43] Ai Weiwei interviewed the Chinese civil rights activist Chen Guangcheng,[44] who fled to the United States after exposing the use of compulsory abortions and sterilisations. The issue was launched on 19 October 2012 at The Lisson Gallery in London,[45] where speakers including artist Anish Kapoor and lawyer Mark Stephens paid tribute to Ai Weiwei.

In October 2013 the magazine was guest-edited by Russell Brand, with contributions from David Lynch, Noel Gallagher, Naomi Klein, Rupert Everett, Amanda Palmer and Alec Baldwin,[46] as well as an essay by Brand.[47]

In October 2014, the magazine was guest-edited by the artist Grayson Perry, whose essay titled "Default Man" was widely discussed.

List of editors

|

|

See also

References

- ↑ "Consumer Magazines Combined Total Circulation Certificate January to December 2015" (PDF). ABC. 2016-09-17. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑

- ↑ Bush, Stephen (2016-11-13). "The Staggers". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Smith, Adrian (1995). The New Statesman: Portrait of a Political Weekly, 1913-1931. Portland, Oregon: F. Cass. ISBN 9780714641690.

- ↑ Statesman, New (2016-07-05). "Record traffic for the New Statesman website in June 2016". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ "Launching the New Statesman | From". The Guardian. 2008-04-09. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Current History, The European War Volume I, by The New York Times Company".

- ↑ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Current History, The European War Volume I, by The New York Times Company". Gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Morris, Benny (1991). The Roots of Appeasement: The British Weekly Press and Nazi Germany During the 1930s (1st ed.). London: F. Cass. p. 26, 65, 73, 118, 134, 156, 178. ISBN 9780714634173.

- ↑ , The Anti-Appeasers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), pp. 156-157.

- 1 2 3 4 Beasley, Rebecca; Bullock, Philip Ross (2013). Russia in Britain, 1880-1940: From Melodrama to Modernism (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 209–224. ISBN 0199660867.

- ↑ Wright, Patrick (2007). Iron Curtain: From Stage to Cold War. Oxford University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0199231508.

- ↑ Jones, Bill (1977). The Russia Complex: The British Labour Party and the Soviet Union. Manchester [Eng.]: Manchester University Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780719006968.

- ↑ Abu-Manneh, Bashir (2011). Fiction of the New Statesman, 1913-1939. Newark: University of Delaware Press. pp. 169–170. ISBN 1611493528.

- ↑ Moorhouse, Roger (2014). The Devils' Alliance: Hitler's Pact with Stalin, 1939-1941. Random House. p. cxxxviii. ISBN 1448104718.

- ↑ Corthorn, Paul (2006). In the Shadow of the Dictators: The British Left in the 1930s. London [u.a.]: Tauris Academic Studies. p. 215. ISBN 1850438439.

- ↑ "British Premier Is Suing Two Magazines for Libel". Great Britain: NYTimes.com. 1993-01-29. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Steve Platt, Fisk. "Sue, grab it and run the country: The Major libel case was a farce with a darker side, says Steve Platt, editor of the New Statesman". The Independent. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ "UK | Politics | Major faces legal action over affair". BBC News. 2002-09-29. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ The journal of intelligence history. International Intelligence History Association. p.63

- ↑ Dettmer, Jamie (12 February 1995). "Spies, in from the cold, snitch on collaborators". Insight on the News. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ↑ Sewell, Dennis (14 January 2002). "A Kosher Conspiracy?". New Statesman. Retrieved 26 August 2009

- ↑ Image of New Statesman Cover from Wikimedia Commons

- ↑ Wilby, Peter (11 February 2002). "The New Statesman and anti-Semitism". New Statesman. Retrieved 26 August 2009

- ↑ Wilby, Peter (18 February 2008). "The Statesman staggers on". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ Tryhorn, Chris (14 February 2008). "New Statesman sales plummet". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ James Robinson. "Mike Danson takes full ownership of New Statesman | Media". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Stephen Brook, press correspondent. "Jason Cowley named as New Statesman editor | Media". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Owen Amos "New Statesman management to discuss NUJ recognition", UK Press Gazette, 16 January 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ↑ Mark Sweney. "Morgan Rees of Men's Health named editors' editor at BSME awards | Media". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ "BSME". Web.archive.org. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ By admin Twitter (2012-04-16). "PPA Awards 2012: The shortlist – Press Gazette". Blogs.pressgazette.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑

- ↑ Moore, Suzanne (2009-03-24). "SUZANNE MOORE: I had to resign from the New Statesman when I saw what Alastair Campbell did to it | Daily Mail Online". Mailonsunday.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Owen Bowcott (2009-03-23). "Knives out at New Statesman as Alastair Campbell editing stint sparks 'crisis of faith' | Media". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Stephen Brook (2009-09-15). "Ken Livingstone is New Statesman guest editor | Media". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Maev Kennedy (2010-10-06). "Unknown poem reveals Ted Hughes' torment over death of Sylvia Plath | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Esther Addley (2011-04-06). "Phone hacking: Hugh Grant taped former NoW journalist | Media". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ "Nick Clegg, you chose to be coalition arm-candy, so accept being a punchbag | Simon Jenkins | Opinion". The Guardian. 2011-04-07. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Phillipson, Bridget (2011-04-07). "Jemima Khan meets Nick Clegg: "I'm not a punchbag – I have feelings"". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Reeves, Rachel (2011-12-13). "Preview: Richard Dawkins interviews Christopher Hitchens". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Statesman, New (2012-10-07). "Ai Weiwei to guest-edit the New Statesman". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Weiwei, Ai (2012-10-17). "To move on from oppression, China must recognise itself". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Weiwei, Ai (2012-10-17). "Chen Guangcheng: "Facts have blood as evidence"". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Reeves, Rachel (2012-10-19). "In pictures: Ai Weiwei launch party". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Reeves, Rachel (2013-10-25). "In this week's New Statesman: Russell Brand guest edit". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Brand, Russell (October 24, 2013). "Russell Brand on revolution: "We no longer have the luxury of tradition"". The New Statesman. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

Further reading

- Howe, Stephen (ed.). Lines of Dissent: Writing from the New Statesman, 1913 to 1988, Verso, 1988, ISBN 0-86091-207-8

- Hyams, Edward. The New Statesman: The History of the First Fifty Years, 1913–63, Longman, 1963.

- Rolph, C. H. (ed.). Kingsley: The Life, Letters and Diaries of Kingsley Martin, Victor Gollancz, 1973, ISBN 0-575-01636-1

- Smith, Adrian. The New Statesman: Portrait of a Political Weekly, 1913–1931, Frank Cass, 1996, ISBN 0-7146-4645-8

External links

- New Statesman

- The Spirit of Che Guevara by I F Stone, New Statesman 20 October 1967

- New Statesman Archive, 1944-1988