National Insurance Act 1911

|

| |

| Long title | An Act to provide for Insurance against Loss of Health and for the Prevention and Cure of Sickness and for Insurance against Unemployment, and for purposes incidental thereto. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 1911 c. 55 |

| Territorial extent | England and Wales; Scotland; Northern Ireland |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 16 December 1911 |

Status: Repealed | |

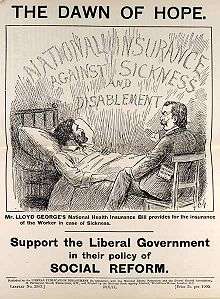

The National Insurance Act 1911 is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act is often regarded as one of the foundations of modern social welfare in the United Kingdom and forms part of the wider social welfare reforms of the Liberal Government of 1906–1915.

Background

Britain was not the first country to provide insured benefits. Germany had provided compulsory national insurance against sickness from 1884. After visiting Germany in 1908, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George said in his 1909 Budget Speech, that the United Kingdom should aim to be "putting ourselves in this field on a level with Germany; We should not emulate them only in armaments." In 1908 David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Liberal government led by H. H. Asquith proposed the 1911 National Insurance Act. This measure gave the British working classes the first contributory system of insurance against illness and unemployment. The Act only applied to waged earners, however, and their families and the unwaged had to rely on other sources of support, if any.[1]

A large section of the Conservative party opposed the Act[2] believing that taxpayers should not pay for such benefits and the leader of the Conservative party, Bonar Law, threatened to repeal the Act if the conservatives gained power.[3] Some trade unions who operated their own insurance schemes and friendly societies were also opposed.[4] The Act was important as it removed the need for unemployed workers, who were insured under the scheme, to rely on the stigmatised social welfare provisions of the Poor Law. This hastened the end of the Poor Law as a social welfare provider, with the Poor Law unions being abolished in 1929, and the administration of poor relief being transferred to the counties and county boroughs.[5]

Key figures in the implementation of the Act included Robert Laurie Morant, and William Braithwaite.

Franco-British Catholic writer Hilaire Belloc considered the Insurance Act to be a manifestation of The Servile State, which he detailed in his book of the same name.[6]

Part I, Health

The National Insurance Act Part I provided for a National Insurance scheme with provision of medical benefits. All workers who earned under £160 a year had to pay 4 pence a week to the scheme; the employer paid 3 pence, and general taxation paid 2 pence (Lloyd George called it the "ninepence for fourpence"). As a result, workers could take sick leave and be paid 10 shillings a week for the first 13 weeks and 5 shillings a week for the next 13 weeks. Workers also gained access to free treatment for tuberculosis, and the sick were eligible for treatment by a panel doctor. Due to pressure from the Co-operative Women's Guild, the National Insurance Act provided maternity benefits.

In parts of Scotland which were still largely subsistence farming the collection of cash contributions was impractical. The Highlands and Islands Medical Service was established in the crofting counties on a non-contributory basis in 1913.

Part II, Unemployment

National Insurance Act Part II provided for time-limited unemployment benefit. The scheme was to be based on actuarial principles and it was planned that it would be funded by a fixed amount each from workers, employers, and taxpayers. The scheme from Part II was restricted to particular industries, cyclical/seasonal industries like construction of ships, and neither made any provision for dependants. Part II worked in a similar way to Part I. The worker gave 2.5 pence/week when employed, the employer 2.5 pence, and the taxpayer 3 pence. After one week of unemployment, the worker would be eligible to receive 7 shillings/week for up to 15 weeks in a year. The money would be collected from labour exchanges.

By 1913, 2.3 million were insured under the scheme for unemployment benefit and almost 15 million insured for sickness benefit.

A key assumption of the Act was an unemployment rate of 4.6%. At the time the Act was passed unemployment was at 3% and the fund was expected to quickly build a surplus. Under the Act, employees' contributions to the scheme were to be compulsory and taken by the employer before the workers' salary was paid.

See also

- Old Age Pensions Act 1908

- United Kingdom general election, 1910

- Timeline of pensions in the United Kingdom

- Beveridge Report 1942

- National Health Service Act 1946

- Universal health care

References and sources

- References

- ↑ The Cabinet Papers 1915-1982: National Health Insurance Act 1911. The National Archives, 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ "SOCIAL INSURANCE SERVICES. (Hansard, 22 February 1939)". hansard.millbanksystems.com. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ↑ "DEBATE ON THE ADDRESS. (Hansard, 14 February 1912)". hansard.millbanksystems.com. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ↑ Clinton, Alan (1977-01-01). The Trade Union Rank and File: Trades Councils in Britain, 1900-40. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719006555.

- ↑ "English Poor Laws". eh.net. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ↑ Barker, Rodney (2013-01-11). Political Ideas in Modern Britain: In and After the Twentieth Century. Routledge. ISBN 9781134910663.

- Sources

- I Gazeley, Poverty in Britain 1900-1945 (Palgrave 2003)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Insurance. |

- Text of the Act

- Background to health provision

- The National insurance act, 1911; being a treatise on the scheme of national health insurance and insurance against unemployment created by that act by Orme Clarke, 1912.

.svg.png)