Endosome

In cell biology, an endosome is a membrane-bound compartment inside eukaryotic cells. It is a compartment of the endocytic membrane transport pathway originating from the trans Golgi membrane. Molecules or ligands internalized from the plasma membrane can follow this pathway all the way to lysosomes for degradation, or they can be recycled back to the plasma membrane. Molecules are also transported to endosomes from the trans-Golgi network and either continue to lysosomes or recycle back to the Golgi. Endosomes can be classified as early, sorting, or late depending on their stage post internalization.[1] Endosomes represent a major sorting compartment of the endomembrane system in cells.[2] In HeLa cells, endosomes are approximately 500 nm in diameter when fully mature.[3]

Function

Endosomes provide an environment for material to be sorted before it reaches the degradative lysosome.[2] For example, LDL is taken into the cell by binding to the LDL receptor at the cell surface. Upon reaching early endosomes, the LDL dissociates from the receptor, and the receptor can be recycled to the cell surface. The LDL remains in the endosome and is delivered to lysosomes for processing. LDL dissociates because of the slightly acidified environment of the early endosome, generated by a vacuolar membrane proton pump V-ATPase. On the other hand, EGF and the EGF receptor have a pH-resistant bond that persists until it is delivered to lysosomes for their degradation. The mannose 6-phosphate receptor carries ligands from the Golgi destined for the lysosome by a similar mechanism.

Types

Endosomes comprise three different compartments: early endosomes, late endosomes, and recycling endosomes.[2] They are distinguished by the time it takes for endocytosed material to reach them, and by markers such as rabs.[4] They also have different morphology. Once endocytic vesicles have uncoated, they fuse with early endosomes. Early endosomes then mature into late endosomes before fusing with lysosomes.[5][6]

Early endosomes mature in several ways to form late endosomes. They become increasingly acidic mainly through the activity of the V-ATPase.[7] Many molecules that are recycled are removed by concentration in the tubular regions of early endosomes. Loss of these tubules to recycling pathways means that late endosomes mostly lack tubules. They also increase in size due to the homotypic fusion of early endosomes into larger vesicles.[8] Molecules are also sorted into smaller vesicles that bud from the perimeter membrane into the endosome lumen, forming lumenal vesicles; this leads to the multivesicular appearance of late endosomes and so they are also known as multivesicular bodies (MVBs). Removal of recycling molecules such as transferrin receptors and mannose 6-phosphate receptors continues during this period, probably via budding of vesicles out of endosomes.[5] Finally, the endosomes lose RAB5A and acquire RAB7A, making them competent for fusion with lysosomes.[8]

Fusion of late endosomes with lysosomes has been shown to result in the formation of a 'hybrid' compartment, with characteristics intermediate of the two source compartments.[9] For example, lysosomes are more dense than late endosomes, and the hybrids have an intermediate density. Lysosomes reform by recondensation to their normal, higher density. However, before this happens, more late endosomes may fuse with the hybrid.

Some material recycles to the plasma membrane directly from early endosomes,[10] but most traffics via recycling endosomes.

- Early endosomes consist of a dynamic tubular-vesicular network (vesicles up to 1 µm in diameter with connected tubules of approx. 50 nm diameter). Markers include RAB5A and RAB4, Transferrin and its receptor and EEA1.

- Late endosomes, also known as MVBs, are mainly spherical, lack tubules, and contain many close-packed lumenal vesicles. Markers include RAB7, RAB9, and mannose 6-phosphate receptors.[11]

- Recycling endosomes are concentrated at the microtubule organizing center and consist of a mainly tubular network. Marker; RAB11.[12]

More subtypes exist in specialized cells such as polarized cells and macrophages.

Phagosomes, macropinosomes and autophagosomes[13] mature in a manner similar to endosomes, and may require fusion with normal endosomes for their maturation. Some intracellular pathogens subvert this process, for example, by preventing RAB7 acquisition.[14]

Late endosomes/MVBs are sometimes called endocytic carrier vesicles, but this term was used to describe vesicles that bud from early endosomes and fuse with late endosomes. However, several observations (described above) have now demonstrated that it is more likely that transport between these two compartments occurs by a maturation process, rather than vesicle transport.

Another unique identifying feature that differs between the various classes of endosomes is the lipid composition in their membranes. Phosphotidyl inositol phosphates (PIPs), one of the most important lipid signaling molecules, is found to differ as the endosomes mature from early to late. PI(4,5)P2 is present on plasma membranes, PIP3 on early endosomes, PI(3,5)P2 on late endosomes and PIP4 on the trans Golgi network.[15] These lipids on the surface of the endosomes help in the specific recruitment of proteins from the cytosol, thus providing them an identity. The inter-conversion of these lipids is a result of the concerted action of phosphoinositide kinases and phosphatases that are strategically localized [16]

Pathways

There are three main compartments that have pathways that connect with endosomes. More pathways exist in specialized cells, such as melanocytes and polarized cells. For example, in epithelial cells, a special process called transcytosis allows some materials to enter one side of a cell and exit from the opposite side. Also, in some circumstances, late endosomes/MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane instead of with lysosomes, releasing the lumenal vesicles, now called exosomes, into the extracellular medium.

It should be noted that there is no consensus as to the exact nature of these pathways, and the sequential route taken by any given cargo in any given situation will tend to be a matter of debate.

Golgi to/from endosomes

Vesicles pass between the Golgi and endosomes in both directions. The GGAs and AP-1 clathrin-coated vesicle adaptors make vesicles at the Golgi that carry molecules to endosomes.[17] In the opposite direction, retromer generates vesicles at early endosomes that carry molecules back to the Golgi. Some studies describe a retrograde traffic pathway from late endosomes to the Golgi that is mediated by Rab9 and TIP47, but other studies dispute these findings. Molecules that follow these pathways include the mannose-6-phosphate receptors that carry lysosomal hydrolases to the endocytic pathway. The hydrolases are released in the acidic environment of endosomes, and the receptor is retrieved to the Golgi by retromer and Rab9.

Plasma membrane to/from early endosomes (via recycling endosomes)

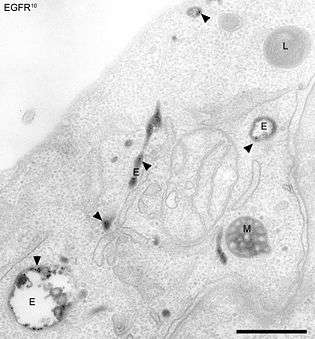

Molecules are delivered from the plasma membrane to early endosomes in endocytic vesicles. Molecules can be internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis in clathrin-coated vesicles. Other types of vesicles also form at the plasma membrane for this pathway, including ones utilising caveolin. Vesicles also transport molecules directly back to the plasma membrane, but many molecules are transported in vesicles that first fuse with recycling endosomes.[18] Molecules following this recycling pathway are concentrated in the tubules of early endosomes. Molecules that follow these pathways include the receptors for LDL, the growth factor EGF, and the iron transport protein transferrin. Internalization of these receptors from the plasma membrane occurs by receptor-mediated endocytosis. LDL is released in endosomes because of the lower pH, and the receptor is recycled to the cell surface. Cholesterol is carried in the blood primarily by (LDL), and transport by the LDL receptor is the main mechanism by which cholesterol is taken up by cells. EGFRs are activated when EGF binds. The activated receptors stimulate their own internalization and degradation in lysosomes. EGF remains bound to the EGFR once it is endocytosed to endosomes. The activated EGFRs stimulate their own ubiquitination, and this directs them to lumenal vesicles (see below) and so they are not recycled to the plasma membrane. This removes the signaling portion of the protein from the cytosol and thus prevents continued stimulation of growth[19] - in cells not stimulated with EGF, EGFRs have no EGF bound to them and therefore recycle if they reach endosomes.[20] Transferrin also remains associated with its receptor, but, in the acidic endosome, iron is released from the transferrin, and then the iron-free transferrin (still bound to the transferrin receptor) returns from the early endosome to the cell surface, both directly and via recycling endosomes.[21]

Late endosomes to lysosomes

Transport from late endosomes to lysosomes is, in essence, unidirectional, since a late endosome is "consumed" in the process of fusing with a lysosome. Hence, soluble molecules in the lumen of endosomes will tend to end up in lysosomes, unless they are retrieved in some way. Transmembrane proteins can be delivered to the perimeter membrane or the lumen of lysosomes. Transmembrane proteins destined for the lysosome lumen are sorted into the vesicles that bud from the perimeter membrane into endosomes, a process that begins in early endosomes. When the endosome has matured into a late endosome/MVB and fuses with a lysosome, the vesicles in the lumen are delivered to the lysosome lumen. Proteins are marked for this pathway by the addition of ubiquitin.[22] The endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRTs) recognise this ubiquitin and sort the protein into the forming lumenal vesicles.[23] Molecules that follow these pathways include LDL and the lysosomal hydrolases delivered by mannose-6-phosphate receptors. These soluble molecules remain in endosomes and are therefore delivered to lysosomes. Also, the transmembrane EGFRs, bound to EGF, are tagged with ubiquitin and are therefore sorted into lumenal vesicles by the ESCRTs.

See also

References

- ↑ Stoorvogel, Willem; Strous, Ger J.; Geuze, Hans J.; Oorschot, Viola; Schwartzt, Alan L. (1991-03-05). "Late endosomes derive from early endosomes by maturation". Cell. 65 (3): 417–427. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90459-C. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 1850321.

- 1 2 3 Mellman I (1996). "Endocytosis and molecular sorting". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 12: 575–625. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.575. PMID 8970738.

- ↑ Ganley; et al. (December 2004). "Rab9 GTPase Regulates Late Endosome Size and Requires Effector Interaction for Its Stability". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 15 (12): 5420–5430. doi:10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0747. PMC 532021

. PMID 15456905.

. PMID 15456905. - ↑ Stenmark, H. (Aug 2009). "Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic". Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 10 (8): 513–25. doi:10.1038/nrm2728. PMID 19603039.

- 1 2 Futter, CE.; Pearse, A.; Hewlett, LJ.; Hopkins, CR. (Mar 1996). "Multivesicular endosomes containing internalized EGF-EGF receptor complexes mature and then fuse directly with lysosomes". J Cell Biol. 132 (6): 1011–23. doi:10.1083/jcb.132.6.1011. PMC 2120766

. PMID 8601581.

. PMID 8601581. - ↑ Luzio JP; Rous BA; Bright NA; Pryor PR; Mullock BM; Piper RC. (2000). "Lysosome-endosome fusion and lysosome biogenesis". Journal of Cell Science. 113: 1515–1524. PMID 10751143.

- ↑ Lafourcade, C.; Sobo, K.; Kieffer-Jaquinod, S.; Garin, J.; van der Goot, FG. (2008). Joly, Etienne, ed. "Regulation of the V-ATPase along the endocytic pathway occurs through reversible subunit association and membrane localization". PLoS ONE. 3 (7): e2758. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002758. PMC 2447177

. PMID 18648502.

. PMID 18648502. - 1 2 Rink, J.; Ghigo, E.; Kalaidzidis, Y.; Zerial, M. (Sep 2005). "Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes". Cell. 122 (5): 735–49. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.043. PMID 16143105.

- ↑ Mullock, BM.; Bright, NA.; Fearon, CW.; Gray, SR.; Luzio, JP. (Feb 1998). "Fusion of lysosomes with late endosomes produces a hybrid organelle of intermediate density and is NSF dependent". J Cell Biol. 140 (3): 591–601. doi:10.1083/jcb.140.3.591. PMC 2140175

. PMID 9456319.

. PMID 9456319. - ↑ Hopkins, CR; I.S. Trowbridge, IS. (1983). "Internalization and processing of transferrin and the transferrin receptor in human carcinoma A431 cells". Journal of Cell Biology. 97 (2): 508–21. doi:10.1083/jcb.97.2.508. PMC 2112524

. PMID 6309862.

. PMID 6309862. - ↑ Russell, MR.; Nickerson, DP.; Odorizzi, G. (Aug 2006). "Molecular mechanisms of late endosome morphology, identity and sorting". Curr Opin Cell Biol. 18 (4): 422–8. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2006.06.002. PMID 16781134.

- ↑ Ullrich, O.; Reinsch, S.; Urbé, S.; Zerial, M.; Parton, RG. (Nov 1996). "Rab11 regulates recycling through the pericentriolar recycling endosome". J Cell Biol. 135 (4): 913–24. doi:10.1083/jcb.135.4.913. PMC 2133374

. PMID 8922376.

. PMID 8922376. - ↑ Fader, CM.; Colombo, MI. (Jan 2009). "Autophagy and multivesicular bodies: two closely related partners". Cell Death Differ. 16 (1): 70–8. doi:10.1038/cdd.2008.168. PMID 19008921.

- ↑ Körner, U.; Fuss, V.; Steigerwald, J.; Moll, H. (Feb 2006). "Biogenesis of Leishmania major-harboring vacuoles in murine dendritic cells". Infect Immun. 74 (2): 1305–12. doi:10.1128/IAI.74.2.1305-1312.2006. PMC 1360340

. PMID 16428780.

. PMID 16428780. - ↑ van Meer, Gerrit; Voelker, Dennis R.; Feigenson, Gerald W. (2008-02-01). "Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 9 (2): 112–124. doi:10.1038/nrm2330. ISSN 1471-0072. PMC 2642958

. PMID 18216768.

. PMID 18216768. - ↑ Di Paolo, Gilbert; De Camilli, Pietro (2006-10-12). "Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics". Nature. 443 (7112): 651–657. doi:10.1038/nature05185. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17035995.

- ↑ Ghosh, P.; Kornfeld, S. (Jul 2004). "The GGA proteins: key players in protein sorting at the trans-Golgi network". Eur J Cell Biol. 83 (6): 257–62. doi:10.1078/0171-9335-00374. PMID 15511083.

- ↑ Grant, BD.; Donaldson, JG. (Sep 2009). "Pathways and mechanisms of endocytic recycling". Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 10 (9): 597–608. doi:10.1038/nrm2755. PMC 3038567

. PMID 19696797.

. PMID 19696797. - ↑ Futter, CE.; Collinson, LM.; Backer, JM.; Hopkins, CR. (Dec 2001). "Human VPS34 is required for internal vesicle formation within multivesicular endosomes". J Cell Biol. 155 (7): 1251–64. doi:10.1083/jcb.200108152. PMC 2199316

. PMID 11756475.

. PMID 11756475. - ↑ Felder, S.; Miller, K.; Moehren, G.; Ullrich, A.; Schlessinger, J.; Hopkins, CR. (May 1990). "Kinase activity controls the sorting of the epidermal growth factor receptor within the multivesicular body". Cell. 61 (4): 623–34. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90474-S. PMID 2344614.

- ↑ Dautry-Varsat, A. (Mar 1986). "Receptor-mediated endocytosis: the intracellular journey of transferrin and its receptor". Biochimie. 68 (3): 375–81. doi:10.1016/S0300-9084(86)80004-9. PMID 2874839.

- ↑ Hicke, L.; Dunn, R. (2003). "Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins". Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 19: 141–72. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.154617. PMID 14570567.

- ↑ Hurley, JH. (Feb 2008). "ESCRT complexes and the biogenesis of multivesicular bodies". Curr Opin Cell Biol. 20 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2007.12.002. PMC 2282067

. PMID 18222686.

. PMID 18222686.

- Alberts, Bruce; et al. (2004). Essential Cell Biology (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3480-X.