Moxo people

|

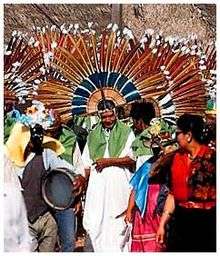

Moxeno chief at a festival in Bolivia | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (20,805 (2000)[1]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Ignaciano, Spanish[1] | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Trinitario |

The Moxos, also known as Moxeños or the Mojos, are an indigenous people of Bolivia. They lived in south central Beni Department,[1] living around the head-waters of the Madeira River in northern Bolivia, particularly on both banks of the Mamore River.

The Moxo were traditionally hunter-gatherers, as well as farmers and pastoralists.[1] They submitted to Inca domination, but in 1564 repulsed the Spaniards. A century later, however, the Jesuit missionaries contacted the Moxos, and the Moxos became Roman Catholic. They numbered some 30,000 in the first decade of the 20th century. Moxeño ethnic identification derives from the combination of different pre-existing ethnic groups in this mission environment, and includes peoples associated with several different missions: Mojeño-Trinitarios (Trinidad mission), Mojeño-Loretanos (Loreto mission), Mojeño-Javerianos, and Mojeño-Ignacianos (San Ignacio de Moxos mission).[2] Many Moxos are affiliated with the Central de Pueblos Indígenas del Beni and/or the Central de Pueblos Étnicos Mojeños del Beni.[2]

Language

Moxo people speak the Ignaciano language, which is a Southern Maipuran language, belonging to the Arawakan language family. The language is used in daily life and taught in beginning primary school grades. A dictionary in Moxo has been published, and the New Testament was translated into the language in 1980.[1]

Name

They are also known as Mojos or Mojeños.

History

Moxos Before the Jesuits

The first Jesuits in Moxos encountered a developed, ancient civilization. Thousands and thousands of artificial hills up to 60 feet high dotted the landscape, along with hundreds of artificial rectangular ponds up to three feet deep, all part of a system of cultivation and irrigation. The people used the built-up high ground for farming and dug canals to unite ponds and rivers that caught water in this flood-prone region.

All these architectural and structural masterpieces can be attributed to the ancestors of the present-day Moxeños, who include the Arawak, the most extensive ethnic group in the area. The Moxos language belongs to a language family called Arawakan. The Arawak have always been famous architects, and indeed the great hydraulic works (dated to ca. 250 CE) of their ancient empire is located in the territory of Moxos. Many other ancient nations and language families survive in modern-day ethnic groups, including the Kayuvava, Itionama, and Movima and the Guarayo of the Guaraní family.

Even today one speaks of the "Amazonian cultures" as a block, despite the differences between the various peoples. The Amazonian cosmos includes a tripartite world: the sky above, the earth here, and the underworld below. These cultures believe that the earth is controlled by a father creator, in collaboration with created spirits or dueños, masters, of places or things and with ancestors who help to maintain justice and balance. Slipping from the norm brings about a spiritual sickness that is cured by a communal search for the cause and by a variety of religious rituals, including prayers and natural remedies. In Moxos the principal dueños are the spirits of the jungle (connected with the tiger) and of the water (connected with the rainbow). Many rich dances renew the life of the community and the universe.

Jesuit mission era

Jesuit priests arriving from Santa Cruz de la Sierra began evangelizing native peoples of the region in the 1670s. They set up a series of missions near the Mamoré River for this purpose beginning with Loreto. The principal mission was established at Trinidad in 1686.[3]

The Jesuit missionaries who first encountered the Moxeños found a people with a strong belief in God as father and creator. The Jesuits accepted in their catechism the names the indigenous peoples gave to God in their own languages, trying to embrace all aspects of the culture not contrary to Christian faith or custom.[4]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ignaciano." Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- 1 2 Molina Argandoña, Wilder.; Cynthia. Vargas Melgar; Pablo. Soruco Claure (2008). Estado, identidades territoriales y autonomías en la región amazónica de Bolivia. La Paz: PIEB. p. 93. ISBN 9789995432249.

- ↑ Gott, Richard (1993). Land without evil : utopian journeys across the South American watershed. London; New York: Verso. p. 225. ISBN 9780860913986.

- ↑ http://www.companysj.com/v153/returntosanignacio.html

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Mehináku material culture, National Museum of the American Indian

- Moxos Indians at the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia.

- "The Amazon and Madeira Rivers: Sketches and Descriptions from the Note-Book of an Explorer" is a book from 1875 that has a chapter about the Moxo people.

Coordinates: 15°40′01″S 65°55′01″W / 15.6670°S 65.9170°W