Mount Independence (Vermont)

Mount Independence on Lake Champlain in Orwell, Vermont, was the site of extensive fortifications built during the American Revolutionary War by the American army to stop a British invasion. Construction began in July 1776, following the American defeat in Canada, and continued through the winter and spring of 1777. After the American retreat on July 5 and 6, 1777, British and German troops occupied Mount Independence until November 1777.

After the American Revolution, Mount Independence was farm land, used for grazing sheep and cattle. It is now a state historic site, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1972 for its historical significance.

Mount Independence State Historic Site

Mount Independence State Historic Site is a Vermont State Historic Site with a museum and 6 miles (9.7 km) of hiking trails.[1] It has been called the least disturbed major Revolutionary War site in the country.[2]

The Mount Independence Visitor Center is open daily from the end of May through mid-October.[3]

The museum houses artifacts recovered by archaeologists including timbers from the Great Bridge and a cannon weighing 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg) cast in Scotland in 1690 and recovered from the lake by underwater archeologists. There is a short film and talking sculptures of the soldiers.

There are 6 miles (9.7 km) of hiking trails. The 1.6 miles (2.6 km) Baldwin Trail is wheelchair-accessible and passes the sites of the blockhouses, the General Hospital, and soldiers’ huts. Longer trails lead to the location of the star-shaped fort, the Horseshoe Battery, and the Great Battery.

There are history and nature walks, encampments of Revolutionary War re-enactors, activities for children, and lectures by Revolutionary War historians. The Seth Warner-Mount Independence Fife and Drum Corps performs in parades and at civic events. The Mount Independence Coalition[4] supports the efforts of the Vermont State Division for Historic Preservation in protecting and interpreting the site.

Geography

Previously[when?] named Rattlesnake Hill, Mount Independence is located in Orwell, Vermont, on the east side of Lake Champlain opposite Ticonderoga, New York, and historic Fort Ticonderoga. At its narrowest, the lake is a quarter mile wide between Mount Independence and Ticonderoga.

Mount Independence is slightly more than a 1.25 miles (2.01 km) in length and less than .75 miles (1.21 km) at its widest. Precipitous cliffs rise from the lake on the west and from East Creek to the east and the low land to the southeast. At its height, the Mount rises about 200 feet (61 m) above lake level. The point juts into the lake nearly due north.[5]

History

Pre-European contact

Mount Independence was important to Native Americans as a source of high quality blue/black chert used for making tools and projectile points. Mount Independence chert was traded across the Northeast. East Creek and the wetlands of the East Creek valley were a rich source of fish, waterfowl, freshwater mussels, beaver, deer, and other animals.[6]

American Revolution

Origins of the American fort

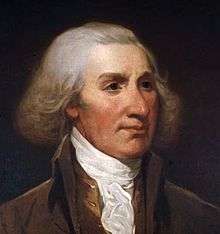

The decision to fortify Mount Independence was made at Fort Crown Point on July 7, 1776, by a Council of War presided over by Northern Department Commander and Major General Philip Schuyler. Less than a week earlier, an American army had returned after a disastrous ten-month invasion of Canada. Morale was low, and the defeated army was ravaged by smallpox.[7]

In a letter, Schuyler told commander in chief George Washington, the peninsula opposite Ticonderoga was “so remarkably strong as to require little labour [sic] to make it tenable against a vast superiority of force, and fully to answer the purpose of preventing the enemy from penetrating into the country south of it.”[8]

Twenty-one field officers objected to the move from Crown Point to Mount Independence, but on July 11 work began on the new site under the direction of military engineer Jeduthan Baldwin of Brookfield, Massachusetts. Within the week, much of the army relocated to Ticonderoga while men labored on Mount Independence to clear the forest and build huts and barracks.[9]

The peninsula gained its new name on Sunday, July 28, 1776, after Colonel Arthur St. Clair of Pennsylvania read the Declaration of Independence to assembled troops.

Fortifications

Mount Independence is a naturally strong defensive position. Unlike Fort Ticonderoga, which dominated the portage from Lake George to Lake Champlain but was open to attack from the north, Mount Independence presented a formidable obstacle to an invader from Canada.

At the height of the American fortification of Mount Independence in the late fall of 1776, the site was occupied by three brigades of New England troops or more than six thousand men, which were reinforced by temporary militia from Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and the New Hampshire Grants (the territory that was to become Vermont). Numerous huts and barracks housed these troops.

An extensive breastwork with a battery of 28 cannons was built at the northern point of the peninsula. Above that position was the Citadel or Horseshoe battery. A star-shaped picket fort was later constructed on the height of land.

A .25 miles (0.40 km) floating bridge of logs covered with planks connected Mount Independence and Ticonderoga. A wider and more permanent bridge, referred to as the Great Bridge, had been designed by Jeduthan Baldwin and was nearing completion at the time the American army abandoned the post in July 1777.

A 250 feet (76 m)-long by 25 feet (7.6 m)-wide two-story hospital was under construction in the southwest. There were storehouses, workshops, and a gunpowder laboratory, and a powder magazine.[10]

In the late spring of 1777, batteries designed by Polish military engineer Thaddeus Kościuszko were constructed on the southeast side of Mount Independence.

During the four-month British and German occupation five blockhouses were begun to defend the east side against attack by land.

Summer and fall 1776

During the summer and fall of 1776, troops on Mount Independence labored to prepare for a British invasion from Canada. At the same time on the west side of Lake Champlain, fortifications were built to the north of old Fort Ticonderoga. In Skenesborough, today’s Whitehall, New York, a fleet of gunboats and row galleys was constructed to defend the lake. Masts were lowered into place at Mount Independence where a rocky outcropping drops sharply to the water. Vessels were also rigged and armed with cannon at the Mount.[11]

By the end of October 1776, there were more than 13,000 men defending the fortifications at Mount Independence and Ticonderoga, making the location one of the largest population centers in the new country.

The troops at Mount Independence and Ticonderoga were commanded by Major General Horatio Gates, who had served as adjutant general of the Continental Army under George Washington. Gates reported to Northern Department commander Philip Schuyler, who remained in Albany, New York. The relationship between the two men was strained and worsened during the following winter and spring. Brigadier General Benedict Arnold commanded a brigade quartered on Mount Independence before Gates gave him the command of the Lake Champlain fleet.

On October 11, 1776, in a day-long battle off Valcour Island in the northern lake, the outgunned American fleet was crippled but managed to escape. However, over the next two days, most of the vessels were destroyed. British forces under Governor General Guy Carleton occupied Fort Crown Point.[12]

Expecting an attack momentarily, the troops at the American forts prepared for battle while messengers carried orders calling for militia and supplies. “Every one [sic] exerts himself to the utmost, for an approaching battle – our works go on day and night without cessation,” wrote one observer.[13]

On October 28, after days of facing headwinds, British vessels approached the American forts. John Trumbull, the future artist of the American Revolution but a young staff officer at the time, described the scene in his autobiography. “The whole summit of cleared land, on both sides of the lake,was crowned with redoubts and batteries, all manned with a splendid show of artillery and flags. The number of our troops under arms that day (principally however militia) exceeded thirteen thousand.” The British boats retreated at sunset and within a few days all the forces at Crown Point had retired to Canada.[14][15]

Winter 1776–1777

Colonel (and beginning in February 1777, Brigadier General) Anthony Wayne of Pennsylvania commanded at Mount Independence and Ticonderoga during the winter of 1776–1777. The number of men at the forts declined to fewer than 3000 in December and by mid-February under 1200.[16]

There were ambitious construction plans for the winter, but in fact survival was a challenge. Men cleared the Mount for firewood and often destroyed unoccupied huts and defensive barriers for fuel. Dysentery was widespread in the early winter and was followed by what Dr. Ebenezer Elmer, who was stationed on Mount Independence, termed “inflammatory disorders of a very complex nature.”[17]

Rations were inadequate. Wayne told the Pennsylvania Council of Safety that the men lacked “every necessary except flour and bad beef.”[18] To maintain discipline, he often ordered the troops to shave and to powder their hair before marching for hours upon the frozen lake.

As spring approached, Wayne continued to request men and supplies, writing to Major General Schuyler, “I must beg, sir, that you would once more endeavor to rouse the public officers in those States from their shameful lethargy before it be too late. I do assure you there is not one moment to spare in bringing in troops and necessary supplies.”[19]

Spring 1777

The pace of work increased in late March with the return of engineer Jeduthan Baldwin. The Great Bridge connecting Mount Independence and Ticonderoga was the first of many projects. Caissons – log cabin-like structures – were begun on the ice and then dragged into holes cut in the frozen surface. Later, the caissons were started close to shore and then floated into place where work continued. Eventually 22 caissons stabilized with stone ballast rose 10 feet (3.0 m) above the water.[20]

Mount Independence and Ticonderoga had a series of commanders during the spring, but finally on June 12 Major General Arthur St. Clair of Pennsylvania took charge. In mid June 1777, an American army of only 2000 healthy enlisted men defended fortifications that stretched 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from the batteries on the southeast of Mount Independence, across Lake Champlain to numerous redoubts on the flats north of old Fort Ticonderoga, the extensive French Lines, and a fort built on the high ground called Mount Hope. St. Clair was to write later, “Had every man I had, been disposed in single file on the different works and along the lines of defence [sic], they would have been scarcely within the reach of each other’s voices.”[21]

When he returned to overall command in the Northern Department in early June, General Schuyler considered abandoning the Ticonderoga side of the lake where the lines were overextended. After a Council of General Officers on June 20, work intensified on Mount Independence. Cannon and supplies were also moved to the Mount in preparation to withdrawing from Ticonderoga.[22]

By the end of June the Americans were certain that the British were advancing in force. In fact, Lieutenant General John Burgoyne had 8000 British and German troops and 138 cannon for the attack on the forts.

On July 2, the American position on the Ticonderoga side of the lake began to crumble as the British mounted cannon on the high ground to the north facing the American lines. Fighting for the British, German troops from the Duchy of Brunswick under command of Major General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel marched east with a goal of cutting off Mount Independence by seizing the narrow land between East Creek and Lake Champlain.

On July 5, British gunners began to construct a battery on Sugar Hill or Mount Defiance, a mountain on the west side of the lake that dominated both Mount Independence and Ticonderoga. Historians continue to debate how decisive the British cannon on Mount Defiance were in the American decision to retreat, but a council of war held that afternoon agreed unanimously to abandon first Ticonderoga and then Mount Independence.[23]

Retreat

The American retreat was scheduled to begin at midnight, July 5–6, and to be conducted in silence without fires or even candlelight. However, Brigadier General Matthias Alexis Roche de Fermoy, a French soldier of fortune, burned his house on Mount Independence, alerting the British to the retreat.[24][25]

Healthy men left Mount Independence just before dawn July 6 on the Mount Independence-Hubbardton Military Road, a path that had been cut through the forest the preceding fall.[26] The sick and wounded made their way to the landing at the southern end of Mount Independence and were taken by boat to Skenesborough along with supplies and cannon. The American flotilla on the narrow lake consisted of six war vessels and about 200 bateaux.[27]

Quickly the British were in pursuit, crossing the floating bridge and seizing the fortifications on Mount Independence. In an old tale that may be apocryphal, four Americans left to guard the bridge were found by a charged cannon, passed out after drinking Madeira.[28]

British vessels broke through the boom and bridge, and followed the American boats to Skenesborough where that afternoon they destroyed the remainder of the fleet and captured the cannon and supplies. Brigadier General Simon Fraser and about 1200 men pursued the Americans on foot. The next morning, July 7, they met at the Battle of Hubbardton. By 18th-century standards it was a British victory, but more recently the battle has been called a “classic example of a rear guard action.” As a result of Hubbardton, Fraser stopped his pursuit of the main American army.[29]

British and German occupation

Following the American withdrawal, Mount Independence was occupied by both British and German troops. For time, wounded American prisoners from the Battle of Hubbardton were treated in the new hospital on the Mount. More than six hundred German troops of the Prince Frederick Regiment defended the fortifications on the southeast side of the Mount where the fort might be attacked from land. Brigadier General Henry Watson Powell had overall command of the forts.

On September 18, Americans surprised Ticonderoga in attack that is known as Brown’s Raid after Colonel John Brown of Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Mount Defiance was taken by Vermont Ranger Captain Ebenezer Allen. Two hundred ninety-three British soldiers were captured, and 118 American prisoners were set free. Old Fort Ticonderoga was threatened.[30]

The attack on Mount Independence was commanded by Colonel Samuel Johnson and then by militia brigadier general Jonathan Warner, both of Massachusetts. Shots were exchanged and a surrender note was sent and ignored. One British officer laughed at the American effort. “It is an undenyable [sic] truth that the Mount was never attacked by the Rebels otherwise than by paper,” wrote Lieutenant John Starke, captain of the schooner-of-war Maria.[31]

The Americans withdrew on September 21. On November 8, following Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga, British and German forces took what they could load aboard their vessels; threw other supplies in the lake; burned barracks, houses, and bridges; disabled about 40 cannon; and retreated to Canada.[32]

After the war

It is likely that George Washington visited Mount Independence during the summer 1783 after the fighting had stopped but before the Treaty of Paris was signed. In 1785 Matthew Lyon, future U.S. congressman, salvaged cannon and other scrap iron on the site for his iron forge in Fair Haven, Vermont.

Mount Independence became a stop for early tourists. It is likely that future U.S. presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison visited in their 1791 tour of lakes George and Champlain. Historian and travel writer Benson J. Lossing visited for his 1853 The Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution. He described the Mount as covered with second growth trees except where the parade grounds were.[33]

During the nineteenth century and much of the twentieth century, Mount Independence was farmland, used for grazing sheep and cattle and for maple sugaring. Maple sugaring continues today.

In 1911 Stephen Pell of Fort Ticonderoga purchased 113 acres (46 ha) at the northern end of Mount Independence.[34] Beginning in 1961, the State of Vermont began to purchase parcels of land at the southern end of Mount Independence. Today the Fort Ticonderoga Association and the Vermont Division of Historic Preservation have joint stewardship of the Mount.

In the late 1960s, the Vermont Electric Power Company (VELCO) proposed building a nuclear plant, to be known as Hugh Crossing, in Orwell. The plan called for damming East Creek to make a 1700 acre cooling pond about a 1 mile (1.6 km) from where the creek meets Lake Champlain. Both historical and environmental concerns led to the project’s defeat.[35]

In 1996, the Vermont Division of Historic Preservation opened a Visitor Center and museum at the southern end of the Mount.

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Vermont

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Addison County, Vermont

References

- ↑ Vermont State Historic Site

- ↑ Starbuck, David. The Great Warpath: British Military Sites from Albany to Crown Point University Press of New England (1999), pgs. 124–159; Zeoli, Stephen. Mount Independence: The Enduring Legacy of a Unique Historic Place, Hubbardton, Vt. (2011).

- ↑ Mount Independence Vermont State Historic Site

- ↑ Mount Independence Coalition

- ↑ Williams, John A. “Mount Independence in Time of War, 1776–1783,” Vermont History (April 1967) 2: 61.

- ↑ Peebles, Giovanna M. “Orwell’s East Creek Valley: A Window Into Vermont’s Early Woodland Past,” The Journal of Vermont Archaeology 5 (2004), 1–22.

- ↑ “Minutes of a Council of War,” July 7, 1776, American Archives, Ser. 5, 1: 234.

- ↑ Philip Schuyler to George Washington, July 12, 1776, American Archives, Ser. 5, 1: 232–233.

- ↑ “Remonstrance of Col. Stark and Officers,” July 8, 1776, American Archives, Ser. 5,1: 233–234; Baldwin, Thomas Williams (ed.). The Revolutionary Journal of Col. Jeduthan Baldwin, 1775–1778. Bangor, Maine (1906), 59.

- ↑ Wintersmith, Charles (surveyor). "Plan of Ticonderoga and Mount Independence." (1777).

- ↑ Bellico, Russell P. Sails and Steam in the Mountains: A Maritime and Military History of Lake George and Lake Champlain. Purple Mountain Press, (1992), pg. 139.

- ↑ Bellico, Sails and Steam in the Mountains, 152–159.

- ↑ Beebe, Lewis. “Journal of a Physician on the Expedition Against Canada, 1776," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. (October 1935) pg. 355.

- ↑ Trumbull, John. Autobiography, Reminiscences and Letters, 1756–1841 (New Haven: Wiley and Putnam, 1841), pg. 36.

- ↑ Cubbison, Douglas R. The American Northern Theater Army in 1776: The Ruin and Reconstruction of the Continental Force. McFarland (2010), phs. 180–199.

- ↑ Stillé, Charles J. Major-General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1893).

- ↑ “Journal of Ebenezer Elmer,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society (1848) vol 3, no.1, pgs. 48, 51.

- ↑ Stillé, Major-General Anthony Wayne, pg. 53.

- ↑ Smith, Williams Henry. The St. Clair Papers: The life and public services of Arthur St. Clair. Cincinnati (1882) vol. 1, pg. 387.

- ↑ Baldwin, pgs. 94–95; McLaughlin, Scott Arthur. History Told from the Depths of Lake Champlain: 1992–1993 Fort Ticonderoga–Mount Independence Submerged Cultural Resource Survey, Master of Arts Dissertation, Texas A & M University (May 2000), pgs. 312–336.

- ↑ St. Clair, Arthur; United States House of Representatives. Narrative of the Manner in which the Campaign Against the Indians, in the Year One Thousand Seven Hundred and Ninety Was Conducted, Under the Command of Major General St. Clair. Philadelphia (1812), 244–245.

- ↑ Proceedings of the General Court Martial, held at White Plains in the state of New-York by order of his Excellency General Washington for the Trial of Major General St. Clair, August 25, 1778, New-York Historical Society Collections vol. 13 (1880), 24–25.

- ↑ Trial Maj. Gen. St. Clair, 33–34; Luzader, John F. Saratoga: A Military History of the Decisive Campaign of the American Revolution. Savas Beatie (2008), 55; Cubbison, Douglas R.. Burgoyne and the Saratoga Campaign: His Papers. Arthur H. Clark Company (2012), 56.

- ↑ Trial Maj. Gen. St. Clair, 81.

- ↑ Ketchum, Richard M. Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War. Henry Holt and Company (1999), pgs. 172–184.

- ↑ Wheeler, Joseph L. and Mabel A. The Mount Independence-Hubbardton 1776 Military Road. Benson, Vt. (1968).

- ↑ Cubbison, Douglas R. Burgoyne and the Saratoga Campaign; His Papers. Arthur H. Clark Company (1012), pg. 63.

- ↑ Duling, Ennis. “Thomas Anburey at the Battle of Hubbardton: How a Fraudulent Source Misled Historians,” Vermont History. Winter/Spring (2010), 2, 11.

- ↑ Williams, John. The Battle of Hubbardton: The American Rebels Stem the Tide. Vermont Division for Historic Preservation (1988), pg. 5.

- ↑ "John Brown and the Dash for Ticonderoga." The Bulletin of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum, vol.II, no.1 (Jan 1930).

- ↑ "Col. John Brown's Attack of September, 1777, on Fort Ticonderoga," Bulletin of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum, vol. XI, no. 4 (July 1964), pg. 209.

- ↑ Collections of the Vermont Historical Society. Montpelier (1870), 1: 247–248.

- ↑ Lossing, Benson J. The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution. Harper& Brothers (1860), vol. 1, pgs. 147–148.

- ↑ Fort Ticonderoga

- ↑ Peebles, "Orwell's East Creek Valley," 2–4.

Coordinates: 43°49′35″N 73°22′49″W / 43.82639°N 73.38028°W