Motion camouflage

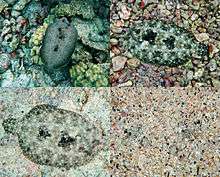

Motion camouflage is a dynamic type of camouflage by which an attacker can approach a target while appearing to remain stationary from the perspective of the target. The attacker chooses its flight path so as to remain on the line between the target and some landmark point. It therefore stays near the landmark point from the target's perspective. The only visible evidence that the attacker is moving is its looming, the change in size as the attacker approaches. First discovered in dragonflies, it has been suggested that missiles could use similar techniques to reduce the time available to targets to respond.

Biological examples

Motion camouflage was discovered in 1995 by M. V. Srinivasan and M. Davey, who were studying mating behavior in hoverflies.[1] The male hoverfly appeared to be using the tracking technique to approach prospective mates.

Motion camouflage has also been observed in high-speed territorial battles between dragonflies, where males of the Australian Emperor Dragonfly,[note 1] Hemianax papuensis, were seen to adjust their flight paths to appear stationary to their rivals.[2][3] Researchers found that 6 of 15 encounters involved motion camouflage.[4]

A 2014 study of falcons of different species (gyrfalcon, saker falcon, and peregrine falcon) using video cameras mounted on their heads or backs showed that these predatory birds used motion camouflage.[5]

Notes

References

- ↑ Srinivasan, M. V. & Davey, M. (1995). "Strategies for active camouflage of motion". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 259 (1354): 19–25. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0004.

- ↑ Hopkin, Michael (June 5, 2003). "Nature News". Dragonfly flight tricks the eye. Nature.com. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ↑ Mizutani, A. K., Chahl, J. S. & Srinivasan, M. V. (June 5, 2003). "Insect behaviour: Motion camouflage in dragonflies". Nature. 65 (423): 604. doi:10.1038/423604a.

- ↑ Glendinning, Paul (27 January 2004). "Motion Camouflage" (PDF). The mathematics of motion camouflage. The Royal Society. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- ↑ Amador Kane, Suzanne; Zamani, Marjon (2014). "Falcons pursue prey using visual motion cues: new perspectives from animal-borne cameras". Journal of Experimental Biology. 217: 225–234. doi:10.1242/jeb.092403.

External links

- Dragonflies prove clever predators

- Steering laws for motion camouflage

- Octave implementation of 2D Motion Camouflage

- Brisbane Insects: Australian Emperor Dragonfly