Monowitz concentration camp

| Monowitz Buna-Werke | |

|---|---|

| Concentration camp | |

|

IG Farben factory within the Auschwitz III camp complex | |

| |

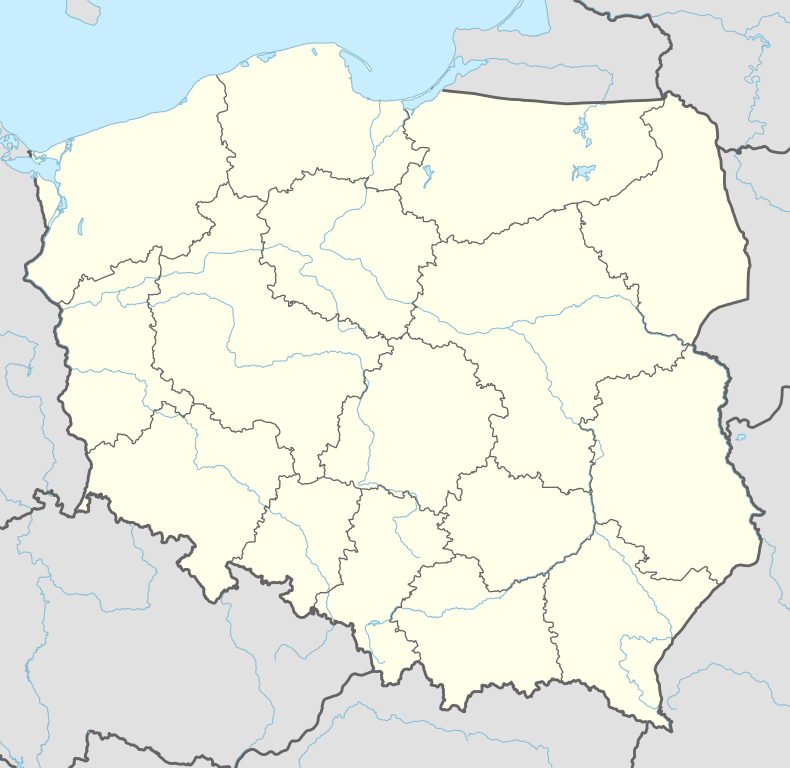

| Coordinates | 50°01′39″N 19°17′17″E / 50.02750°N 19.28806°ECoordinates: 50°01′39″N 19°17′17″E / 50.02750°N 19.28806°E |

| Other names | Monowitz (placename) |

| Known for | Forced labor camp |

| Location | Near Oświęcim, Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany |

| Built by | IG Farben |

| Operated by | Schutzstaffel |

| Original use | Factories for producing synthetic rubber and chemicals including Zyklon B |

| First built | October 1942 |

| Operational | October 1942 - January 1945 |

| Inmates | Mainly Jews |

| Number of inmates | Around 12,000 |

| Liberated by | Red Army on January 27, 1945.[1] |

| Notable inmates | Primo Levi, Victor Perez, Elie Wiesel |

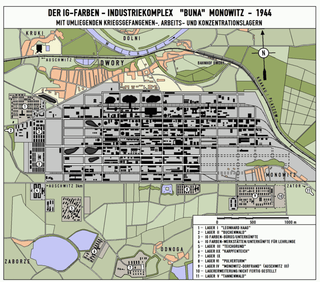

Monowitz (also called Monowitz-Buna or Auschwitz III) was initially established as a subcamp of Nazi Germany's Auschwitz concentration camp. It was one of the three main camps in the Auschwitz concentration camp system, with an additional 45 subcamps in the surrounding area. It was named after the village of Monowice (German: Monowitz) upon which it was built and was located in the annexed portion of Poland. The SS established the camp in October 1942 at the behest of I.G. Farben executives to provide slave labor for their Buna Werke (Buna Works) industrial complex. The name Buna was derived from the butadiene-based synthetic rubber and the chemical symbol for sodium (Na), a process of synthetic rubber production developed in Germany. Various other German industrial enterprises built factories with their own subcamps, such as Siemens-Schuckert's Bobrek subcamp, close to Monowitz in order to profit from the use of slave labor. The German armaments manufacturer Krupp, headed by SS member Alfried Krupp, also built their own manufacturing facilities near Monowitz.[2]

Monowitz was built as an Arbeitslager (workcamp); it also contained an "Arbeitsausbildungslager" (Labor Education Camp) for non-Jewish prisoners perceived not up to par with German work standards. It held approximately 12,000 prisoners, the great majority of whom were Jewish, in addition to non-Jewish criminals and political prisoners. Prisoners from Monowitz were leased out by the SS to IG Farben to labor at the Buna Werke, a collection of chemical factories including those used to manufacture Buna (synthetic rubber) and synthetic oil. The SS charged IG Farben three Reichsmarks (RM) per day for unskilled workers, four (RM) per hour for skilled workers, and one and one-half (RM) for children.

Primo Levi, author of Survival in Auschwitz' survived Monowitz, and Elie Wiesel, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book "Night", was a teenage inmate at Monowitz along with his father. The life expectancy of Jewish workers at Buna Werke was three to four months; for those working in the outlying mines, only one month. Those deemed unfit for work were gassed at Birkenau, phrased as sent "to Birkenau" (nach Birkenau), according to a euphemism used in I.G. Farben record books.[3][4][5]

In November 1943, the SS declared that the Auschwitz II (Birkenau) and Auschwitz III (Monowitz) camps would become separate concentration camps. SS Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Heinrich Schwarz was commandant of Monowitz from November 1943 to January 1945.

History

The creation of the camp was a result of an initiative by the German chemical company IG Farben to build the third largest plant to produce synthetic rubber and liquid fuels.[6] The camp was supposed to be located in Silesia, out of range of Allied bombers. Among the sites proposed between December 1940 and January 1942 the chosen location was the flat land between the eastern part of Oświęcim and the villages of Dwory and Monowice, justified by good geological conditions, access to transport routes, water supply, and the availability of raw materials such as: coal from mines in Libiąż, Jawiszowice, and Jaworzno, limestone from Krzeszowice, and salt from Wieliczka. However, the primary reason for building the industrial complex in that location was the immediate access to the slave work-force from the nearby Auschwitz camps.

IG Farben made the preparations and reached an agreement with the Nazis between February and April 1941. The company bought the land from the treasury for a low price, after it had been seized from Polish owners without compensation and their houses were vacated and demolished. Meanwhile, German authorities removed Jews from their homes in Oświęcim and placed them in Sosnowiec or Chrzanów and sold their homes to IG Farben as housing for company employees brought from Germany. This also happened to some local Polish residents. The IG Farben officials came to an agreement with the concentration camp commandant to hire prisoners at a rate of 3 to 4 marks per day for labor of auxiliary and skilled labor workers.

Trucks began bringing in the first KL prisoners to work at the plant's construction site in mid-April 1941. Starting in May the workers had to walk 6 to 7 km from the camp to the factory site. At the end of July, with the laborers numbering over a thousand, they began taking the train to Dwory station. Their work included leveling the ground, digging drainage ditches, laying cables, and building roads.

The prisoners returned to the construction site in May 1942 and worked there until July 21, when an outbreak of typhus in the main camp and Birkenau stopped their trips to work. Worried over losing the laborers, factory management decided to turn the barracks camp being built in Monowice for civilians over to the SS, to house prisoners. Because of delays in the supply of barbed wire there were several postponements in opening the camp. The first prisoners arrived on October 26 and by early November there were approximately two thousand prisoners.

Buna Werke

The new Buna Werke or Monowitz Buna-Werke factory was located on the outskirts of Oświęcim. The plant construction was commissioned by the Italian State interested in importing nitrile rubber (Buna-N) from IG Farben after the collapse of its own synthetic oil production. The 29 page-long contract signed by the Confederazione Fascista degli Industriali and printed on 2 March 1942 secured the arrival of 8,636 workers from Italy tasked with erecting the installations with the investment of 700 million Reichsmarks by IG Farben (Farben was the producer of nearly all explosives for the German army, with its subsidiary also producing Zyklon-B).[7] The synthetic rubber was to be made virtually for free in occupied Poland using slave labor from among prisoners of Auschwitz, and raw materials from the formerly Polish coalfields. The Buna factory had a workforce of an estimated 80,000 slave laborers by 1944.[8]

According to Joseph Borkin in his book entitled The Crimes and Punishment of IG Farben, IG Farben was the majority financier for Auschwitz III, a camp that contained a production site for production of Buna rubber.[9] Borkin wrote, wrongly, that an Italian Jewish chemist, Primo Levi, was one of the upper level specialists at the Buna plant, and was able to keep some prisoners alive with the assistance of his colleagues, allegedly not producing Buna rubber at a viable production rate.[10][11] In fact Levi was only an inmate there who, in the last two months of his captivity, was sent to a chemical lab due to his former studies as a chemist. Buna Rubber was named by BASF A.G., and through 1988 Buna was a remaining trade name of nitrile rubber held by BASF.

Auschwitz III concentration camp

By 1942 the new labour camp complex occupied about half of its projected area, the expansion was for the most part finished in the summer of 1943. The last 4 barracks were built a year later. The labor camp's population grew from 3,500 in December 1942 to over 6,000 by the first half of 1943. By July 1944 the prisoner population was over 11,000, most of whom were Jews. Despite the growing death-rate from slave labor, starvation, executions or other forms of murder, the demand for labor was growing, and more prisoners were brought in. Because the factory management insisted on removing sick and exhausted prisoners from Monowice, people incapable of continuing their work were murdered.(Reference?) The company argued that they had not spent large amounts of money building barracks for prisoners unfit to work. (Reference?)

On February 10, 1943 SS-Obersturmbannführer Gerhard Maurer, responsible for employment of concentration camp prisoners went to Oświęcim, he promised IG Farben the arrival of another thousand prisoners, in exchange for the incapable factory workers. More than 10,000 prisoners were victims of the selection during the period in which the camp operated. Taken to the main camp's hospital, most victims were killed by a lethal injection of phenol to the heart.(Reference?) Some were sent to Birkenau where they were liquidated after “re-selection” in the Bllf prison hospital or in most cases murdered in the gas chambers.(Reference?) More than 1,600 other prisoners died in the hospital at Monowice, and many were shot at the construction site or hanged at the camp.(Reference) Summing up all figures, an estimated total number of about 10,000 Auschwitz concentration camp prisoners lost their lives because of working for IG Farben.

Death rate

The total number of victims at Auschwitz III cannot be blamed solely on the murderous conditions that were nearly the same in all Auschwitz camps and sub-camps. The barracks were overcrowded like the ones in Birkenau, however the ones in Monowice had windows and heating during the winter when needed. “Buna-Suppe” a watery soup was served as a minimal supplement, along with the extremely low food rations. It can reasonably be inferred that the reason for the high death-rates in the Monowice camp is because factory management wanted to maintain a high work rate, and tried to do so by giving directions to the foremen. The foremen were in charge of laborers and constantly demanded that the capos and SS men enforce higher productivity of the prisoners, by beating them. The factory's management approved such methods. In reports sent from Monowice to the corporate headquarters in Frankfurt am Main, Maximilian Faust, an engineer in charge of construction stated in these reports that the only way to keep the prisoners' labor productivity at a satisfactory level was through the use of violence and corporal punishment. While declaring his own opposition to “flogging and mistreating prisoners to death,” Faust nevertheless added that “achieving the appropriate productivity is out of the question without the stick.”

Prisoners worked more slowly than the German construction workers, even with being beaten. This was a source of anger and dissatisfaction to factory management, and led to repeated requests that camp authorities increase the numbers of SS men and energetic capos to supervise the prisoners. A group of specially chosen German common criminal capos were sent to Monowice. When these steps seemed to fail, IG Farben officials suggested the introduction of rudimentary piecework system and a motivational scheme including the right to wear watches, have longer hair (rejected in practice), the payment of scrip that could be used in the camp canteen (which offered cigarettes and other low-value trifles for sale), and free visits to the camp bordello (which opened in the Monowice camp in 1943).

These steps hardly had an effect on prisoner productivity. In December 1944, at conferences in Katowice, it was brought to attention that the real cause of prisoners' low productivity: the motivational system was characterized as ineffective and the capos as “good,” but it was admitted that the prisoners worked slowly simply because they were hungry.

Overseers

To a large degree, the SS men from the garrison in Monowice were responsible for the conditions that prevailed in the camp. SS-Obersturmführer Vinzenz Schöttl held the post of Lagerführer during the period when Monowice functioned as one of the many Auschwitz sub-camps.[12] In November 1943, after the reorganization of the administrative system and the division of Auschwitz into three quasi-autonomous components, the camp in Monowice received a commandant of its own. This was SS-Hauptsturmführer Heinrich Schwarz, who until then had been the head of the labor department and Lagerführer in the main camp. At Monowice, he was given authority over the Jawischowitz, Neu-Dachs in Jaworzno, Fürstengrube, Janinagrube in Libiąż, Golleschau in Goleszów, Eintrachthütte in Świętochłowice, Sosnowitz, Lagischa, and Brünn (in Bohemia) sub-camps. Later, the directors of new sub-camps opened at industrial facilities in Silesia and Bohemia answered to him. Rudolf Wilhelm Buchholz and Richard Stolten were SS men there. Also present were: Dr. Bruno Kitt; from December 1942 to January 1943 or March 1943, SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr. Hellmuth Vetter; from March 1943 to October 20, 1943, SS-Obersturmführer Dr. Friedrich Entress. From October 1943 to November 1943, there followed SS-Obersturmführer Dr. Werner Rohde; from November 1943 to September 1944, SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr. Horst Fischer; and finally, from September 1944 to January 1945, SS-Obersturmführer Dr. Hans Wilhelm König.[12]

Bernhard Rakers was Kommandoführer in 1943, then roll-call leader in Buna/Monowitz concentration camp, sentenced to life in prison in 1953 for murder of prisoners (pardoned in 1971, died in 1980).[12]

Fritz Löhner-Beda (prisoner number 68561) was a popular song lyricist who was murdered in Monowitz-Buna at the behest of an IG Farben executive, as his friend Raymond van den Straaten testified at the Nuremberg trial of 24 IG Farben executives:

One day, two Buna inmates, Dr. Raymond van den Straaten and Dr. Fritz Löhner-Beda, were going about their work when a party of visiting IG Farben dignitaries passed by. One of the directors pointed to Dr. Löhner-Beda and said to his SS companion, ‘This Jewish swine could work a little faster.’ Another director then chanced the remark, ‘If they can’t work, let them perish in the gas chamber.’ After the inspection was over, Dr. Löhner-Beda was pulled out of the work party and was beaten and kicked until, a dying man, he was left in the arms of his inmate friend, to end his life in IG Auschwitz.”[13]

In May 1944, the headquarters of a separate guard battalion (SS-Totenkopfsturmbann KL Auschwitz III) was established in Monowice. It consisted of seven companies, which were on duty in the following sub-camps:

- 1 Company – Monowitz,

- 2 Company – Golleschau in Goleszów, and Jawischowitz in Jawiszowice,

- 3 Company – Bobrek, Fürstengrube, Günthergrube, and Janinagrube in Libiąż,

- 4 Company – Neu-Dachs in Jaworzno,

- 5 Company – Eintrachthütte, Lagischa, Laurahütte, and Sosnowitz II in Sosnowiec,

- 6 Company – Gleiwitz I, II and III in Gliwice,

- 7 Company – Blechhammer in Blachownia.

In September 1944, a total of 1,315 SS men served in these companies. The 439 of them who made up 1 Company were stationed at Monowice, and included not only guards but also the staff of the offices and stores that saw to the needs of the remaining sub-camps.

In January 1945, the majority of the prisoners were evacuated and sent on a death march to Gliwice, and then carried by train to the Buchenwald and Mauthausen camps. Prisoners at the camp in Monowice included the Nobel Peace-Prize winner Elie Wiesel, the prominent Italian writer Primo Levi and the film production designer Willy Holt, informs the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum webpage.

Monowitz/Buna-Werke bombed

The Allies bombed the I.G. Farben factories at Monowitz four times, all of them during the last year of the war.

- The first raid was conducted August 20, 1944 by 127 B-17 Flying Fortresses of the 15th U.S. Army Air Force based in Foggia Italy. The first bombing started at 10:32 p.m. and lasted for 28 minutes. A total of 1,336 500 lb. high explosive bombs were dropped from an altitude of between 26,000 and 29,000 feet.

- On September 13, 1944 96 B-24 Liberators bombed Monowitz in an air raid that lasted 13 minutes.

- The third attack occurred on December 18, 1944 by two B-17s and 47 B-24s, 436 500 lb. bombs were dropped.

- The fourth and last attack was on December 26, 1944 by 95 B-24s; a total of 679 500 lb. bombs were dropped.[14][15]

Liberation of the camp

On January 18, 1945, all prisoners in Monowitz whom the Nazis deemed healthy enough to walk were evacuated from the camp and sent on a death march to the Gleiwitz (Gliwice) a subcamp near the Czech border.[1] Victor “Young” Perez (prisoner number 107984) a professional boxer of Jewish heritage from French Tunisia died on the death march on January 22, 1945;[16] Paul Steinberg, who would chronicle his experiences in a 1996 book, was among those on the march.[17] He was later liberated by the American Army at Buchenwald.[18] The remaining prisoners were liberated on January 27, 1945 by the Red Army along with others in the Auschwitz camp complex, among them was the renowned writer Primo Levi.[19]

Beginning mid-February 1945 the Red Army shipped much equipment and machinery from the Buna Werke factory to western Siberia using captured German specialists who helped dismantle it bit by bit.[20] However, many of the original buildings remained, and the chemical industry was rebuilt on the site after the war. At the grounds of the former factory are the two Polish companies: Chemoservis-Dwory S.A., which produces metal structures, parts, metal building elements, tanks and reservoirs etc., and Synthos Dwory Sp. a subsidiary of the Synthos S.A. Group which manufactures synthetic rubbers, latex and polystyrene among other chemical products. Both are based in Oświęcim. Extant structures and visible remains of the Monowitz camp itself include the original camp smithy, part of the prisoner kitchen building, a ruined building of the SS Barracks, a large concrete air raid shelter for the SS guard force (type "Salzgitter/Geilenberg"), and small one-man SS air raid shelters (these can also be found on the grounds of the Buna Werke factory, along with larger concrete air raid shelters for the factory workers).

British POW camp

Several hundred meters west of the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp there was a work subcamp, E715, of the main camp (Stalag VIII-B) in Lamsdorf (after November 1943, in Teschen). British and other Commonwealth POWs were held there and the camp was administered by Wehrmacht, not SS. Most of these POWs had been captured in North Africa, initially by Italian troops. After Italy’s change of sides in 1943, the German Army took them to prisoner of war camps in Silesia and finally to Auschwitz. The first 200 British POWs reached Auschwitz in early September 1943. In winter 1943/44, about 1,400 British POWs were interned in E715. In February and March 1944, around 800 of them were moved to Blechhammer and Heydebreck. After that time, the number of British prisoners of war in Auschwitz remained constant, at around 600.

The regime for the British POWs in Auschwitz was not significantly different from those elsewhere. They received Red Cross parcels. However, one soldier, Corporal Reynolds, who refused to climb girders because it was cold and he did not have appropriate clothing was shot dead on the spot.

The British POWs could see what was going on in the Monowitz concentration camp; they could hear shots at night and see the bodies of men who had been hanged. At the Monowitz construction site the POWs came in contact with the concentration camp inmates.

As the Red Army was approaching Auschwitz in January 1945, the Wehrmacht closed E715 on January 21, 1945, and made the British prisoners of war march through Poland and Czechoslovakia in the direction of Bavaria. In April 1945, the U.S. Army freed the British prisoners of war from Auschwitz in Stalag VII A in Moosburg.[21][22]

In popular culture

- In Foyle's War series eight, episode 1 ("High Castle"), Foyle tours Monowitz as part of his investigation of the murder of a London University professor, who as a translator for the Nuremberg Trials becomes involved with an American industrialist who owns a petroleum company, and a German war criminal named Linz, who also turns up dead, in his cell. Linz's firm, IG Farben, had hired from the SS forced laborers incarcerated at Moskowitz.

- Martin Amis's novel The Zone of Interest is set during construction of the Buna Werke and Monowitz.

See also

- Charles Coward

- Auschwitz concentration camp

- List of concentration camps of Nazi Germany

- If This Is a Man

- Primo Levi

- Arthur Dodd (Auschwitz survivor)

References

- 1 2 "Timeline for I.G. Farben and the Buna/Monowitz Concentration Camp". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Synthetic Rubber: A Project That Had to Succeed (Contributions in Economics and Economic History) by Vernon Herbert & Attilio Bisio.Publisher: Greenwood Press (December 11, 1985) Language: English ISBN 0313246343 ISBN 978-0313246340

- ↑ Anatomy of the Auschwitz death camp By Yisrael Gutman, Michael Berenbaum Publisher: Indiana University Press (April 1, 1998) Language: English ISBN 025320884X ISBN 978-0253208842

- ↑ Night by Elie Wiesel Publisher: Bantam (March 1, 1982) Language: English ISBN 0553272535 ISBN 978-0553272536

- ↑ The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide by Robert Jay Lifton Publisher: Basic Books (August 2000) Language: English ISBN 0465049052 ISBN 978-0465049059

- ↑ "Auschwitz III (Monowitz)". Krakow 3D. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ John F. Ptak (September 23, 2008). "Hermann Goering, IG Farben and Zyklon-B". From The Nuremberg Interviews (Knopf, 2004) by Leon Goldensohn. Ptak Science Books. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ John F. Ptak (September 23, 2008). "Distinguishing Oświęcim (town), Auschwitz I, II, & III, and the Buna Werke". From the "Pamphlet Collection" of the Library of Congress. Ptak Science Books. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ IG Farben#World War II overview

- ↑ Borkin, Joseph (June 1, 1978). The Crime and Punishment of I.G. Farben. Free Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0029046302.

- ↑ I.G. Farbenindustrie AG Trial, a.k.a. The United States of America vs. Carl Krauch, et al.

- 1 2 3 Buna/Monowitz Concentration Camp Organizational Structure and Commandant’s Office at Wollheim Memorial.de

- ↑ Dein ist mein ganzes Herz (Fritz Löhner-Beda) by Günther Schwarberg (2000) ISBN 3882437154

- ↑ Neufeld, Michael J.; Berenbaum, Michael, eds. (2000). The Bombing of Auschwitz: Should the Allies Have Attempted It? (First ed.). New York/Washington, D.C.: St. Martin's Press and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 9780312198381. OCLC 41368222.

- ↑ Extracts from the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, summarizing 15th Air Force bombing attacks in August and September 1944 on Oswiecim (Auschwitz)

- ↑ "Victor "Young" Perez (1911–1945)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Steinberg, Paul (2000). Chroniques d’ailleurs. New York, New York: Metropolitan Books. p. 192. ISBN 0805060642.

- ↑ Quatre boules de cuir ou l’étrange destin de Young Perez, champion du monde de boxe by André Nahum: Publisher: Bibliophane (April 24, 2002) ISBN 2869700601 ISBN 978-2869700604 .

- ↑ Kakutani, Michiko (12 December 1989). "Books of The Times; Primo Levi and the Ghosts of Auschwitz". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt am Main (2014). "Monowitz / Monowice: factory and camp grounds after 1945". The Norbert Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt am Main (2014). "E715 – Camp for British Prisoners of War". The Norbert Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ↑ Simon Round. "Revealed: the British troops imprisoned at Auschwitz". Jewish Chronicle Online.

Bibliography

- The Crime and Punishment of I.G. Farben by Joseph Borkin (New York: Free Press, 1978). Language: English ISBN 0671827553 ISBN 978-0671827557

- Industry and Ideology Peter Hayes .Publisher: Cambridge University Press; 2 edition (November 13, 2000) Language: English ISBN 052178638X ISBN 978-0521786386

- If this is a man, Primo Levi

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Auschwitz III (Monowitz). |

- Auschwitz Forgotten Evidence Shows clips of Monowitz bombing.

- Holocaust History.Org

- Search "Monowitz" in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Website

- Wollheim Memorial

- Dwory S.A. at Wikimapia

- Guide to the Concentration Camps Collection at the Leo Baeck Institute, New York, NY. Contains materials on survivors of Buna-Monowitz (Auschwitz III).