Mitre

The mitre (/ˈmaɪtər/; Greek: μίτρα, "headband" or "turban"), also spelled miter (see spelling differences), is a type of headgear now known as the traditional, ceremonial head-dress of bishops and certain abbots in traditional Christianity. Mitres are worn in the Orthodox Church, Roman Catholic Church, as well as in the Anglican Communion, some Lutheran churches, and also bishops and certain other clergy in the Eastern Catholic Churches and the Oriental Orthodox Churches. The Metropolitan of the Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church also wears a mitre during important ceremonies such as the Episcopal Consecration.

Origin

Etymology

The word μίτρα, mítra (or, in its Ionic form, μίτρη, mítrē), first appears[1] in Greek and signifies one of several garments: a kind of waist girdle worn under a cuirass, as mentioned in Homer's Iliad; a headband used by women for their hair; and a sort of formal Babylonian head dress, as mentioned by Herodotus (Histories 1.195 and 7.90). The former two meanings have been etymologically connected with the word μίτος, mítos, "thread", but the connection is tenuous at best.

Byzantine empire

The camelaucum (Greek: καμιλαύκιον, kamilafkion), the headdress, that both the mitre and the Papal tiara stem from, was originally a cap used by officials of the Imperial Byzantine court. "The tiara [from which the mitre originates] probably developed from the Phrygian cap, or frigium, a conical cap worn in the Graeco-Roman world. In the 10th century the tiara was pictured on papal coins."[2] Other sources claim the tiara developed the other way around, from the mitre. In the late Empire it developed into the closed type of Imperial crown used by Byzantine Emperors (see illustration of Michael III, 842-867).

Worn by a bishop, the mitre is depicted for the first time in two miniatures of the beginning of the eleventh century. The first written mention of it is found in a Bull of Pope Leo IX in the year 1049. By 1150 the use had spread to bishops throughout the West; by the 14th century the tiara was decorated with three crowns.

Christian clergy

Western Christianity

In its modern form in Western Christianity, the mitre is a tall folding cap, consisting of two similar parts (the front and back) rising to a peak and sewn together at the sides. Two short lappets always hang down from the back.

In the Catholic Church, the right to wear the mitre is confined by Canon law to bishops and to abbots, as it appears in the ceremony of consecration of a bishop and blessing of an abbot. Cardinals are now normally supposed to be bishops (since the time of Pope John XXIII), but even cardinals who are not bishops and who have been given special permission by the pope to decline consecration as bishops may wear the mitre. Other prelates have been granted the use of the mitre by special privilege, but this is no longer done, except in the case of an Ordinary of a Personal Ordinariate (even if he is a priest only). Former distinctions between "mitred abbots" and "non-mitred abbots" have been abolished.

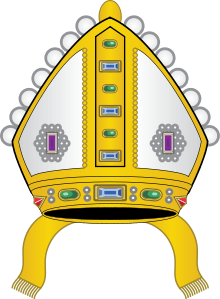

Three types of mitres are worn by Roman Catholic clergy for different occasions:

- The simplex ('simple', referring to the materials used) is made of undecorated white linen or silk and its white lappets traditionally end in red fringes. It is worn most notably at funerals, Lenten time, on Good Friday and by concelebrant bishops at a Mass. Cardinals in the presence of the Pope wear a mitre of white linen damask.

- The auriphrygiata is of plain gold cloth or white silk with gold, silver or coloured embroidered bands; when seen today it is usually worn by bishops when they preside at the celebration of the sacraments.

- The pretiosa ('precious') is decorated with precious stones and gold and worn on the principal Mass on the most solemn Sundays (except in Lent) and feast days. This type of mitre is rarely decorated with precious stones today, and the designs have become more varied, simple and original, often merely being in the liturgical colour of the day.

The proper colour of a mitre is always white, although in liturgical usage white also includes vestments made from gold and silver fabrics. The embroidered bands and other ornaments which adorn a mitre and the lappets may be of other colours and often are. Although coloured mitres are sometimes sold and worn at present, this is probably due to the maker’s or wearer’s lack of awareness of liturgical tradition.

On all occasions, an altar server may wear a shawl-like veil, called a vimpa, around the shoulders when holding the bishop's mitre. The vimpa is used to hold the mitre so as to avoid the possibility of it being soiled by the natural oils in a person's hand as well as symbolically showing that the person does not own the mitre, but merely holds it for the prelate. The person wearing a vimpa is also occasionally referred to as a vimpa. When a vimpa holds the crosier, he holds the crook facing inward, as another sign that the person does not hold the authority of the crosier.

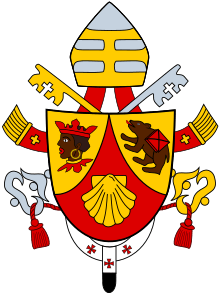

With his inauguration as pope, Benedict XVI broke with tradition and replaced the papal tiara even on his papal coat of arms with a papal mitre (containing still the three levels of 'crowns' representing the powers of the Papacy in a simplified form) and pallium. Prior to Benedict XVI, each pope's coat of arms always contained the image of the papal tiara and St. Peter's crossed keys, even though the tiara had fallen into disuse, especially under popes John Paul I and John Paul II. Pope Paul VI was the last pope to date to begin his papal reign with a formal coronation in June 1963. However, as a sign of the need for greater simplification of the papal rites, as well as the changing nature of the papacy itself, he abandoned the use of his tiara in a dramatic ceremony in Saint Peter's Basilica during the second session of Vatican II in November 1963. However his 1975 Apostolic Constitution made it clear the tiara had not been abolished: in the constitution he made provision for his successor to receive a coronation. Pope John Paul I, however, declined to follow Paul VI's constitution and opted for a simpler papal inauguration, a precedent followed by his three successors. Pope John Paul II's 1996 Apostolic Constitution left open several options by not specifying what sort of ceremony was to be used, other than that some ceremony would be held to inaugurate a new pontificate.

Pope Paul VI donated his tiara (a gift from his former archdiocese of Milan) to the efforts at relieving poverty in the world. Later, Francis Cardinal Spellman of New York received the tiara and took it on tour of the United States to raise funds for the poor. It is on permanent view in the Crypt Church in the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C.

In the Church of England, the mitre fell out of use after the Reformation, but was restored in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a result of the Oxford Movement, and is now worn by most bishops of the Anglican Communion on at least some occasions. The mitre is also worn by bishops in a number of Lutheran churches, for example the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia and the Church of Sweden.[3]

In ecclesiastical heraldry, a mitre was placed above the shield of all persons who were entitled to wear the mitre, including abbots. It substituted for the helm of military arms, but also appeared as a crest placed atop a helmet, as was common in German heraldry.[4] In the Anglican Churches, the mitre is still placed above the arms of bishops instead of the ecclesiastical hat. In the Roman Catholic Church, the use of the mitre above the shield on the personal arms of clergy was suppressed in 1969,[5] and is now found only on some corporate arms, like those of dioceses. Previously, the mitre was often included under the hat,[6] and even in the arms of a cardinal, the mitre was not entirely displaced.[7] In heraldry the mitre is always shown in gold, and the lappets (infulae) are of the same colour. It has been asserted that before the reformation, a distinction was used to be drawn between the mitre of a bishop and an abbot by the omission of the infulae in the abbot's arms. In England and France it was usual to place the mitre of an abbot slightly in profile.[4]

Eastern Christianity

The most typical mitre in the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic churches is based on the closed Imperial crown of the late Byzantine Empire. Therefore, it too is ultimately based on the older καμιλαύκιον although it diverged from the secular headdress at a much later date, after it had already undergone further development. The crown form was not used by bishops until after the fall of Constantinople (1453).

The Eastern mitre is made in the shape of a bulbous crown, completely enclosed, and the material is of brocade, damask or cloth of gold. It may also be embroidered, and is often richly decorated with jewels. There are normally four icons attached to the mitre (often of Christ, the Theotokos, John the Baptist and the Cross), which the bishop may kiss before he puts it on. Eastern mitres are usually gold, but other liturgical colours may be used.

The mitre is topped by a cross, either made out of metal and standing upright, or embroidered in cloth and lying flat on the top. In Greek practice, the mitres of all bishops are topped with a standing cross. The same is true in the Russian tradition. Mitres awarded to priests will have the cross lying flat. Sometimes, instead of the flat cross, the mitre may have an icon on the top.

As an item of Imperial regalia, along with other such items as the sakkos (Imperial dalmatic) and epigonation, the mitre came to signify the temporal authority of bishops (especially that of the Patriarch of Constantinople) within the administration of the Rum millet (i.e., the Christian community) of the Ottoman Empire. The mitre is removed at certain solemn moments during the Divine Liturgy and other services, usually being removed and replaced by the protodeacon.

The use of the mitre is a prerogative of bishops, but it may be awarded to archpriests, protopresbyters and archimandrites. The priestly mitre is not surmounted by a cross, and is awarded at the discretion of a synod of bishops.

Military uniform

.jpg)

During the 18th century (and in a few cases the 19th), soldiers designated as grenadiers in various northern European armies wore a mitre (usually called a "mitre cap") similar in outline to those worn by western bishops. As first adopted in the 1680s this cap had been worn instead of the usual broad-brimmed hat to avoid the headdress being knocked off when the soldier threw a grenade.[8]The hand-grenade in its primitive form had become obsolete by the mid-18th century[9] but grenadiers continued as elite troops in most European armies, usually retaining the mitre cap as a distinction.

Militarily, this headdress came in different styles. The Prussian style had a cone-shaped brass or white-metal front with a cloth rear having lace braiding;[10] the Russian style initially consisted of a tall brass plate atop of a leather cap with a peak at the rear, although the German model was subsequently adopted. The British style—usually simply called a "grenadier cap" instead of a mitre—had a tall cloth front with elaborate regimental embroidery forward of a sloping red back, lined in white.[11] Some German and Russian fusilier regiments also wore a mitre with a smaller brass front-plate.

By the end of the 18th century, due to changes in military fashion, the mitre had generally given way to the bearskin or had been replaced by the standard infantry tricorn or bicorn. The British Army made this change in 1765 and the Prussian Army in 1790. All Russian grenadiers continued however to wear mitre caps until 1805, even when on active service.[12]

The mitre in its classic metal-fronted 18th century form survived as an item of ceremonial parade dress in the Prussian Leib-Grenadier No 1 and 1st Garde-Regiment zu Fuss regiments, plus the Russian Pavlovskii Regiment, until World War I.

Other uses

The bishop in the board game chess is represented by a stylised Western mitre having Unicode codes 0x2657 (white) and 0x265D (black): ♗♝.

The crowns of the Austrian Empire and Imperial Russia incorporated a mitre of precious metal and jewels into their design. The Austrian Imperial Crown was originally the personal crown of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II and has the form proper to that of a Holy Roman Emperor. At the Roman rite of their Coronation, the Pope placed a mitre on their heads before placing the crown over it. Their empress consorts also received both a mitre and crown on their heads from a cardinal bishop at the same ceremony. The form of the Russian Imperial Crown dates back to the time of Peter the Great’s early attempts to westernise Russia and was probably inspired by the crowns worn by Habsburg emperors of the Holy Roman Empire and possibly also the Orthodox mitre.

Abbesses of certain very ancient abbeys in the West also wore mitres, but of a very different form than that worn by male prelates.

The mitral valve of the human heart, which is located between the left atrium and the left ventricle, is named so because of its similarity in shape to the mitre. Andreas Vesalius, the father of anatomy, noted the striking similarity between the two while performing anatomic dissections in the sixteenth century.[13]

Notes

- ↑ first appears

- ↑ Britannica 2004, tiara

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/386220/mitre

- 1 2

"Ecclesiastical Heraldry". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

"Ecclesiastical Heraldry". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913. - ↑ "Instruction", 1969, n.28.

- ↑ Lartigue, Dictionnaire.

- ↑ von Volborth, Heraldry of the World, p.171, shows the arms of Cardinal Francis Spellman with mitre in 1967, just two years before the 1969 Instruction.

- ↑ W.Y. Carman, page 68 "A Dictionary of Military Uniform," ISBN 0-684-15130-8

- ↑ W.Y. Carman, page 68 "A Dictionary of Military Uniform," ISBN 0-684-15130-8

- ↑ Philip Haythornthwaite, page 13 "Frederick the Great's Army, vol. 2 Infantry ", ISBN 1855321602

- ↑ Stuart Reid, page 24 "King George's Army 1740-93, vol. 1 Infantry," ISBN 1 85532 515 2

- ↑ Philip Haythornthwaite, page 18 "The Russian Army of the Napoleonic Wars (1): Infantry, 1799-1814" ISBN 0-85045-737-8

- ↑ Charles Davis O'Malley, "Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514-1564," (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964).

References

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Mitre". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Mitre". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Noonan, Jr., James-Charles (1996). The Church Visible: The Ceremonial Life and Protocol of the Roman Catholic Church. Viking. p. 191. ISBN 0-670-86745-4.

- Philippi, Dieter (2009). Sammlung Philippi - Kopfbedeckungen in Glaube, Religion und Spiritualität,. St. Benno Verlag, Leipzig. ISBN 978-3-7462-2800-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mitres. |

- Mitres Photographs and descriptions of the different types of mitres

- Episcopal Mitre from Kavsokalyvia, Mount Athos

- Mitre worn by the Archbishop of Esztergom, the Primate of Hungary, at coronations of Kings of Hungary.

- Mitre worn by Pope John Paul I at his papal inauguration Mass. From the National Geographic book Inside the Vatican, 1991.