Mithridates I of Parthia

| Mithridates I | |

|---|---|

| "King of kings of Iran" | |

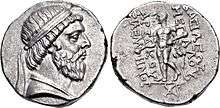

Coin of Mithridates I of Parthia, showing him wearing a beard and a royal diadem on his head | |

| Reign | 165-132 BC |

| Predecessor | Phraates I |

| Successor | Phraates II |

| Born | c. 195 BC |

| Died | 132 BC |

| Dynasty | Arsacid dynasty |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Mithridates or Mithradates I (Parthian: Mihrdat, Persian: مهرداديکم, Mehrdād), (ca. 195 BC – 132 BC) was king of the Parthian Empire from 165 BC to 132 BC, succeeding his brother Phraates I.[1][2] His father was King Phriapatius of Parthia, who died ca. 176 BC). Mithridates I made Parthia into a major political power by expanding the empire to the east, south, and west. During his reign the Parthians took Herat (in 167 BC), Babylonia (in 144 BC), Media (in 141 BC) and Persia (in 139 BC). Because of his many conquests and religious tolerance, he has been compared to other Iranian kings such Cyrus the Great (d. 530 BC), founder of the Achaemenid Empire.[3]

Biography

Mithridates first expanded Parthia's control eastward by defeating King Eucratides of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. This gave Parthia control over Bactria's territory west of the Arius river, the regions of Margiana and Aria (including the city of Herat in 167 BC).

- "The satrapy Turiva and that of Aspionus were taken away from Eucratides by the Parthians." (Strabo XI.11.2[4])

These victories gave Parthia control of the overland trade routes between east and west (the Silk Road and the Persian Royal Road). This control of trade became the foundation of Parthia's wealth and power and was jealously guarded by the Parthians, who attempted to maintain direct control over the lands through which the major trade routes passed.

After defeating the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom in the east, Mithridates then focused on the Seleucid realm. He invaded Media and occupied Ecbatana in 148 or 147 BC; the region had been destabilized by a recent Seleucid suppression of a rebellion there led by Timarchus.[5] This victory was followed by the Parthian conquest of Babylonia in Mesopotamia, where Mithridates had coins minted at Seleucia in 141 BC and held an official investiture ceremony.[6] While Mithridates retired to Hyrcania, his forces subdued the kingdoms of Elymais and Characene and occupied Susa.[6] By this time, Parthian authority extended as far east as the Indus River.[7]

After having gained full control over the recently conquered regions, Mithridates established royal residences at Seleucia, Ecbatana, Ctesiphon and his newly founded city, Mithradatkert (Nisa, Turkmenistan), where the tombs of the Arsacid kings were built and maintained.[8] Ecbatana became the main summertime residence for the Arsacid royalty.[9] It became the site of the royal coronation ceremony and the representational city of the Arsacids, according to Brosius.[10]

The Seleucids were unable to retaliate immediately as general Diodotus Tryphon led a rebellion at the capital, Antioch, in 142 BC.[11] However, by 140 BC Demetrius II Nicator was able to launch a counter-invasion against the Parthians in Mesopotamia. Despite early successes, the Seleucids were defeated and Demetrius himself was captured by Parthian forces and taken to Hyrcania. There Mithridates treated his captive with great hospitality; he even married his daughter Rhodogune of Parthia to Demetrius.[12]

However, Demetrius was restless and twice tried to escape from his exile in Hyrcania on the shores of the Caspian sea, once with the help of his friend Kallimander, who had gone to great lengths to rescue the king: he had traveled incognito through Babylonia and Parthia. When the two friends were captured, the Parthian king did not punish Kallimander but rewarded him for his fidelity to Demetrius. The second time Demetrius was captured when trying to escape, Mithridates humiliated him by giving him a golden set of dice, thus hinting that Demetrius was a restless child who needed toys. It was however for political reasons that the Parthians treated Demetrius II kindly. He was held captive for ten years while Mithridates was consolidating his conquests.

Death

Originally, it was thought that Mithridates was killed in battle near Seleucia, fighting the resurgent Seleucid forces under Antiochus VII Sidetes; brother of Demetrius II Nicator. However, recent evidence suggests that Mithridates became increasingly ill after 138 BC but did not die until 132 BC.

Mithridates I's son, Phraates (132–128 BC), succeeded him on his death as King, and would later avenge his father by invading Media and killing Antiochus VII Sidetes.

Relations with the Greeks

Parthian victories broke the tenuous link with Greeks in the west that had sustained the Hellenistic kingdom of Greco-Bactria, yet Mithridates I actively promoted Hellenism in the areas he controlled and titled himself Philhellene ("friend of the Greeks") on his coins.

Coins

The coins minted during his reign show the first appearance on Parthian coinage of a Greek-style portrait showing the royal diadem, the standard Greek symbol for kingship. Mithradates I resumed the striking of coins, which had been suspended ever since Arsaces II of Parthia (211–191 BC) had been forced to submit to the Seleucid Antiochus III (223–187 BC) in 206 BC.

References

- ↑ "Assar_2005" http://parthian-empire.com/articles/Genealogy-and-Coinage-of-Early-Parthian-Rulers-II.pdf

- ↑ "Assar_2006"

- ↑ "katouzian_2009_41"

- ↑ Strabo 11.11.2

- ↑ Curtis 2007, pp. 10–11; Bivar 1983, p. 33; Garthwaite 2005, p. 76

- 1 2 Curtis 2007, pp. 10–11; Brosius 2006, pp. 86–87; Bivar 1983, p. 34; Garthwaite 2005, p. 76;

- ↑ Garthwaite 2005, p. 76; Bivar 1983, p. 35

- ↑ Brosius 2006, pp. 103, 110–113

- ↑ Kennedy 1996, p. 73; Garthwaite 2005, p. 77

- ↑ "brosius_2006_103"/>

- ↑ Bivar 1983, p. 34

- ↑ Brosius 2006, p. 89; Bivar 1983, p. 35

Sources

- Toumanoff, Cyril (1986). "Arsacids". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. Cyril Toumanoff. pp. 525–546.

| Mithridates I of Parthia Died: 132 BC | ||

| Preceded by Phraates I |

King of Parthia 165–132 BC |

Succeeded by Phraates II |