British Empire in World War II

When the United Kingdom declared war on Nazi Germany at the outset of World War II it controlled to varying degrees numerous crown colonies, protectorates and the Indian Empire. It also maintained unique political ties to four independent dominions—Australia, Canada, South Africa, and New Zealand[1]—as part of the Commonwealth.[2] In 1939 the British Commonwealth was a global superpower, with direct or de facto political and economic control of 25% of the world's population, and 30% of its land mass.

The contribution of the British Empire and Commonwealth in terms of manpower and materiel was critical to the Allied war effort. From September 1939 to mid-1942 Britain led Allied efforts in almost every global military theatre. Commonwealth forces (United Kingdom, Colonial, Imperial and Dominion), totalling close to 15 million serving men and women, fought the German, Italian, Japanese and other Axis armies, air forces and navies across Europe, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, India, the Mediterranean and in the Atlantic, Indian, Pacific and Arctic Oceans. Commonwealth forces fought in Britain, Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Denmark and France in the effort to slow or stop the German advance across western and northern Europe. Commonwealth airforces fought the Luftwaffe to a standstill over Britain, and its armies fought and destroyed Italian forces in North and East Africa and occupied several overseas colonies of German-occupied European nations. Following successful engagements against Axis forces, Commonwealth troops invaded and occupied Libya, Italian Somaliland, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Madagascar.

The Commonwealth defeated, held back or slowed the Axis powers for three years while mobilizing their globally integrated economy, military, and industrial infrastructure to build what became, by 1942, the most extensive military apparatus of the war. These early, stand alone, efforts came at the enormous cost of 150,000 military deaths, 400,000 wounded, 100,000 prisoners, over 300,000 civilian deaths, and the loss of 70 major warships, 39 submarines, 3,500 aircraft, 1,100 tanks and 65,000 vehicles. This effort and sacrifice bought time for later allies (such as the United States) to mobilise their economies and develop the political will, and military forces required to play a role in the war effort. During this period the Commonwealth built an enormous military and industrial capacity. Britain became the nucleus of the Allied war effort in Europe, and established governments in exile in London to rally support in occupied Europe for the Allied effort. Canada delivered almost $4 Billion in direct financial aid to the United Kingdom, and Australia and New Zealand began shifting to domestic production to provide material aid to US forces in the Pacific. Following the US entry into the war, the Commonwealth and United States, coordinated their military efforts and resources globally. As the scale of the US military involvement and industrial production increased the US undertook command of many theatres, relieving Commonwealth forces for duty elsewhere, and expanding the scope and intensity of Allied military efforts.[3][4][5]

However, it also proved difficult to co-ordinate the defence of far-flung colonies and Commonwealth countries from simultaneous attacks by the Axis Powers. In part this was exacerbated by disagreements over priorities and objectives, as well as the deployment and control of joint forces. The governments of Britain and Australia, in particular, turned to the United States for support. Although the British Empire and the Commonwealth countries all emerged from the war as victors, and the conquered territories were returned to British rule, the costs of the war and the nationalist fervour that it had stoked became a catalyst for the decolonisation which took place in the following decades.

Pre-war plans for defence

From 1923, defence of British colonies and protectorates in East Asia was centred on the "Singapore strategy". This made the assumption that Britain could send a fleet to its naval base in Singapore within two or three days of a Japanese attack, while relying on France to provide assistance in Asia via its colony in Indochina and, in the event of war with Italy, to help defend British territories in the Mediterranean.[6]

During the 1930s, a triple threat emerged for the British Commonwealth in the form of right-wing, militaristic governments in Germany, Italy and Japan.[7] Germany threatened the British mainland itself, while Italy and Japan's imperial ambitions looked set to clash with British imperial presence in the Mediterranean and Far East respectively. However, there were differences of opinion within the UK and the Dominions as to which posed the most serious threat, and whether any attack would come from more than one power at the same time.

Declaration of war against Germany

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, on 3 September, after a British ultimatum to Germany to cease military operations was ignored, Britain and France declared war on Germany. Britain's declaration of war automatically committed India, the Crown colonies, and the protectorates, but the 1931 Statute of Westminster had granted autonomy to the Dominions so each decided their course separately.

Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies immediately joined the British declaration on 3 September, believing that it applied to all subjects of the Empire and Commonwealth. New Zealand's Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage followed suit within a few hours, also on 3 September, having consulted his Cabinet. South Africa took three days to make its decision (on 6 September), as the Prime Minister General J. B. M. Hertzog favoured neutrality but was defeated by the pro-war vote in the Union Parliament, led by General Jan Smuts, who then replaced Hertzog. Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King declared support for Britain on the day of the British declaration, but also stated that it was for Parliament to make the formal declaration, which it did so one week later on 10 September. The Irish Free State, which had been a dominion until 1937, remained neutral[8]

Empire and Commonwealth contribution

While the war was initially intended to be limited, resources were mobilized quickly, and the first shots were fired almost immediately. Just several hours after the declaration of war a gun at Fort Queenscliff fired across the bows of a ship as it attempted to leave Melbourne without required clearances.[9] On 10 October 1939 an aircraft of the RAAF based in England, became the first Commonwealth air-force unit to go into action when it undertook a mission to Tunisia.[10] The first Canadian convoy of 15 ships bearing war goods departed Halifax just six days after the nation declared war, with two destroyers HMCS St. Laurent and HMCS Saguenay.[11] A further 26 convoys of 527 ships sailed from Canada in the first 4 months of the war,[12] and by 1 January 1940 Canada had landed an entire division in Britain,.[13] On 13 June 1940 Canadian troops deployed to France in an attempt to secure the southern flank of the British Expeditionary Force in Belgium. As the fall of France grew imminent Britain looked to Canada to rapidly provide additional troops to strategic locations in North America, the Atlantic and Caribbean. Following the Canadian destroyer already on station from 1939, Canada provided troops from May 1940 to assist in the defence of the West Indies with several companies serving throughout the war in Bermuda, Jamaica, the Bahamas and British Guiana. Canadian troops were also sent to the defence of the colony of Newfoundland, on Canada's east coast, the closest point in North America to Germany. Fearing the loss of a land link to the British Isles, Canada was also requested to also occupy Iceland, which it did from June 1940 to the spring of 1941, following the initial British invasion.[14]

From mid-June 1940, following the rapid German invasions and occupations of Poland, Denmark, Norway, France, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, the British Commonwealth stood alone against Germany and the Axis, until the entry into the war of the Soviet Union the following year, in June 1941. During this period Australia, India, New Zealand and South Africa provided dozens of ships and several divisions for the defence of the Mediterranean, Greece, Crete, Lebanon and Egypt, where British troops were outnumbered four to one by the Italian armies in Libya and Ethiopia.[15][16] Canada delivered a further division, pilots for two air squadrons, and several warships to Britain to face what was then considered to be imminent invasion from Europe.

In December 1941, Japan launched, in quick succession, attacks on British Malaya, the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, and Hong Kong.

Substantial financial support was provided by Canada to the UK and Commonwealth dominions, in the form of over $4 billion in aid through the "Billion Dollar Gift" and the War Appropriation Act. Over the course of the war over 1.6 million Canadians serve in uniform (out of a prewar population of 11 million), in almost every theatre of the war, and by wars end the country had the third-largest navy and fourth-largest air force in the world. By the end of the war, almost a million Australians had served in the armed forces (out of a population of under 7 million), whose military units fought primarily in the Europe, North Africa, and the South West Pacific.

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (also known as the "Empire Air Training Scheme") was established by the governments of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the UK resulting in:

- joint training at flight schools in Canada, Southern Rhodesia, Australia and New Zealand;[17]

- formation of new squadrons of the Dominion air forces, known as "Article XV squadrons" for service as part of Royal Air Force operational commands, and;

- in practice, the pooling of RAF and Dominion air force personnel, for posting to both RAF and Article XV squadrons.

Crisis in the Mediterranean

In June 1940, France surrendered to invading German forces, and Italy joined the war on the Axis side, causing a reversal of the Singapore strategy. Winston Churchill, who had replaced Neville Chamberlain as British Prime Minister the previous month, ordered that the Middle East and the Mediterranean were of a higher priority than the Far East to defend.[18] Australia and New Zealand were told by telegram that they should turn to the United States for help in defending their homeland should Japan attack:[19]

Without the assistance of France we should not have sufficient forces to meet the combined German and Italian navies in European waters and the Japanese fleet in the Far East. In the circumstances envisaged, it is most improbable that we could send adequate reinforcements to the Far East. We should therefore have to rely on the United States of America to safeguard our interests there.[20]

Commonwealth forces played a major role in North and East Africa following Italy's entry to the war, participating in the invasion of Italian Libya and Somaliland, but were forced to retreat after Churchill diverted resources to Greece and Crete.[21]

Fall of Singapore

The Battle of Singapore was fought in the South-East Asian theatre of World War II when the Empire of Japan invaded the Allied stronghold of Singapore. Singapore was the major British military base in South East Asia and nicknamed the "Gibraltar of the East". The fighting in Singapore lasted from 31 January 1942 to 15 February 1942.

It resulted in the fall of Singapore to the Japanese, and the largest surrender of British-led military personnel in history.[22] About 80,000 British, Australian and Indian troops became prisoners of war, joining 50,000 taken by the Japanese in the Malayan campaign. Britain's Prime Minister Winston Churchill called the ignominious fall of Singapore to the Japanese the "worst disaster" and "largest capitulation" in British history.[23]

Victory

On 8 May 1945, the World War II Allies formally accepted the unconditional surrender of the armed forces of Nazi Germany and the end of Adolf Hitler's Third Reich. The formal surrender of the occupying German forces in the Channel Islands was not until 9 May 1945. On 30 April Hitler committed suicide during the Battle of Berlin, and so the surrender of Germany was authorized by his replacement, President of Germany Karl Dönitz. The act of military surrender was signed on 7 May in Reims, France, and ratified on 8 May in Berlin, Germany.

In the afternoon of 15 August 1945, the Surrender of Japan occurred, effectively ending World War II. On this day the initial announcement of Japan's surrender was made in Japan, and because of time zone differences it was announced in the United States, Western Europe, the Americas, the Pacific Islands, and Australia/New Zealand on 14 August 1945. The signing of the surrender document occurred on 2 September 1945.

Aftermath

By the end of the war in August 1945, British Commonwealth forces were responsible for the civil and/or military administration of a number of non-Commonwealth territories, occupied during the war, including Eritrea, Libya, Madagascar. Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Italian Somaliland, Syria, Thailand and portions of Germany, Austria and Japan. Most of these military administrations were handed over to old European colonial authorities or to new local authorities soon after the end of the hostilities. The British Empire forces administered occupation zones in Japan, Germany and Austria until 1955. World War II confirmed that Britain was no longer the great power it had once been, and that it had been surpassed by the United States on the world stage. Canada, Australia and New Zealand moved within the orbit of the United States. The image of imperial strength in Asia had been shattered by the Japanese attacks, and British prestige there was irreversibly damaged.[24] The price for India's entry to the war had been effectively a guarantee for independence, which came within two years of the end of the war, relieving Britain of its most populous and valuable colony. The deployment of 150,000 Africans overseas from British colonies, and the stationing of white troops in Africa itself led to revised perceptions of the Empire in Africa.[25]

Military histories of the British Empire, Colonies and Dominions

The contributions from individual colonies, protectorates and dominions to the war effort were extensive and global. Further information about their involvement can be found in the military histories of the individual colonies and dominions listed below.

-

United Kingdom

United Kingdom -

Aden

Aden  Ascension

Ascension Australia

Australia-

.png) Barbados

Barbados -

Basutoland

Basutoland -

Bechuanaland

Bechuanaland -

Bermuda

Bermuda -

.png) British Guiana

British Guiana -

.svg.png) British Honduras

British Honduras -

British Leeward Islands

British Leeward Islands -

British Malaya

British Malaya -

British Mauritius

British Mauritius .svg.png) British Solomon Islands

British Solomon Islands.png) British Somaliland

British Somaliland-

.svg.png) British Windward Islands

British Windward Islands -

Protectorate of Brunei

Protectorate of Brunei -

.svg.png) Burma

Burma -

Canada

Canada -

Cayman Islands

Cayman Islands -

Ceylon

Ceylon -

.svg.png) Cyprus

Cyprus -

Dominica

Dominica -

.svg.png) Egypt

Egypt -

Falkland Islands

Falkland Islands -

Fiji

Fiji -

.svg.png) Gambia

Gambia -

Gibraltar

Gibraltar -

Gilbert and Ellice Islands

Gilbert and Ellice Islands -

Gold Coast

Gold Coast -

.svg.png) Grenada

Grenada -

.svg.png) Guernsey

Guernsey -

.svg.png) Hong Kong

Hong Kong -

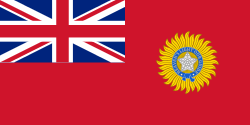

India

India -

.svg.png) Jamaica

Jamaica -

Jersey

Jersey -

Kenya

Kenya -

.svg.png) Malta

Malta -

Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine -

Mauritius

Mauritius  Nauru

Nauru-

Newfoundland

Newfoundland  New Guinea

New Guinea.svg.png) New Hebrides

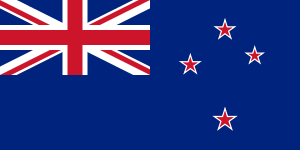

New Hebrides New Zealand

New Zealand-

Nigeria

Nigeria  Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island-

North Borneo

North Borneo -

.svg.png) Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia -

.svg.png) Nyasaland

Nyasaland  Papua

Papua St Helena

St Helena.svg.png) Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia.svg.png) Saint Vincent

Saint Vincent-

.svg.png) Sarawak

Sarawak -

Seychelles

Seychelles -

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone -

.svg.png) Singapore

Singapore -

.svg.png) South Africa

South Africa -

.svg.png) South-West Africa

South-West Africa -

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia -

.svg.png) Straits Settlements

Straits Settlements -

Sudan

Sudan .svg.png) Tanganyika

Tanganyika Tonga Protectorate

Tonga Protectorate Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago Turks and Caicos

Turks and Caicos Uganda Protectorate

Uganda Protectorate Western Samoa

Western Samoa Zanzibar

Zanzibar- Nepal in the Second World War

- British Military Administration (Borneo)

- British Military Administration (Eritrea)

- British Military Administration of Italian Somaliland

- British Military Administration (Libya)

- British Military Administration (Malaya)

- British Military Administration (Somalia)

See also

Homefront

- Australian home front during the Second World War

- Christmas Island Mutiny and Battle

- Gibraltar evacuation in the Second World War

- British home front during the Second World War

- Japanese occupation of the Andaman Islands

- Japanese occupation of British Borneo

- Japanese occupation of Burma

- Japanese occupation of Hong Kong

- Japanese occupation of Malaya

- Japanese occupation of Nauru

- Japanese occupation of Singapore

- German occupation of the Channel Islands

Major military formations and units

- List of British Empire corps of the Second World War

- List of British Empire divisions in the Second World War

- List of British Empire brigades of the Second World War

- East Africa Command

- Far East Command

- India Command

- Malaya Command

- Middle East Command

- Persia and Iraq Command

- West Africa Command

- Pacific Fleet

- Eastern Fleet

- Home Fleet

- Mediterranean Fleet

- Reserve Fleet

- Bomber Command

- Ferry Command

- Fighter Command

- RAF Squadrons

- British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

- British Commonwealth Occupation Force

References

- ↑ Ireland was also technically a dominion but operated largely as a republic and remained neutral during the war)

- ↑ The term was popularised during World War I and became official after the Balfour Declaration in 1926. W. David McIntyre, 1999, "The Commonwealth"; in Robin Winks (ed.), The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume V: Historiography, Oxford University Press, p. 558.

- ↑ History of the Second World War (104 volumes), Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1949 to 1993

- ↑ Stacey, C P. (1970)

- ↑ Edgerton, David (2011)

- ↑ Louis, p. 315

- ↑ Brown, p. 284

- ↑ Brown, pp. 307–9

- ↑ McKernan (1983). p. 4.

- ↑ Stephens (2006). pp. 76–79.

- ↑ Byers, A.R., ed. (1986). The Canadians at War 1939–45. Westmount, QC: The Readers' Digest Association. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-88850-145-5.

- ↑ Hague, 2000

- ↑ Byers, p.26

- ↑ Stacey 1970

- ↑ McIntyre pp. 336–7

- ↑ Grey (2008). pp. 156–164.

- ↑ Brown, p. 310

- ↑ Louis, p. 335

- ↑ McIntyre p. 339

- ↑ Brown, p. 317

- ↑ McIntyre p. 337

- ↑ Smith, Colin (2006). Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II. Penguin Group. ISBN 0-14-101036-3.

- ↑ Churchill, Winston (1986). The Hinge of Fate, Volume 4. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, p. 81. ISBN 0395410584

- ↑ McIntyre, p. 341

- ↑ McIntyre, p. 342

Bibliography

- Brown, Judith (1998). The Twentieth Century, The Oxford History of the British Empire Volume IV. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924679-3.

- Bryce, Robert Broughton (2005). Canada and the cost of World War II. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2938-0.

- Butler, J.R.M. et al. Grand Strategy (6 vol 1956–60), official overview of the British war effort; Volume 1: Rearmament Policy; Volume 2: September 1939 – June 1941; Volume 3, Part 1: June 1941 – August 1942; Volume 3, Part 2: June 1941 – August 1942; Volume 4: September 1942 – August 1943; Volume 5: August 1943 – September 1944; Volume 6: October 1944 – August 1945

- Chartrand, René; Ronald Volstad (2001). Canadian Forces in World War II. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-302-0

- Copp, J. T; Richard Nielsen (1995). No price too high: Canadians and the Second World War. McGraw-Hill Ryerson. ISBN 0-07-552713-8.

- Edgerton, David. Britain's War Machine: Weapons, Resources, and Experts in the Second World War (Oxford University Press; 2011) 445 pages

- Hague, Arnold: The allied convoy system 1939–1945 : its organization, defence and operation. St.Catharines, Ontario : Vanwell, 2000.

- Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1852854171.

- Louis, Wm. Roger (2006). Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez and Decolonization. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-347-0.

- McIntyre, W. Donald (1977). The Commonwealth of Nations. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0792-3.

- Morton, Desmond (1999). A military history of Canada (4th ed.). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-6514-0.

- Mulvey, Paul. The British Empire in World War II. Academic.edu.

- Roberts, Andrew. Masters and Commanders – How Roosevelt, Churchill, Marshall and Alanbrooke Won the War in the West (2008)

- Stacey, C P. (1970) Arms, Men and Governments: The War Policies of Canada, 1939–1945 Queen's Printer, Ottawa (Downloadable PDF) ISBN D2-5569

- Stewart, Andrew (2008). Empire Lost: Britain, the Dominions and the Second World War. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1847252449.

Further reading

- Butler, J.R.M. et al. Grand Strategy (6 vol 1956–60), official overview of the British war effort; Volume 1: Rearmament Policy; Volume 2: September 1939 – June 1941; Volume 3, Part 1: June 1941 – August 1942; Volume 3, Part 2: June 1941 – August 1942; Volume 4: September 1942 – August 1943; Volume 5: August 1943 – September 1944; Volume 6: October 1944 – August 1945

- Churchill, Winston. The Second World War (6 vol 1947–51), classic personal history with many documents

- Edgerton, David. Britain's War Machine: Weapons, Resources, and Experts in the Second World War (Oxford University Press; 2011) 445 pages

- Harrison, Mark Medicine and Victory: British Military Medicine in the Second World War (2004). ISBN 0-19-926859-2

- Hastings, Max. Winston's War: Churchill, 1940–1945 (2010)

- Roberts, Andrew. Masters and Commanders – How Roosevelt, Churchill, Marshall and Alanbrooke Won the War in the West (2008)

Army

- Allport, Alan. Browned Off and Bloody-Minded: The British Soldier Goes to War, 1939–1945 (Yale UP, 2015)

- Atkinson, Rick. The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943–1944 (2008) excerpt and text search

- Buckley, John. British Armour in the Normandy Campaign 1944 (2004)

- D'Este, Carlo. Decision in Normandy: The Unwritten Story of Montgomery and the Allied Campaign (1983). ISBN 0-00-217056-6.

- Ellis, L.F. The War in France and Flanders, 1939–1940 (HMSO, 1953) online

- Ellis, L.F. Victory in the West, Volume 1: Battle of Normandy (HMSO, 1962)

- Ellis, L.F. Victory in the West, Volume 2: Defeat of Germany (HMSO, 1968)

- Fraser, David. And We Shall Shock Them: The British Army in World War II (1988). ISBN 978-0-340-42637-1

- Graham, Dominick. Tug of War: The Battle for Italy 1943–1945 (2004)

- Hamilton, Nigel. Monty: The Making of a General: 1887–1942 (1981); Master of the Battlefield: Monty's War Years 1942–1944 (1984); Monty: The Field-Marshal 1944–1976 (1986).

- Lamb, Richard. War In Italy, 1943–1945: A Brutal Story (1996)

- Thompson, Julian. The Imperial War Museum Book of the War in Burma 1942–1945 (2004)

- Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh. Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man (2008)

Royal Navy

- Barnett, Corelli. Engage the Enemy More Closely: The Royal Navy in the Second World War (1991)

- Marder, Arthur. Old Friends, New Enemies: The Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy, vol. 2: The Pacific War, 1942–1945 with Mark Jacobsen and John Horsfield (1990)

- Roskill, S. W. The White Ensign: British Navy at War, 1939–1945 (1960). summary

- Roskill, S. W. War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 1: The Defensive London: HMSO, 1954; War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 2: The Period of Balance, 1956; War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 3: The Offensive, Part 1, 1960; War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 3: The Offensive, Part 2, 1961. online vol 1; online vol 2

Air war

- Bungay, Stephen. The Most Dangerous Enemy: The Definitive History of the Battle of Britain (2nd ed. 2010)

- Collier, Basil. Defence of the United Kingdom (HMSO, 1957) online

- Fisher, David E, A Summer Bright and Terrible: Winston Churchill, Lord Dowding, Radar, and the Impossible Triumph of the Battle of Britain (2005) excerpt online

- Hastings, Max. Bomber Command (1979)

- Hansen, Randall. Fire and Fury: The Allied Bombing of Germany, 1942–1945 (2009)

- Hough, Richard and Denis Richards. The Battle of Britain (1989) 480 pp

- Messenger, Charles, "Bomber" Harris and the Strategic Bombing Offensive, 1939–1945 (1984), defends Harris

- Overy, Richard. The Battle of Britain: The Myth and the Reality (2001) 192 pages excerpt and text search

- Richards, Dennis, et al. Royal Air Force, 1939–1945: The Fight at Odds – Vol. 1 (HMSO 1953), official history vol 1 online edition vol 2 online edition; vol 3 online edition

- Shores, Christopher F. Air War for Burma: The Allied Air Forces Fight Back in South-East Asia 1942–1945 (2005)

- Terraine, John. A Time for Courage: The Royal Air Force in the European War, 1939–1945 (1985)

- Verrier, Anthony. The Bomber Offensive (1969), British

- Webster, Charles and Noble Frankland, The Strategic Air Offensive Against Germany, 1939–1945 (HMSO, 1961), 4 vol. Important official British history

- Wood, Derek, and Derek D. Dempster. The Narrow Margin: The Battle of Britain and the Rise of Air Power 1930–40 (1975) online edition