Mile End

| Mile End | |

The Green Bridge carries Mile End Park over the Mile End Road |

|

Mile End |

|

| OS grid reference | TQ365825 |

|---|---|

| – Charing Cross | 3.6 mi (5.8 km) WSW |

| London borough | Tower Hamlets |

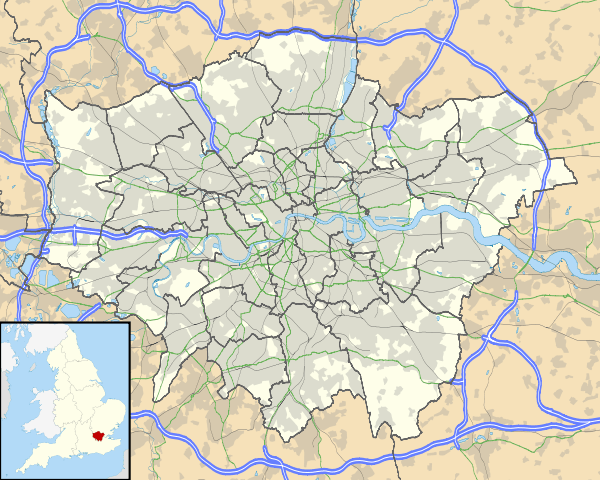

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | London |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | E1, E3 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| EU Parliament | London |

| UK Parliament | Bethnal Green and Bow |

| Poplar and Limehouse | |

| London Assembly | City and East |

Coordinates: 51°31′29″N 0°01′53″W / 51.5248°N 0.0314°W

Mile End is a district in East London, England, 3.6 miles (5.8 km) east-northeast of Charing Cross. On the London to Colchester road, it was one of the earliest suburbs of the City of London and became part of the metropolitan area of London in 1855. In 2011, Mile End had a population of 28,544.[1]

History

Toponymy

Mile End is recorded in 1288 as La Mile ende.[2] It is formed from the Middle English 'mile' and 'ende' and means 'the hamlet a mile away'. The mile distance was in relation to Aldgate in the City of London, reached by the London to Colchester road.[2] In around 1691 Mile End became known as Mile End Old Town because a new unconnected settlement to the west and adjacent to Spitalfields had taken the name Mile End New Town.[2] This data combines the ethnicity data for Mile End's two wards (Mile End And Globe Town and Mile End East). [3][4]

| Mile End Compared 2011 | White British | Asian | Black |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mile End Population 28,544 | 29.3% | 44.8% | 8.5% |

| London Borough of Tower Hamlets | 31.2% | 41.2% | 7.3% |

Beginnings

Whilst there are many references to settlements in the area, excavations have suggested there were very few buildings before 1300.

Mile End Road is an ancient route from London to the East, and was moved to its present-day alignment after the foundation of Bow Bridge in 1110. In the medieval period it was known as ‘Aldgatestrete’, as it led to the eastern entrance to the City of London at Aldgate. The area running alongside Mile End Road was known as Mile End Green, and became known as a place of assembly for Londoners, reflected in the name of Assembly Passage. For most of the medieval period, this road was surrounded by open fields on either side, but speculative developments existed by the end of the 16th century and continued throughout the 18th century.

The Stepney Green Conservation Area was designated in January 1973, covering the area previously known as Mile End Old Town. It is a large Conservation Area with an irregular shape that encloses buildings around Mile End Road, Assembly Passage, Louisa Street and Stepney Green itself. It is an area of exceptional architectural and historic interest, with a character and appearance worthy of protection and enhancement. It is situated just north of the medieval village of Stepney, which was clustered around St. Dunstan’s Church.[5]

Peasants' Revolt

In 1381, an uprising against the tax collectors of Brentwood quickly spread first to the surrounding villages, then throughout the South-East of England, but it was the rebels of Essex, led by a priest named Jack Straw, and the men of Kent, led by Wat Tyler, who marched on London. On 12 June, the Essex rebels, comprising 100,000 men, camped at Mile End and on the following day the men of Kent arrived at Blackheath. On 14 June, the young king Richard II rode to Mile End where he met the rebels and signed their charter. The king subsequently had the leaders and many rebels executed.[6]

Birth of London's Yiddish theatre

In 1883, Jacob P. Adler arrived in London with a troupe of refugee professional actors. He enlisted the help of local amateurs, and the Russian Jewish Operatic Company made their debut at the Beaumont Hall, close to Stepney Green tube station. Within two years they were able to establish their own theatre in Brick Lane.[7]

People's Palace

Novelist and social commentator Walter Besant proposed a Palace of Delight[8] with concert halls, reading rooms, picture galleries, an art school and various classes, social rooms and frequent fêtes and dances. This coincided with a project by the philanthropist businessman Edmund Hay Currie to use the money from the winding up of the Beaumont Trust,[9] together with subscriptions, to build a People's Palace in the East End. Five acres of land were secured on the Mile End Road, and the Queen's Hall was opened by Queen Victoria on 14 May 1887. The complex was completed with a library, swimming pool, gymnasium and winter garden by 1892, providing an eclectic mix of populist entertainment and education. A peak of 8,000 tickets were sold for classes in 1892, and by 1900, a Bachelor of Science degree awarded by the University of London was introduced.[10] In 1931, the building was destroyed by fire, but the Draper's Company, major donors to the original scheme, invested more to rebuild the technical college and create Queen Mary College in December 1934.[11] A new People's Palace was constructed, in 1937, by the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney, in St Helen's Terrace. This finally closed in 1954.[12]

Second World War

Besides suffering heavily in earlier blitzes, Mile End was hit by the first V-1 flying bomb to strike London. On 13 June 1944, this 'doodlebug' impacted next to the railway bridge on Grove Road, an event now commemorated by a plaque. Eight civilians were killed, 30 injured and 200 made homeless by the blast.[13] The area remained derelict for many years, until cleared to extend Mile End park. Before demolition in 1993, local artist Rachel Whiteread made a cast of the inside of 193 Grove Road. Despite attracting controversy, the exhibit won her the Turner Prize for 1993.[14]

In May 2007 during building work, a live World War II bomb weighing 200 kg was found north of Mile End station near Grove and Roman Roads. Approximately 100 local residents were evacuated and stayed with friends and family or the Mile End Leisure Centre until the bomb could be deactivated and removed.

Governance

Mile End formed a hamlet within the large ancient parish of Stepney, in the Tower division of the Ossulstone hundred of Middlesex. It was grouped into the Stepney poor law union in 1836, becoming a single parish for poor law purposes in 1857. It formed part of the Metropolitan Police District from 1830. Upon the creation of the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1855 the vestry of Mile End Old Town became an electing authority. The vestry hall was located on Bancroft Road. The parish became part of the County of London in 1889 and in 1900 it became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney. In 1965 Stepney was incorporated into the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. There was a Mile End Parliament constituency from 1885 to 1950 which was notable for being one of two constituencies in the UK to elect a Communist Party MP.

Politics

Under the Metropolis Management Act 1855 any parish that exceeded 2,000 ratepayers was to be divided into wards; as such the incorporated vestry of the Hamlet of Mile End Old Town within the parish of St Dunstan Stepney was divided into five wards (electing vestrymen): No. 1 or North Ward (15), No. 2 or East Ward (12), No. 3 or West Ward (18), No. 4 or Centre Ward (21) and No. 5 or South Ward (18). [15][16][17]

In 1894 as its population had increased the incorporated vestry was re-divided into eight wards (electing vestrymen): No. 1 (9), No. 2 (9), No. 3 (12), No. 4 (12), No. 5 (12), No. 6 (9), No. 7 (12) and No. 8 (15).[18][19]

Geography

Mile End is in a part of London known as the East End and home to the main campus of Queen Mary, University of London. Parts of Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry are also based on this campus. The main student halls of residence are also now located on this campus.

The area also boasts an unusual landmark, the "Green Bridge". This structure (designed by CZWG Architects, and opened in 2000) allows Mile End Park to cross over the Mile End Road and makes an interesting contrast with the more usual approach of building bridges for cars. It contains garden and water features and some shops and restaurant space built in below.

The Ragged School Museum, opened in 1990 in three canal side former warehouses in Copperfield Road, facing the western edge of the park, south of Mile End Road. The buildings previously housed Dr Barnado's Cooperfield Road Ragged School.

Mile End as a parliamentary constituency had a reputation as a Labour Party stronghold, but also sent Communist Member of Parliament (MP) Phil Piratin to the House of Commons between 1945 and 1950. At that time, it had a large Jewish population. The area now is covered by the Bethnal Green and Bow and Poplar and Limehouse constituencies.

Sport and leisure

Mile End has a Non-League football club Sporting Bengal United F.C. who play at Mile End Stadium.

Media references

The neighbourhood was immortalised (humorously but unfavourably) in the pop band Pulp's song, "Mile End," which was featured on the Trainspotting soundtrack. The song describes a group of squatters taking up residence in an abandoned 15th-floor apartment in a run-down apartment tower.

A man pushed in front of a train at Mile End underground station recently attracted media attention and has resulted in an acclaimed play, called "Mile End," devised and performed by Analogue Theatre.

In 2009, the music video for "Confusion Girl" by electropop musician Frankmusik was filmed in Mile End Park and Clinton Road, Mile End.[20]

In 2011, the music video for "Heart Skips a Beat" by Olly Murs and Rizzle Kicks was filmed in Mile End's skate park.

The artistic director of the 2012 Summer Olympics opening ceremony, Danny Boyle, lives in Mile End. Boyle is also the director of Trainspotting.

Transport

|

Globe Town | South Hackney (Victoria Park) |

Bow |  |

| Whitechapel | |

Bow | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Stepney | Stepney | Poplar |

The nearest London Underground station is Mile End on the District, Hammersmith & City and Central lines.

There are major bus interchanges at Mile End Gate – for buses north towards Hackney; and near Mile End tube station – for buses north towards Hackney and south towards Canary Wharf.

See also

References

- ↑ "Mile End – Hidden London". hidden-london.com.

- 1 2 3 Mills, D. (2000). Oxford Dictionary of London Place Names. Oxford.

- ↑ Good Stuff IT Services. "Mile End and Globe Town". UK Census Data.

- ↑ Good Stuff IT Services. "Mile End East". UK Census Data.

- ↑ http://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/idoc.ashx?docid=c559f8cb-acd0-4ef7-8d69-d201d1ae0d8a&version=-1

- ↑ R. B. Dobson, editor, (2002), The Peasants' Revolt of 1381 (History in Depth) ISBN 0-333-25505-4; a collection of source materials

- Alastair Dunn (2002), The Great Rising of 1381: The Peasant's Revolt and England's Failed Revolution, ISBN 0-7524-2323-1

- ↑ The Jewish Museum accessed on 31 March 2007

- ↑ In Walter Besant All Sorts and Conditions of Men (1882)

- ↑ In 1841, John Barber Beaumont died and left property in Beaumont Square, Stepney to provide for the education and entertainment of people from the neighbourhood. The charity – and its property – was becoming moribund by the 1870s, and in 1878 it was wound up by the Charity Commissioners, providing its new chair, Sir Edmund Hay Currie, with £120,000 to invest in a similar project. He raised a further £50,000 and secured continued funding from the Draper's Company for ten years (The Whitechapel Society, below)

- ↑ G. P. Moss and M. V. Saville From Palace to College – An illustrated account of Queen Mary College (University of London) (1985) pages 39–48 ISBN 0-902238-06-X

- ↑ The People's Palace The Whitechapel Society accessed 5 July 2007 Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Origins and History Queen Mary, University of London Alumni Booklet accessed 5 July 2007

- ↑ Second World War memories (BBC) accessed 27 March 2007

- ↑ Best and worst of art bites the dust Roberts, Alison The Times, London, 12 January 1994 accessed 5 October

- ↑ The London Gazette Issue: 21802. 20 October 1855. pp. 3898–3899. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "H.M.S.O. Boundary Commission Report 1885 Mile End Old Town Map". Vision of Britain. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "H.M.S.O. Boundary Commission Report 1885 Tower Hamlets Map". Vision of Britain. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette Issue: 26542. 14 August 1894. pp. 4715–4716. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette Issue: 26563. 23 October 1894. p. 5940. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "Frankmusik – Confusion Girl". capitalfm.com.

Bibliography

- William J. Fishman, East End 1888: Life in a London Borough Among the Laboring Poor (1989)

- William J. Fishman, Streets of East London (1992) (with photographs by Nicholas Breach)

- William J. Fishman, East End Jewish Radicals 1875–1914 (2004)

- Nigel Glendinning, Joan Griffiths, Jim Hardiman, Christopher Lloyd and Victoria Poland Changing Places: a short history of the Mile End Old Town RA area (Mile End Old Town Residents’ Association, 2001)

- Derek Morris Mile End Old Town 1740–1780: A social history of an early modern London Suburb (East London History Society, 2007) ISBN 978-0-9506258-6-7

- Alan Palmer The East End (John Murray, London 1989)

- Watson, Isobel (1995). "From West Heath to Stepney Green: Building development in Mile End Old Town, 1660–1820". London Topographical Record. XXVII. London Topographical Society. pp. 231–256.

.jpg)