Middle East respiratory syndrome

| Middle East respiratory syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Middle East respiratory syndrome virus (MERS-CoV) 3-D image | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | B34.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 78.89, 480.9 |

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), also known as camel flu,[1] is a viral respiratory infection caused by the MERS-coronavirus (MERS-CoV).[2] Symptoms may range from mild to severe.[3] They include fever, cough, diarrhea, and shortness of breath.[2] Disease is typically more severe in those with other health problems.[3]

MERS-CoV is a betacoronavirus derived from bats.[2] Camels have been shown to have antibodies to MERS-CoV but the exact source of infection in camels has not been identified. Camels are believed to be involved in its spread to humans but it is unclear how.[3] Spread between humans typically requires close contact with an infected person.[2] Its spread is uncommon outside of hospitals.[3] Thus, its risk to the global population is currently deemed to be fairly low.[3]

As of 2015 there is no specific vaccine or treatment for the disease.[2][3] However, a number of antiviral medications are currently being studied.[3] The World Health Organization recommends that those who come in contact with camels wash their hands frequently and do not touch sick camels.[2] They also recommend that camel products be appropriately cooked.[2] Among those who are infected treatments that help with the symptoms may be given.[2]

Just over 1000 cases of the disease have been reported as of May 2015.[3] About 40% of those who become infected die from the disease.[3] The first identified case occurred in 2012 in Saudi Arabia and most cases have occurred in the Arabian Peninsula.[2][3] A strain of MERS-CoV known as HCoV-EMC/2012 found in the first infected person in London in 2012 was found to have a 100% match to Egyptian tomb bats. A large outbreak occurred in the Republic of Korea in 2015.

Signs and symptoms

.png)

Early reports[4] compared the virus to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and it has been referred to as Saudi Arabia's SARS-like virus.[5] The first person, in June 2012, had a "seven-day history of fever, cough, expectoration, and shortness of breath."[4] One review of 47 laboratory confirmed cases in Saudi Arabia gave the most common presenting symptoms as fever in 98%, cough in 83%, shortness of breath in 72% and myalgia in 32% of people. There were also frequent gastrointestinal symptoms with diarrhea in 26%, vomiting in 21%, abdominal pain in 17% of people. 72% of people required mechanical ventilation. There were also 3.3 males for every female.[6] One study of a hospital-based outbreak of MERS had an estimated incubation period of 5.5 days (95% confidence interval 1.9 to 14.7 days).[7] MERS can range from asymptomatic disease to severe pneumonia leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[6] Kidney failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and pericarditis have also been reported.[8]

Cause

Virology

Middle East respiratory syndrome is caused by the newly identified MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV), a species with single-stranded RNA belonging to the genus betacoronavirus which is distinct from SARS coronavirus and the common-cold coronavirus.[9] Its genomes are phylogenetically classified into two clades, Clades A and B. Early cases of MERS were of Clade A clusters (EMC/2012 and Jordan-N3/2012) while new cases are genetically different in general (Clade B).[10] The virus grows readily on Vero cells and LLC-MK2 cells.[11]

Transmission

Camels

A study performed between 2010 and 2013, in which the incidence of MERS was evaluated in 310 dromedary camels, revealed high titers of neutralizing antibodies to MERS-CoV in the blood serum of these animals.[12] A further study sequenced MERS-CoV from nasal swabs of dromedary camels in Saudi Arabia and found they had sequences identical to previously sequenced human isolates. Some individual camels were also found to have more than one genomic variant in their nasopharynx.[13] There is also a report of a Saudi Arabian man who became ill seven days after applying topical medicine to the noses of several sick camels and later he and one of the camels were found to have identical strains of MERS-CoV.[14][15] It is still unclear how the virus is transmitted from camels to humans. The World Health Organization advises avoiding contact with camels and to eat only fully cooked camel meat, pasteurized camel milk, and to avoid drinking camel urine. Camel urine is considered a medicine for various illnesses in the Middle East.[16] The Saudi Ministry of Agriculture has advised people to avoid contact with camels or wear breathing masks when around them.[17] In response "some people have refused to listen to the government's advice"[18] and kiss their camels in defiance of their government's advice.

Between people

There has been evidence of limited, but not sustained spread of MERS-CoV from person to person, both in households as well as in health care settings like hospitals.[7][19] Most transmission has occurred "in the circumstances of close contact with severely ill persons in healthcare or household settings" and there is no evidence of transmission from asymptomatic cases.[20] Cluster sizes have ranged from 1 to 26 people, with an average of 2.7.[21]

Diagnosis

According to World Health Organization, the interim case definition is that a confirmed case is identified in a person with a positive lab test by "molecular diagnostics including either a positive PCR on at least two specific genomic targets or a single positive target with sequencing on a second."[22]

World Health Organization

According to the WHO, a probable case is[22]

- a person with a fever, respiratory infection, and evidence of pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome

and

testing for MERS-CoV is unavailable or negative on a single inadequate specimen

and

the person has a direct link with a confirmed case. - A person with a acute febrile respiratory illness with clinical, radiological, or histopathological evidence of pulmonary parenchymal disease (e.g. pneumonia or acute respiratory distress Syndrome)

and

an inconclusive MERS-CoV laboratory test (that is, a positive screening test without confirmation)

and

a resident of or traveler to Middle Eastern countries where MERS-CoV virus is believed to be circulating in the 14 days before onset of illness. - A person with an acute febrile respiratory illness of any severity

and

an inconclusive MERS-CoV laboratory test (that is, a positive screening test without confirmation)

and

the person has a direct epidemiologic-link with a confirmed MERS-CoV case.

Centers for Disease Control

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend investigating any person with:[23][24]

- Fever and pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome (based on clinical or radiological evidence)

and either:- a history of travel from countries in or near the Arabian Peninsula within 14 days before symptom onset, or

- close contact with a symptomatic traveler who developed fever and acute respiratory illness (not necessarily pneumonia) within 14 days after traveling from countries in or near the Arabian Peninsula or

- a member of a cluster of people with severe acute respiratory illness (e.g. fever and pneumonia requiring hospitalization) of unknown etiology in which MERS-CoV is being evaluated, in consultation with state and local health departments.

- Fever and symptoms of respiratory illness (not necessarily pneumonia; e.g. cough, shortness of breath) and being in a healthcare facility (as a patient, worker, or visitor) within 14 days before symptom onset in a country or territory in or near the Arabian Peninsula in which recent healthcare-associated cases of MERS have been identified.

- Fever or symptoms of respiratory illness (not necessarily pneumonia; e.g. cough, shortness of breath) and close contact with a confirmed MERS case while the case was ill.

Radiology

Chest X-ray findings tend to show bilateral patchy infiltrates consistent with viral pneumonitis and ARDS. Lower lobes tend to be more involved. CT scans show interstitial infiltrates.[19]

Laboratory testing

MERS cases have been reported to have low white blood cell count, and in particular low lymphocytes.[19]

For PCR testing, the WHO recommends obtaining samples from the lower respiratory tract via bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), sputum sample or tracheal aspirate as these have the highest viral loads.[25] There have also been studies utilizing upper respiratory sampling via nasopharyngeal swab.[6]

Several highly sensitive, confirmatory real-time RT-PCR assays exist for rapid identification of MERS-CoV from patient-derived samples. These assays attempt to amplify upE (targets elements upstream of the E gene),[26] open reading frame 1B (targets the ORF1b gene)[26] and open reading frame 1A (targets the ORF1a gene).[27] The WHO recommends the upE target for screening assays as it is highly sensitive.[25] In addition, hemi-nested sequencing amplicons targeting RdRp (present in all coronaviruses) and nucleocapsid (N) gene[28] (specific to MERS-CoV) fragments can be generated for confirmation via sequencing. Reports of potential polymorphisms in the N gene between isolates highlight the necessity for sequence-based characterization.

The WHO recommended testing algorithm is to start with an upE RT-PCR and if positive confirm with ORF 1A assay or RdRp or N gene sequence assay for confirmation. If both an upE and secondary assay are positive it is considered a confirmed case.[25]

Protocols for biologically safe immunofluorescence assays (IFA) have also been developed; however, antibodies against betacoronaviruses are known to cross-react within the genus. This effectively limits their use to confirmatory applications.[27] A more specific protein-microarray based assay has also been developed that did not show any cross-reactivity against population samples and serum known to be positive for other betacoronaviruses.[29] Due to the limited validation done so far with serological assays, WHO guidance is that "cases where the testing laboratory has reported positive serological test results in the absence of PCR testing or sequencing, are considered probable cases of MERS-CoV infection, if they meet the other conditions of that case definition."[25]

Prevention

While the mechanism of spread of MERS-CoV is currently not known, based on experience with prior coronaviruses, such as SARS, the WHO currently recommends that all individuals coming into contact with MERS suspects should (in addition to standard precautions):

- Wear a medical mask

- Wear eye protection (i.e. goggles or a face shield)

- Wear a clean, non sterile, long sleeved gown; and gloves (some procedures may require sterile gloves)

- Perform hand hygiene before and after contact with the person and his or her surroundings and immediately after removal of personal protective equipment (PPE)[30]

For procedures which carry a risk of aerosolization, such as intubation, the WHO recommends that care providers also:

- Wear a particulate respirator and, when putting on a disposable particulate respirator, always check the seal

- Wear eye protection (i.e. goggles or a face shield)

- Wear a clean, non-sterile, long-sleeved gown and gloves (some of these procedures require sterile gloves)

- Wear an impermeable apron for some procedures with expected high fluid volumes that might penetrate the gown

- Perform procedures in an adequately ventilated room; i.e. minimum of 6 to 12 air changes per hour in facilities with a mechanically ventilated room and at least 60 liters/second/patient in facilities with natural ventilation

- Limit the number of persons present in the room to the absolute minimum required for the person’s care and support

- Perform hand hygiene before and after contact with the person and his or her surroundings and after PPE removal.[30]

The duration of infectivity is also unknown so it is unclear how long people must be isolated, but current recommendations are for 24 hours after resolution of symptoms. In the SARS outbreak the virus was not cultured from people after the resolution of their symptoms.[31]

It is believed that the existing SARS research may provide a useful template for developing vaccines and therapeutics against a MERS-CoV infection.[32][33] Vaccine candidates are currently awaiting clinical trials.[34][35]

Treatment

Neither the combination of antivirals and interferons (ribavirin + interferon alfa-2a or interferon alfa-2b) nor corticosteroids improved outcomes.[36]

When rhesus macaques were given interferon-α2b and ribavirin and exposed to MERS, they developed less pneumonia than control animals.[37] Five critically ill people with MERS in Saudi Arabia with ARDS and on ventilators were given interferon-α2b and ribavirin but all ended up dying of the disease. The treatment was started late in their disease (a mean of 19 days after hospital admission) and they had already failed trials of steroids so it remains to be seen whether it may have benefit earlier in the course of disease.[38][39] Another proposed therapy is inhibition of viral protease[40] or kinase enzymes.[41] Researchers are investigating a number of ways to combat the outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, including using interferon, chloroquine, chlorpromazine, loperamide, and lopinavir,[42] as well as other agents such as mycophenolic acid[43][44] and camostat.[45][46]

Epidemiology

| Cases | Deaths | Fatality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO total[47] | 1227 | 449 | 37% |

| ECDC total[48] | 1082 | 439 | 41% |

| Reported confirmed cases per country | |||

| Saudi Arabia[49] | 1029 | 452 | 44% |

| South Korea[50] | 184 | 29 | 16% |

| United Arab Emirates[48] | 74 | 10 | 14% |

| Jordan[48] | 19 | 6 | 32% |

| Qatar[48] | 10 | 4 | 40% |

| Oman[48] | 5 | 3 | 60% |

| Iran[48] | 5 | 2 | 40% |

| United Kingdom[48] | 4 | 3 | 75% |

| Germany[48] | 3 | 1 | 33% |

| Kuwait[48] | 3 | 1 | 33% |

| Algeria[48] | 2 | 1 | 50% |

| Tunisia[48] | 3 | 1 | 33% |

| France[48] | 2 | 1 | 50% |

| Spain[51][52] | 2 | 0 | 0% |

| Netherlands[48][53] | 2 | 0 | 0% |

| Philippines[48] | 2 | 0 | 0% |

| United States[48] | 2 | 0 | 0% |

| Greece[48] | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Malaysia[48] | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Turkey[48][54] | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Yemen[48] | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Austria[48] | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Egypt[48][55] | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Italy[48] | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Lebanon[48][56] | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Thailand[57] | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Serbia | 4 | 1 | 25% |

| Reported total | 1342 | 513 | 38% |

Saudi Arabia

MERS was also implicated in an outbreak in April 2014 in Saudi Arabia, where MERS has infected 688 people and 282 MERS-related deaths have been reported since 2012.[58] In response to newly reported cases and deaths, and the resignation of four doctors at Jeddah’s King Fahd Hospital who refused to treat MERS patients for fear of infection, the government has removed the Minister of Health and set up three MERS treatment centers.[59][60] 18 more cases were reported in early May.[61] In June 2014, Saudi Arabia announced 113 previously unreported cases of MERS, revising the death toll to 282.

A hospital-related outbreak in Riyadh in the summer of 2015 increased fears of an epidemic occurring during the annual Hajj pilgrimage that begins in late September. After a period of few cases, cases began increasing in the middle of the summer.[62] The CDC placed the travel health alert to level 2, which calls for taking enhanced precautions.[63]

United States

On 2 May 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first diagnosis of MERS in the United States in Indiana. The man diagnosed was a health care worker who had been in Saudi Arabia a week earlier, and was reported to be in good condition.[64][65] A second patient who also traveled from Saudi Arabia was reported in Orlando, Florida on 12 May 2014.[66][67] On 14 May 2014, officials in the Netherlands reported the first case has appeared.[68] On Saturday, 17 May 2014, a man from Illinois who was a business associate of the first U.S. case (he had met and shook hands with the Indiana health care worker) tested positive for the MERS coronavirus, but has not, as of yet, displayed symptoms (others are probably also, at least temporarily if not permanently, non-symptomatic carriers). The CDC's Dr. David Swerdlow, who is leading the agency's response, said the man, who feels well and has not yet sought and does not yet need medical care, has not been deemed an official case yet and prevention guidelines have not changed. Laboratory tests showed evidence of past infection in his blood.[69]

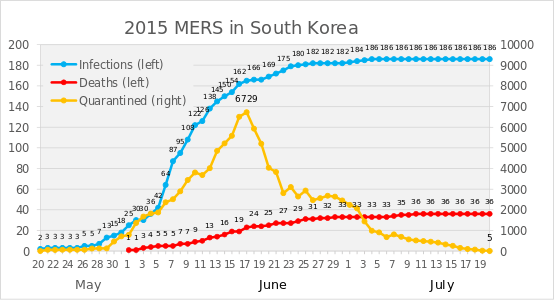

South Korea

In May 2015, the first case in South Korea was confirmed in a man who had visited Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.[70] Another man from South Korea, who was travelling to China, was diagnosed as the first case in China. So far, no Chinese citizen has been found infected.[71]

As of 27 June 2015, 19 people in South Korea have died from this outbreak, with 184 confirmed cases of infection.[72] There have been at least 6508 quarantined.[73][74][75][76][77][78]

Philippines

In April 2014, MERS emerged in the Philippines with a suspected case of a home-bound Overseas Filipino Worker (OFW). Several suspected cases involving individuals who were on the same flight as the initial suspected case are being tracked but are believed to have dispersed throughout the country. Another suspected MERS-involved death in Sultan Kudarat province caused the Department of Health (DOH) to put out an alert.[79][80][81][82] On 6 July 2015 the DOH confirmed the second case of MERS in the Philippines. A 36-year-old male foreigner from the Middle East was tested positive.[83]

United Kingdom

On 27 July 2015, the accident and emergency department at Manchester Royal Infirmary closed after two patients were treated for suspected MERS virus.[84] The facility was reopened later that evening, and it was later confirmed by Public Health England that the two patients had in fact tested negative for the disease.[85]

Kenya

In January 2016 a larger outbreak of MERS among camels in Kenya is reported.[86] As of 5 February 2016 more than 500 camels are said to have died of the disease.[87] On 12 February 2016 the disease was reported to be MERS.[88] There are as of 12 February 2016 no known human cases. Antibodies though have been shown in healthy humans in Kenya according to one study.[89]

Comparisons

Comparison of Saudi Arabia and South Korean outbreak of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection.[90]

| Saudi Arabia outbreak | South Korea outbreak | |

|---|---|---|

| Geographical location | Middle East Asia | Far East Asia |

| City/Province | Riyadh, Jeddah | Seoul, Daejeon, Gyeonggi province |

| Period | 11 Apr - 9 June 2014 | 4 May - Present (15 June), 2015 |

| Overall case number | 402 | 150 |

| Health-care personnel (%) | 27% | 17% |

| Main transmission routes | Health-care center associated | Health-care center associated |

| Previous MERS case before outbreak | Yes | No |

| Types of secondary exposure who were not health-care personnel | ||

| Admission to health-care facility | 34% | 30% |

| Emergency department | 8% | 49% |

| Visit to patient at health-care facility | 17% | 29% |

| Annual outpatient department visit (per individual) | 4.5 | 14.6 |

| Annual number of hospital admission (per 100 individuals) | 10.5 | 16.1 |

History

Collaborative efforts were used in the identification of the MERS-CoV.[91] Egyptian virologist Dr. Ali Mohamed Zaki isolated and identified a previously unknown coronavirus from the lungs of a 60-year-old Saudi Arabian man with pneumonia and acute renal failure.[4] After routine diagnostics failed to identify the causative agent, Zaki contacted Ron Fouchier, a leading virologist at the Erasmus Medical Center (EMC) in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, for advice.[92] Fouchier sequenced the virus from a sample sent by Zaki.

Fouchier used a broad-spectrum "pan-coronavirus" real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) method to test for distinguishing features of a number of known coronaviruses (such as OC43, 229R, NL63, and SARS-CoV), as well as for RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), a gene conserved in all coronaviruses known to infect humans. While the screens for known coronaviruses were all negative, the RdRp screen was positive.[91]

On 15 September 2012, Dr. Zaki's findings were posted on ProMED-mail, the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases, a public health on-line forum.[9]

The United Kingdom's Health Protection Agency (HPA) confirmed the diagnosis of severe respiratory illness associated with a new type of coronavirus in a second patient, a 49-year-old Qatari man who had recently been flown into the UK. He died from an acute, serious respiratory illness in a London hospital.[91][93] In September 2012, the UK HPA named it the London1 novel CoV/2012 and produced the virus' preliminary phylogenetic tree, the genetic sequence of the virus[94] based on the virus's RNA obtained from the Qatari case.[5][95]

On 25 September 2012, the WHO announced that it was "engaged in further characterizing the novel coronavirus" and that it had "immediately alerted all its Member States about the virus and has been leading the coordination and providing guidance to health authorities and technical health agencies."[96] The Erasmus Medical Center (EMC) in Rotterdam "tested, sequenced and identified" a sample provided to EMC virologist Ron Fouchier by Ali Mohamed Zaki in November 2012.[97]

On 8 November 2012 in an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Zaki and co-authors from the Erasmus Medical Center published more details, including a tentative name, Human Coronavirus-Erasmus Medical Center (HCoV-EMC), the virus’s genetic makeup, and closest relatives (including SARS).[4]

In May 2013, the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses adopted the official designation, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which was adopted by WHO to "provide uniformity and facilitate communication about the disease."[98] Prior to the designation, WHO had used the non-specific designation 'Novel coronavirus 2012' or simply 'the novel coronavirus'.[99]

References

- ↑ Richard Lloyd Parry (10 June 2015). "Travel alert after eighth camel flu death". The Times. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)". World Health Organization. June 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Zumla, A; Hui, DS; Perlman, S (3 June 2015). "Middle East respiratory syndrome.". Lancet (London, England). 386: 995–1007. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60454-8. PMID 26049252.

- 1 2 3 4 Zaki, Ali Mohamed; van Boheemen, Sander; Bestebroer, Theo M.; Osterhaus, Albert D.M.E.; Fouchier, Ron A.M. (8 November 2012). "Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (19): 1814–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. PMID 23075143.

- 1 2 Doucleef, Michaeleen (26 September 2012). "Scientists Go Deep On Genes Of SARS-Like Virus". NPR. Associated Press. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 Assiri, Abdullah; et al. (9 September 2013). "Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 13: 752–761. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4.

- 1 2 Assiri, A.; et al. (8 January 2013). "Hospital Outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus". NEJM. 369: 407–416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ "Interim Guidance - Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infections when novel coronavirus is suspected: What to do and what not to do" (PDF). WHO. 2 November 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- 1 2 Saey, Tina Hesman (27 February 2013). "Scientists race to understand deadly new virus: SARS-like infection causes severe illness, but may not spread quickly". Science News. 183 (6). p. 5. doi:10.1002/scin.5591830603.

- ↑ "MERS Coronaviruses in Dromedary Camels, Egypt". June 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "See Also". ProMED-mail. 20 September 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Hemida, MG; et al. (12 December 2013). "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus seroprevalence in domestic livestock in Saudi Arabia". Eurosurveillance. 18 (50).

- ↑ Briese, T.; et al. (29 April 2014). "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Quasispecies That Include Homologues of Human Isolates Revealed through Whole-Genome Analysis and Virus Cultured from Dromedary Camels in Saudi Arabia". mBio. 5: e01146–14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01146-14. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ Gallagher, James (5 June 2014). "Camel infection 'led to Mers death'". BBC News. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ Azhar, E. I.; et al. (4 June 2014). "Evidence for Camel-to-Human Transmission of MERS Coronavirus". NEJM. 370: 2499–2505. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401505. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ↑ "WHO warns about camel products, contact over rising MERS concerns | CTV News". CTV News. 10 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Mers virus: Saudis warned to wear masks near camels". BBC News. 11 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia: Farmers flout Mers warning by kissing camels". BBC News. 13 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 The Health Protection Agency (HPA) UK Novel Coronavirus Investigation team (14 March 2013). "State of Knowledge and Data Gaps of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Humans". Eurosurveillance. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.0bf719e352e7478f8ad85fa30127ddb8. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ "Rapid advice note on home care for patients with Mi ddle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infecti on presenting with mild symptoms and management of contacts" (PDF). WHO. 8 August 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ Cauchemez, S.; et al. (January 2014). "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: quantification of the extent of the epidemic, surveillance biases, and transmissibility". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 14: 50–56. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70304-9. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- 1 2 "Revised interim case definition for reporting to WHO – Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)". WHO. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ↑ "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS): Case definitions". CDC. 9 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.(an outdated version)

- ↑ "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS): Case definitions". CDC. 10 April 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Laboratory Testing for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus" (PDF). WHO. September 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- 1 2 Corman, V M; et al. (27 September 2012). "Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction". Eurosurveillance. 17 (39). PMID 23041020.

- 1 2 Corman, V M; et al. (6 December 2012). "Assays for laboratory confirmation of novel human coronavirus (hCoV-EMC) infections". Eurosurveillance. 17 (49). PMID 23231891.

- ↑ Lu, Xiaoyan; et al. (1 January 2014). "Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR Assay Panel for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 52: 67–75. doi:10.1128/JCM.02533-13. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ Reusken, C; et al. (4 April 2013). "Specific serology for emerging human coronaviruses by protein microarray". Eurosurveillance. 18 (14): 20441. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.14.20441. PMID 23594517. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- 1 2 "Infection prevention and control during health care for probable or confirmed cases of novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection" (PDF). WHO. 5 June 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ Kwon H., Chan; Poon, Leo L.L.M.; Cheng, V.C.C.; et al. (February 2004). "Detection of SARS coronavirus in patients with suspected SARS.". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (2): 294–9. doi:10.3201/eid1002.030610. PMC 3322905

. PMID 15030700.

. PMID 15030700. - ↑ Jiang, Shibo; Lu, Lu; Du, Lanying (2013). "Development of SARS Vaccines and Therapeutics Is Still Needed". Medscape. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ Butler, Declan (3 October 2012). "SARS veterans tackle coronavirus". Nature (journal). 490 (7418). p. 20.

- ↑ Parrish, R. (7 June 2013). "Novavax creates MERS-CoV vaccine candidate". Vaccine News Daily. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ↑ Price, J. R. (26 June 2013). "Greffex Does It Again". Business Wire. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ Zumla A, Chan JF, Azhar EI, Hui DS, Yuen KY (2016). "Coronaviruses - drug discovery and therapeutic options". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 15: 327–47. doi:10.1038/nrd.2015.37. PMID 26868298.

- ↑ Falzarano, D; et al. (October 2013). "Treatment with interferon-α2b and ribavirin improves outcome in MERS-CoV-infected rhesus macaques". Nature Medicine. 19 (10): 1313–1317. doi:10.1038/nm.3362. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ Al-Tawfiq, J; et al. (March 2014). "Ribavirin and interferon therapy in patients infected with the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: an observational study". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 20: 42–46. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2013.12.003. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ Spanakis N, Tsiodras S, Haagmans BL, Raj VS, Pontikis K, Koutsoukou A, Koulouris NG, Osterhaus AD, Koopmans MP, Tsakris A (Dec 2014). "Virological and serological analysis of a recent Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection case on a triple combination antiviral regimen". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 44 (6): 528–32. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.07.026. PMID 25288266.

- ↑ Ren, Z; et al. (April 2013). "The newly emerged SARS-Like coronavirus HCoV-EMC also has an "Achilles' heel"". Protein & Cell. 4: 248–250. doi:10.1007/s13238-013-2841-3. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ Kindrachuk J, Ork B, Hart BJ, Mazur S, Holbrook MR, Frieman MB, Traynor D, Johnson RF, Dyall J, Kuhn JH, Olinger GG, Hensley LE, Jahrling PB (Feb 2015). "Antiviral potential of ERK/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling modulation for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection as identified by temporal kinome analysis". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 59 (2): 1088–99. doi:10.1128/AAC.03659-14. PMID 25487801.

- ↑ Otrompke, John; et al. (20 October 2014). "Investigating treatment strategies for the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus". The Pharmaceutical Journal. 293 (7833). Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ Cheng KW, Cheng SC, Chen WY, Lin MH, Chuang SJ, Cheng IH, Sun CY, Chou CY (Mar 2015). "Thiopurine analogs and mycophenolic acid synergistically inhibit the papain-like protease of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus". Antiviral Research. 115: 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.12.011. PMID 25542975.

- ↑ Chan JF, Lau SK, To KK, Cheng VC, Woo PC, Yuen KY (Apr 2015). "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease". Clin Microbiol Rev. 28 (2): 465–522. doi:10.1128/CMR.00102-14. PMID 25810418.

- ↑ Zhou Y, Vedantham P, Lu K, Agudelo J, Carrion R Jr, Nunneley JW, Barnard D, Pöhlmann S, McKerrow JH, Renslo AR, Simmons G (Apr 2015). "Protease inhibitors targeting coronavirus and filovirus entry". Antiviral Res. 116: 76–84. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.01.011. PMID 25666761.

- ↑ Báez-Santos YM, St John SE, Mesecar AD (Mar 2015). "The SARS-coronavirus papain-like protease: structure, function and inhibition by designed antiviral compounds". Antiviral Res. 115: 21–38. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.12.015. PMID 25554382.

- ↑ "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Saudi Arabia". World Health Organization. 11 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 "Severe respiratory disease associated with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV); Fifteenth update, 8 March 2015" (PDF) (PDF). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 8 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ "Statistics As of 12 pm June 11, 2015". Command & Control Center, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "MERS death count up to 29". HiDoc. 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) summary and literature update–as of 20 January 2014" (PDF) (PDF). World Health Organization. 20 January 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ Lisa Schnirring (21 January 2014). "US detects 2nd MERS case; Saudi Arabia has 18 more". Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ "Second Dutchman infected with lung virus MERS". NRC Handelsblad. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ↑ "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Turkey". World Health Organization. 24 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ "Egypt detects first case of MERS virus". Press TV. 26 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ↑ "Lebanon Records First Case of MERS Virus". Associated Press. Time. 9 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ↑ "Thailand confirms first case of deadly Mers virus". Bangkok Post. 18 June 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ McNeil Jr., Donald G. (4 June 2014). "Saudi Arabia: MERS total revised". New York Times. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ "Saudi reports 2 more deaths from Mers virus, taking toll to 94- Khaleej Times". Khaleej Times. Agence France-Presse. 27 April 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ McDowall, Angus (27 April 2014). "Saudi Arabia has 26 more cases of MERS virus, 10 dead- Reuters". Reuters. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ "Another 18 MERS Cases Identified In Saudi Arabia As Disease Spreads". The Huffington Post. Reuters. 8 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ McKenna, Maryn. "MERS Cases Increasing in Saudi Arabia, And The Hajj Is Coming". National Geographic. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ↑ "Hajj and Umrah in Saudi Arabia". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ↑ Stobbe, Mike (2 May 2014). "CDC Confirms First Case of MERS in US". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

- ↑ McKay, Betsy (3–4 May 2014). "American Returns from Mideast With MERS Virus". The Wall Street Journal. pp. A3.

- ↑ "CDC announces second imported case of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in the United States" (Press release). CDC. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ Santich, Kate (12 May 2014). "1st MERS case reported in Central Florida". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "1st MERS case reported in the Netherlands". Chicago Tribune. 14 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Aleccia, Jonel (17 May 2014). "Illinois Man is Third U.S. MERS Infection, CDC Says". NBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ Szabo, Liz (2 June 2015). "South Korean MERS outbreak likely to spread, health officials say". USA Today.

- ↑ "我国确诊首例输入性MERS病例". Xinhua News Agency (in Chinese). 30 May 2015.

- ↑ "MERS forces total sealing off of two hospitals". 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Park, Ju-min; Pomfret, James (8 June 2015). "REFILE-UPDATE 2-Hong Kong to issue "red travel alert" to South Korea as MERS spreads". Reuters. (Article published in Eastern Daylight Time)

- ↑ "South Korea Reports Third Death as MERS Cases Rise". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ↑ "14 more MERS cases identified in South Korea". Today Online. 8 June 2015.

- ↑ "Fifth Mers death in South Korea". Independent. 7 June 2015.

- ↑ "메르스 확진자 23명(이 중 D의료기관 17명) 추가 발생" [MERS infections increased by 23] (in Korean). Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare. 8 June 2015.

- ↑ "韩国MERS隔离对象增至2361人 另有560人解除隔离" [Korea increased quarantined objects MERS 2361 and another 560 people who lift the quarantine] (in Chinese). NetEase. 7 June 2015.

- ↑ del Callar, Michaela (24 April 2014). "3 of 5 quarantined Pinoys in UAE tested negative for MERS-CoV- Pinoy Abroad- GMA News Online". GMA Network. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ Fernandez, Amanda (24 April 2014). "DOH: Only 6 Etihad EY 0424 passengers left who cannot be contacted- News- GMA News Online". GMA Network. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ "OFWs from UAE quarantined in GenSan, Sarangani for possible MERS infection- MindaNews". MindaNews. 22 April 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ Lee-Brago, Pia (18 September 2013). "First Pinay dies from MERS virus- Headlines, News, The Philippine Star- philstar.com". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ "DOH confirms MERS case in PH". 6 July 2015.

- ↑ "Manchester Royal Infirmary A&E unit closed over virus outbreak". BBC News. 27 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ↑ Amy Glendinning (28 July 2015). "Two patients in Manchester test negative for MERS virus". men.

- ↑ "Mysterious disease kills camels in Marsabit". Daily Nation. 25 January 2016.

- ↑ "Anger in the north as mysterious disease wipe out camels". The Star, Kenya.

- ↑ "Camels in Kenya test positive for MERS virus". Informer East Africa.

- ↑ "MERS antibody shows promise in rabbits; signs of infection noted in Kenyans". CIDRAP.

- ↑ "Re: Why the panic? South Korea's MERS response questioned". www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h3403/rr. 2 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 Lu, Guangwen; Liu, Di; et al. (2012). "SARS-like virus in the Middle East: A truly bat-related coronavirus causing human diseases" (PDF). Protein & Cell. 3 (11): 803–805. doi:10.1007/s13238-012-2811-1.

- ↑ Butler, Declan (15 January 2013). "Tensions linger over discovery of coronavirus". Nature (journal). Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Acute respiratory illness associated with a new virus identified in the UK" (Press release). Health Protection Agency (HPA). 23 September 2012.

- ↑ Roos, Robert (25 September 2013). UK agency picks name for new coronavirus isolate (Report). University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy (CIDRAP).

- ↑ "How threatening is the new coronavirus?". BBC. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ↑ "Novel coronavirus infection" (Press release). WHO. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ↑ Heilprin, John (23 May 2013). "WHO: Probe into deadly coronavirus delayed by sample dispute". CTV News (Canada). Geneva. AP.

- ↑ "Novel coronavirus update—new virus to be called MERS-CoV" (Press release). WHO. 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "Global Alert and Response (GAR): Novel coronavirus infection - update" (Press release). WHO. 23 November 2012.