Michael Shiner

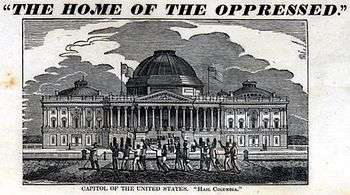

Michael G. Shiner (1805–1880) was an African-American Navy Yard worker and diarist who chronicled events in Washington D.C for more than 60 years, first as a slave and later as a free man. His diary entries have provided historians a first hand account of the War of 1812, the British Invasion of Washington, the burning of the U.S. Capitol and Navy Yard, and the rescue of his family from slavery as well as shipyard working conditions, racial tensions and other issues and events of 19th century military and civilian life.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Early life and education

Shiner was born into slavery in 1805 and grew up near Piscataway, Maryland, working on a farm called "Poor Man's Industry" that belonged to William Pumphrey Jr. At the age of eight or nine, Shiner began writing in his diary, which he continued until he was seventy-three. He used his own phonetic spelling and little punctuation. Because literacy for blacks outside of religious instruction was discouraged at the time, it is not known with certainty how Shiner learned to read and write. Historians have speculated that he may have learned from a small school at the Navy Yard run by white abolitionists.[4]

In 1814, during the War of 1812, Shiner wrote in his diary of watching the British invasion of Washington DC. "They looked like flames of fire, all red coats and the stocks of their guns painted with red vermillion, and the iron work shined like a Spanish dollar." When he and a companion began to run, he wrote, they were stopped by an older white woman, who scolded them. "Where are you running you nigger you? What do you think the British want with such a nigger as you?" Shiner's friend hid in a baking oven, but Shiner continued to watch the events unfold.[7] As the war continued, Shiner described what he saw and learned in great detail.

In his early twenties, he also attended a Sunday school run by the First Presbyterian Church of Washington at the foot of Capitol Hill which had opened for free and enslaved blacks in 1826. Shiner generally kept his writing abilities secret, and wrote very little of a personal nature in his diary, describing instead the events around him.[4]

Marriage and family

About 1828 Shiner married a 20-year-old woman named Phillis, who had been purchased at the age of nine by William Pumphrey's brother James who also worked and lived in Washington DC. The young couple lived together near the Naval yard and had six children. The Shiners regularly attended the Ebenezer Methodist Church where they took part in church adult classes for free and enslaved black people.[4]

Work at the Navy Yard

From 1800-1830 the Washington Navy Yard was the District's main employer of enslaved African Americans. In 1808, muster lists show they made up one third of the workforce. The number of enslaved workers gradually declined during the next thirty years. William Pumphrey, like many slave holders, rented his enslaved workers to the Navy Yard. In the “Muster Book of the U.S. Navy in Ordinary at the Navy Yard Washington City, Shiner is recorded as “Ordinary Seaman” with the notation he was first entered on the Ordinary rolls 1 July 1826.[4]

In the early nineteenth century shipyard, the Ordinary was where naval ships were held in reserve, or for later need. Ships in Ordinary normally were older ships awaiting restoration that had minimal crews of semi-retired or disabled sailors who remained on board to make sure that the vessels were kept in usable condition, provided security, kept the bilge pump operating, and ensured the lines were secure. Here enslaved African Americans worked as seamen, cooks, servants or laborers, performing many of the most unpleasant and difficult jobs. The work they did included scraping the hull, moving timber, and helping to suppress fires. Their wages were paid directly to their owners.[4]

In his diary, Shiner, who worked as a painter, chronicled the daily routine at the Navy Yard, providing important details of early working conditions and social attitudes at the Yard toward slaves and freeman. He tells of one incident where he was surrounded by a mob of thugs who "lit me up torch fashion with firecrackers" and another where he had to flee a gang of sailors who mistook him for a runaway slave. Other incidents he recounted included nearly drowning after falling in the freezing water and seeing a fellow worker accidentally decapacitated while working.[8] Shiner also described military/civilian relationships and the efforts of early federal workers for better pay and employment conditions, including the labor strike of 1835, which disintegrated into the Snow riots, a race riot of whites against blacks that was finally brought under control by President Andrew Jackson and the U.S. Marines. In his diary, Shiner wrote about how a group of white Yard mechanics went after a black restaurant owner named Snow and threatened to attack Commodore Hull: "all the Mechanics of classes gathered into snows Restaurant and broke him up Root and Branch and they were after snow but he flew for his life and that night after they had broke snow up they threatened to come to the navy yard after commodore Hull."[4]

Slavery and freedom

When Shiner's owner William Pumphrey died in 1827, he stipulated in his will that all his slaves were to be sold as 'term slaves' for a specific period of time, and afterwards manumitted. Michael Shiner was to be freed after another fifteen years of slavery. He was bought by Thomas Howard, clerk of the Navy Yard in 1828 for $250. When Howard died in 1832, his will stipulated that Shiner be set free in 1836. In March 1833, his wife Phillis's owner James Pumphrey died, and Shiner writes in his diary that his wife and the children “wher snacht away from me and sold” on the street of Washington by slave dealers and confined to a slave pen in Alexandria. After a few weeks, Shiner was able, with help from wealthy and powerful connections, including Commodore Hull, to gain the release of Phillis and the children and to secure their manumission. However, Shiner himself remained enslaved. On 26 March 1836 in the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia he filed a petition for freedom, declaring that he was “ unjustly, and illegally held in bondage’ by the executors of Thomas Howard’s estate Ann Nancy Howard and William E. Howard. By 1840, Michael Shiner and his family were listed in the census as "free colored". As a freeman he continued to work at the Navy Yard as a painter where he was able to save money and provide for his family.[4]

Later life

Shiner's wife Phillis died some time before 1849. In 1850 he was living in Washington DC with his second wife Jane, aged 19, and children Sarah, Isaac and Braxton. After the Civil War, Shiner prospered, was active in the Republican Party and became an outspoken champion of black rights. Shiner worked at the Navy Yard until some time after 1870. In his later years, it is believed he may have expanded upon some of the early entries in his diary, adding specifics which he did not know as a child.[4]

Death and legacy

Shiner died of smallpox on January 16, 1880. He was buried in the Union Beneficial Association Cemetery on C Street. The newspaper the Evening Star published a front page obituary of Shiner, writing that he had “the most retentive memory of anyone in the city, being able to give the name and date of every event which came under his observation, even in his boyhood.” After his death, his diary came into the possession of the Library of Congress. In it, the donor wrote: "This book is a very valuable book and is very interesting. It is worthy of perusal. The author Michael Shiner was a Patriot may he rest in peace."[4]

References

- ↑ "Slavery and the Making of America: The Diary of Michael Shiner", PBS.org

- ↑ Civil War in America: Biography of Michael Shiner, Library of Congress Exhibitions

- ↑ Tonya Bolden, Capital Days: Michael Shiner's Journal and the Growth of Our Nation's Capital, Harry N. Abrams, Jan 6, 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 John G. Sharp, "The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869, Naval History and Heritage Command, 2015, retrieved October 5, 2016

- ↑ Robert Pohl: "Lost Capitol Hill: False Accusations", The Hill is Home, retrieved October 5, 2016

- ↑ Leslie Anderson, The Life of Freed Slave Michael Shiner, American History TV, C-Span

- 1 2 Steve Vogel, Through the Perilous Fight: Six Weeks That Saved the Nation, Random House, May 7, 2013 p. 165

- ↑ J.D. Dickey, "Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington, D.C", Rowman and Littlefield, 2014, p. 128