Miami people

|

Kee-món-saw, Little Chief, Miami chief, painted by George Catlin, 1830 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (3,908 (2011)[1]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Miami-Illinois | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Traditional tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Peoria, Kaskaskia, Piankashaw, Wea, Illinois, and other Algonquian peoples |

The Miami (Miami-Illinois: Myaamiaki) are a Native American nation originally speaking one of the Algonquian languages. Among the peoples known as the Great Lakes tribes, it occupied territory that is now identified as Indiana, southwest Michigan, and western Ohio. By 1846, most of the Miami had been removed to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma is the only federally recognized tribe of Miami Indians in the United States. The Miami Nation of Indiana is an unrecognized tribe.

Name

The name Miami derives from Myaamia (plural Myaamiaki), the tribe's autonym (name for themselves) in their Algonquian language of Miami-Illinois. This appears to have been derived from an older term meaning "downstream people." Some scholars contended the Miami called themselves the Twightwee (also spelled Twatwa), supposedly an onomatopoeic reference to their sacred bird, the sandhill crane. Recent studies have shown that Twightwee derives from the Delaware language exonym for the Miamis, tuwéhtuwe, a name of unknown etymology.[2] Some Miami have stated that this was only a name used by other tribes for the Miami, and not their autonym. They also called themselves Mihtohseeniaki (the people). The Miami continue to use this autonym today.

| Name | Source[3] | Name | Source[3] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maiama | Maumee | later French | ||

| Meames | Memilounique | French | ||

| Metouseceprinioueks | Myamicks | |||

| Naked Indians | Nation de la Grue | French | ||

| Omameeg | Omaumeg | Chippewa | ||

| Oumami (or Oumiami) | Oumamik | 1st French | ||

| Piankashaw | Quikties | |||

| Tawatawas | Titwa | |||

| Tuihtuihronoons | Twechtweys | |||

| Twightwees | Delaware | Wea | band | |

History

Prehistory

| 1654 | Fox River, southwest of Lake Winnebago |

|---|---|

| 1670-95 | Wisconsin River, below the Portage to the Fox River |

| 1673 | Niles, Michigan |

| 1679-81 | Fort Miamis, at St. Joseph, Michigan |

| 1680 | Fort Chicago |

| 1682-2014 | Fort St. Louis, at Starved Rock, Illinois |

| 1687 | Calumet River, at Blue Island, Illinois |

| c. 1691 | Wabash River, at the mouth of the Tippecanoe River |

| [4][5] | |

Early Miami people are considered to belong to the Fischer Tradition of Mississippian culture.[6] Mississippian societies were characterized by maize-based agriculture, chiefdom-level social organization, extensive regional trade networks, hierarchical settlement patterns, and other factors. The historical Miami engaged in hunting, as did other Mississippian peoples.

During historic times, the Miami were known to have migrated south and eastwards from Wisconsin from the mid-17th century to the mid-18th century, by which time they had settled on the upper Wabash River in what is now northwestern Ohio. The migration was likely a result of their being invaded during the protracted Beaver Wars by the more powerful Iroquois, who traveled far in strong organized groups (war parties) from their territory in central and western New York for better hunting during the peak of the eastern beaver fur trader days. The Dutch and French traders and, after 1652, the British fueled demand. The warfare and social disruption contributed to the decimation of Native American populations, but the major factor were fatalities from infectious diseases for which they had no immunity. These are believed to have reduced the populations by ninety percent.

Historic locations[3]

| Year | Location |

|---|---|

| 1658 | Northeast of Lake Winnebago, WI (Fr) |

| 1667 | Mississippi Valley of Wisconsin |

| 1670 | Head of the Fox River, WI; Chicago village |

| 1673 | St. Joseph River Village, MI (River of the Miamis) (Fr), |

| Kalamazoo River village, MI | |

| 1703 | Detroit village, MI |

| 1720-63 | Miami River locations, OH; |

| Scioto River village (nr Columbus), OH | |

| 1764 | Wabash River villages |

European contact

When French missionaries first encountered the Miami in the mid-17th century, the indigenous people were living around the western shores of Lake Michigan. The Miami had reportedly moved there because of pressure from the Iroquois further east. Early French explorers noticed many linguistic and cultural similarities between the Miami bands and the Illiniwek, a loose confederacy of Algonquian-speaking peoples.

At this time, the major bands of the Miami were:

- Atchakangouen (also Atchatchakangouen or Greater Miami)

- Kilatika

- Mengkonkia (Mengakonia)

- Pepikokia (Kithtippecanuck)

- Piankeshaw (Newcalenous)[8]

- Wea (Ouiatenon)[9]

In 1696, the Comte de Frontenac appointed Jean Baptiste Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes as commander of the French outposts in northeast Indiana and southwest Michigan. He befriended the Miami people, settling first at the St. Joseph River, and, in 1704, establishing a trading post and fort at Kekionga, present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana.[10]

By the 18th century, the Miami had for the most part returned to their homeland in present-day Indiana and Ohio. The eventual victory of the British in the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War) led to an increased British presence in traditional Miami areas.

Shifting alliances and the gradual encroachment of European-American settlement led to some Miami bands merging. Native Americans created larger tribal confederacies led by Chief Little Turtle; their alliances were for waging war against Europeans and to fight advancing white settlement. By the end of the century, the tribal divisions were three: the Miami, Piankeshaw, and Wea.

The latter two groups were closely aligned with some of the Illini tribes. The US government later included them with the Illini for administrative purposes. The Eel River band maintained a somewhat separate status, which proved beneficial in the removals of the 19th century. The nation's traditional capital was Kekionga.

Locations

- 1718-94 Kekionga, Portage of the Maumee and Wabash rivers, Fort Wayne, Indiana

- 1720-49 Portage of the Miami River, St. Joseph and Kankakee rivers

- unknown - 1733 Tepicon of the Wabash, Fort Ouiatenon, Lafayette, Indiana

- 1733-51 Tepicon of the Tippecanoe, headwaters of the Tippecanoe River near Warsaw

- 1748-52 Pickawillany, Piqua on the Great Miami River in Ohio

- 1752 Headwaters of the Eel River, southwest of Columbia City, Indiana

- 1752 Le Gris, Maumee River (Miami River), east of Fort Wayne

- 1763 Captured British at Fort Miami (1760–63) as a part of the Pontiac’s Rebellion

- 1774 Warriors participated in Lord Dunmore's War in Ohio

- 1778 Kenapacomaqua, Wabash at the mouth of the Eel River, Logansport, Indiana

- 1780 October — Agustin Mottin de La Balme (French, from St. Louis) headed a raid of Detroit. Stopped and destroyed Kekionga. La Balme withdrew to the west, where Little Turtle destroyed the raiders, killing one third of them, on the 5th of November.

United States and Tribal Divide

The Miami had mixed relations with the United States. Some villages of the Piankeshaw openly supported the American rebel colonists during the American Revolution, while the villages around Ouiatenon were openly hostile. The Miami of Kekionga remained allies of the British, but were not openly hostile to the United States (US) (except when attacked by Augustin de La Balme in 1780).

The U.S. government did not trust their neutrality, however. US forces attacked Kekionga several times during the Northwest Indian War shortly after the American Revolution. Each attack was repulsed, including the battle known as St. Clair's Defeat, recognized as the worst defeat of an American army by Native Americans in U.S. history.[11] The Northwest Indian War ended with the Battle of Fallen Timbers and Treaty of Greenville. Those Miami who still resented the United States gathered around Ouiatenon and Prophetstown, where Shawnee Chief Tecumseh led a coalition of Native American nations. Territorial governor William Henry Harrison and his forces destroyed Prophetstown in 1811, having used the War of 1812 as pretext for attacks on Miami villages throughout the Indiana Territory.

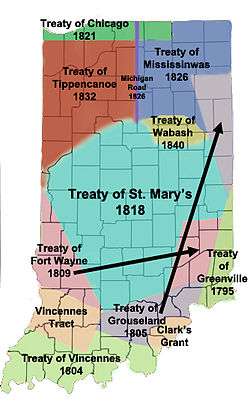

The Treaty of Mississinwas, signed in 1826, forced the Miami to cede most of their land to the US government. It also allowed Miami lands to be held as private property by individuals, where the tribe had formerly held the land in common. At the time of Indian Removal in 1846, those Miami who held separate allotments of land were allowed to stay as citizens in Indiana. Those who affiliated with the tribe were moved to reservations west of the Mississippi River, first to Kansas, then to Indian Territory in Oklahoma.

The divide in the tribe exists to this day. The U.S. government has recognized the Western Miami as the official tribal government since the forced divide in 1846. Migration between the tribes has made it difficult to track affiliations and power for bureaucrats and historians alike.[12] Today the western tribe is federally recognized as the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, with 3553 enrolled members.

The Eastern Miami (or Indiana Miami) has its own tribal government, but lacks federal recognition. Although they were recognized by the US in an 1854 treaty, that recognition was stripped in 1897. In 1980, the Indiana legislature recognized the Eastern Miami and voted to support federal recognition.[13] In the late 20th century, US Senator Richard Lugar introduced a bill to recognize the Eastern Miami. He withdrew support due to constituent concerns over gambling rights. In recent decades, numerous federally recognized tribes in other states have established gambling casinos and related facilities on their sovereign lands.[14] Such establishments have helped some tribes raise revenues to devote to economic development, health and education. On 26 July 1993, a federal judge ruled that the Eastern Miami were recognized by the US in the 1854 treaty, and that the federal government had no right to strip them of their status in 1897. However, he also ruled that the statute of limitations on appealing their status had expired. The Miami no longer had any right to sue.[15]

Locations

- 1785 – Delaware villages located near Kekionga (refugees from American settlements)

- 1790 – Pickawillany Miami join Kekionga (refugees from American settlements)

- 1790 Gen. Harmar marches on Kekionga to punish the Miami, Delaware, and Shawnee villages. On October 17, Harmar found the seven villages deserted. The rear guard, left to destroy the returning villagers, was defeated by Little Turtle's warriors.

- 1790 – Mississinewa (Mississinewa River below the Wabash, southeast of Peru, Indiana)

- 1791 Gen. Arthur St. Clair moves on Kekionga. Little Turtle destroys the US Army (1400) near the future Fort Recovery.

- Kentucky Militia destroy Eel River villages.

- 1793 December — General Anthony Wayne moves to Fort Recovery to prepare to destroy Kekionga.

- 1794 August — Fort Defiance (Defiance, Ohio) built on the Maumee River, site of deserted Shawnee village of Blue Jacket. 20 August Battle of Fallen Timbers, Blue Jacket loses to Wayne.

- 1794 – Kekionga site abandoned

- Mississinewa towns become the center of the nation.

- 1809 – Gov. William Henry Harrison orders destruction of all villages within two days' march of Fort Wayne. Villages near Columbia City and Huntington destroyed.

- 17 December – Lt. Col. John B. Campbell ordered to destroy the Mississinewa villages. Campbell destroys villages and kills women and children.

- 18 December, at second village, Americans repulsed and return to Greenville.

- 1810 July – US Army returns and burns deserted town and crops.

- 1817 Maumee Treaty — loose Ft. Wayne area (1400 Miami counted)

- 1818 Treaty of St. Mary’s (New Purchase Treaty) - lose south of the Wabash — Big Miami Reservation created. Grants on the Mississinewa and Wabash given to Josetta Beaubien, Anotoine Bondie, Peter Labadie, Francois Lafontaine, Peter Langlois, Joseph Richardville, and Antoine Rivarre. Miami National Reserve (875,000) created.

- 1818 Eel River Miami settle at Thorntown, northeast of Lebanon).

- 1825 1073 Miami, including the Eel River Miami

- 1826 Mississinewa Treaty — loose between the Eel and the Wabash to create a right of way for the canal. Eel River Miami leave Thorntown, northeast of Lebanon, for Logansport area.

- 1834 Western part of the Big Reservation sold (208,000 acres (840 km2))

- 1838 Potawatomi removed from Indiana. No other Indian tribes in the state. Treaty of 1838 made 43 grants and sold the western portion of the Big Reserve. Richardville exempted from any future removal treaties. Richardsville, Godfroy, Metocina received grants, plus family reserves for Ozahshiquah, Maconzeqyuah (Wife of Benjamin), Osandian, Tahconong, and Wapapincha.

- 1840 Remainder of the Big Reservation (500,000 acres (2,000 km2)) sold for lands in Kansas. Godfroy descendants and Meshingomesia (s/o Metocina), sister, brothers and their families exempted from the removal. 800 Miami

- 1846 – October 1, removal was supposed to begin. It began October 6 by canal boat. By ship to Kansas Landing Kansas City and 50 miles (80 km) overland to the reservation. Reached by 9 November.

- 1847 Godfroy Reserve, between the Wabash and Mississinewa

- Wife of Benjamin Reserve, east edge of Godfroy

- Osandian Reserve, on the Mississinewa, southeast boundary of Godfroy

- Wapapincha Reserve, south of Mississinewa at Godfroy/Osandian juncture

- Tahkonong Reserve, southeast of Wapapincha south of Mississinewa

- Ozahshinquah Reserve, on the Mississinewa River, southeast of Peoria

- Meshingomesa Reserve, north side of Mississinewa from Somerset to Jalapa (northwest Grant County)

- 1872 Most reserves were partially sold to non-Indians.

- 1922 All reserves were sold for debt or taxes for the Miamis.

Places named for the Miami

A number of places have been named for the Miami nation. Miami, Florida is not named for the tribe, but the nearby Miami River, which is in turn named for the Mayaimi people.

Towns and Cities

Townships

|

CountiesFortsBodies of water and geographical locations

InstitutionsSports teams |

Notable Miami people

- Francis Godfroy (Palawonza), Miami Chief

- Tetinchoua, a powerful 17th-century Miami chief

- Little Turtle (Mishikinakwa), 18th-century war chief

- Pacanne, 18th-century chief

- Francis La Fontaine, last principal chief of the united Miami tribe

- Jean Baptiste de Richardville (Peshewa), 19th-century chief

- Frances Slocum (Maconaquah), adopted member of the Miami tribe

- William Wells (Apekonit), adopted member of the Miami tribe

- Loni Hoots (Poet), member of the Miami tribe by birth.

Notes

- ↑ 2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory. Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. 2011: 21. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ Costa, David J. 2000. "Miami-Illinois Tribe Names", in John Nichols, ed., Papers of the Thirty-first Algonquian Conference, pp. 30-53. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba.

- 1 2 3 Great Lakes Indians; A Pictorial Guide; Kubiak, William J.; Baker Book House Company, 1970

- 1 2 3 4 Tanner, Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History

- 1 2 3 4 Rafert, The Miami Indians of Indiana

- ↑ Emerson, Thomas E. and R. Barry Lewis. Cahokia and the Hinterlands: Middle Mississippian Cultures of the Midwest, Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2000:17. ISBN 978-0-252-06878-2.

- ↑ Carter, Life and Times, 62–3.

- ↑ Baxter, pg 4

- ↑ Anson, pg 13

- ↑ "Vincennes, Sieur de (Jean Baptiste Bissot)," The Encyclopedia Americana (Danbury, CT: Grolier, 1990), 28:130.

- ↑ Sisson, Richard; Zacher, Christian; and Cayton, Andrew (eds.) (2007). The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia, p. 1749. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34886-2

- ↑ Rafert, p. XXV

- ↑ Rafert, pg. 291.

- ↑ Rafert, pg. 292

- ↑ Rafert, pg. 293.

- 1 2 Drury, Augustus Waldo (1909). History of the City of Dayton and Montgomery County, Ohio, Volume 1. S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 57.

References

- Anson, Bert (2000). The Miami Indians. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3197-7.

- Baxter, Nancy Niblack (1987). The Miamis!. Emmis books. ISBN 0-9617367-3-9.

- Magnin, Frédéric (2005). Mottin de la Balme, cavalier des deux mondes et de la liberté. Paris:: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-7475-9080-1.

- Rafert, Stewart (1996). The Miami Indians of Indiana; A Persistent People 1654-1994. Indiana Historical Society.

- Tanner, Helen Horbeck (1987). Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2056-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Miami (tribe). |

- Miami Indian Collection (MSS 004)

- Guide to Native American Resources

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Miami Indians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Miami Indians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Miami (tribe)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Miami (tribe)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

.jpg)