Metoposaurus

| Metoposaurus Temporal range: Carnian, 228–216.5 Ma | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Skeleton of Metoposaurus diagnosticus krasiejowensi in the Krasiejów museum in Poland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Temnospondyli |

| Suborder: | †Stereospondyli |

| Family: | †Metoposauridae |

| Genus: | †Metoposaurus Lydekker, 1890 |

| Species | |

|

Nomina dubia:

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus-level:

Species-level:

| |

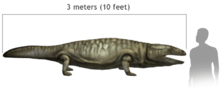

Metoposaurus (pronounced Me-top-o-sore-us)[1] meaning "front lizard" is an extinct genus of Stereospondyli temnospondyl amphibian, known from the Late Triassic of Germany, Italy, Poland, and Portugal.[2][3][4] This mostly aquatic animal possessed small, weak limbs, sharp teeth, and a large, flat head.[5] This highly flattened creature mainly fed on fish, which it captured with its wide jaws lined with needle-like teeth. Metoposaurus was up to 3 m (10 feet) long and weighed 454 kg (1,000 pounds),.[5] Many Metoposaurus mass graves have been found, probably from creatures that grouped together in drying pools during drought.

Description

Skull

Lacrimal

The lacrimal contacts the nasal medially, the maxilla laterally, the prefrontal posteromedially, and the jugal posteriorly. Metoposaur taxonomy was based on the position of lacrimal bone, and differing opinions have been published. According to photograph published by Hunt (1993), it is noted that the lacrimal enters the orbit contrary to previous finding by Fraas (1889).[3] According to Lucas, close examination of the skull and other metoposaur skulls does not support this claim and it has been noted that the misidentification was possible due to the poor preservation of fossil.[6] In 2007, Sulej noted that the variability in the position of lacrimal is narrow enough to be used for phylogeny analysis but with caution.

Parietal

Study conducted by Sulej (2007) shows that the parietal contacts the frontal anteriorly, the postfrontal anterolaterally, the supratemporal laterally, and the postparietal posteriorly. The pineal foramen is in the posterior region of the parietal. An interesting feature pointed out by Sulej on examining the skull of Metoposaurus diagnosticus krasiejowensis is that it has a shorter prepineal region of the parietal than Metoposaurus diagnosticus diagnosticus and the expansion angle of the suture separating the parietal from the supratemporal has a lower value[3]

Maxilla

Maxilla forms a large, completely dentigerous shelf bearing 83 to 107 teeth. The first teeth are large, and tooth size decreases markedly further posteriorly. On the ventral side, the maxilla contacts the ectopterygoid, palatine and vomer. In the choanal region, the maxilla is slightly broadening medially on the palatal side where it borders the choana. The margin of the choana is variable. In most skulls, it is weakly distinguished and rounded, but in a few cases it is more solid and sharply outlined.[7]

Vertebral Column

According to Sulej (2007), the intercentra of cervical and thoracic vertebra are fully ossified. The pleurocentra are not preserved and no evidence is found that they were present as cartilages. The atlas, axis, and third and fourth cervical vertebrae are characteristic and similar to those in stereospondyls. The morphology of atlas, axis, third and fourth vertebrae suggest that the neck of Metoposaurus was relatively flexible. The intercentra of the region where the vertebral column contacts the shoulder girdle are flat anteriorly and posteriorly. The neural arches have almost vertically set prezygapophyses (vide postcervical vertebrae).This suggests that in this region the lateral bending of the vertebral column was very limited. It was probably connected with articulation of the vertebral column with the shoulder girdle. A stiffening of the vertebral column, in the region of contacting limbs, was apparently essential for the swimming.He also describes that in Metoposaurus diagnosticus krasiejowensis, the parapophyses become shorter posteriorly, similarly to plagiosaurids.The intercentra of dorsal and sacral vertebrae are fully ossified and form quite short disks, not connected with the neural arches. In the dorsal and sacral region, they have anterior and posterior surfaces concave or the posterior surface is almost flat. This condition resembles that in the trunk of plesiosaurs and, to some degree, the ichthyosaurs, confirming the aquatic mode of life.[7]

Geography and History

Metoposaurids are known from the Keuper of Germany and Austria, upper Triassic of eastern and western North America, Africa, and upper Triassic of central India.[8] There have also been unconfirmed notifications reported from Madagascar (Dutuit 1978) and China (Yang 1978).[9][10][11] In the book Triassic Life on Land: The Great Transition, it is noted that Metoposaurs and its relatives were widely distributed and common throughout Laurasia during the Late Triassic.Sues;Fraser, Hans-Dieter;Nicholas (2010). Triassic Life on Land: The Great Transition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231135221. Metoposaurus diagnosticus krasiejoviensis is the most abundant metoposaurid amphibian of the Krasiejów site (the species name comes from the site) located in southern Poland.[12]

Among stereospondyls, metoposaurus seems to have been one of the latest survivors. However, a variety of other temnospondyl lines carried into the Jurassic, the latest of which was another stereospondyl, the chigutisaurid Koolasuchus, discovered in modern-day Australia, where it was supported by a colder mid-Cretaceous climate.

Discovery and Species

Discovery

The earliest mention of Metoposauridae dates back to 1842 when von Meyer (1842) descried the dorsal view of skull roof of a labyrinthodont from the Keuper Schilfsandstein of Feuerbacher Haide near Stuttgart. Later, Meyer attempted a reconstruction of the same specimen and named it Metopias diagnosticus. However, Lydekker later renamed the species as Metoposaurus diagnosticus in 1890 as the name Metopias was preoccupied.[7][13]

Species

Based on the position of lacrimal in the skull, Metoposauridae is divided into two lineages. The group with the lacrimal external to the orbit includes Buettneria bakeri, Dutuitosaurus ouazzoui, Arganasaurus lyazidi, and Apachesaurus gregorii. They show a tendency towards decreasing depth of the otic notch and a decrease in body size. Metoposaurus diagnosticus, Metoposaurus diagnosticus krasiejowensis and Metoposaurus maleriensis fall in the category of lacrimal forming the orbital margin.[7]

- Metoposaurus diagnosticus (Meyer, 1842)

Anterior top of the lacrimal more closer to the nares than the top of the prefrontal; interclavicle with posterior part longer than in Metoposaurus maleriensis.[7][14] Metoposaurus diagnosticus diagnosticus lived in the western Germanic Basin, from at least the Schilfsandstein to the Lehrberg Beds sedimentation.[11]

- Metoposaurus diagnosticus krasiejowensis (Sulaj, 2002)

Very short perineal part of the parietal with the high value of the expansion angle of the sutures separating partial from the supratemporal (mean angle value of 21.81). Some skull possess a large quadrate foramen and small paraquadrate foramen.[7]

- Metoposaurus maleriensis (Chowdhury, 1965)

Fossils were first discovered by Rev. Hislop in 1856 in the village of Maleri.[11][15]

- Metoposaurus algarvensis Brusatte et al. 2015 from the Late Triassic of Grés de Silves Fm. in Algarve, Portugal. It has broader skull than any other Metoposaurus[16]

Subspecies

- Metoposaurus stuttgartensis: first described by Fraas (1913) from the Keuper Lehbergstufe of Sonnenberg, near Stuttgart. Fraas identified the species based on the interclavicle and left clavicle, vertebrae and rib fragments which are now located in the Stuttgart Museum.[17]

- Metoposaurus santaecrucis was described by Koken (1913) based on the partial skull found in Heiligenkreuz and the specimen is now located in the University Museum of Tübingen.[18]

- Metoposaurus heimi was described by Kuhn (1932) based on a complete skull from the middle Keuper Blasensandstein in Upper Franconia. The specimen is currently located in the Museum of Paleontology and Historical Geology, Munich.[7]

Paleobiology

Mode of Swimming and Burrowing

Examining the vertebral column and limb articulations of Metoposaurs suggest that they used their limbs as flippers and swam by making simultaneous and symmetrical limb movements similar to plesiosaurs.[7] A recent study conducted in Poland suggests that the broad, flat head, broad flat arm bones, wide hands, and large tail of Metaposaurus diagnosticus is significant characteristic which led the researchers to conclude that they swam in ephemeral lakes during the wet season and used its broad, flat head and forearms to burrow under the ground when the dry season began.The study found that the medullary region is filled with well-developed trabecular bone. The growth marks in all bones are organized as thick layers of highly vascularized zones and thick compact annuli with numerous rest lines, which may correspond with favorably wet and long, unfavorably dry seasons.[19][20] However, Dr. Michel Laurin from the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle expressed concerns in the conclusions citing that the animal was much larger than the known burrowing species and hinted the possibility of snout and tail being more involved in the process.[20]

Predators

The exact predators of Metoposaurus are unknown, but phytosaurs were found closely associated in bone beds.[21]

References

- ↑ http://www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/m/metoposaurus.html

- ↑ Brusatte, S. L., Butler R. J., Mateus O., & Steyer S. J. (2015). A new species of Metoposaurus from the Late Triassic of Portugal and comments on the systematics and biogeography of metoposaurid temnospondyls. Journal of Vertebrate PaleontologyJournal of Vertebrate Paleontology. e912988., 2015:

- 1 2 3 T. Sulej, "Species discrimination of the Late Triassic temnospondyl amphibian Metoposaurus diagnosticus", Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 47, 535-546 (2002)

- ↑ Steyer, J. S., Mateus O., Butler R. J., Brusatte S. L., & Whiteside J. H. (2011) "A new metoposaurid (temnospondyl) bonebed from the Late Triassic of Portugal", Abstracts of the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, 200.

- 1 2 Gaines, Richard M. (2001). Coelophysis. ABDO Publishing Company. p. 16. ISBN 1-57765-488-9.

- ↑ Lucas, S.G. and Spielmann, J.A., eds., 2007, The Global Triassic. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sulej, T. 2007. Osteology, variability, and evolution of Metoposaurus, a temnospondyl from the Late Triassic of Poland. Palaeontologia Polonica 64, 29–139.

- ↑ Chowdhury, T. Roy. "A new metoposaurid amphibian from the Upper Triassic Maleri Formation of Central India." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 250.761 (1965): 1-52.

- ↑ Dutuit, J.M.1978. Description de quelques fragments osseux provenant de la région de Folakara (Trias supérieur Malagache). Bulletin de Museum Nationale d’Histoire naturelle, Paris. Series III 516: 79–89

- ↑ Yang, C. 1978. A Late Triassic vertebrate fauna from Fukang, Sinkiang. Memoir of the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Paleoanthropology 13, 60–67.

- 1 2 3 Sulej, T. 2007. Osteology, variability, and evolution of Metoposaurus, a temnospondyl from the Late Triassic of Poland. Palaeontologia Polonica 64, 29–139.

- ↑ Barycka, Ewa. "Morphology and ontogeny of the humerus of the Triassic temnospondyl amphibian Metoposaurus diagnosticus." Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie-Abhandlungen 243.3 (2007): 351-361.

- ↑ Chowdhury, T.R. 1965. A new metoposaurid amphibian from the Upper Triassic Maleri Formation of Central India. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 250, 1–52.

- ↑ Meyer, E. 1842. Labyrinthodonten−Genera. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geographie, Geologie, Paläontologie 1842,301–304.

- ↑ Chowdhury, T.R. 1965. A new metoposaurid amphibian from the Upper Triassic Maleri Formation of Central India. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 250, 1–52

- ↑ Brusatte, S. L., Butler R. J., Mateus O., & Steyer S. J. (2015). A new species of Metoposaurus from the Late Triassic of Portugal and comments on the systematics and biogeography of metoposaurid temnospondyls. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, e912988., 2015

- ↑ Fraas, E. 1913. Neue Labyrinthodonten aus der Schwäbischen Trias. Palaeontographica 60, 275–294

- ↑ Koken, E.1913.Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Schichten von Heiligenkreuz (Abteital, Südtirol). Abhandlungen der Kaiserlich−Koniglichen Geologischen Reichsanstalt 16: 1–44.

- ↑ Konietzko-Meier, Dorota, and Nicole Klein. "Unique growth pattern of Metoposaurus diagnosticus krasiejowensis (Amphibia, Temnospondyli) from the Upper Triassic of Krasiejów, Poland." Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 370 (2013): 145-157.

- 1 2 http://phys.org/news/2013-09-giant-triassic-amphibian-burrowing-youngster.html

- ↑ Mateus, O., Butler R. J., Brusatte S. L., Whiteside J. H., & Steyer S. J. (2014). The first phytosaur (Diapsida, Archosauriformes) from the Late Triassic of the Iberian Peninsula. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34(4), 970-975