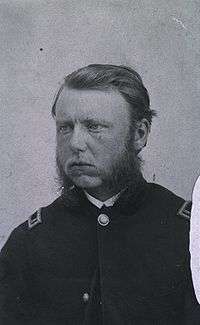

Washington Matthews

| Washington Matthews | |

|---|---|

|

Photo credit: National Library of Medicine | |

| Born |

Washington Matthews June 17, 1843 Killiney, near Dublin, Ireland |

| Died |

March 2, 1905 (aged 61) Washington, DC |

| Alma mater | University of Iowa |

| Known for | Ethnography of the Native American peoples |

Washington Matthews (June 17, 1843 – March 2, 1905) was a surgeon in the United States Army, ethnographer, and linguist known for his studies of Native American peoples, especially the Navajo.[1]

Early life and education

Matthews was born in Killiney, near Dublin, Ireland in 1843[2] to Nicolas Blayney Matthews and Anna Burke Matthews. His mother having died a few years after his birth, his father took him and his brother to the United States. He grew up in Wisconsin and Iowa, and his father, a medical doctor, began training his son in medicine. He would go on to graduate from the University of Iowa in 1864 with a degree in medicine.[3]

The American Civil War was raging at the time, and Matthews immediately volunteered for the Union Army upon graduating. His first post was as surgeon at Rock Island Barracks, Illinois, where he tended to Confederate prisoners.[3]

In the West

Matthews was posted at Fort Union in what is now Montana in 1865. It was there that an enduring interest in Native American peoples and languages took root. He would go on to serve at a series of forts in Dakota Territory until 1872: Fort Berthold, Fort Stevenson, Fort Rice, and Fort Buford.[1] He was a part of General Alfred H. Terry's expedition in Dakota Territory in 1867.[4]

While stationed at the Fort Berthold in the Dakota Territory, he learned to speak the Hidatsa language fluently, and wrote a series of works describing their culture and language: a description of Hidatsa-Mandan culture, including a grammar and vocabulary of the Hidatsa language[4] and an ethnographic monograph of the Hidatsa.[5] He also described, though less extensively, the related Mandan and Arikara peoples and languages. (Some of Matthews' work on the Mandan was lost in a fire before being published.[6])

There is some evidence that Matthews married a Hidatsa woman during this time. Her name is not known.[7] There is also speculation and circumstantial evidence that Matthews had a son with the woman.[8][9]

In 1877 he participated in an expedition against the Nez Perce, and again in 1878 against the Bannock. While serving on a prison on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, Matthews made a study of the Modoc language.[10]

Army Medical Museum

From 1884 to 1890, Matthews was posted to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, DC. During this time he conducted research and wrote several papers on physical anthropology, specifically craniometry and anthropometry.[10]

With the Navajo

John Wesley Powell of the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of American Ethnology suggested that Matthews be assigned to Fort Wingate, near what is now Gallup, New Mexico. It was there that Matthews came to know the people who would become the subject of his best known work, the Navajo.

His work on the Navajo served to dispel then-current erroneous thinking about the complexity of Navajo culture:

- Dr Matthews referred to Dr Leatherman's account of the Navahoes as the one long accepted as authoritative. In it that writer has declared that they have no traditions nor poetry, and that their songs "were but a succession of grunts." Dr. Matthews discovered that they had a multitude of legends, so numerous that he never hoped to collect them all: an elaborate religion, with symbolism and allegory, which might vie with that of the Greeks; numerous and formulated prayers and songs, not only multitudinous, but relating to all subjects, and composed for every circumstance of life. The songs are as full of poetic images and figures of speech as occur in English, and are handed down from father to son, from generation to generation.[11]

Matthews is said to have been initiated into various secret Navajo rituals.[12]

Matthews argued that the Navajo were ichthyphobic.[13]

Medical research and retirement

Matthews was quoted by Charles Darwin in his work on emotion; Matthews is cited with respect to the expression of emotion and other gestures among various peoples of America: the Dakota, Tetons, Grosventres, Mandans, and Assiniboine.[14]

Loeseliastrum matthewsii was named after him.[15]

Selected works

- Matthews, Washington (1873). Grammar and Dictionary of the Language of the Hidatsa. New York: Cramoisy Press. ISBN 978-0-404-15787-6. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Matthews, Washington (1877). Ethnography and philology of the Hidatsa Indians. United States Government Printing Office. ISBN 0-665-55834-1.

- Matthews, Washington (1887). The Mountain Chant: A Navajo Ceremony. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-60506-898-5.

- Matthews, Washington (1994) [First published 1897]. Navaho legends. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-424-8.

- Matthews, Washington (2008) [First published 1907]. Navaho Myths, Prayers and Songs. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-60506-899-2.

Matthews is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.[6]

References

- 1 2 Samuel Storrs Howe; et al. (1905). Annals of Iowa. Iowa State Historical Department. p. 155.

- ↑ Dan L. Thrapp (1991). Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: G-O. U of Nebraska Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0-8032-9419-6.

- 1 2 Mooney, James (1905). "In Memoriam: Washington Matthews". American Anthropologist. 7: 514–23. doi:10.1525/aa.1905.7.3.02a00060.

- 1 2 Matthews 1873.

- ↑ Matthews 1877.

- 1 2 Patterson, Michael Robert. "Washington Matthews, Major, United States Army". Arlington National Cemetery. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ↑ Wood, W. Raymond; Karl Bodmer; Joseph C. Porter; David C. Hunt (2002). Karl Bodmer's studio art: the Newberry Library Bodmer collection. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-252-02756-7.

- ↑ Link, Margaret Schevill (Oct–Dec 1960). "From the Desk of Washington Matthews". The Journal of American Folklore. American Folklore Society. 73 (290): 317–325. doi:10.2307/538492. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ↑ Catalogue of Oberlin College for the Year 1890-1891. Catalogue of Oberlin College. Oberlin, Ohio: The Oberlin News Free Press. 1890. p. 80. Retrieved June 9, 2009. Link mentions that she found photos of Berthold Matthews at Oberlin in Matthews' belongings, and a Berthold Matthews from Yankton, South Dakota is listed in the 1890 catalog at Oberlin. Presumably Matthews named him after the Fort where he was born.

- 1 2 Merbs, Charles F. (Autumn 2002). "Washington Matthews and the Hemenway Expedition of 1887-88". Journal of the Southwest. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. ISSN 0894-8410. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ↑ "7th Annual Meeting of the American Folk-Lore Society". XXV (725). Good Literature Publishing Company. 1896: 26.

- ↑ Powell, J.W. (1888). "Work of Doctor Washington Matthews". Sixth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Director of the Smithsonian 1884-85. Washington DC: Government Printing Office: XXXVIII–XL.

- ↑ Matthews, Washington (1898). "Ichthyphobia". The Journal of American Folk-lore. Published for the American Folk-lore Society by Houghton Mifflin: 105–112.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1872). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-19-511271-9.

- ↑ "Who's In a Name: Loeseliastrum matthewsii". Retrieved June 30, 2009.

External links

- Works by Washington Matthews at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Washington Matthews at Internet Archive

- Works by Washington Matthews at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)