Mass amateurization

Mass amateurization refers to the capabilities that new forms of media have given to non-professionals and the ways in which those non-professionals have applied those capabilities to solve problems (e.g. create and distribute content) that compete with the solutions offered by larger, professional institutions.[1] Mass amateurization is most often associated with Web 2.0 technologies. These technologies include the rise of blogs and citizen journalism, photo and video-sharing services such as Flickr and YouTube, user-generated wikis like Wikipedia, and distributed accommodation services such as Airbnb. While the social web is not the only technology responsible for the rise of mass amateurization, Clay Shirky claims Web 2.0 has allowed amateurs to undertake increasingly complex tasks resulting in accomplishments that would seem daunting within the traditional institutional model.

In addition to whole websites and applications, Web 2.0 has also birthed a variety of digital tools that facilitate organization and problem solving on a large scale. These tools include tags, trackbacks, and hashtags. These new forms of media became widely available during the first decade of the 21st century due in part to the fall of transactional costs of creating and distributing media.[2] Mass amateurization is a social, cumulative and collaborative activity, wherein ideas will flow back up the pipeline from consumers and they will share them among themselves.[3]

There is no institutional hierarchy in mass amateurization. There is only an informal group of collaborators working to solve a problem. Due to mass amateurization, amateurs are able to collaborate without the interference from the inherent obstacles associated with institutions. These obstacles include the costs that an institution incurs while educating, training, directing, coaching, advising, and organizing its members.[1][2][4][5]

Background

Mass amateurization was first popularized by Clay Shirky in his 2008 book, Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations. Shirky notes that blogging, video-sharing and photo-sharing websites allow anyone to publish an article or photo without the need of being vetted by professionals such as news or photo editors. Mass amateurization is changing the definition of words like journalist and photographer to include non-professionals outside of the institutional realm. Furthermore, mass amateurization is changing the way news and other content is diffused and consumed by the public through various media outlets.[1] George Lazaroui explains that mass amateurization "is a result of the radical spread of expressive capabilities," due to "an explosion of Internet tools designed to make media authoring easier" during the early 21st Century.[2]

- "Our social tools remove older obstacles to public expression, and thus remove the bottlenecks that characterized mass media. The result is the mass amateurization of efforts previously reserved for media professionals." -Clay Shirky

Circumventing institutional training

Mass amateurization can also be described as a technological and cultural phenomenon whereby ordinary people access information-disseminating technologies that were historically only available to professionals. Specifically, Shirky cites collaborative projects such as Wikipedia and Linux.[1] Here, the term "amateur", is not defined by the absence of money or skill, since the modern amateur can acquire consumer, prosumer, and professional-level technologies with increasing ease. Instead, an amateur can be described as a producer without traditional credentials or institutional training.[6]

Emerging grassroots creativity

Media scholar Henry Jenkins writes in Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, that "the story of American Arts in the twenty-first century might be told in terms of the public reemergence of grassroots creativity as everyday people take advantage of new technologies that enable them to archive, annotate, appropriate, and recirculate media content."[7] This grassroots creativity is a form of mass amateurization because everyday people are creating interesting content that might not have been created by film or television institutions. In Jenkin's book one of the examples of is fan films, which are made possible thanks to the low transactional costs associated with making modern films. On the whole, individual amateurs suffer fewer costs when solving problems than institutions. Institutions have to buy land, construct buildings, recruit members or employees, and procure technologies so that their members can solve problems. Conversely, amateurs do not require those steps because they presumably already have their own house and computer at their disposal. They simply do not have to put as much effort into solving a problem as an institution would and that allows them to be competitive.[5]

Developing skills as a leisure

In his 1992 book Amateurs, Professionals, and Serious Leisure, Robert A. Stebbins refers to the phenomenon of mass amateurization as "serious leisure." [4] Stebbins views mass amateurization as a way to replace typical mundane employment as well as allow a person to increase their personal skills and value. He defines serious leisure as "the systematic pursuit of an amateur, hobbyist, or volunteer activity that is sufficiently substantial and interesting for the participant to find a career there in the acquisition and expression of its specials skills and knowledge."[4] This amateurization often occurs within "free time, spare time, uncommitted time, (and) discretionary time."[4] Stebbins notes that compared to their 'publics,' both amateurs and professionals are the more capable groups. Furthermore, "the good amateurs are better than the mediocre professionals."[4] This is how amateurs are able to threaten professional institutions. Institutions only have the resources to gather a certain number of professionals. Alternatively, the amateurs of the world do not need to put forth any resources to gather themselves. That is, they already exist within the world, all that is left to do is work. And since the world is so large, amateurs outnumber professionals in many fields. For instance, even if there are only 1000,000 amateurs in a field, that law of averages indicates that enough of them will be those "good amateurs" and therefore be able to compete with the limited number of "mediocre professionals" that make up most of the institutional space.[4]

History

The concept of mass amateurization is not limited to Web 2.0 or other digital technologies. The phenomenon has occurred throughout history as certain technologies have become more readily available to the public thanks, in part, to low transactional costs.

Photography

As the costs of camera technology fell, more and more amateurs gained accessibility to photography technology. Now average people could shoot, develop and edit their own photographs in their own time. Previously anyone taking photographs would have to have relied on the institutional model.

Videography/film-making

A fall in the cost of consumer video recording technology in the early 1980s meant that amateurs were now free to make their own films at home. In Convergence Culture, Henry Jenkins examines how a fall in the cost of video recording technology led to the rise of amateur films, particularly fan film. Fan films mentioned by Jenkins include Kid Wars, The Jedi Who Loved Me, and Boba Fett: Bounty Trail. While discussing the Star Wars prequels filmmaker George Lucas once referenced mass amateurization by stating "Some of the special effects that we redid for Star Wars were done on a Macintosh, on a laptop, in a couple of hours.... I could have very easily shot the Young Indy TV series on Hi-8....So you can get a Hi-8 camera for a few thousand bucks, more for the software and the computer for less than $10,000 you have a movie studio."[7]

Citizens band radio

The fall in costs of transmitter technology led to the spread of citizens band radio (CB radio for short). CB radio allowed amateurs to have control over certain frequencies in the radio spectrum that was previously reserved for use by the government or various broadcast corporations. Amateurs could tinker with equipment and use the frequencies for their own purposes.

Meteorology

As meteorological equipment and texts became more accessible, amateurs were able to scientifically monitor the weather by taking measurements with barometers and observing the skies.

Astronomy

Astronomy can now be performed by amateurs thanks to the availability of binoculars and telescopes. Many amateur astronomers make a contribution to astronomy by monitoring variable stars, tracking asteroids and discovering transient objects, such as comets. In fact, amateur astronomer Thomas Bopp is co-credited with discovering Comet Halle-Bopp.

Mass amateurization and the Internet

Internet technologies foster disintermediation and new forms of collaboration within the digital space.

Wikis

Wikis allow for the mass amateurization of encyclopedic authorship. They typically have a set of rules and guidelines that allow amateurs to navigate and contribute to a collection of knowledge. All that is typically necessary to edit a wiki is an email address. All that is required to remain a member of a wiki editor community is to obey the rules and guidelines of said wiki. This manifestation of mass amateurization allows amateur researchers and authors to directly compete with institutionally established encyclopedias and other collections such as Encyclopædia Britannica.

Examples of wikis include:

Photo-sharing

Flickr allows amateur photographers to publish and share photographs at no cost. Flickr also allows users access to a community of photographers that might have previously been only accessible to those paying for photography classes at an institution. In this space, users can receive criticism and guidance from other photographers. In his 2005 TED talk, Clay Shirky illustrated how amateurs have used tags on Flickr to solve the problem of organizing photographs. His example problem is that he wants to find pictures of the Coney Island Mermaid Parade. In an institutional model, a photographer would be paid to go to the parade, take pictures, edit those pictures, and return those pictures to Shirky. But with the powers of mass amateurization and tags, Shirky is able to quickly assemble dozens of photos of the Mermaid Parade without putting forth much effort or spending any money.[8]

See List of photo sharing websites for more examples like Flickr.

YouTube

YouTube represents the epitome of the mass amateurization of video. Amateur filmmakers and hundreds of other hobbyists can share videos with the world at no cost. The ability to publish videos and films was formerly reserved for those professionals who could afford to own and operate television stations and film studios.[7]

Airbnb

Airbnb has allowed for the mass amateurization of the hospitality industry. Users of the site can find places to stay during their travels without having to patronize professional institutions.

See also CouchSurfing.

Citizen media

Citizen media refers to forms of content produced by private citizens who are otherwise not professional journalists and/or not associated with formal institutions.

Mass amateurization is considered to be "the principal threat"[2] to all newspapers, as opposed to other, institutionalized newspapers. Other media industries in general have suffered from the fall of transactional costs and the advent of "communication tools that are flexible enough to match our social capabilities."[2] In particular, the mass amateurization has led to an increase in international news reporting that would not be financially justifiable in the professional model of publishing.[2][8] Lazaroui points out that "Many people in the newspaper business missed the significance of the internet (the only threats they tended to take seriously were from other professional media outlets). The media industries have suffered from the recent collapse in communications costs. The future presented by the internet is the mass amateurization of publishing."[2]

In some instances, there has been an overlap between professionals and amateurs where professional organizations will utilize media produced by amateurs. One example of this is when a professional news outlet is sent firsthand footage of a "newsworthy" event that would otherwise be unavailable.[3]

However, other crossovers are not always so useful. In 2005, the Los Angeles Times attempted to offer its online readers access to its "Wikitorial", which allowed users to edit and contribute the website's editorial page. This led to widespread vandalism throughout the article and eventually its removal.[9]

Examples of citizen media in the Web 2.0 space include Reddit and any blog wherein the author conducts original investigative journalism.

In March 2014, blogger and novelist James Wesley Rawles launched a web site that provides free press credentials for citizen journalists called the Constitution First Amendment Press Association (CFAPA).[10][11][12] According to David Sheets of the Society for Professional Journalists, Rawles keeps no records on who gets these credentials.[10]

Social media

In modern news, social media has become a major source of amateur reporting. The Arab Spring is believed to have been aided by citizen journalism that was reported using and disseminated by Facebook and Twitter.

The Top 15 Most Popular Social Media Sites[13] range from 15 million users to 900 million users, and as their user base grows stronger, amateur reporting's base expands as well.

Editing and publishing

Sites like Writer's University have led to the mass amateurization of editing while hundreds of fanfiction sites have led to the amateurization of publishing. Amateur writing sites encourage "beta readers" to work with amateur authors in order to guide them and help them to improve their writing.[7] Sites like these completely circumvent the need for formal editorial institutions. The advent of E-book readers has further allowed amateur authors to distribute their work.

Institutions vs. collaboration

One of the results of mass amateurization is that it often results in amateurs being able to compete with professional institutions. In a 2005 TED Talk, Shirky claimed that amateurs in a state of collaboration have great advantages over those who are members of an institution. [14]

Concept

Institutions are created as answers to problems and they rely on a professional class of people to do work. These professionals are brought together, often to a single location and compensated to collaborate on problems. Merely assembling these professionals comes is costly. The institution often spends a great deal of time, effort and money seeking, gathering, educating, training, housing, advising, and organizing these professionals. In essence, a great deal of time and effort is spent to form a "monetary and organizational relationship" that will lead to the solution of a given problem.[4]

Inevitably some people with the right professional skills will be missed by the institution because they could never hope to exert the effort and acquire the resources necessary to gather every professional on the planet. For example, photographers who are hired, paid, and gathered under the supervision of a larger, professional institution will be able to take a lot of good pictures. However, not all of the professional photographers in the world can be hired and therefore there is a limited amount of photography work that the institution can accomplish.[14]

Institutions are also profit-driven. Specific tasks must be completed by certain deadlines or the institution will lose money. If a car company were to allow its workers to work on only what they wanted when they wanted, they would go out of business. In order to function, institutions must remain commercially viable.[1] This is not the case with non-commercial collaborative efforts, which involves a less structured process. Within institutions, "professionals are often too busy polishing their technique...to find time to read about the history of their endeavor or about the forms, styles, periods, or persons beyond their immediate work."[4] In contrast, amateurs have time to develop their work whenever and wherever they want. They can explore new areas of their work and have complete autonomy to carry out their work however they want. This flexibility is a large part of why amateurs can compete with and often surpass institutions.

The effectiveness of mass amateurization is made possible because "digital culture fosters community while at the same time can be fueled by isolation." That is to say that digital culture and the Web 2.0 digital space cut down on costs typically associated with operating an institution. Amateurs in this space do not need to physically meet in order to collaborate and solve problems.[2]

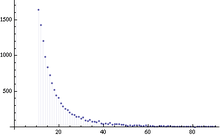

Collaborators and power law

Amateurs, or collaborators, are not formally organized, they do not carry titles relating to their collaboration, and collaborators can have any level of skill. In Clay Shirky's example, users on Flickr fall into the definition of collaborators and they, without any institutional guidance, figured out how to solve the problem of organizing photographs.[14] To further illustrate his point he references what is commonly known as the 80/20 rule; also known as power law distribution. By harvesting the efforts of multiple amateurs, one can end up with a more valuable result than if one had relied on the traditional institutional model.[14] This distribution dictates that 20% of a group will produce 80% of the content. With power law, the most active contributor is far more active than the second most active, who is far more active than the rest. Here, most producers only contribute relatively minor additions. In this distribution, the mean, median, and mode are typically very different in a power law curve.[1] Due to this contrast in production among contributors, traditional hierarchy is replaced with a heterarchical format wherein distinct roles are blurred.[1][15]

According to Leadbeater, "committed amateurs" can devise effective solutions so long as they get access to the knowledge and resources they need.[3] These resources are now more readily available today due to low transactional costs and recent technological innovations in media creation.[2]

Opposition

Within Web 2.0, amateurs have now become a legitimate threat to powerful corporations and institutions. There is an understanding that "institutions will try to preserve the problem for which they are the solution." This is referred to as the "Shirky principle."[16] It can be inferred that institutions will oppose any mass amateurization that threatens their way of business.

Criticisms

Availability

While mass amateurization enables the multiplication and overabundance of content, the societal capacity to process and digest this content is all but certain.[2] Lazaroui notes that "material published in a content-rich environment is destined to remain obscure"[2] and therefore the benefits of mass amateurization are not as accessible to society as they could be.

Originality

Lazaroui makes the case that most amateurs are not doing any original research. Instead they rely on professional institutions to report the news and then simply "amplify" the story. He also points out that formal news-gathering institutions have grown aware of the value of original reporting that does happen and are harnessing that power for their own use.[2] An example of this would be CNN's iReport. He charges that amateur reporters "need to focus on making this content accessible and interesting to new audiences," rather than aiding professional institutions in their news monopoly.[2]

Reliability

In 2004, Encyclopedia Britannica editor Robert McHenry referred to Wikipedia, which allows anyone to edit its articles and refers to itself as a "faith-based encyclopedia". Citing an article on Alexander Hamilton, McHenry argues that however reliable an article may be, it is always open to be altered by someone who is uninformed.[17]

Quality

Mass amateurization is a multi-faceted phenomenon that works under different conditions than professional organizations. In most cases, those who contribute content do so voluntarily and without monetary compensation. At the same time, amateur productions are often not high quality compared to their professional counterparts. This can be seen by comparing an amateur blog on blogspot to one created by a staff writer for the New York Times. This is similar to the criticism by McHenry when comparing Wikipedia to Britannica.[17] While amateur media is often faster and more public, professional media is seen as higher quality.[6] However, while amateur content may not always favorably compare to its professionally produced counterpart, both play a major role in modern media.[18]

Henry Jenkins admits that "most of what the amateurs create is gosh-awful bad," but he is quick to admit that "a thriving culture needs spaces where people can do bad art, get feedback, and get better.[7]

Copyright infringement

The mass amateurization of film making has led to multiple cases of copyright infringement. Henry Jenkins uses the infringement upon Lucasfilm properties as an example.[7]

Exploitation of amateurs

Institutions have been known to harness the power of mass amateurization for their own profit thereby turning the efforts of everyday people into free labor. For example, news corporations who ask ordinary citizens to report news for them (e.g. CNN's iReport) and websites that publish amateur-generated content in place of original, professional content creation (e.g. CNN's article about the Funniest Tweets of the Final Presidential Debate[19]).

See also

- Power Law

- Produsage

- Commons

- Clay Shirky

- Citizen Journalism

- Barefoot College

- Amateur professionalism

- Crowdsourcing

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Shirky, Clay (2008). Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organization without Organizations.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Lazaroui (2010). "The Creation and Communication of a Shared Social Reality". Economics, Management, and Financial Markets. 5 (3): 257–265.

- 1 2 3 Leadbeater, Charles (2008). We-Think.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Stebbins, Robert (1992). Amaterus, Professionals, and Serious Leisure. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-0901-1.

- 1 2 Shirky, Clay. "The Collapse of Complex Societies". Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- 1 2 Castillo, Jose (April 12, 2012). "Professional vs. Amateur Media". EContent. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jenkins, Henry (2006). 'Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press.

- 1 2 Shirky, Clay (December 2011). "Institutions Confidence and the News Crisis". Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ↑ Glaister, Dan (21 June 2005). "LA Times 'wikitorial' gives editors red faces". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- 1 2 Sheets, David (23 May 2014). "Survivalist starts issuing his own press passes". The SPJ Blog. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ http://www.CFAPA.org

- ↑ "Constitution First Amendment Press Association (CFAPA) Free Press Credentials (Free Press Pass) - An Independent Press Association". CFAPA.org.

- ↑ "Top 15 Most Popular Social Networking Sites". eBizMBA.com. April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Shirky, Clay (2005). Clay Shirky: Institutions vs. collaboration (Video). TEDTalksDirector. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ↑ Endfield, Georgina H.; Morris, Carol (February 2012). "Exploring the role of the amateur in the production and circulation of meteorological knowledge". Climate Change. 2012 (113): 77.

- ↑ Kelly, Kevin. "The Shirky Principle". The Technium. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- 1 2 McHenry, Robert (15 November 2004). "The Faith-Based Encyclopedia". TCS Daily. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ↑ "The Experts vs. the Amateurs: A Tug of War over the Future of Media". University of Pennsylvania. March 19, 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ Kelly, Heather (23 October 2012). "Funniest tweets of the final presidential debate". CNN.com. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

Bibliography

- Endfield, Georgina H.; Morris, Carol (February 2012). "Exploring the role of the amateur in the production and circulation of meteorological knowledge". Climate Change 2012 (113): 77.

- Glaister, Dan (21 June 20015). "LA Times 'wikitorial' gives editors red faces publisher = The Guardian". Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- Lazaroui (2010). "The Creation and Communication of a Shared Social Reality". Economics, Management, and Financial Markets 5 (3): 257-265.

- Leadbeater, Charles. We-think. London: Profile, 2008. We Think. Web. 27 Feb. 2013.

- McHenry, Robert (15 November 2004). "The Faith-Based Encyclopedia". TCS Daily. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- Shirky, Clay (2005). Clay Shirky: Institutions vs. collaboration (Video). TEDTalksDirector. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- Shirky, Clay (2008) "Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations"

- Shirky, Clay (December 2011). "Institutions Confidence and the News Crisis". Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- Shirky, Clay (April 2010). "The Collapse of Complex Business Models". Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- Shirky, Clay (June 2009). Clay Shirky: How Social Media Can Make History (Video). TEDTalksDirector. Retrieved April 1, 2013

- Stebbins, Robert (1992) "Amateurs, Professionals, and Serious Leisure"

- Wolske, Martin, Eric Johnson, and Paul Adams. "Citizen professional toolkits: empowering communities through mass amateurization." (2010).