Masonic ritual and symbolism

Masonic ritual refers to the scripted words and actions that are spoken or performed during the degree work in a Masonic Lodge. Masonic symbolism is that which is used to illustrate the principles which Freemasonry espouses. Masonic ritual has appeared in a number of contexts within literature including in The Man Who Would Be King, by Rudyard Kipling, and War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy.

The purpose of Masonic ritual

Freemasonry is described in its own ritual as a Beautiful or Peculiar system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols.[1] The symbolism of freemasonry is found throughout the Masonic Lodge, and contains many of the working tools of a medieval or renaissance stonemason. The whole system is transmitted to initiates through the medium of Masonic ritual, which consists of lectures and allegorical plays.[2]

Common to all of Freemasonry is the three grade system of craft or blue lodge freemasonry, whose allegory is centred on the building of the Temple of Solomon, and the story of the chief architect, Hiram Abiff.[3] Further degrees have different underlying allegories, often linked to the transmission of the story of Hiram. Participation in these is optional, and usually entails joining a separate Masonic body. The type and availability of the Higher Degrees also depends on the Masonic Jurisdiction of the Craft Lodge that first initiated the mason.[4]

Lack of standardisation

Freemasons conduct their degree work, often from memory, following a preset script and ritualised format. There is a variety of different Masonic rites for Craft Freemasonry. Each Masonic jurisdiction is free to standardize (or not standardize) its own ritual. However, there are similarities that exist among jurisdictions. For example, all Masonic rituals for the first three degrees makes use of the architectural symbolism of the tools of the medieval operative stonemason. Freemasons, as speculative masons (meaning philosophical rather than actual building), use this symbolism to teach moral and ethical lessons, such as the four cardinal virtues of Fortitude, Prudence, Temperance, and Justice, and the principles of "Brotherly Love, Relief (or Morality), and Truth" (commonly found in English language rituals), or "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" (commonly found in French rituals).

Symbols in ritual

In most jurisdictions a Bible, Quran, Talmud, Vedas or other appropriate sacred text (known in some rituals as the Volume of the Sacred Law) will always be displayed while the Lodge is open (in some French Lodges, the Masonic Constitutions are used instead). In Lodges with a membership of mixed religions it is common to find more than one sacred text displayed. A candidate will be given his choice of religious text for his Obligation, according to his beliefs. UGLE alludes to similarities to legal practice in the UK, and to a common source with other oath taking processes.[5][6]

In keeping with the geometrical and architectural theme of Freemasonry, the Supreme Being is referred to in Masonic ritual by the titles of the Great Architect of the Universe, Grand Geometrician or similar, to make clear that the reference is generic, and not tied to a particular religion's conception of God.[7]

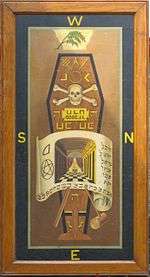

Some lodges make use of tracing boards: painted or printed illustrations depicting the various symbolic emblems of Freemasonry. They can be used as teaching aids during the lectures that follow each of the three degrees, when an experienced member explains the various concepts of Freemasonry to new members.

Solomon's Temple is a central symbol of Freemasonry which holds that the first three Grand Masters were King Solomon, King Hiram I of Tyre, and Hiram Abiff—the craftsman/architect who built the temple. Masonic initiation rites include the reenactment of a scene set on the Temple Mount while it was under construction. Every Masonic Lodge, therefore, is symbolically the Temple for the duration of the degree and possesses ritual objects representing the architecture of the Temple. These may either be built into the hall or be portable. Among the most prominent are replicas of the pillars Boaz and Jachin through which every initiate has to pass.[8]

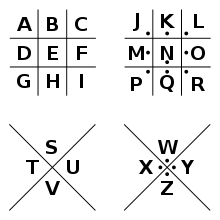

Historically, Freemasons used various signs (hand gestures), grips or "tokens" (handshakes), and passwords to identify legitimate Masonic visitors from non-Masons who might wish to gain admission to meetings. These signs, grips, and passwords have been exposed multiple times; today Freemasons use dues cards and other forms of written identification.[9]

Overlap with Mormon symbolism

Mormon temple worship shares a commonality of symbols, signs, vocabulary and clothing with Freemasonry, including robes, aprons, handshakes, ritualistic raising of the arms, etc.[10] However, the meanings of each are different for the Freemasons and the Mormons (members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).

Speaking in 1877 at the St. George Temple, Brigham Young related LDS temple worship to the story of Hiram Abiff and Solomon's Temple, though he believed the ceremony had not been practiced in its fullness.[11][12]

Perceived secrecy of Masonic ritual

Some Masonic ritual involves “bloody oaths” by which the initiate swears to keep secret the key parts of the ceremony for a new degree, on pain of death.

The Morgan Affair and its aftermath

The mysterious disappearance of William Morgan in 1826 was said to be due to his threat to publish a book detailing the secret rituals of Freemasonry.

An attempt was made to burn down the publishing house, and separately, Morgan was arrested on charges of petty larceny. He was seized and taken to Fort Niagara, after which he disappeared.[13] The suspicion behind this led to the creation of the Anti-Masonic Party, which enjoyed brief popularity but rapidly became defunct after they fielded a Freemason as their presidential candidate in 1832.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ University of Bradford, Web of Hiram First Degree Lecture, pub. Lewis, London, 1801

- ↑ UGLE website What is Freemasonry, retrieved 12th Jan 2013

- ↑ Pietre-Stones Kent Henderson, The Legend of Hiram Abif, retrieved 12th Jan 2013

- ↑ Fred L. Pick, The Pocket History of Freemasonry, pp. 268-280.

- ↑ "What promises do Freemasons take?". United Grand Lodge of England. 2002. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ Jacob, Margaret C. (2005). The origins of freemasonry: facts & fictions. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812239010. OCLC 61478025.

- ↑ King, Edward L. (2007). "GAOTU". Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- ↑ James Stevens Curl, The Art and Architecture of Freemasonry, Overlook Press, New York, 1991, 56-62.

- ↑ Hodapp, Christopher. Freemasons for Dummies. Indianapolis: Wiley, 2005. pp. 18, 25.

- ↑ Goodwin (1920, pp. 54–59).

- ↑ "It is true that Solomon built a temple for the purpose of giving endowments, but from what we can learn of the history of that time they gave very few if any endowments, and one of the high priests [Hiram Abiff] was murdered by wicked and corrupt men, who had already begun to apostatize, because he would not reveal those things appertaining to the priesthood that were forbidden him to reveal until he came to the proper place." Brigham Young (January 1, 1877), "Remarks by President Brigham Young". Journal of Discourses Vol. 18, page 303. Also quoted in "Temple and Salvation for the Dead", Discourses of Brigham Young, compiled by John A. Widtsoe, Deseret Book Company, 1977

- ↑ Michael W. Homer (2014). "Utah Freemasonry: Solomon Built a Temple for Giving Endowments". Joseph's Temples: The Dynamic Relationship Between Freemasonry and Mormonism (ebook). The University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-1-60781-346-0.

- ↑ Peck, William F. (1908). History of Rochester and Monroe county, New York. The Pioneer publishing company. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- ↑ Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon “The Morgan Affair aftermath”, retrieved 21 September 2013