Maryland Senate

| Maryland State Senate | |

|---|---|

| Maryland General Assembly | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

Term limits | None |

| History | |

New session started | January 12, 2011 |

| Leadership | |

President of the Senate | |

President pro Tempore | |

Majority Leader | |

Minority Leader | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 47 |

| |

Political groups |

Governing party Opposition party |

Length of term | 4 years |

| Authority | Article III, Section 2, Maryland Constitution |

| Salary | $43,500/year + per diem |

| Elections | |

Last election |

November 4, 2014 (47) |

Next election |

November 1, 2018 (47) |

| Redistricting | Legislative Control |

| Meeting place | |

| |

|

State Senate Chamber Maryland State House Annapolis, MD | |

| Website | |

| Maryland State Senate | |

The Maryland Senate, sometimes referred to as the Maryland State Senate, is the upper house of the General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland. Composed of 47 senators elected from an equal number of constituent single-member districts, the Senate is responsible, along with the Maryland House of Delegates, for passage of laws in Maryland, and for confirming executive appointments made by the Governor of Maryland.

It evolved from the upper house of the colonial assembly created in 1650 when Maryland was a proprietary colony controlled by Cecilius Calvert. It consisted of the Governor and members of the Governor's appointed council. With slight variation, the body to meet in that form until 1776, when Maryland, now a state independent of British rule, passed a new constitution that created an electoral college to appoint members of the Senate. This electoral college was abolished in 1838 and members began to be directly elected from each county and Baltimore City. In 1972, because of a Supreme Court decision, the number of districts was increased to 47, and the districts were balanced by population rather than being geographically determined.

To serve in the Maryland Senate, a person must be a citizen of Maryland 25 years of age or older. Elections for the 47 Senate seats are held every four years coincident with the federal election in which the President of the United States is not elected. Vacancies are filled through appointment by the Governor. The Senate meets for three months every year; the rest of the year the work of the Senate is light and most members hold another job during this time. It has been controlled by Democrats for a number of years. In the 2006 election, more than two-thirds of the Senate seats were won by Democrats.

Senators elect a President to serve as presiding officer of the legislative body, as well as a President Pro Tempore. The President appoints chairs and membership of six standing committees, four legislative committees as well as the Executive Nominations and Rules Committees. When compared to other state legislatures in the United States, the Maryland Senate has one of the strongest presiding officers and some of the strongest committee chairs. Senators are also organized into caucuses, including party- and demographically-based caucuses. They are assisted in their work by paid staff of the non-partisan Department of Legislative Services and by partisan office staff.

History

The origins of the Maryland Senate lie in the creation of an assembly during the early days of the Maryland colony. This assembly first met in 1637, making it the longest continuously operating legislative body in the United States.[1] Originally, the assembly was unicameral, but in 1650, the Governor and his appointed council began serving as the upper house of a now bicameral legislature. These appointees had close political and economic ties to the proprietors of the Maryland colony, Cecilius Calvert and his descendants. Thus, the upper house in colonial times often disagreed with the lower house, which was elected, tended to be more populist, and pushed for greater legislative power in the colony.[2]

The upper house was briefly abolished during the English Civil War, as Puritan governors attempted to consolidate control and prevent the return of any proprietary influence. It was again abolished by Governor Josias Fendall in 1660, who sought to create a colonial government based on an elected unicameral legislature like that of the Virginia colony. The position of Governor was removed from the legislature in 1675, but for the following century, its function and powers largely remained the same.[2]

In 1776, following the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, Maryland threw off proprietary control and established a new constitution. Under this new constitution, the upper house of the General Assembly first became known as the Maryland Senate. The new body consisted of fifteen Senators appointed to five-year terms by an electoral college. The college, made up of two electors from each county and one each from the cities of Baltimore and Annapolis, was limited in its selections only by the stipulation that nine Senators need be from the western shore and six from the eastern shore.[2]

The first election under the 1776 constitution took place in 1781, and the system would not change again until 1838. In the interim, a number of problems had cropped up in the appointment process, and the 1838 election saw the passage of a number of constitutional amendments that fundamentally changed how Senators were chosen. The electoral college was abolished, terms were lengthened to six years with rotating elections such that a third of the senate would be elected every two years, and a single Senator was chosen by direct election from each county and the City of Baltimore. The Senate no longer acted as the Governor's Council, although they would continue to confirm the Governor's appointments. Constitutional changes altered this new system slightly in 1851, when terms were shortened to four years, and 1864, when Baltimore City was given three Senate districts rather than one, but substantial change to the structure of the Senate did not come again until 1964.[2]

In 1964, the Supreme Court ruled in Reynolds v. Sims that state legislative seats must be apportioned on the principle of one man, one vote. A number of state legislatures, including Maryland, had systems based on geography rather than population, and the court rules that this violated the 14th Amendment. Disproportionate population growth across Maryland since 1838 meant that the principle of one seat per county gave the voters of some counties, such as those on the eastern shore, disproportionate representation. Other counties, especially those in suburban areas, were underrepresented.[2]

A special session of the legislature in 1965 changed the Senate to represent 16 districts and reapportioned the seats, again by county, but did so in such a way as to make the representation more proportional to population than it had been. Thus, the eastern shore, which had previously elected nine Senators, elected only four after 1965. This was done to preserve the ideal of having whole counties represented by a single Senator, rather than breaking counties up into multiple districts. A constitutional amendment in 1972 expanded the Senate to 47 members, elected from districts proportional to the population. These districts are reapportioned every ten years based on the United States Census to ensure they remain proportional.[2]

Powers and legislative process

The Maryland Senate, as the upper house of the bicameral Maryland General Assembly, shares with the Maryland House of Delegates the responsibility for making laws in the state of Maryland. Bills are often developed in the period between sessions of the General Assembly by the Senate's standing committees or by individual Senators. They are then submitted by Senators to the Maryland Department of Legislative Services for drafting of legislative language. Between 2000 and 2005, an average of 907 bills were introduced in the Senate annually during the three-month legislative session. The bill is submitted, and receives the first of three constitutionally mandated readings on the floor of the Senate, before being assigned to a committee.[3] The decision about whether legislation passes is often made in the committees. Committees can hold legislation and prevent it from reaching the Senate floor. The recommendations of committees on bills carry tremendous weight; it is rare for the Senate as a whole to approve legislation that has received a negative committee report.[1] Once a committee has weighed in on a piece of legislation, the bill returns to the floor for second hearing, called the "consideration of committee" report, and a third hearing, which happens just before the floor vote on it.[3]

Once passed by the Senate, a bill is sent to the House of Delegates for consideration. If the House also approves the bill without amendment, it is sent to the Governor. If there is amendment, however, the Senate may either reconsider the bill with amendments or ask for the establishment of a conference committee to work out differences in the versions of the bill passed by each chamber. Once a piece of legislation approved by both houses is forwarded to the Governor, it may either be signed or vetoed. If it is signed, it takes effect on the effective date of the legislation, usually October 1 of that year. If it is vetoed, both the Senate and the House of Delegates must vote by a three-fifths majority to overturn the veto. They may not, however, overturn a veto in the first year of a new term, since the bill would have been passed during the previous session. Additionally, joint resolutions and the budget bill may not be vetoed, although the General Assembly is constitutionally limited in the extent to which it may influence the latter; it may only decrease the Governor's budget proposal, not increase it.[3]

Unlike the House of Delegates, the Senate has the sole responsibility in the state's legislative branch for confirming gubernatorial appointees to positions that require confirmation. After the Governor forwards his nomination to the Senate, the Executive Nominations Committee reviews the nominee and makes a recommendation for confirmation or rejection to the Senate as a whole.[4] Only one gubernatorial nominee in recent history has been rejected; Lynn Buhl, nominated as Maryland Secretary of the Environment by Governor Robert Ehrlich, was rejected over concerns about her qualifications.[5] The Senate also has sole responsibility for trying any persons that have been impeached by the House of Delegates. They must be sworn in before such a trial takes place, and a two-thirds majority is required for conviction of the impeached person.[6]

Composition

| Affiliation | Party (Shading indicates majority caucus) |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Republican | Vacant | ||

| 2007–2010 Session | 33 | 14 | 0 | 47 |

| Previous Legislature (2011–2014) | 35 | 12 | 0 | 47 |

| Begin (2015–2018)[7] | 33 | 14 | 0 | 47 |

| Latest voting share | 70.2% | 29.8% | ||

Organization

Maryland's Senate consists of Senators elected from 47 Senate districts. While each Senator has the power to introduce and vote on bills and make motions on the floor, various committees, caucuses, and leadership positions help to organize the work of the Senate. Senators elect a President of the Senate, who serves as the presiding officer of the chamber. They also elect a President Pro Tempore, who presides over the chamber when the President is absent.[8] The President of the Maryland Senate has significant influence over legislation that passes through the body through both formal means, such as his ability to appoint committee chairs and leaders of the majority party, and informal means that are less easily defined.[1][4][9] These powers place the President of the Maryland Senate among the strongest state legislature presiding officers in the country.[1]

Once legislation is introduced, it is passed to one of the standing committees of the Senate. There are six such committees.[4] As a whole, the Maryland General Assembly has fewer standing committees than any other state legislature in the United States. Each committee has between 10 and 15 members.[1] Four of the standing committees deal primarily with legislation; the Budget and Taxation Committee, the Education, Health, and Environmental Affairs Committee, the Finance Committee, and the Judicial Proceedings Committee.[4] The Chairs of these legislative committees have the power to determine whether their committees will hear a bill, and they therefore have significant influence over legislation.[1] The Executive Nominations Committee manages the Senate's responsibility to confirm gubernatorial appointments and makes recommendations of approval and disapproval to the body as a whole. Lastly, the Rules Committee sets the rules and procedures of the body. It also has the power to review legislation that has been introduced by a member of the Senate after the deadline for submission, and decide whether to refer it to a standing committee or let it die.[4] Along with serving on the Senate committees, members of the Senate also serve on a number of joint committees with members of the House of Delegates.[8]

While the committees are established by formal Senate rules, there are a number of caucuses that exercise significant influence over the legislative process. The most powerful of these are the Democratic Caucus and the Republican Caucus, each of which has a leader and a whip, referred to as a majority and minority leader and whip.[8] As Democrats currently control a majority of seats in the Senate, their leader is referred to as the Majority Leader, and their caucus is able to influence legislation to a greater extent than the Republican caucus. The Majority Leader and Minority leader are responsible for managing their party's participation in debate on the floor. Party caucuses also raise and distribute campaign money to assist their candidates.[1] The Legislative Black Caucus of Maryland and Women Legislators of Maryland, caucuses of African-American and female Senators respectively, also play prominent roles in the Senate.[10]

Professional services for members of the Senate and the House of Delegates are provided by the Department of Legislative Services, which is non-partisan. Individual members are also assisted by partisan staff members, and those in leadership positions have additional partisan staff.[1] These staff members help to manage the offices of the Senators in the Miller Senate Office Building. Each Senator has one year-round administrative assistant, as well as a secretary who assists them during the legislative session. There is also an allowance given to help pay for district offices.[11]

Membership

Qualifications

To be eligible to run for the Maryland Senate, a person must be a citizen and be at least 25 years old. They must also have lived in the state for at least one year, and must have lived in the district in which they are to run for at least six months, assuming the district has existed with its current boundaries for at least that long. No elected or appointed official of the United States government, including the military, may serve in the Senate, excluding those serving in the military reserves and National Guard. Similarly, no employees of the state government may serve, except for law enforcement officers, firefighters, and rescue workers.[6]

Elections and vacancies

Members of the Maryland Senate are elected every four years, in off-year elections in the middle of terms for Presidents of the United States.[6] Party nominations are determined by primary elections.[1] The general election for Senate seats and all other state and federal elections in the normal cycle is held on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Should a Senate seat become vacant in the middle of a term, because of death, illness, incapacitation, disqualification, resignation, or expulsion of a member of the Senate, that seat is filled by appointment. The Central Committee of the previous Senator's party in the county or counties in which the Senate district lies makes a recommendation to the Governor on whom to appoint to the seat. Within fifteen days of the Central Committee's recommendation being selected, the Governor must appoint that person to the vacant seat.[6]

The 47 districts from which Senators are elected are apportioned every ten years on the basis of population. Maryland's constitution explicitly defines the process for the drawing of these districts, requiring that the Governor make a recommendation of a new electoral map and submit it for legislative approval. As of 2005, there were approximately 112,000 people in each district. Each Senate district also elects three Delegates, and incumbent Senators and Delegates will often run jointly as members of incumbent slates in their districts. It is rare, however, for an incumbent to be challenged.[1]

Salaries and benefits

As of the 2006–2010 term, most of Maryland's Senators and Delegates receive $43,500 in annual pay while presiding officers earn $56,500.[11] This pay, relatively low for a state legislator, reflects the part-time nature of the body, which only meets three months out of the year. Most members of the Senate hold additional jobs during the remainder of the year.[1] Senators can also seek reimbursement for expenses related to meals and lodging during the legislative session, and for certain travel expenses related to their duties at any point during the year. They also have access to benefits received by state employees, including health and life insurance as well as retirement savings plans. Maryland has a voluntary legislator pension plan to which both Senators and Delegates have access. Besides receiving their own benefits, Senators can award up to $138,000 each year in scholarships to students of their choosing if those students meet requirements set by Senate rules.[11]

Current makeup

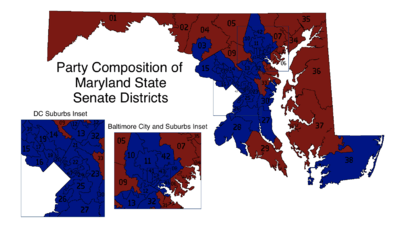

As of November 2015, a majority of seats in the Maryland Senate are held by members of the Democratic Party, with 33 Democrats and 14 Republicans, greater than a two-thirds majority.[12][13] This dominance is nothing new, as Democrats have had strong majorities in the chamber for decades. Democrats tend to control seats in the large population centers such as Baltimore City, Montgomery County, and Prince George's County, while Republicans control most seats on the Eastern Shore and in western Maryland. The chamber has also had significant numbers of women and African-Americans serve, with women averaging around 30% of the seats and African-Americans around 20%.[1]

Leadership

As of 2009, Thomas V. Mike Miller, Jr. was serving his fifth term as President of the Senate. Nathaniel J. McFadden, from the 45th district in Baltimore, is the President Pro Tempore. The Democratic caucus is led by Catherine E. Pugh, the majority leader, and Lisa A. Gladden, the majority whip. J. B. Jennings serves as minority leader.[14]

Rules and procedures

Many rules and procedures in the Maryland Senate are set by the state constitution.[6] Beyond the constitutional mandates, rules in the Senate are developed by the Rules Committee.[4] The Senate and House of Delegates both meet for ninety days following the second Wednesday in January, although these sessions may be extended for up to thirty days by majority votes in both houses, and special sessions may be called by the Governor.[1] The Senate meets in the Senate Chamber of the Maryland State House, which has both gallery seating and a door open to the State House lobby, the latter being mandated by the state constitution.[6] Seating in the Senate is by party, with the leaders of each party choosing the exact seating assignments.[1] Each Senator has offices in Annapolis, in the Miller Senate Office Building.

A typical session of the Senate begins with a call to order by the President of the Senate. After the call to order, the previous day's journal is approved, petitions are heard, and orders involving committee and leadership appointments or changes to the rules are presented. First, readings of legislation take place. Senators are then given leeway to introduce any visitors, often people observing its deliberations from the gallery above the Senate chamber. Then the Senators consider legislation. They begin with unfinished business from the previous session, then consider legislation and special orders with accompanying reports from committees. At the discretion of the presiding officer, the Senate may adjourn at any time, unless a majority of members present object to adjournment.[15]

Lobbying is common in Annapolis; there are more than 700 lobbyists registered with the state. While lobbyists may spend freely on advocacy, they are limited in gifts to legislators and in their ability to contribute to campaigns.[1] Ethics issues related to lobbyists and other matters are handled by the Joint Committee on Legislative Ethics, a twelve-member committee that includes six Senators. Members of the Senate may turn to either this committee or an ethics counsel to help them resolve questions of potential ethical conflict. Members are encouraged to avoid conflicts of interest, and are required to submit public financial disclosures to the state. In addition to employment prohibitions laid out in the state constitution, members are barred from advocating for any paying client before any part of the state government.[15]

See also

- Maryland Legislature

- Maryland House of Delegates

- Government of Maryland

- American Legislative Exchange Council members

- United States congressional delegations from Maryland#United States Senate

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Little, Thomas H. & Ogle, David B. (2006). The legislative branch of state government: people, process, and politics. ABC-CLIO. pp. 312–316. ISBN 1-85109-761-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Senate: Origins and Functions". Maryland Manual Online. Maryland State Archives. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "General Assembly — The Legislative Process: How a Bill Becomes a Law". Maryland Manual Online. Maryland State Archives. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Senate — Standing Committees". Maryland Manual Online. Maryland State Archives. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ↑ Kobell, Rona (July 21, 2008). "Lynn Buhl, EPA". Bay and Environment. Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Constitution of the State of Maryland, Article 3. Maryland State Archives.

- ↑ The Baltimore Sun (November 5, 2014). "Republicans ride GOP wave to gain General Assembly seats". Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "General Assembly: Organizational Structure". Maryland Manual Online. Maryland State Archives. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ↑ Pagnucco, Adam. "Mike Miller is Not Going Anywhere". Maryland Politics Watch. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ↑ Maryland Department of Legislative Services (2006). "Maryland Legislator's Handbook" (PDF). p. 30. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Maryland Department of Legislative Services (2006). "Maryland Legislator's Handbook" (PDF). pp. 39–41. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ↑ "Maryland Senators — Democrats". Maryland Manual Online. Maryland State Archives. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Maryland Senators — Republicans". Maryland Manual Online. Maryland State Archives. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ↑ "Membership" (PDF). Maryland General Assembly. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- 1 2 Maryland Department of Legislative Services (2006). "Maryland Legislator's Handbook" (PDF). pp. 47–51. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

External links

- Maryland General Assembly official government website

- State Senate of Maryland at Project Vote Smart

- Maryland Senate at Ballotpedia