Marie François Xavier Bichat

| Marie François Xavier Bichat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

14 November 1771 Thoirette |

| Died |

22 July 1802 (aged 30) Paris |

| Nationality | French |

| Fields |

Anatomy Physiology |

| Known for |

Histology Tissues |

| Influences | Laura Bassi |

Marie François Xavier Bichat (14 November 1771 – 22 July 1802)[1] was a French anatomist and pathologist; he is known as the father of histology. Although working without the microscope, Bichat distinguished 21 types of elementary tissues from which the organs of human body are composed.

Biography

Bichat was born at Thoirette in Jura, France. His father was Jean-Baptise Bichat, a physician who had trained at Montpellier and was Bichat's first instructor. His mother was Jeanne-Rose Bichat, his father's wife and cousin.[2] He entered the college of Nantua, and later studied at Lyon. He made rapid progress in mathematics and the physical sciences, but ultimately devoted himself to the study of anatomy and surgery under the guidance of Marc-Antoine Petit (1766–1811), chief surgeon to the Hotel-Dieu at Lyon.[3]

The revolutionary disturbances compelled him to flee from Lyon and take refuge in Paris in 1793. There he became a pupil of P. J. Desault, who was so impressed with his genius that he took him into his house and treated him as his adopted son. For two years he took active part in Desault's work, at the same time pursuing his own research in anatomy and physiology. Desault passed in 1795.[3]

At age 29 he was appointed as the chief physician to the Hotel-Dieu.[3] In 1796, he and several other colleagues formally founded the Société d'Emulation de Paris, which provided an intellectual platform for debating problems in medicine.[2] He died at age 30, fourteen days after falling down a set of stairs at Hotel-Dieu and acquiring a fever.[1] He is buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Major publications

The sudden death of Desault in 1795 was a severe blow to Bichat. His first task was to discharge the obligations he owed his benefactor, by contributing to the support of his widow and her son, and by completing the fourth volume of Desault's Journal de Chirurgie to which he added a biographical memoir of its author.[4]

His next objective was to reunite and digest in one body the surgical doctrines which Desault had published in various periodical works. Of these he composed, Œuvres chirurgicales de Desault, ou tableau de sa doctrine, et de sa pratique dens le traitement des maladies externes (1798–1799), a work in which, although he professes only to set forth the ideas of another, he develops them with the clearness of one who is a master of the subject. In 1797, he began a course of anatomical demonstrations, and his success encouraged him to extend the plan of his lectures, and boldly to announce a course of operative surgery.[4]

In 1798, he gave in addition a separate course of physiology. A dangerous attack of haemoptysis interrupted his labors for a time; but the danger was no sooner past than he plunged into new engagements with the same ardour as before. He had now scope in his physiological lectures for a fuller exposition of his original views on the animal economy, which excited much attention in the medical schools at Paris.[4]

Sketches of these doctrines were given by him in three papers contained in the Memoirs of the Société Médicale d'Émulation, which he founded in 1796, and they were afterwards more fully developed in his Traité sur les membranes (Treatise on Membranes, 1799).[5] His next publication was the Recherches physiologiques sur la vie et la mort (General Anatomy Applied to Physiology and Medicine, 1800), and it was quickly followed by his Anatomie générale (1801), the work which contains the fruits of his most profound and original researches. He began another work, under the title Anatomic descriptive (1801–1803), in which the organs were arranged according to his peculiar classification of their functions but lived to publish only the first two volumes.[4]

Contributions and theories

Bichat's main contribution to medicine and physiology was his perception that the diverse body of organs contain particular tissues or membranes, and he described 21 such membranes, including connective, muscle, and nerve tissue.[6] Bichat did not use a microscope because he distrusted it, therefore his analyses did not include any acknowledgement of cellular structure.[6] Nonetheless, he formed an important bridge between the organ pathology of Giovanni Battista Morgagni and the cell pathology of Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow.

Vitalism

Famously, Bichat defined life as "those set of functions which resist death".[7]

He thought that life was separable into two parts: the organic life (also sometimes called the vegetative system)[6] and the animal life. The organic life was the life of the heart, intestines, and other organs. Bichat theorized that this life was regulated through the ganglionic nervous system, a collection of small independent "brains" in the chest cavity.[8]

In contrast, the animal life involved harmonious, symmetrical organs such as the eyes, ears, and limbs. It included habit and memory and was ruled by the wit and the intellect. This was the function of the brain itself, although it could not exist without the heart, the center of the organic life.[8]

Memorials

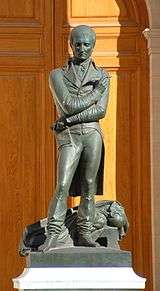

A large bronze statue of Bichat, work of the famous sculptor David D'Angers, was erected in 1857 in the main courtyard (Cour d'honneur) of the René Descartes University in 12, rue de l'Ecole de Médecine, Paris, thanks to the support of the members of the Medical Congress of France, which took place in 1845. On the pedestal can be read the following inscription: A Xavier Bichat. Le Congrès Médical de France de 1845.

Bichat's career is enthusiastically recounted in George Eliot's 1872 novel, Middlemarch. His name is also one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Michael Foucault has a chapter on Bichat in his The Birth of the Clinic.[9]

Gallery

- Bichat’s statue in the « Cour d’Honneur »

- The statue

Portrait

Portrait Portrait

Portrait At the University of Zaragoza, College of Medicine

At the University of Zaragoza, College of Medicine

See also

References

- 1 2 George F. Nafziger (2002). Historical Dictionary of the Napoleonic Era. Scarecrow Press. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-0-8108-4092-8. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- 1 2 John G. Simmons (2002). Doctors and Discoveries: Lives That Created Today's Medicine. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-0-618-15276-6. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 Pierre Auguste Béclard; Xavier Bichat (1823). Additions to the General anatomy of Xavier Bichat. Richardson and Lord. pp. 2–. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Elaut, L. (July 1969). "The theory of membranes of F. X. Bichat and his predecessors". Sudhoffs Archiv. West Germany. 53 (1): 68–76. ISSN 0039-4564. PMID 4241888.

- 1 2 3 Jon E. Roeckelein (1998). Dictionary of Theories, Laws, and Concepts in Psychology. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-0-313-30460-6. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ Jonathan Strauss (13 February 2012). Human Remains: Medicine, Death, and Desire in Nineteenth-Century Paris. Fordham Univ Press. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-0-8232-3379-3. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- 1 2 Stanley Finger (2001). Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function. Oxford University Press. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ Leon Chai (17 May 2006). Romantic Theory: Forms of Reflexivity in the Revolutionary Era. JHU Press. pp. 248–. ISBN 978-0-8018-8396-5. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bichat, Marie François Xavier". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bichat, Marie François Xavier". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Sources

- N.DOBO-A.ROLE, Bichat. La vie fulgurante d'un génie, Perrin, Paris 1989

- (French) Marie François Xavier Bichat's biography and works by the BIUM (Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine et d'odontologie, Paris), see its digital library Medic@.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marie François Xavier Bichat. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Marie François Xavier Bichat |

- Works by or about Marie François Xavier Bichat at Internet Archive

- Additions to the General Anatomy of Xavier Bichat Google ebook

- Physiological researches upon life and death Google ebook

- Some places and memories related to Xavier Bichat

- Physiological researches upon life and death by Xavier Bichat (1809)