Maria de Rudenz

Maria de Rudenz is a dramma tragico, or tragic opera, in three parts by Gaetano Donizetti. The Italian libretto was written by Salvadore Cammarano, based on "a piece of Gothic horror",[1] the 5-act French Gothic melodrama La Nonne Sanglante (Paris, 1835), by Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois and Julien de Mallian, and elements from The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis. It premiered at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice, on 30 January 1838. Soprano Caroline Ungher (1803-1877)---famously turning a deaf Beethoven around to receive the thunderous applause at the première of that composer's Ninth Symphony---created the eponymous rôle, and the towering Italian baritone Giorgio Ronconi as Corrado di Waldorf.

Performance History

19th Century

While the initial performances were not very successful (Donizetti regarded them as "a fiasco"),[2] the opera was withdrawn after two performances.[1] Yet subsequently, the opera enjoyed many other Italian productions in the years following the Venice première, the second being a couple months later in March, 1838, in Florence at the Teatro Pergola with the great Felice Varesi (1813-1889). He was not only the main rival to Ronconi, but the creator of Verdi's Macbetto, Rigoletto, and Germont, rôles modeled on and anticipated by the great Bellini and Donizetti baritone parts---including Corrado di Waldorf---created for these two seminal artists.

Other productions followed in Milan, Naples, Genoa, Turino, and Palermo. It was quite popular in Livorno with Verdi muse Giuseppina Strepponi in 1838, and enjoyed 14 successful performances in Rome at the storied Teatro Valle in 1841 with Marietta Albini (d. 1849), where an "excellent production and superior singing this time won vigorous approval."[2] (Albini was the second wife of the great bel canto composer Giovanni Pacini, appearing in many of his operas.) A notable Norma and famously replacing Strepponi in Nabucco, Teresa De Giuli-Bórsi (1817-1877)---a powerful soprano much admired by Verdi---picked this rôle for her appearance at Teatro La Scala in 1842.

For such a supposedly failed opera, Strepponi and Ronconi---two of opera's great legends---thought enough of it to revive it in five separate productions over the next four years---on the Livorno stage, at Florence in 1839 and Verona in 1840, and particularly successfully at Faenza and Ancona in 1841. Donizetti wrote of the Ancona staging: I read now of the success of Maria de Rudenz in Ancona, its very happy reception, and I still bleed for the severity with which they judged me in Venice. That the great bel canto baritone Giorgio Ronconi---the creator of Corrado---appeared opposite Strepponi in all of these productions, surely this is evidence of the esteem he felt for the rôle, and perhaps advocates for the opera's quality. The celebrated Italian soprano Teresa Brambilla (1813-1895), creator of Verdi's Gilda, and whose beautiful sister Marietta Brambilla created the rôle of Maffio Orsini in Donizetti's Lucrezia Borgia, had a popular success with the work in Rome at the Teatro Apollo in 1843, again with Ronconi in his seventh and last production of this opera. The creator of Amelia in Simon Boccanegra, the dramatic soprano Luigia Bendazzi (1829-1901) achieved a notable success in the role at the Teatro San Carlo in 1851, selecting it for the next production after her début; the success of this performance launched a major career.

The opera was produced every year since its premiere until 1867, mainly in Italy, but with productions in Madrid (1841), Corfu, Lisbon, Malta, Alexandria, Barcelona (1845), Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires. Its absence from London, Paris, and Vienna, though, is significant, but need not definitively discredit the work in a modern assessment.

Modern Performances

Today, the opera is very rarely staged. It did not receive a production in the UK until the Opera Rara concert presentation in London on 27 October 1974.[3] The first staged presentations in the 20th century took place at La Fenice beginning on 21 December 1980 with Katia Ricciarelli in the title role and Leo Nucci as Corrado[1] Both of these occasions have been recorded. The opera was successfully revived in 2016, on Oct. 28, 31, Nov. 3, and 6, at the Irish Wexford Opera Festival. The opera was lauded for it power, singular 'color' (tinta) and dark expressivity, while the singing of Gilda Fiume as Maria and Joo Wan Kang as Corrado was praised. Many critics found director Fabio Ceresa's highly ironic, modernistic, and even comedic approach to 19th C. Gothic melodrama effective and appropriate; George Hall, reviewing the Oct. 28th performance (thestage.co.uk, Oct. 31), dissented:

"Moving the action forward to the period of composition, Ceresa and his team fill the stage up with all sorts of unnecessary contrivance that clogs up the piece’s dramatic wheels. McCann’s set is enormous and cumbersome, a multi-level structure whose individual sections must be a nightmare to move around on the Wexford stage, and in whose multiple rooms there is far too much extraneous activity. There is an obsessive amount of weird headgear worn by all the characters, especially the chorus, while someone should discretely dispose of the characters’ puppet doubles."

Roles

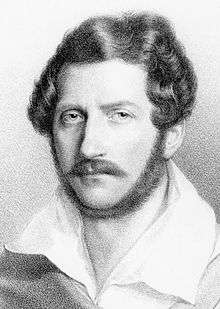

Napoleone Moriani (by Joseph Kriehuber)

| Role | Voice type | Premiere Cast, 30 January 1838 (Conductor: — ) |

|---|---|---|

| Maria de Rudenz | soprano | Carolina Ungher |

| Matilde di Wolf, her cousin | soprano | Isabella Casali |

| Corrado Waldorf | baritone | Giorgio Ronconi |

| Enrico, his brother | tenor | Napoleone Moriani |

| Rambaldo, old relative of the Rudenz house | bass | Domenico Raffaeli |

| The Chancellor of Rudenz | tenor | Alessandro Giacchini |

| Knights, squires, and vassals of the Rudenz house | ||

Synopsis

- Place: Switzerland

- Time: 1400[1]

PART 1---A room in an inn on the river Aar. We see the convent of Arau and the Castle of Rudenz on the further shore through the windows. Dawn is breaking. Matilde de Wolff (orphaned cousin of Maria de Rudenz) and the nuns can be heard praising God’s majesty in nature. Corrado expresses his love of Matilde and how it saved him from misery in a ‘hit’ aria of the 19th C. concert stage, Ah! Non avea più lagrime. Corrado di Waldorf tells his brother Enrico that, having his proposal of marriage to Maria rejected by her father, they fled to Venice, but one night he saw her descend into the garden to meet a waiting man! In revenge, he abandoned her retributively in the catacombs of Rome. After paying a man gold to lead Maria out of the catacombs, he wandered abroad distractedly, until returning home to fall in love with Matilde, (duetto) Qui di mie pene un angelo. She is about to inherit the castle that very day from Maria’s father, Count Piero di Rudenz---who died brokenhearted believing his absent daughter was dead. Enrico reveals a secret love for Maria and his conflicted, tormented feelings toward his brother.

---In the gloomy castle, Rambaldo, a trusty old retainer---and the man in the Venice garden---believes Maria has died in Rome as reported. Eventually he sees a ghost-like woman, prostrate in the shadows, weeping in front of the late Count of Rudenz’s portrait. Entering through the castle’s secret underground passages, Maria has returned home from Rome, seeking Corrado. Rambaldo reveals that Corrado’s father died an assassin on the scaffold and Matilde is to be married, but omits the identity of the bridegroom as Corrado. Maria expresses her desire to retire into the convent to pray for forgiveness, (aria) Si, del chiostro penitente. She tells Rambaldo that she will soon die unseen to the world, and that he should tell Corrado that she will have died loving him.

---Everyone gathers to hear the will of the Count Rudenz, but the retainers want Maria de Rudenz back as mistress. The Cancelliere reads the will, which stipulates that if Maria fails to return in a year, Matilde inherits the castle, Maria having disappeared exactly one year ago to the day. Just as Corrado declares his love for Matilde, Maria---clearly reassessing her recent magnanimity---enters sensationally to stop the marriage and the inheritance! In a magnificent concertato larghetto, Chiuse al di per te le ciglia, Maria announces that it was Corrado's treachery that killed her father. Her retainers enthusiastically rally in support, (coro) Maria, di fidi sudditi. Maria expresses her intention that Corrado will lose Matilde to the cloister, declares herself avenged, and drags Matilde away.

PART 2---Maria tells Rambaldo to secure the castle against a rescue attempt of Matilde from Corrado. Enrico explains his love of Matilde, and asks for her release from captivity. He expresses mingled love and hatred of his own brother in an aria, Talor nel mio delirio. Maria says that she may be able to unite him with Matilde because of the mysterious knowledge she has about Corrado. Alone, Maria tells Corrado that he must relinquish Matilde to his brother, and that his father, Ugo di Berna, was beheaded on the German coast as a notorious assassin! Ugo, when he was banished, had left Corrado as a baby with a trusted friend, who raised him as his own. She will keep these secrets only if she returns to her as they once were, as she declares her love in duetto, Fonte d’amare lagrime. Maria tells him that if he marries Matilde, she should just kill her now with his sword, but that he won't enjoy the wedding night---she will rise up as a ghost, dripping with blood. Corrado rejects this, and Maria reminds him of the sinister, Borgia-like ancestral history of the castle, as she threatens to throw Matilde into the pit she reveals under a trap door. Incensed, Corrado finally stabs Maria. The retainers and Matilde rush in, and Maria declares that she has stabbed herself. All then exclaim over the body of the (apparently) poor expired woman.

PART 3---An atrium in the castle; a chapel to one side lit up within. At the back a view of the park lapped by water. The moon is shining. The castle retainers remark ominously that a dark-mantled ghost with streaming hair has been seen near the chapel, Enrico has fled, and that Corrado is to marry Matilde. Enrico returns unexpectedly, and Rambaldo tells him it’s too late, as Corrado has just now married Matilde. Enrico has received a mysterious letter which reveals that Corrado deliberately kept Enrico in the dark concerning Ugo di Berna and that he knew all along about his love for Matilde. Corrado appears with the wedding party, who move on, leaving him alone. Enraged, Enrico tells him that he now knows everything, and will destroy his marriage, (duetto) A me, cui finance la speme togliesti. The knights enter, requesting Corrado’s return to Matilde. Enrico announces that Corrado is a villain and the son of a murderer, rips the insignia of the Counts of Rudenz from Corrado, and tramples it. Enrico insists that his brother must die, bathed in his blood, over Matilde, (duetto) O tremenda gelosia. The two men rush off furiously to duel in the park.

---Matilde’s ladies praise her beauty in a hall splendid with garlands of flowers, torches and dancing, adjacent to the nuptial chamber. Unseen by all, a masked woman upstage enters the bridal chamber unseen. A page speaks to Matilde, who retires to the chamber. Corrado enters, and all leave; he throws his sword out of the window. A scream is heard from the chamber, and rushing towards it, Corrado is stopped by a mantled and veiled Maria. “I told you I should rise again from the tomb!” Medea-like, she gloats that Corrado should have fled the wedding chapel, and that he should see what she has left him inside, (aria) Mostro iniquo, tremar tu dovevi. Corrado returns from the chamber, exclaiming that Matilde has been stabbed to death. Everyone returns, and dropping her veil, Maria reveals that Rambaldo had just sealed her tomb, when a low groan made him realize she still lived, but has kept this secret. Corrado attempts to stab her, but is restrained. In a slow cabaletta, Al misfatto enorme e rio, she reveals her mad love for Corrado and the reasons behind her terrible revenge upon him and Matilde: "But when an immense love is outraged/It knows neither law nor limit." Resisting help, she tears her bandages away from her wound, admitting what will be her own ignominious legacy (just as was Ugo di Berna’s). Rambaldo alone, she says, will remain to cast a flower on her 'infame tomba.' She admits that she still loves him. The company recoils at this 'notte di terror.' Corrado---deeply moved---regretting he must live, makes to embrace her, as the most tragic Maria de Rudenz falls dead at his feet.

Literary Sources

Non ha legge, né confine/Oltraggiato, immenso amor.---Maria de Rudenz

Salvadore Cammarano based his libretto on a 5-act French play, La Nonne sanglante, by Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois and Julien de Mallian, which premiered Feb. 17, 1835 in Paris, at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin. The melodrama was very successful in its day; the legendary actress Mademoiselle Georges created the role of Marie de Rudenz. The melodrama derives only its title, imagery, and some motifs from the wildly popular Gothic novel of Matthew Lewis, The Monk, while otherwise straying from the book's explicit plot line. The selection of this play as their source, with its extreme Gothic sensibility, shows just how au courant Donizetti and his librettist really were with the Romantic movement in music and literature.

Recordings

| Year | Cast: Maria de Rudenz, Matilde di Wolf, Corrado Waldorf, Enrico |

Conductor, Opera House and Orchestra |

Label[4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 | Ludmilla (Milla) Andrew, Merril Jenkins, Christian Du Plessis, Richard Greager |

Alun Francis, Philomusica of London and the Opera Rara Chorus, (Recording of a concert performance in the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, 27 October) |

CD: Memories, Cat: HR 4588-4589 |

| 1981 | Katia Ricciarelli, Silvia Baleani, Leo Nucci, Alberto Cupido |

Eliahu Inbal, Orchestra and Chorus of Teatro La Fenice, Venice, (Recorded at the La Fenice, Venice, January) |

CD: Fonit Cetra «Italia» Cat: CDC 91 Mondo Musica, Cat: MFOH 10708 Living Stage, Cat: LS 35140 |

| 1997 | Nelly Miricioiu, Robert McFarland, Bruce Ford, Matthew Hargreaves |

David Parry, Philharmonia Orchestra and the Geoffrey Mitchell Choir |

CD: Opera Rara, Cat: ORC16 |

References

Notes

Sources

- Allitt, John Stewart (1991), Donizetti: in the light of Romanticism and the teaching of Johann Simon Mayr, Shaftesbury: Element Books, Ltd (UK); Rockport, MA: Element, Inc.(USA)

- Ashbrook, William (1982), Donizetti and His Operas, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23526-X

- Ashbrook, William (1998), "Donizetti, Gaetano" in Stanley Sadie (Ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Vol. Three, pp. 201–203. London: MacMillan Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-333-73432-7 ISBN 1-56159-228-5

- Ashbrook, William and Sarah Hibberd (2001), in Holden, Amanda (Ed.), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 0-14-029312-4. pp. 224 – 247.

- Black, John (1982), Donizetti’s Operas in Naples, 1822—1848. London: The Donizetti Society.

- Loewenberg, Alfred (1970). Annals of Opera, 1597-1940, 2nd edition. Rowman and Littlefield

- Osborne, Charles, (1994), The Bel Canto Operas of Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini, Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-71-3

- Sadie, Stanley, (Ed.); John Tyrell (Exec. Ed.) (2004), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 2nd edition. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-19-517067-2 (hardcover). ISBN 0-19-517067-9 OCLC 419285866 (eBook).

- Weinstock, Herbert (1963), Donizetti and the World of Opera in Italy, Paris, and Vienna in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, New York: Pantheon Books. LCCN 63-13703

External links

- Donizetti Society (London) website

- La nonne sanglante, drame en cinq actes (1835)

- Forgotten Opera Singers Blog