Mabinogion

The Mabinogion (/ˌmæbəˈnoʊɡiən/; Welsh pronunciation: [mabɪˈnɔɡjɔn]) are the earliest prose literature of Britain. The stories were compiled in the 12th–13th centuries from earlier oral traditions by medieval Welsh authors. The two main source manuscripts were created c. 1350–1410, as well as some earlier fragments. But beyond their origins, first and foremost these are fine quality storytelling, offering high drama, philosophy, romance, tragedy, fantasy, sensitivity, and humour; refined through long development by skilled performers.

The title covers a collection of eleven prose stories of widely different types. There is a classic hero quest: Culhwch and Olwen. Historic legend in Lludd and Llefelys glimpses a far off age, and other tales portray a very different King Arthur than the later popular versions do. The highly sophisticated complexity of the Four Branches of the Mabinogi defy categorisation. The list is so diverse a leading scholar has challenged them as a true collection at all.[1]

Early scholars from the 18th century to the 1970s predominantly viewed the tales as fragmentary pre-Christian Celtic mythology,[2] or in terms of international folklore.[3] There are certainly traces of mythology, and folklore components, but since the 1970s[4] an understanding of the integrity of the tales has developed, with investigation of their plot structures, characterisation, and language styles. They are now seen as a sophisticated narrative tradition, both oral and written, with ancestral construction from oral storytelling,[5] and overlay from Anglo-French influences.

The first modern publications were English translations of several tales by William Owen Pughe in journals 1795, 1821, 1829.[6] However it was Lady Charlotte Guest 1838–45 who first published the full collection, and bilingually in both Welsh and English. She is often assumed to be responsible for the name "Mabinogion" but this was already in standard use since the 18th century. Indeed, as early as 1632 the lexicographer John Davies quotes a sentence from Math fab Mathonwy with the notation "Mabin." in his Antiquae linguae Britannicae . . . dictionarium duplex, article "Hob". The later Guest translation of 1877 in one volume, has been widely influential and remains actively enjoyed today.[7] The most recent translation a compact version by Sioned Davies.[8] John Bollard has published a series of volumes between with his own translation, with copious photography of the sites in the stories.[9] The tales continue to inspire new fiction,[10] dramatic retellings,[11] visual artwork, and research. [12]

Etymology

The name first appears in 1795 in William Owen Pughe's translation in the journal Cambrian Register: "The Mabinogion, or Juvenile Amusements, being Ancient Welsh Romances." The name appears to have been current among Welsh scholars of the London Welsh Societies and the regional Welsh eisteddfodau. It was inherited as the title by the first publisher of the complete collection, Lady Charlotte Guest. The form mabynnogyon occurs once at the end of the first of the Four Branches of the Mabinogi in one manuscript. It is now generally agreed that this one instance was a mediaeval scribal error which assumed 'mabinogion' was the plural of 'mabinogi.' But 'mabinogi' is already a Welsh plural, which occurs correctly at the end of the remaining three branches.

The word mabinogi itself is something of a puzzle, although clearly derived from the Welsh mab, which means "son, boy, young person". Eric P. Hamp of the earlier school traditions in mythology, found a suggestive connection with Maponos a Celtic deity of Gaul, ("the Divine Son"). The "Mabinogi" properly applies only to the Four Branches, which is a tightly organised quartet very likely by one author, where the other seven are so very diverse (see below). Each of these four tales ends with a colophon meaning "thus ends this branch of the Mabinogi" (in various spellings), hence the name.

Translations

Lady Charlotte Guest's work was helped by the earlier research and translation work of William Owen Pughe.[13] The first part of Charlotte Guest's translation of the Mabinogion appeared in 1838, and it was completed in seven parts in 1845.[14] A three-volume edition followed in 1846,[15] and a revised edition in 1877. Her version of the Mabinogion remained standard until the 1948 translation by Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones, which has been widely praised for its combination of literal accuracy and elegant literary style.[16][17] Several more, listed below, have since appeared.

Date of stories

The question of the dates of the tales in the Mabinogion is important, because if they can be shown to have been written before Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae and the romances of Chrétien de Troyes, then some of the tales, especially those dealing with Arthur, would provide important evidence for the development of Arthurian legend. Regardless, their importance as records of early myth, legend, folklore, culture, and language of Wales is immense.

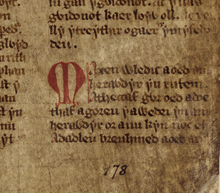

The stories of the Mabinogion appear in either or both of two medieval Welsh manuscripts, the White Book of Rhydderch or Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch, written circa 1350, and the Red Book of Hergest or Llyfr Goch Hergest, written about 1382–1410, though texts or fragments of some of the tales have been preserved in earlier 13th century and later manuscripts. Scholars agree that the tales are older than the existing manuscripts, but disagree over just how much older. It is clear that the different texts included in the Mabinogion originated at different times. Debate has focused on the dating of the Four Branches of the Mabinogi. Sir Ifor Williams offered a date prior to 1100, based on linguistic and historical arguments, while later Saunders Lewis set forth a number of arguments for a date between 1170 and 1190; Thomas Charles-Edwards, in a paper published in 1970, discussed the strengths and weaknesses of both viewpoints, and while critical of the arguments of both scholars, noted that the language of the stories best fits the 11th century, although much more work is needed. More recently, Patrick Sims-Williams argued for a plausible range of about 1060 to 1200, which seems to be the current scholarly consensus.

Stories

| Part of a series on |

| Celtic mythology |

|---|

|

| Gaelic mythology |

| Brythonic mythology |

| Concepts |

| Religious vocations |

| Festivals |

|

The collection represents the vast majority of prose found in medieval Welsh manuscripts which is not translated from other languages. Notable exceptions are the Areithiau Pros. None of the titles are contemporary with the earliest extant versions of the stories, but are on the whole modern ascriptions. The eleven tales are not adjacent in either of the main early manuscript sources, the White Book of Rhydderch (c. 1375) and the Red Book of Hergest (c. 1400), and indeed Breuddwyd Rhonabwy is absent from the White Book.

Four Branches of the Mabinogi

The Four Branches of the Mabinogi (Pedair Cainc y Mabinogi) are the most clearly mythological stories contained in the Mabinogion collection. Pryderi appears in all four, though not always as the central character.

- Pwyll Pendefig Dyfed (Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed) tells of Pryderi's parents and his birth, loss and recovery.

- Branwen ferch Llŷr (Branwen, daughter of Llŷr) is mostly about Branwen's marriage to the King of Ireland. Pryderi appears but does not play a major part.

- Manawydan fab Llŷr (Manawydan, son of Llŷr) has Pryderi return home with Manawydan, brother of Branwen, and describes the misfortunes that follow them there.

- Math fab Mathonwy (Math, son of Mathonwy) is mostly about Math and Gwydion, who come into conflict with Pryderi.

Native tales

Also included in Lady Guest's compilation are five stories from Welsh tradition and legend:

- Breuddwyd Macsen Wledig (The Dream of Macsen Wledig)

- Lludd a Llefelys (Lludd and Llefelys)

- Culhwch ac Olwen (Culhwch and Olwen)

- Breuddwyd Rhonabwy (The Dream of Rhonabwy)

- Hanes Taliesin (The Tale of Taliesin)

The tales Culhwch and Olwen and The Dream of Rhonabwy have interested scholars because they preserve older traditions of King Arthur. The subject matter and the characters described events that happened long before medieval times. After the departure of the Roman Legions, the later half of the fifth century was a difficult time in Britain. King Arthur's twelve battles and defeat of invaders and raiders are said to have culminated in the Battle of Bath. There is no consensus about the ultimate meaning of The Dream of Rhonabwy. On one hand it derides Madoc's time, which is critically compared to the illustrious Arthurian age. However, Arthur's time is portrayed as illogical and silly, leading to suggestions that this is a satire on both contemporary times and the myth of a heroic age.[18]

Rhonabwy is the most literary of the medieval Welsh prose tales. It may have also been the last written. A colophon at the end declares that no one is able to recite the work in full without a book, the level of detail being too much for the memory to handle. The comment suggests it was not popular with storytellers, though this was more likely due to its position as a literary tale rather than a traditional one.[19]

The tale The Dream of Macsen Wledig is a romanticized story about the Roman Emperor Magnus Maximus. Born in Spain, he became a legionary commander in Britain, assembled a Celtic army and assumed the title of Emperor of the Western Roman Empire in AD 383. He was defeated in battle in 385 and beheaded at the direction of the Eastern Roman Emperor.

The story of Taliesin is a later survival, not present in the Red or White Books, and is omitted from many of the more recent translations.

Romances

The three tales called The Three Romances (Y Tair Rhamant) are Welsh versions of Arthurian tales that also appear in the work of Chrétien de Troyes. Critics have debated whether the Welsh Romances are based on Chrétien's poems or if they derive from a shared original. Though it is arguable that the surviving Romances might derive, directly or indirectly, from Chrétien, it is probable that he in turn based his tales on older, Celtic sources. The Welsh stories are not direct translations and include material not found in Chrétien's work.

- Owain, neu Iarlles y Ffynnon (Owain, or the Countess of the Fountain)

- Peredur fab Efrog (Peredur, son of Efrawg)

- Geraint ac Enid (Geraint and Enid)

Influence on later works

- Kenneth Morris, himself a Welshman, pioneered the adaptation of the Mabinogion into fantasy with The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed (1914) and Book of the Three Dragons (1930).

- Evangeline Walton adapted the Mabinogion into the novels The Island of the Mighty (1936), The Children of Llyr (1971), The Song of Rhiannon (1972) and Prince of Annwn (1974), each one of which she based on one of the branches, although she began with the fourth and ended by telling the first. These were published together in chronological sequence as The Mabinogion Tetralogy in 2002.

- Y Mabinogi is a film version, produced in 2003. It starts with live-action among Welsh people in the modern world. They then 'fall into' the legend, which is shown through animated characters. It conflates some elements of the myths and omits others.

- The tale of "Culhwch and Olwen" was adapted by Derek Webb in Welsh and English as a dramatic recreation for the reopening of Narberth Castle in Pembrokeshire in 2005.

- Lloyd Alexander's award-winning The Chronicles of Prydain, which are fantasies for younger readers, are loosely based on Welsh legends found in the Mabinogion. Specific elements incorporated within Alexander's books include the Cauldron of the Undead, as well as adapted versions of important figures in the Mabinogion such as Prince Gwydion and Arawn, Lord of the Dead.

- Alan Garner's novel The Owl Service (Collins, 1967; first US edition Henry Z. Walck, 1968)

- The Welsh mythology of The Mabinogion, especially the Four Branches of the Mabinogi is important in John Cowper Powys's novels Owen Glendower (1941), and Porius (1951).[20] Jeremy Hooker sees The Mabinogion as having "a significant presence […] through character's knowledge of its stories and identification of themselves or others with figures or incidents in the stories".[21] Indeed there are "almost fifty allusions to these four […] tales"' (The Four Branches of the Mabinogi) in the novel, though "some that are fairly obscure and inconspicuous".[22] Also in Porius Powys creates the character Sylvannus Bleheris, Henog of Dyfed, author of the Four Pre-Arthurian Branches of the Mabinogi concerned with Pryderi, as a way linking the mythological background of Porius with this aspect of the Mabinogion.[23]

See also

- Medieval Welsh literature

- Christopher Williams painted three paintings from the Mabinogion. Branwen (1915) can be viewed at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea. Blodeuwedd (1930) is at the Newport Museum and Art Gallery. The third painting in the series is Ceridwen (1910).

- The Chronicles of Prydain

- Mabinogion sheep problem

References

- ↑ Bollard, John Kenneth. 2007. "What Is The Mabinogi? What Is 'The Mabinogion'?" https://sites.google.com/site/themabinogi/mabinogiandmabinogion

- ↑ Notably Matthew Arnold; William J. Gruffydd.

- ↑ Jackson, Kenneth Hurlstone. 1961. The International Popular Tale and the Early Welsh Tradition. The Gregynog Lectures. Cardiff: CUP.

- ↑ Bollard 1974; Gantz 1978; Ford 1981.

- ↑ See various works by Sioned Davies e.g. 1. Davies, Sioned. 1998. "Written Text as Performance: The Implications for Middle Welsh Prose Narratives." In Literacy in Medieval Celtic Societies, 133–48. and 2. Davies, Sioned. 2005. "'He Was the Best Teller of Tales in the World': Performing Medieval Welsh Narrative." In Performing Medieval Narrative, 15–26. Cambridge: Brewer.

- ↑ 1. Pughe, William Owen. 1795. "The Mabinogion, or Juvenile Amusements, Being Ancient Welsh Romances." Cambrian Register, 177–87. 2. Pughe, William Owen. 1821. "The Tale of Pwyll." Cambro-Briton Journal 2 (18): 271–75. . 3. Pughe, William Owen. 1829. "The Mabinogi: Or, the Romance of Math Ab Mathonwy." The Cambrian Quarterly Magazine and Celtic Repository 1: 170–79.

- ↑ Available online since 2004. Guest, Charlotte. 2004. "The Mabinogion. (Gutenberg, Guest)." Gutenberg. http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/gutbook/lookup?num=5160.

- ↑ Davies, Sioned. 2007. The Mabinogion. Oxford: OUP.

- ↑ 1. Bollard, John Kenneth. 2006. Legend and Landscape of Wales: The Mabinogi. Llandysul, Wales: Gomer Press. 2. Bollard, John Kenneth. 2007. Companion Tales to The Mabinogi. Llandysul, Wales: Gomer Press. 3. Bollard, John Kenneth. 2010. Tales of Arthur: Legend and Landscape of Wales. Llandysul, Wales: Gomer Press. Photography by Anthony Griffiths.

- ↑ For example the Seren series 2009–2014, but the earliest reinterpretations were by Evangeline Walton starting 1936..

- ↑ e.g. Robin Williams; Daniel Morden.

- ↑ "BBC – Wales History – The Mabinogion". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ↑ "Guest (Schreiber), Lady Charlotte Elizabeth Bertie". The National Library opf Wales: Dictionary of Welsh biography. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ "BBC Wales History – Lady Charlotte Guest". BBC Wales. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ "Lady Charlotte Guest. extracts from her journal 1833 – 1852". Genuki: UK and Ireland Genealogy. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ "Lady Charlotte Guest". Data Wales Index and search. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Stephens, Meic, ed. (1986). The Oxford Companion to the Literature of Wales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 306, 326. ISBN 0-19-211586-3.

- ↑ Roberts, Brynley F. (1991). "The Dream of Rhonabwy." In Lacy, Norris J., The New Arthurian Encyclopedia, p. 120–121. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-4377-4.

- ↑ Lloyd-Morgan, Ceridwen. (1991). "'Breuddwyd Rhonabwy' and Later Arthurian Literature." In Bromwich, Rachel, et al., "The Arthur of the Welsh", p. 183. Cardiff: University of Wales. ISBN 0-7083-1107-5.

- ↑ John Brebner describes The Mabinogion "as "indispensable for understanding Powys's later novels", by which he means Owen Glendower and Porius (fn, p. 191).

- ↑ "John Cowper Powys: 'Figure of the Marches'", in his Imagining Wales (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2001), p. 106.

- ↑ W. J. Keith, p. 44.

- ↑ John Cowper Powys, "The Characters of the Book", Porius, p. 18.

Bibliography

- Translations and retellings

- Bollard, John K. (translator), and Anthony Griffiths (photographer). Tales of Arthur: Legend and Landscape of Wales. Gomer Press, Llandysul, 2010. ISBN 978-1-84851-112-5. (Contains "The History of Peredur or The Fortress of Wonders", "The Tale of the Countess of the Spring", and "The History of Geraint son of Erbin", with textual notes.)

- Bollard, John K. (translator), and Anthony Griffiths (photographer). Companion Tales to The Mabinogi: Legend and Landscape of Wales. Gomer Press, Llandysul, 2007. ISBN 1-84323-825-X. (Contains "How Culhwch Got Olwen", "The Dream of Maxen Wledig", "The Story of Lludd and Llefelys", and "The Dream of Rhonabwy", with textual notes.)

- Bollard, John K. (translator), and Anthony Griffiths (photographer). The Mabinogi: Legend and Landscape of Wales. Gomer Press, Llandysul, 2006. ISBN 1-84323-348-7. (Contains the Four Branches, with textual notes.)

- Davies, Sioned. The Mabinogion. Oxford World's Classics, 2007. ISBN 1-4068-0509-2. (Omits "Taliesin". Has extensive notes.)

- Ellis, T. P., and John Lloyd. The Mabinogion: a New Translation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1929. (Omits "Taliesin"; only English translation to list manuscript variants.)

- Ford, Patrick K. The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977. ISBN 0-520-03414-7. (Includes "Taliesin" but omits "The Dream of Rhonabwy", "The Dream of Macsen Wledig" and the three Arthurian romances.)

- Gantz, Jeffrey. Trans. The Mabinogion. London and New York: Penguin Books, 1976. ISBN 0-14-044322-3. (Omits "Taliesin".)

- Guest, Lady Charlotte. The Mabinogion. Dover Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-486-29541-9. (Guest omits passages which only a Victorian would find at all risqué. This particular edition omits all Guest's notes.)

- Jones, Gwyn and Jones, Thomas. The Mabinogion. Golden Cockerel Press, 1948. (Omits "Taliesin".)

- Everyman's Library edition, 1949; revised in 1989, 1991.

- Jones, George (Ed), 1993 edition, Everyman S, ISBN 0-460-87297-4.

- 2001 Edition, (Preface by John Updike), ISBN 0-375-41175-5.

- Knill, Stanley. The Mabinogion Brought To Life. Capel-y-ffin Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-1-4895-1528-5. (Omits Taliesin. A retelling with General Explanatory Notes.) Presented as prose but comprising 10,000+ lines of hidden decasyllabic verse.

- Welsh text and editions

- Branwen Uerch Lyr. Ed. Derick S. Thomson. Medieval and Modern Welsh Series Vol. II. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1976. ISBN 1-85500-059-8

- Breuddwyd Maxen. Ed. Ifor Williams. Bangor: Jarvis & Foster, 1920.

- Breudwyt Maxen Wledig. Ed. Brynley F. Roberts. Medieval and Modern Welsh Series Vol. XI. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 2005.

- Breudwyt Ronabwy. Ed. Melville Richards. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1948.

- Culhwch and Olwen: An Edition and Study of the Oldest Arthurian Tale. Rachel, Bromwich and D. Simon Evans. Eds. and trans. Aberystwyth: University of Wales, 1988; Second edition, 1992.

- Cyfranc Lludd a Llefelys. Ed. Brynley F. Roberts. Medieval and Modern Welsh Series Vol. VII. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1975.

- Historia Peredur vab Efrawc. Ed. Glenys Witchard Goetinck. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. 1976.

- Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch. Ed. J. Gwenogvryn Evans. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1973.

- Math Uab Mathonwy. Ed. Ian Hughes. Aberystwyth: Prifysgol Cymru, 2000.

- Owein or Chwedyl Iarlles y Ffynnawn. Ed. R.L. Thomson. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1986.

- Pedeir Keinc y Mabinogi. Ed. Ifor Williams. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1951. ISBN 0-7083-1407-4

- Pwyll Pendeuic Dyuet. Ed. R. L. Thomson. Medieval and Modern Welsh Series Vol. I. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1986. ISBN 1-85500-051-2

- Ystorya Gereint uab Erbin. Ed. R. L. Thomson. Medieval and Modern Welsh Series Vol. X. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1997.

- Ystoria Taliesin. Ed. Patrick K. Ford. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1992. ISBN 0-7083-1092-3

Secondary sources

- Charles-Edwards, T.M. "The Date of the Four Branches of the Mabinogi" Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (1970): 263–298.

- Ford, Patrick K. "Prolegomena to a Reading of the Mabinogi: 'Pwyll' and 'Manawydan.'" Studia Celtica, 16/17 (1981–82): 110–25.

- Ford, Patrick K. "Branwen: A Study of the Celtic Affinities," Studia Celtica 22/23 (1987/1988): 29–35.

- Hamp, Eric P. "Mabinogi." Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (1974–1975): 243–249.

- Sims-Williams, Patrick. "The Submission of Irish Kings in Fact and Fiction: Henry II, Bendigeidfran, and the dating of the Four Branches of the Mabinogi", Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies, 22 (Winter 1991): 31–61.

- Sullivan, C. W. III (editor). The Mabinogi, A Books of Essays. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996. ISBN 0-8153-1482-5

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mabinogion |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article Mabinogion. |

There is a new, extensively annotated translation of the four branches of the Mabinogi proper by Will Parker at

The Guest translation can be found with all original notes and illustrations at:

The original Welsh texts can be found at:

- Mabinogion (an 1887 edition at the Internet Archive; contains all the stories except the "Tale of Taliesin")

- Mabinogion (Contains only the four branches reproduced, with textual variants, from Ifor Williams' edition.)

- Pwyll Pendeuic Dyuet

- Branwen uerch Lyr

- Manawydan uab Llyr

Versions without the notes, presumably mostly from the Project Gutenberg edition, can be found on numerous sites, including:

- Project Gutenberg Edition of The Mabinogion (From the 1849 edition of Guest's translation)

- The Arthurian Pages: The Mabinogion

- Branwaedd: Mabinogion

- Timeless Myths: Mabinogion

-

The Mabinogion public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Mabinogion public domain audiobook at LibriVox

A discussion of the words Mabinogi and Mabinogion can be found at

A theory on authorship can be found at