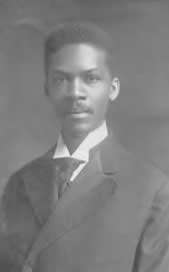

Louis George Gregory

Louis George Gregory (born June 6, 1874 in Charleston, South Carolina; died July 30, 1951 in Eliot, Maine) was a prominent member of the Bahá'í Faith posthumously appointed a Hand of the Cause, the highest appointed position in the Bahá'í Faith, by Shoghi Effendi.

Early years

Pre-college

He was born on June 6, 1874 to African-American parents liberated during the Civil War whose number included his future stepfather 1st Sgt. George Gregory.[1] His mother was Mary Elizabeth whose mother, Mary, was African and whose father was an enslaver named George Washington Dargan of the Rough Fork plantation in Darlington, South Carolina. When Gregory was four years old, his father, Ebaneezer George died. At seven years of age, Louis was witness to the savage lynching of his grandfather who had taken the family in and who had succeeded in a blacksmith business. Then his mother remarried to George Gregory, who was the only freeman of African descent to join the Union Army from the 3000 in Charleston at the time. George Gregory rose to 1st Sgt. in the 104th United States Colored Troops(USCT) after being recruited by Major Delaney, of African descent. After the war, he was honorifically called Colonel Gregory and his family received a Civil War pension. At this point Louis George Gregory took the name of his step father. Due to his military service, his step-son Louis George Gregory, was introduced in family situations to make friends with the European descent children of Army officers who would visit the home. George Gregory was also a leader in the community, playing a significant role in the inter-racial United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America that upon his death in 1929, the Union put out an advertisement in the Charleston Newspaper asking all Union members to attend, 1000 of both races did make it to Monrovia Union Cemetery, where headstones to George and Mary Elizabeth stand to this day.

During his elementary schooling, Gregory attended the first public school that was open to both African Americans and whites in Charleston, South Carolina. George and Mary Elizabeth were desperate for a child together, but after many infant deaths, tragically Mary Elizabeth died in 1891 after suffering an illness while giving birth to another infant death three months earlier. To add to Louis' tragedy his older brother Theodore also died the same year. Despite all of that, at the Avery Institute, the leading school for Americans of African descent in Charleston, Louis not only still graduated, but gave the graduation speech entitled, "Thou Shalt Not Live For Thyself Alone." Avery Institute still remembers Louis George Gregory to this day, by prominently displaying his portrait in their preserved classroom.

Significantly, at this point Louis gained a step brother Harrison Gregory, as his step-father remarried Lauretta Gregory. Lauretta's own husband, civil war veteran Louis Noisette had died while she was pregnant with Harrison. The Noisette family is a prominent Charleston family, that hails from Haiti, and may help explain why Louis chose Haiti as his future pioneering home in the 1930s. Philippe Stanislas Noisette was the young son of a Nantes, France horticulturalist for the King of France, and was sent to Haiti to send back exotic flowers. While there he married Celestine, a Haitian of African descent. They fled the violence of the Haitian Revolution to Charleston, SC together with two of Celestine's family members. Because of the miscegenation laws of South Carolina, Philippe was forced to declare Celestine a slave in order to continue to live together. They had six children together. In 1809 there is a record of a refusal of his request to liberate one of the family members through manumission. One of the two men fathered Benjamin who became enslaved by the Solomon family. Benjamin's children recorded in a 1893 deposition that throughout their enslavement their father made clear to them to remember their last name was Noisette rather than that of their enslaver. Harrison escaped enslavement in 1862 and joined the Union Navy on May 6, 1862 in Port Royal, SC. Benjamin also escaped enslavement in 1862 and went on to the freeman's Camp Barker, as it was known then, in Washington DC. And finally Louis' step-brothers father Louis Noisette remained enslaved until African American soldiers liberated Charleston in February 1865.[2] He then joined the 33rd USCT Regiment as a drummer to help liberate his mother and sister who remained enslaved in Savannah. After the war Louis Noisette married Lauretta, and had the child Harrison Noisette who became Harrison Gregory.

University and professional years

Gregory's generous step-father paid for his first year at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee where he studied English literature. Using the tailoring skills his mother had taught him he managed to manage the finances needed for the rest of his bachelor's degree. There being no law schools which would accept him in the south, he continued on to Howard University in Washington D.C., one of the few universities to accept black graduate students, to study law and received his LL.B degree in Spring 1902.[3] He was admitted to the bar,[4] and along with another young lawyer, James A. Cobb, opened a law office in Washington D.C. The partnership ended in 1906, after Gregory started to work in the United States Department of the Treasury.[5] In 1904 Gregory was listed as a supporter of the committee for a celebration of Booker T Washington.[6] In 1906 Gregory served as vice president of the Howard University Law School Alumni association.[7] Gregory had been attracted to the Niagara Movement[8] and active in the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, a Negro organization devoted to discussing issues of the day - he had been elected a vice president in 1907[9] and president in 1909.[10] Meanwhile, Gregory was visible in the newspapers over racist incidents.[11]

As a Bahá'í

Encountering the religion

At the Treasury Department Gregory met Thomas H. Gibbs, with whom he formed a close relationship. Gibbs, while not being a Bahá'í himself, shared information about the religion to Gregory, and Gregory attended a lecture by Lua Getsinger, a leading Bahá'í, in 1907.[12] In that meeting he met Pauline Hannen and her husband who invited him to many other meetings through the next couple of years and Gregory was much affected by the behavior of the Hannens and the religion after having become disillusioned with Christianity.[8] Among the readings Gregory reviewed on the religion was an early edition of The Hidden Words and the meetings were also held among the poor at a school and a Bahá'í view of Christian scripture and prophecy much affected him and presented a framework for a reformulation of society. While the Hannens went on pilgrimage in 1909 by visiting `Abdu'l-Bahá, then head of the religion, in Palestine, Gregory left the Treasury Department and established his practice in Washington D.C. When the Hannens returned, Gregory once again started attending meetings on the religion and the burgeoning Bahá'í community of DC was holding more and more meetings - particularly integrated meetings of the Hannens and some others.[8] `Abdu'l-Bahá also began to communicate either in letters or to those that visited on pilgrimage a preference for integration. On July 23, 1909 wrote to the Hannens that he was an adherent of the Bahá'í Faith:

"It comes to me that I have never taken occasion to thank you specifically for all your kindness and patience, which finally culminated in my acceptance of the great truths of the Bahá'í Revelation. It has given me an entirely new conception of Christianity and of all religion, and with it my whole nature seems changed for the better...It is a sane and practical religion, which meets all the varying needs of life, and I hope I shall ever regard it as a priceless possession."

First actions

At this point, Gregory started organizing meetings for the religion as well, including one under the auspices of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, a Negro organization of which he was president previously.[13] He also wrote to `Abdu'l-Bahá, who responded to Gregory that he had high expectations of Gregory in the realm of race relations. The Hannens asked that Gregory attend some organizational meetings to help consult on opportunities for the Faith. With such meetings the practical aspects of integration with some Bahá'ís became crystallized while for others it became a strain they had to work to overcome.[8] Gregory received a letter in November 1909 from `Abdu'l-Bahá saying:

"I hope that thou mayest become… the means whereby the white and colored people shall close their eyes to racial differences and behold the reality of humanity, that is the universal truth which is the oneness of the kingdom of the human race…. Rely as much as thou canst on the True One, and be thou resigned to the Will of God, so that like unto a candle thou mayest be enkindled in the world of humanity and like unto a star thou mayest shine and gleam from the Horizon of Reality and become the cause of the guidance of both races."[8]

In 1910 Gregory stopped working as a lawyer and began a long period of service holding meetings and traveling for the religion and wrote and lectured on the subject of racial unity.[8][12] Some initial meetings were held in parallel among the races but `Abdu'l-Bahá made it known that the direction of the community was toward integrated meetings. The fact that upper class white Bahá'ís repeatedly achieved steps towards integration was a confirmation to Gregory of the power of the religion.[8] Gregory, still president of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, arranged for presentations by several Bahá'ís to the group.[14]

Gregory initiated a major trip through the South. He travelled to Richmond, Virginia, Durham, North Carolina and other locations in North Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, the city of his family and childhood, and Macon, Georgia where he told people about the religion.[12] In Charleston he is known to have presented talks at the Carpenter's Union Hall and made contact with a priest who had encountered the religion at Green Acre and met Mirzá `Abu'l-Fadl.[8] In Charleston an African American lawyer Alonzo Twine converted, the first Bahá'í of South Carolina, though Gregory's stay was short and he didn't return to Charleston for some years. In the meantime, unbeknownst to Gregory, Twine was committed to a mental institution by his mother and family priest and where he died a few years later - still handing out Bahá'í pamphlets he made himself.[8]

Gregory also began to participate more in the early Bahá'í administration. In February 1911 he was elected to the Washington's Working Committee of the Bahá'í Assembly, the first African-American to serve on that position.

Pilgrimage

On March 25, 1911, at the behest of `Abdu'l-Bahá, Gregory sailed from New York City through Europe to Egypt and Palestine to go on pilgrimage.[8][12] In Palestine, Gregory met with `Abdu'l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi and visited the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh and the Shrine of the Báb. After he had returned to Egypt from Palestine, the discussion of race unity in the United States came about with `Abdu'l-Bahá and the other pilgrims. `Abdu'l-Bahá stated that there was no distinction between the races, and then gave blackberries to each of the pilgrims, which Gregory interpreted as the symbolic sharing of black-coloured fruit. During this time, `Abdu'l-Bahá also started encouraging Gregory and Louisa Mathew, a white Englishwoman who was also a pilgrim, to get to know each other.

After leaving Egypt, Gregory travelled to Germany, before returning to the United States, where he spoke at a number of gatherings to Bahá'ís and their friends. When he returned to the United States he continued to travel mainly the southern United States talking about the Bahá'í Faith but elsewhere as well.[15] He held his first public meeting on the religion after his return to the States in February 1911[16] and published his own article in the Washington Bee in November being inspired by the action of `Abdu'l-Bahá in Britain,[17] when he was also first elected to a Washington Bahá'í working committee.[8]

1912

1912 was a momentous year for Gregory. In April he was elected to the national Bahá'í "executive board"[8] and assisted during `Abdu'l-Bahá's visit to the United States during which he repeatedly emphasized the oneness of humanity and used black-colored references for pictures of beauty and virtue.[8][12] See `Abdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West.

There are several prominent engagements where `Abdu'l-Bahá spoke thanks to the efforts of Gregory. The first was on 23 April 1912 when `Abdu'l-Bahá attended several events;[18] first he spoke at Howard University to over 1000 students, faculty, administrators and visitors — an event commemorated in 2009.[19] Then he attended a reception by the Persian Charg-de-Affairs and the Turkish Ambassador;[12] at this reception `Abdu'l-Bahá moved the place-names such that the only African-American present, Gregory, was seated at the head of the table next to himself.[12][20]

Then `Abdu'l-Bahá spoke at Bethel Literary and Historical Society where Gregory had a long history including being president.[12][21]

Later in June `Abdu'l-Bahá addressed the NAACP national convention in Chicago - and reported by W. E. B. Du Bois in The Crisis.[22]

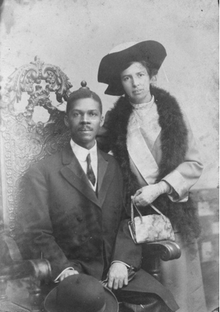

On September 27, 1912, Gregory and Louisa Mathew married becoming the first Bahá'í interracial couple.[12]

During his travels, whenever he was accompanied by his wife, they received a range of different reactions because interracial marriage was illegal or unrecognized in a majority of the states at that time.

Succeeding years of service

The struggle of the Washington Bahá'í community, where the Gregories lived, towards fully and only integrated meetings and institutions came about in Spring 1916.[8] That summer `Abdu'l-Bahá's earliest Tablets of the Divine Plan arrived. The Tablet for the South arrived to Joseph Hannen with whom Gregory worked on a committee. By December Gregory had traveled among 14 of the 16 southern states named mostly speaking to student audiences and began a second round in 1917. Complementing Gregory's priorities was the founding of NAACP organizations in South Carolina starting in 1918 though the KKK activities increased the pace of lynchings. Many of the initial organizers of the NAACP were personally known to Gregory.[8] In 1919 after the remaining letters of the `Abdu'l-Bahá arrived and used the example of St. Gregory the Illuminator as the model of effort in the spread of the religion. Hannen and Gregory were subsequently elected to a committee focused on the American South and Gregory focused on two approaches - presenting the religion's teachings on race issue to social leaders as well as to the general public - and initiated his next more extensive trip from 1919 to 1921 often with Roy Williams, an African-American Bahá'í from New York city. During 1920 a pilgrim returned from seeing `Abdu'l-Bahá with a focus on initiating conferences on race issues called "Race Amity Conferences" and Gregory consulted by letter on how to begin. The first one was held May 1921 in Washington DC.

Among the contacts in South Carolina Gregory made was Josiah Morse of the University of South Carolina.[8] As a result, several Bahá'ís speakers would be known at university based events starting in the 1930s. Gregory developed a friendship with Samuel Chiles Mitchell, president of the University of South Carolina (1909–1913), and shared that `Abdu'l-Bahá's views he heard at the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration affected him in his interracial work into the 1930s.[8] In addition to supportful connections there was also increasing opposition. Gregory's January 1921 appearance in Columbia SC registered African-American ministers who warned of his presence and the dangers of his religion though others positively invited Gregory to speak. One of the ministers who opposed him was the self-same minister who assisted in committing the first declared Bahá'í in South Carolina to an institution for the mentally insane.[8][23][24]

Gregory was then the first African-American to be elected to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada, a body which he would be elected to in 1922, 1924, 1927, 1932, 1934 and 1946. Correspondence and activities he carried on sometimes was carried in local newspapers in the US and beyond.[25]

In 1924 Gregory toured the country to a number of engagements and this tour he was able to be on stage with fellow African American Bahá'í and prominent thinker of the then developing Harlem Renaissance, Alain LeRoy Locke.[26]

On the personal side his father died in 1929 but Gregory heard his father's commendations for his work, marriage, and principles and was known to hand out pamphlets of the religion though he never officially converted.[8] At the funeral some thousand people came and Gregory read Bahá'í prayers.

In the 1930s Gregory would apply himself in intra- and international developments of the religion. In December 1931 he helped start a Bahá'í study class during a brief visit to Atlanta, and lived in Nashville a number of months helping inquirers from Fisk University who eventually helped found that city's first local Spiritual Assembly.[12] In response to Shoghi Effendi's call to the wide goals of the Tablets of the Divine Plan the United States community arranged a program of action and Gregory, this time with his wife, traveled to and lived in Haiti in 1934 promoting the religion though the Haitan government asked them to leave in a matter of months.[8] In 1940 the Atlanta Bahá'í community struggled over integrated meetings and Gregory was among those tasked with resolving the situation in favor of integrated meetings.[8] In early 1942 Gregory spoke at several black schools and colleges West Virginia, Virginia, and the Carolinas as well as serving as on the first "assembly development" committee especially focused on supporting materials for the growth of the religion in south and Central America. In 1944 Gregory was on the planning committee for the "All-America Convention" which was going to have attendees from all Bahá'í national communities north and south and wrote the convention report for the Bahá'í News national journal[27] and then traveled again starting the winter of 1944 through 1945 among five southern states.[8]

Talks of his and his work in Race Amity conventions organized by Bahá'ís would appear in a variety of newspapers from the 1920s through the 1950s.[28]

Later years

In December 1948 Gregory suffered a stroke returning from a funeral for a friend[8] and between him and his wife, whose health also declined, began to stay closer to home, now at Green Acre Bahá'í School in Eliot, Maine. Nevertheless, Gregory carried on correspondence with U.S. District Court Judge Julius Waties Waring and his wife in 1950-1 who was involved in Briggs v. Elliott.

Gregory died aged seventy-seven on July 30, 1951. He is buried at a cemetery near the Green Acre Bahá'í school. Significantly, his wife Louisa went for comfort with the Noisette family in New York after his passing.

On his death, Shoghi Effendi, then head of the religion, cabled to the American Bahá'í community::

"Profoundly deplore grievous loss of dearly beloved, noble-minded, golden-hearted Louis Gregory, pride and example to the Negro adherents of the Faith. Keenly feel loss of one so loved, admired and trusted by 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Deserves rank of first Hand of the Cause of his race. Rising Bahá'í generation in African continent will glory in his memory and emulate his example. Advise hold memorial gathering in Temple in token recognition of his unique position, outstanding services."[29]

This was Shoghi Effendi's first round of appointees as having achieved a distinguished rank in service to the religion named Hands of the Cause. Memorial observances of his death were among the first events of the newly arrived Bahá'ís and first converts in Uganda from which Enoch Olinga, the father of victories, would appear in just two years. Bahá'í radio station WLGI is named after Gregory: the Louis Gregory Institute.

Notes

- ↑ "Mr. Louis George Gregory House #49". DC Bahá'í Tour 2012. 2012. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ↑ Francone, Brian (Nov 12, 2007). "Service of family member makes history". Savannah Now. Savannah, Georgia. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ↑ "Law Class to Graduate; Arrangements being Completed for Howard University Commencement" (PDF). The Washington Times. May 22, 1902. p. 8 second column top. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Young Lawyers to Make Debut; Seventy-four will be admitted to practice before Supreme Court on Next Tuesday" (PDF). The Washington Times. October 4, 1902. p. 8 5th column top. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ J. Clay Smith, Jr. (1 January 1999). Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer, 1844-1944. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 133, 136. ISBN 0-8122-1685-7.

- ↑ "The Wizard Banqueted; Washington's Representative Citizens Greet the Taskegeean at the Festive Board…". The Colored American. March 26, 1904. pp. 12–13 (listed on page 13, 1st column towards bottom). Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Doings of Clubs in the District; Howard Alumni Officers" (PDF). The Washington Times. October 21, 1906. pp. 5, 7th column near top. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Venters, Louis E., the III (2010). Most great reconstruction: The Baha'i faith in Jim Crow South Carolina, 1898-1965 (Thesis). Colleges of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-243-74175-2. UMI Number: 3402846.

- ↑ "Bethel Literary and Historical Association; Officers" (PDF). The Washington Bee. December 21, 1907. pp. 4, 3rd column middle. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ "The Week in Society; Bethel Literary" (PDF). The Washington Bee. November 6, 1909. pp. 5, 2nd column bottom and third column top. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ "No Negro Wanted" (PDF). The Washington Bee. March 9, 1907. pp. 5, 5th column top. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Morrison, Gayle (1982). To move the world : Louis G. Gregory and the advancement of racial unity in America. Wilmette, Ill: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-188-4.

- ↑ Thomas, Richard Walter (2006). Lights of the spirit: historical portraits of Black Bahá'ís in North America. US Baha'i Publishing Trust. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-1-931847-26-1.

- ↑ "Bethel Literary" (PDF). The Washington Bee. April 9, 1910. p. 8 2nd and 3rd column bottom. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Mr. Louis G. Gregory...". The Appeal. Saint Paul, MN, USA. 17 June 1911. p. 2 (5th col, down from top). Retrieved Oct 12, 2013.

- ↑ "The Week in Society (a talk; "A view of the heavens")" (PDF). The Washington Bee. February 11, 1911. p. 5 (1st column bottom, 2nd column top). Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ Gregory, Louis George (November 11, 1911). "Bahai Revelation - In Relation to Christianity and Other Religion; Scope, History and Prescepts" (PDF). The Washington Bee. p. 1 (1st column top into 2nd). Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ Parsons, Agnes (1996). Hollinger, Richard, ed. `Abdu'l-Bahá in America; Agnes Parsons' Diary. US: Kalimat Press. pp. 23–26, 31–34. ISBN 978-0-933770-91-1.

- ↑ Musta, Lex (25 March 2009). "Get on the Bus for a Spiritual Journey through DC and Baha'i History". The News. Bahai Faith, Washington DC. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ↑ Dr. Ward, Allan L. (1979). 239 Days; `Abdu'-Bahá's Journey in America. US Bahá'í Publishing Trust. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-87743-129-9.

- ↑ "Bahai Leader May Address Bethel Literary". Washington Bee. 30 March 1912. pp. 2, 4th column. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ↑ `Abdu'l-Bahá (4 June 1912). Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt; MacLean, M. D., eds. "The Brotherbood of Man". The Crisis; A Record of the Darker Races. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. 04 (2): 49–52. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ↑ Lowery, Rev. L. E. (February 19, 1921). "Rev. L. E. Lowery's Column; The Bahai Movement". The Southern indicator. Columbia, SC, USA. p. 6 (3rd col, top). Retrieved Oct 12, 2013.

- ↑ Chandler, Rev. C. W. (18 March 1944). "He Hath Made of One Blood All The Nations". Auckland Star. Auckland, New Zealand. p. 4. Retrieved Oct 12, 2013.

- ↑ "The Bahai Movement". The Dallas Express. Denton, TX, USA. January 3, 1920. p. 9 (3rd col, down from top). Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Convention for Amity meeting at Big Local …". The Pittsburgh Courier. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. 1 November 1924. p. 10. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ "The historic thirty-sixth convention". Bahá'í News (170): 1–8. September 1944.

- ↑

- "Religious group plan convention". The Times. San Mateo, California. 27 April 1926. p. 6. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- "Comments by The Age editors on sayings of other editors". The New York Age. New York, New York. 23 July 1927. p. 4. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- "Conference will open here on August 21". The Portsmouth Herald. Portsmouth, New Hampshire. 19 August 1930. p. 10. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- "Howard University, (talks by Gregorys)". The New York Age. New York, New York. 31 October 1931. p. 10. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- . Rogers, J. A (2 December 1950). "Your History". The Pittsburgh Courier. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. p. 7. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi (collected letters from 1947–57). Citadel of Faith. Haifa, Palestine: US Bahá'í Publishing Trust, 1980 third printing. p. 163. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

Further reading

- Venters, Louis E., the III (2010). Most great reconstruction: The Baha'i faith in Jim Crow South Carolina, 1898-1965 (Thesis). Colleges of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-243-74175-2. UMI Number: 3402846.

- The National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of the United States (2006-06-28). "Selected profiles of African-American Baha'is". bahai.us. Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- Louis Gregory Museum (2003). "About Louis G. Gregory". louisgregorymuseum.org. Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- African American History Online (January 2005). "Louis George Gregory's Appearance in State African American History Calendar of South Carolina in 2005". scafricanamericanhistory.com. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- Morrison, Gayle (2009). "Gregory, Louis George (1874-1951)". Bahá'í Encyclopedia Project. Evanston, IL: National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the United States.

- Morrison, Gayle (1982). To move the world : Louis G. Gregory and the advancement of racial unity in America. Wilmette, Ill: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-188-4.

- Musta, Leonard (2014). Personal Research Notes on Louis George Gregory from 1996-2014. Crofton, MD: Unpublished.

External links

- Louis Gregory Museum

- The Louis Gregory Project

- Louis Gregory at Find A Grave

- Mr. Gregory's resting place, Eliot, ME