London and Brighton Railway

The London and Brighton Railway (L&BR) was a railway company in England which was incorporated in 1837 and survived until 1846. Its railway runs from a junction with the London & Croydon Railway (L&CR) at Norwood - which gives it access from London Bridge, just south of the River Thames in central London. It runs from Norwood to the South Coast at Brighton, together with a branch to Shoreham-by-Sea.

Background

During the English Regency, and particularly after the Napoleonic Wars, Brighton rapidly became a fashionable social resort, with more than 100,000 passengers being carried there each year by coach.[1]

Early schemes

A proposal by William James in 1823 for the construction of a London to Brighton tramway, using the track bed of the Surrey Iron Railway between Wandsworth and Croydon, was largely ignored.[2] However, about 1825 a company called The Surrey, Sussex, Hants, Wilts & Somerset Railway employed John Rennie to survey a route to Brighton, but again the proposal came to nothing.[3]

In 1829 Rennie was commissioned to survey two possible railway routes to Brighton. The first of these, via Dorking and Horsham and Shoreham was undertaken for him by Charles Blacker Vignoles, the other more direct route, via Croydon Redhill and Haywards Heath, was by Rennie himself.[4] This latter route would have started at Kennington Park. However both of these schemes were abandoned due to lack of support in Parliament.

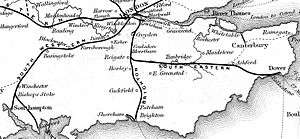

These schemes were revived in 1835, which generated further proposals so that by 1836 there were six possible routes under consideration.[5] These were:

- Rennie's direct route via Redhill and Haywards Heath but amended to make use of the London and Croydon Railway from London Bridge

- Henry Robinson Palmer's via Woldingham, Oxted and Lindfield (with a proposed link to Dover).

- Joseph Gibbs's from London Bridge via Croydon

- Nicholas Wilcox Cundy's from Nine Elms, via Mitcham Leatherhead, Dorking, Horsham and Shoreham.

- Charles Vignoles' from Elephant and Castle via Croydon, Merstham and Horsham.

- Robert Stephenson's from the London and Southampton Railway at Wimbledon, then via Epsom, Mickleham, Dorking, Horsham and Shoreham.

Eventually it became a battle between the supporters of Rennie's direct route (which was the most difficult and expensive to build), and Stephenson's (which was longer but involved less civil engineering work). After prolonged campaigns by the supporters of the different proposals, a bill for Stephenson's route was approved by the House of Commons in 1836, but was later rejected by the House of Lords. A Parliamentary Committee of Enquiry was established to consider the merits of the schemes which commissioned a report by nder Captain Robert Alderson. He recommended the adoption of the Rennie direct route after Redhill. However, members of the Committee insisted that a stretch of the new route between Croydon and Redhill should be shared with the South Eastern Railway as part of its projected route to Dover, which had not been part of Rennie's plan.[6]

The final agreed route therefore consisted of a new line from a junction with the London and Croydon Railway (then under construction) at Norwood to Brighton with additional branches to Lewes and Shoreham. An Act for the construction of the line was passed in July 1837, with an authorised capital of £2.4 million.[7] The new company was also permitted to buy the track of the Croydon, Merstham and Godstone Iron Railway. The expenditure associated with the Parliamentary contest in choosing the route was estimated to be more than £193,000.[8]

Construction

The London and Croydon Railway line ran from London Bridge to West Croydon and was opened in 1839. The engineer for the Brighton extension was John Urpeth Rastrick, who began construction of the 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm)[9] line in 1838. By July 1840, 6206 men, 962 horses, five locomotives and seven stationary engines were employed.[10]

The new main line included substantial earthworks and five tunnels through the North Downs at Merstham, the Wealden ridge near Balcombe and at Haywards Heath, and the South Downs at Patcham and Clayton. The railway also had a 1,475 ft (449.6 m) long, 96 ft (29.3 m) high viaduct over the river Ouse near Balcombe.

The Brighton - Shoreham branch was completed in May 1840, before the main line, as there were no significant civil engineering works on this section. Locomotives and rolling stock had to be transhipped by road for what was, in the first year, an isolated stretch of railway.

The main line was opened in two sections, since major earthworks delayed completion in one piece. The Norwood Junction - Haywards Heath section was opened on 12 July 1841 and the remainder of the line from Haywards Heath to Brighton on 21 September 1841.

The branch line to Lewes authorised by the 1837 act was built 1844-46 by a separate company, the Brighton Lewes and Hastings Railway.

Architecture

The railway employed the architect David Mocatta, who designed a number of attractive yet practical Italianate style stations using standardised modules. These were London Bridge, Croydon, Godstone Road, Red Hill and Reigate Road, Horley, Crawley, Haywards Heath, Hassocks Gate, and Brighton. Only Mocatta's station at Brighton is still standing (which also incorporated the railway offices), but his building is now largely obscured by later additions.[11] Mocatta also designed the eight stone and brick pavilions and a stone balustrade which embellish Rastrick's brick viaduct over the river Ouse.

The L&BR built fully equipped locomotive depots and workshops at Brighton in 1840 and Horley in 1841. Horley was originally intended to serve as the principal workshop of the railway, but John Chester Craven decided in 1847 to develop Brighton railway works instead.[12]

Locomotives

The L&BR acquired 34 steam locomotives between January 1839 and March 1843, the first two of which were a 2-2-2 and an 0-4-2 supplied by Jones, Turner and Evans and used by the contractors constructing the line. The remainder were mainly 2-2-2 consisting of 16 supplied by Sharp, Roberts and Company, six by Edward Bury and Company, four by William Fairbairn, and three by G. and J. Rennie. The last three locomotives were 2-4-0 supplied by George Forrester and Company between October 1842 and March 1843. For details see List of early locomotives of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway.

Initially these locomotives were the responsibility of the civil engineer and his assistant, but this arrangement was ended after an unfavourable report on their safety in 1843. From 1842 the L&CR had pooled its locomotive stock with the South Eastern Railway(SER), to form the 'Croydon and Dover Joint Committee'. From March 1844 the L&BR joined the scheme and their locomotives were operated by the 'Brighton, Croydon and Dover Joint Committee', which also ordered further locomotives. These pooling arrangements had the advantage of providing the L&BR with access to the South Eastern Railway repair facilities, at New Cross but caused great operating problems. In March 1845 John Gray was appointed as Locomotive Superintendent of the L&BR and in April the company gave notice of withdrawal from the arrangement from January 1846, when the pooled locomotives were divided between the companies.[13]

Following the dispersal of the pool in March 1845, the L&BR acquired 44 locomotives, some of which it had previously owned, and the remainder from the SER, L&CR, or else those purchased by the Joint Committee. For details see List of early locomotives of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway.

Amalgamation

On 27 July 1846, the L&B amalgamated with the L&C, the Brighton and Chichester Railway and the Brighton Lewes and Hastings Railway to form the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway. The amalgamation had been brought about by shareholders in the L&CR and L&BR who were dissatisfied with the early returns from their investment.[14]

References

- ↑ Bradley, (1969)

- ↑ James, William (1823). Report, or essay, to illustrate the advantages of direct inland communication through Kent, Surrey, Sussex, and Hants: to connect the metropolis with the ports of Shoreham, (Brighton), Rochester, (Chatham) and Portsmouth, by a line of engine rail-road. London: J. and A. Arch.

- ↑ Dendy Marshall, C. F.; Kidner, R.W. (1963). A history of the Southern Railway. London: Ian Allan. pp. 193–4. OCLC 315039503.

- ↑ Gordon, William John (1910), Our home railways, 1, London and New York: Frederick Warne & Co., p. 142

- ↑ Gordon, William John (1910), Our home railways, 1, London and New York: Frederick Warne & Co., p. 143

- ↑ Gordon, p.146, Turner (1077), pp.113-4.

- ↑ Whishaw, Francis (1842). The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland. London: John Weale. p. 269. ISBN 0-7153-4786-1.

- ↑ Whishaw, p.270.

- ↑ William Templeton - The Locomotive Engine Popularly Explained - Page 96

- ↑ Bradley (1969) p.4.

- ↑ Turner (1977) p. 128.

- ↑ Griffiths (1999) p. 79.

- ↑ Bradley, D.L. (1963). Locomotives of the south Eastern Railway. Solihull: Railway Correspondence and Travel Society. pp. 13–16.

- ↑ Turner, John Howard (1977). The London Brighton and South Coast Railway 1 Origins and Formation. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-0275-X. p.253-71.

Sources

- Bradley, D.L. (1969). Locomotives of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway: Part 1. Railway Correspondence and Travel Society.

- Cooper, B. K., Rail Centres: Brighton, Booklaw Publications, 1981. ISBN 1-901945-11-1

- Gray, Adrian, The London to Brighton Line 1841-1977, The Oakwood Press, 1977. [no ISBN]

- Searle, Muriel V., Down the line to Brighton, Baton Transport, 1986. ISBN 0-85936-239-6

- Turner, John Howard, The London Brighton and South Coast Railway: 1 Origins and Formation, Batsford, 1977. ISBN 0-7134-0275-X

External links

- March 1843 timetable from Bradshaw's Railway Monthly (XVI)