List of National Treasures of Japan (crafts: swords)

The term "National Treasure" has been used in Japan to denote cultural properties since 1897,[1][2] although the definition and the criteria have changed since the introduction of the term. The swords and sword mountings in the list adhere to the current definition, and have been designated national treasures according to the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties that came into effect on June 9, 1951. The items are selected by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology based on their "especially high historical or artistic value".[3][4] The list presents 110 swords and 12 sword mountings from ancient to feudal Japan, spanning from the late Kofun to the Muromachi period. The objects are housed in Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, museums or held privately. The Tokyo National Museum houses the largest number of these national treasures, with 20 of the 122.[4]

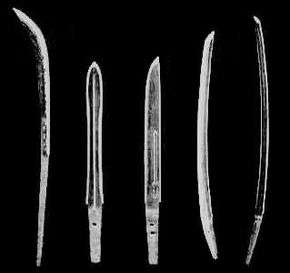

During the Yayoi period from about 300 BC to 300 AD, iron tools and weapons such as knives, axes, swords or spears, were introduced to Japan from China via the Korean peninsula.[5][6][7][8] Shortly after this event, Chinese, Korean, and eventually Japanese swordsmiths produced ironwork locally.[9][10] Swords were forged to imitate Chinese blades:[11] generally straight chokutō with faulty tempering. Worn slung from the waist, they were likely used as stabbing and slashing weapons.[11][12] Although functionally it would generally be more accurate to define them as hacking rather than slashing weapons. Swordmaking centers developed in Yamato, San'in and Mutsu where various types of blades such as tsurugi, tōsu and tachi[nb 1] were produced.[11][13] Flat double-edged (hira-zukuri) blades originated in the Kofun period, and around the mid-Kofun period swords evolved from thrusting to cutting weapons.[13][13] Ancient swords were also religious objects according to the 8th century chronicles Nihon Shoki and Kojiki. In fact, one of the Imperial Regalia of Japan is a sword, and swords have been discovered in ancient tumuli or handed down as treasures of Shinto shrines or Buddhist temples.[9][13] Few ancient blades (jokotō) exist because the iron has been corroded by humidity.[8][13][14]

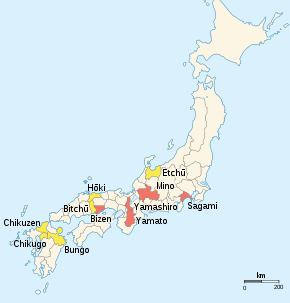

The transition from straight jokotō or chokutō to deliberately curved, and much more refined Japanese swords (nihontō), occurred gradually over a long period of time, although few extant swords from the transition period exist.[15] Dating to the 8th century, Shōsōin swords and the Kogarasu Maru show a deliberately produced curve.[16] Yasutsuna from Hōki Province forged curved swords that are considered to be of excellent quality. Stylistic change since then is minimal, and his works are considered the beginning of the old sword (kotō) period, which existed until 1596, and produced the best-known Japanese swordsmiths.[17] According to sources Yasutsuna may have lived in the Daidō era (806–809), around 900; or more likely, was a contemporary of Sanjō Munechika and active in the Eien era (987, 988).[13][15][18] The change in blade shape increased with the introduction of horses (after 941) into the battlefield, from which sweeping cutting strokes with curved swords were more effective than stabbing lunges required of foot soldiers.[9][16][18][19] Imparting a deliberate curve is a technological challenge requiring the reversal of natural bending that occurred when the sword edge is hammered. The development of a ridge (shinogi) along the blade was essential for construction.[20] Various military conflicts during the Heian period helped to perfect the techniques of swordsmanship, and led to the establishment of swordsmiths around the country.[19] They settled in locations close to administrative centers, where the demand for swords was high, and in areas with easy access to ore, charcoal and water.[17] Originally smiths did not belong to any school or tradition.[21] Around the mid to late-Heian period distinct styles of workmanship developed in certain regional centers.[22] The best known of these schools or traditions are the gokaden (five traditions) with each producing a distinct style of workmanship and associated with the five provinces: Yamashiro, Yamato, Bizen, Sagami/Sōshū and Mino. These five schools produced about 80% of all kotō period swords.[17][21][23] Each school consisted of several branches.[17] In the late Heian period Emperor Go-Toba, a sword lover, summoned swordsmiths from the Awataguchi school of Yamashiro, the Ichimonji school of Bizen and the Aoe school of Bitchū Province to forge swords at his palace. These smiths, known as goban kaji (honorable rotation smiths) are considered to have been the finest swordsmiths of their time.[nb 2][21][24] Go-Toba selected from the Awataguchi, Hisakuni and Ichimonji Nobufusa to collaborate on his own tempering.[25] Early Kamakura period tachi had an elaborately finished tang and an elegant dignified overall shape (sugata).[21] Tantō daggers from the same period showed a slight outward curvature.[24]

Around the mid-Kamakura period, the warrior class reached its peak of prosperity.[26] Consequently, sword production was thriving in many parts of Japan.[26] Following the Mongol invasions of 1274 and 1281, smiths aimed at producing stronger swords that would pierce the heavy armour of the invaders. To achieve this, tachi became wider, thicker with an overall grand appearance (sugata) and a straight temper line.[26][27] With the Mongol threat dissipated at the end of the Kamakura period, this trend was partially reversed, as blades grew longer with a more dignified shape than those from the mid-Kamakura period.[27] However the so-called "unchangeable smiths", including Rai Kunitoshi, Rai Kunimitsu, Osafune Nagamitsu and Osafune Kagemitsu, continued to produce swords of the elegant style of the late Heian/early Kamakura period. These swords were particularly popular with Kyoto's aristocracy.[27] The production of tantō daggers increased considerably towards the late Kamakura period.[28] Master tantō makers include Awataguchi Yoshimitsu, Rai Kunitoshi, Shintōgo Kunimitsu, Osafune Kagemitsu, Etchū Norishige and Samonji.[28] The naginata appeared as a new weapon in the late Kamakura period.[28] The confrontation between the Northern and Southern Court resulted in a 60-year-long power struggle between warrior lords known as the Nanboku-chō period and caused a tremendous demand for swords.[29] The stylistic trends of the Kamakura period continued, and tachi were characterized by magnificent shape, growing in overall length and the length of the point (kissaki). They were generally wide and disproportionately thin.[29] Similarly tantō grew in size to 30–43 cm (12–17 in) and became known as ko-wakizashi or sunnobi tantō (extended knives).[30] But also tantō shorter than those of the Kamakura period were being forged.[30] Enormous tachi called seoi-tachi (shouldering swords), nodachi (field swords) and ōdachi with blades 120–150 cm (47–59 in) long were forged.[nb 3][31] The high demand for swords during feudal civil wars after 1467 (Sengoku period) resulted in mass production and low quality swords as swordsmiths no longer refined their own steel.[32] There are no national treasure swords after this period.

Statistics

| Prefecture | City | National Treasures |

|---|---|---|

| Aichi | Nagoya | 8 |

| Ehime | Imabari | 3 |

| Fukuoka | Dazaifu | 1 |

| Fukuoka | 2 | |

| Yanagawa | 1 | |

| Gifu | Takayama | 1 |

| Hiroshima | Hatsukaichi | 2 |

| Private | 5 | |

| Hyōgo | Nishinomiya | 2 |

| Ibaraki | Kashima | 1 |

| Tsuchiura | 1 | |

| Ishikawa | Kanazawa | 1 |

| Kagoshima | Kagoshima | 1 |

| Kanagawa | Kamakura | 1 |

| Kōchi | Hidaka | 1 |

| Kyoto | Kyoto | 2 |

| Nara | Nara | 6 |

| Okayama | Okayama | 3 |

| Private | 1 | |

| Osaka | Kawachinagano | 1 |

| Osaka | 3 | |

| Private | 9 | |

| Saitama | Saitama | 2 |

| Shizuoka | Numazu | 1 |

| Mishima | 1 | |

| Private | 2 | |

| Shizuoka | 1 | |

| Tochigi | Nikkō | 4 |

| Tokyo | Private | 12 |

| Tokyo | 39 | |

| Yamagata | Tsuruoka | 2 |

| Yamaguchi | Hōfu | 1 |

| Iwakuni | 1 |

| Period | National Treasures |

|---|---|

| Kofun period | 1 |

| Asuka period | 2 |

| Heian period | 19 |

| Kamakura period | 86 |

| Nanboku-chō period | 13 |

| Muromachi period | 1 |

.png)

Usage

The table's columns (except for Remarks and Design and material) are sortable pressing the arrows symbols. The following gives an overview of what is included in the table and how the sorting works. Not all tables have all of the following columns.

- Type/Name: type of sword or sword mounting; blades mentioned in the kyōhō era Kyōhō Meibutsuchō as masterpieces (meibutsu) are mentioned by name and marked in yellow

- Signature: for signed swords, the signature and its reading; otherwise "unsigned"

- Swordsmith: name of the swordsmith who forged the blade; if applicable it includes the name of the school; the ten students of Masamune (juttetsu) are marked in green; the goban kaji, smiths summoned to the court of Emperor Go-Toba are marked in blue

- Remarks: additional information such as notable owners or its curvature

- Date: period and year; the column entries sort by year. If the entry can only be dated to a time-period, they sort by the start year of that period

- Length: distance from the notch to the tip of the sword

- Present location: "temple/museum/shrine-name town-name prefecture-name"; column entries sort as "prefecture-name town-name temple/museum/shrine-name"

The table of sword mountings differentiates between Sword type and Mounting type; includes a column on the employed Design and material; and lists the Overall length as the mounting in addition to the sword's length.

- Key

| # | Meibutsu |

| * | One of the ten students of Masamune |

| ^ | One of the goban kaji |

Treasures

Ancient swords (jokotō)

Four ancient straight swords (chokutō) and one tsurugi handed down in possession of temples and shrines have been designated as National Treasure craft items.[nb 4] A notable collection of 55 swords and other weapons from the 8th century have been preserved in the Shōsōin collection. Being under the supervision of the Imperial Household Agency, neither these items nor the well known Kogarasu Maru are National Treasures.[33][34]

| Gilt bronze tachi with ring pommel (金銅荘環頭大刀拵 kondōsō kantō tachi goshirae)[14][35][36] | Double-edged blade, said to be the oldest Japanese object transmitted from generation to generation; offered to Kunitokotachi by the Kusakabe clan and worshipped as shintai of Omura Shrine; 527 g (18.6 oz), hilt length: 7.5 cm (3.0 in), scabbard length: 92.1 cm (36.3 in) | late Kofun period | Chokutō | 68.4 cm (26.9 in) | Omura Shrine,[nb 5] Hidaka, Kōchi |

| Great Bear sword (七星剣 Shichiseiken) or Seven Stars Sword[37] | The sword contains a gold inlay of clouds and seven stars forming the Great Bear constellation. According to a document at Shitennō-ji, this sword was owned by Prince Shōtoku. Considered to be directly imported from the Asian continent | Asuka period, 7th century | Chokutō | 62.1 cm (24.4 in) | Shitennō-ji, Osaka |

| Heishi Shōrin ken (丙子椒林剣)[14][37] | The sword contains an inscription in gold inlay: Heishi shōrin (丙子椒林) which according to one theory, represents 丙子 (bǐng-zǐ), which is a stem-branch of the Sexagenary cycle and the author's name: Shōrin (椒林). According to a document at Shitennō-ji, this sword was owned by Prince Shōtoku. Considered to be directly imported from the Asian continent | Asuka period | Chokutō | 65.8 cm (25.9 in) | Shitennō-ji, Osaka |

| Chokutō (or futsu-no mitama no tsurugi (布都御魂剣)) and black lacquer mounting (黒漆平文大刀拵 kuro urushi hyōmontachi goshirae)[nb 6][14][38] | Legendary sword used by Emperor Jimmu to found the Japanese nation | early Heian period | Chokutō | 223.5 cm (88.0 in) | Kashima Shrine, Kashima, Ibaraki, Ibaraki |

| Unsigned sword (剣 無銘 tsurugi mumei)[nb 7][39][40][41] | Handle in the shape of a Buddhist ritual implement, a pestle like weapon with three prongs (sanko); double-edged sword for ceremonial use only | early Heian period | Tsurugi | 62.2 cm (24.5 in) | Kongō-ji (金剛寺), Kawachinagano, Osaka |

Old swords (kotō)

105 swords from the kotō period (late 10th century to 1596) including tachi (61), tantō (26), katana (11), ōdachi (3), naginata (2), tsurugi (1) and kodachi (1) have been designated as national treasures. They represent works of four of the five traditions: Yamato (5), Yamashiro (19), Sōshū (19), Bizen (45); and blades from Etchū Province (3), Bitchū Province (5), Hōki Province (2) and Saikaidō (7).

Yamato Province

The Yamato tradition is the oldest, originating as early as the 4th century with the introduction of ironworking techniques from the mainland.[42] According to legend, the smith Amakuni forged the first single-edged long swords with curvature (tachi) around 700.[43] Even though there is no authentication of this event or date, the earliest Japanese swords were probably forged in Yamato Province.[44] During the Nara period, many good smiths were located around the capital in Nara. They moved to Kyoto when it became capital at the beginning of the Heian period, but about 1200 smiths gathered again in Nara when the various sects centered in Nara rose to power during the Kamakura period and needed weapons to arm their monks. Thus, the Yamato tradition is associated closely with the warrior monks of Nara.[45][46] Yamato tradition sugata[j 1] is characterized by a deep torii-zori,[j 2] high shinogi,[j 3] and slightly extended kissaki.[j 4] The jihada[j 5] is mostly masame-hada,[j 6] and the hamon[j 7] is suguha,[j 8] with rough nie.[j 9] The bōshi[j 10] is mainly ko-maru.[j 11][23][47] Generally the style of Yamato blades is considered to be restrained, conservative and static.[46] Five major schools or branches of the Yamato tradition are distinguished: Senjuin,[nb 8] Shikkake, Taima,[nb 9] Tegai[nb 10] and Hōshō.[nb 11] Four of the five schools are represented by national treasure swords.[45][48]

| Tachi[49] | Kuniyuki (国行) | Taima Kuniyuki (当麻国行) | Sword by the founder of the Taima branch; handed down in the Abe clan; curvature: 1.5 cm (0.59 in) | Kamakura period, around Shōō era (1288–1293) | 69.7 cm (27.4 in) | The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords (日本美術刀剣保存協会 Zaidanhōjin Nippon Bijutsu Tōkenhozonkyōkai), Tokyo |

| Tachi[49] | Nobuyoshi (延吉) | Senjuin Nobuyoshi (千手院延吉) | Formerly the property of Emperor Go-Mizunoo, curvature: 2.8 cm (1.1 in) | Kamakura period, around Bunpō era (1317–1319) | 73.5 cm (28.9 in) | The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords (日本美術刀剣保存協会 Zaidanhōjin Nippon Bijutsu Tōkenhozonkyōkai), Tokyo |

| Tachi[50] | Kanenaga (包永) | Tegai Kanenaga (手掻包永) | Sword by the founder of the Tegai branch | Kamakura period, around Shōō era (1288–1293) | 71.2 cm (28.0 in) | Seikadō Bunko (静嘉堂文庫), Tokyo |

| Ōdachi | year five of the Jōji era (1366), 43rd year of the sexaganary cycle (year of the fire horse), Senjuin Nagayoshi (貞治五年丙午千手院長吉 jōjigonen hinoeuma Senjuin Nagayoshi) | Senjuin Nagayoshi (千手院長吉) | Curvature: 4.9 cm (1.9 in) | Nanboku-chō period, 1366 | 136 cm (54 in) | Ōyamazumi Shrine, Imabari, Ehime |

| Tantō or Kuwayama Hōshō (桑山保昌)#[51] | Takaichi ? ... Sadayoshi (高市□住金吾藤貞吉 Takaichi ? jū kingo fuji Sadayoshi), ?kyō yonen jūgatsu jūhachinichi (□亨〈二二〉年十月十八日) | Hōshō Sadayoshi (保昌貞吉) | — |

Kamakura period, around Bunpō era (1317–1319) | — |

Private (Matsumoto Ko), Osaka |

Yamashiro Province

The Yamashiro tradition was centered around the capital Kyoto in Yamashiro Province where swords were in high demand. Sanjō Munechika (c. 987) was a forerunner of this tradition, and the earliest identified smith working in Kyoto.[52] Various branches of the Yamashiro tradition are distinguished: Sanjō, Awataguchi, Rai, Ayanokoji, Nobukuni, Hasebe and Heian-jo.[53]

Yamashiro tradition sugata is characterized by torii-zori, smaller mihaba,[j 12] slightly bigger kasane,[j 13] funbari,[j 14] and small kissaki. The jihada is dense small-grained itame-hada[j 15] and the hamon is suguha in nie, or small-grain nie.[23]

Sanjō, Ayanokoji and Hasebe schools

The Sanjō branch, named after a street in Kyoto and founded by Sanjō Munechika around 1000, is the oldest school in Yamashiro Province.[54] In the early Kamakura period it was the most advanced school of swordsmanship in Japan.[22] Sanjō Munechika's pieces, together with those of Yasutsuna from Hōki Province, consist of some of the oldest curved Japanese swords and mark the start of the old sword (kotō) period.[53] Sanjō school's sugata is characterized by a much narrower upper area compared to the bottom, small kissaki, torii-zori and deep koshi-zori.[j 16] The jihada uses good quality steel with abundant ji-nie[j 17] and chikei,[j 18] small mokume-hada[j 19] mixed with wavy, large hada. The hamon is bright and covered with thick nioi.[j 20] It is based on suguha mixed with small chōji midare.[j 21] Hataraki[j 22] appear along the temper line.[54]

The Ayanokoji school is named for a street in Kyoto where the smith Sadatoshi lived, and may possibly be a branch of the Sanjō school.[44][55] Ayanokoji tachi are slender with small kissaki. The jihada uses soft jigane,[j 23] small mokume-hada mixed with masame-hada, abundant ji-nie, yubashiri[j 24] and chikei. The temper line is small chōji midare, nie with lots of activity.[j 22][55]

A later branch of the Yamashiro tradition, was the Hasebe school which was active in the Nanboku-chō period and early Muromachi period.[56] It was founded by Hasebe Kunishige who originally came from Yamato Province. He travelled to Sagami Province where he became one of the ten great students of Masamune (Masamune juttetsu), and eventually went to Kyoto to found the Hasebe school.[56][57] The sugata is characterized by a wide mihaba, thin kasane and shallow sori.[j 25] The jihada is fine itame-hada mixed with masame-hada, chikei and abundant ji-nie. The hamon is of irregular width, narrow and small-patterned at the bottom and wide and large-patterned at the top of the blade. There are many tobiyaki[j 26] and hitatsura[j 27] as well as rough nie.[56]

| Tachi or Crescent Moon Munechika (三日月宗近 mikazuki munechika)#[28][58] | Sanjō (三条) | Sanjō Munechika (三条宗近) | One of the Five Swords under Heaven (天下五剣); the name, "crescent moon" refers to the shape of the tempering pattern; owned by Kōdai-in, wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi who bequeathed it to Tokugawa Hidetada, then handed down in the Tokugawa clan; curvature: 2.7 cm (1.1 in) | Heian period, 10th–11th century | 80 cm (31 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[59][60] | Sadatoshi (定利) | Ayanokoji Sadatoshi (綾小路定利) | Sword by the founder of the Ayanokoji school; handed down in the Abe clan from 1663 when Tokugawa Ietsuna gave it to Abe Masakuni, lord of Iwatsuki castle; strong curvature 3.0 cm (1.2 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century | 78.8 cm (31.0 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Katana or The Forceful Cutter (へし切 Heshi-kiri)#[61] | Unsigned | Hasebe Kunishige (長谷部国重)* | Owned by the Kuroda family, with an inscription in gold inlay by Honami Kotoku (本阿弥光徳): Hasebe Kunishige Honami ("長谷部国重本阿(花押)"), curvature 0.9 cm (0.35 in) | Nanboku-chō period, 14th century | 64.8 cm (25.5 in) | Fukuoka City Museum, Fukuoka, Fukuoka |

Awataguchi school

Located in the Awataguchi district of Kyoto, the Awataguchi school was active in the early and mid-Kamakura period.[52][62] Leading members of the school were Kunitomo, whose tachi are similar to those of Sanjō Munechika, and Tōshirō Yoshimitsu, one of the most celebrated of all Japanese smiths.[52] Yoshimitsu was the last of the significant smiths in the Awataguchi school, and the school was eventually replaced by the Rai school as the foremost school in Yamashiro Province.[62]

Characteristic for this school are engraved gomabashi[j 28] near the back ridge (mune), a long and slender tang (nakago), and the use of two-character signatures.[62] Awataguchi sugata is in the early Kamakura period similar to that of the Sanjō school; later in the mid-Kamakura period it became ikubi kissaki[j 29] with a wide mihaba. Tantō were normal sized with slight uchi-zori.[j 30][23] The jihada is nashiji-hada[j 31] of finest quality, dense small grain mokume-hada mixed with chikei, yubashiri appear, thick nie all over the ji[j 32] The hamon is narrow, suguha mixed with small chōji midare.[23][62]

| Tantō or Atsushi Tōshirō (厚藤四郎)#[63][64] | Yoshimitsu (吉光) | Tōshirō Yoshimitsu (藤四郎吉光) | Name ("atsushi" meaning "thick") refers to the unusual thickness of the blade; handed down through shoguns of the Ashikaga clan and in the possession of among others Toyotomi Hidetsugu, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Mōri Terumoto; presented to Tokugawa Ieyasu by the Mōri family | Kamakura period, 13th century | 21.8 cm (8.6 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tantō or Gotō Tōshirō (後藤藤四郎)#[65] | Yoshimitsu (吉光) | Tōshirō Yoshimitsu (藤四郎吉光) | Formerly in the possession of the Gotō house | Kamakura period, 13th century | 27.6 cm (10.9 in) | Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya, Aichi |

| Tantō[66] | Yoshimitsu (吉光) | Tōshirō Yoshimitsu (藤四郎吉光) | Formerly in the possession of the Tachibanaya family | Kamakura period | 23.2 cm (9.1 in) | Ohana Museum, Yanagawa, Fukuoka |

| Ken[67] | Yoshimitsu (吉光) | Tōshirō Yoshimitsu (藤四郎吉光) | The blade was part of the dowry of the adopted daughter (Seitaiin) of Tokugawa Iemitsu on her wedding with Maeda Mitsutaka; one year after Seitaiin's death, her son, Maeda Tsunanori offered the blade to the Shirayamahime Shrine praying for her happiness in the next life; width: 2.2 cm (0.87 in) | Kamakura period | 22.9 cm (9.0 in) | custodian: Ishikawa Prefecture Art Museum, Kanazawa (owner: Shirayamahime Shrine (白山比咩神社 Shirayamahime-jinja), Hakusan), Ishikawa |

| Tachi[68] | Hisakuni (久国) | Hisakuni (久国) | Curvature: 3 cm (1.2 in), breadth at butt: 2.7 cm (1.1 in) | Kamakura period, first half of 13th century | 80.4 cm (31.7 in) | Agency for Cultural Affairs, Tokyo |

| Tachi[69][70] | Norikuni (則国) | Norikuni (則国) | Curvature 2.1 cm (0.83 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century | 74.7 cm (29.4 in) | Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto |

Rai school

The Rai school, active from the mid-Kamakura period through the Nanboku-chō period, succeeded the Awataguchi school as the foremost school in Yamashiro Province.[62] It was founded in the 13th century either by Kuniyuki or his father Kuniyoshi from the Awataguchi school.[52][71] The name, "Rai" refers to the fact that smiths of this school preceded their signatures with the character "来" ("rai").[62] Rai school works show some characteristics of the later Sōshū tradition, especially in the work of Kunitsugu.[71]

Rai school sugata resembles that of the late Heian/early Kamakura period being both gentle and graceful, but grander and with a more vigorous workmanship. Starting with Kunimitsu, the kissaki becomes larger. The jihada is small-grain mokume-hada, dense with ji-nie, yubashiri and chikei. The quality of the jigane is slightly inferior to that of the Awataguchi school. The hamon shows medium suguha with chōji midare.[71]

| Tachi[49] | Kuniyuki (国行) | Rai Kuniyuki (来国行) | Blade by the founder of the Rai school; handed down in the Matsudaira clan lords over the Akashi Domain in Harima Province; curvature 3.0 cm (1.2 in) | mid-Kamakura period | 76.5 cm (30.1 in) | The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords (日本美術刀剣保存協会 Zaidanhōjin Nippon Bijutsu Tōkenhozonkyōkai), Tokyo |

| Tachi | Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) | Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) | — |

Kamakura period | — |

Private, Tokyo |

| Tantō[72] | Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) | Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) | Uchi-zori | Kamakura period, 1316 | 25.1 cm (9.9 in) | Atsuta Shrine, Nagoya, Aichi |

| Tantō | Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) | Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) | — |

Kamakura period | — |

Kurokawa Institute of Ancient Cultures (黒川古文化研究所 Kurokawa Kobunka Kenkyūjo), Nishinomiya, Hyōgo |

| Kodachi[73] | Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) | Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) | Curvature: 1.67 cm (0.66 in) | Kamakura period | 54.4 cm (21.4 in) | Futarasan Shrine, Nikkō, Tochigi |

| Tachi[74][75] | Rai Kunimitsu (来国光) | Rai Kunimitsu (来国光) | Handed down in the Matsudaira clan, used by Matsudaira Tadaaki in the Siege of Osaka; later owned by the Iwasaki family, founders of Mitsubishi, then by Yamagata Aritomo and by Emperor Meiji | Kamakura period, 14th century | 80.7 cm (31.8 in) | Kyushu National Museum, Dazaifu, Fukuoka |

| Tachi[76][77] | Rai Kunimitsu (来国光) | Rai Kunimitsu (来国光) | Presented to the crown prince, the later Emperor Taishō, by Tokugawa Iesato; particularly strong curvature 3.5 cm (1.4 in) | Kamakura period, 1327 | 79.1 cm (31.1 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[78] | Work of Rai Magotarō (来孫太郎作 Rai Magotarōsaku) | Rai Magotarō (来孫太郎) | — |

Kamakura period, 1292 | 77.3 cm (30.4 in) | Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya, Aichi |

| Tantō or Yūraku Rai Kunimitsu (有楽来国光)# | Rai Kunimitsu (来国光) | Rai Kunimitsu (来国光) | Oda Nagamasu, also known as Urakusai (有楽斎) received this sword from Toyotomi Hideyori; later handed down in the Maeda clan | Kamakura period | 27.6 cm (10.9 in) | Private, Shizuoka |

| Tantō | Rai Kunitsugu (来国次) | Rai Kunitsugu (来国次)* | — |

Kamakura period, 14th century | 32.7 cm (12.9 in) | Private, Tokyo |

Sōshū or Sagami Province

The Sōshū (or Sagami) tradition owes its origin to the patronage of the Kamakura shogunate set up by Minamoto no Yoritomo in 1185 in Kamakura, Sagami Province.[45][52] Though the conditions for swordsmithing were not favourable, the intense military atmosphere and high demand for swords helped to establish the school.[45] The tradition is believed to have originated in 1249, when Awataguchi Kunitsuna from the Yamashiro tradition forged a tachi for Hōjō Tokiyori.[52] Other recognized founders were Ichimonji Sukezane and Saburo Kunimune, both from the Bizen tradition.[nb 13][79][45] The Sōshū tradition's popularity increased after the Mongol invasions (1274, 1281).[27] It is characterized by tantō daggers that were produced in large quantities; but also tachi and katana were forged.[52] With the exception of wider and shorter so called "kitchen knives" (hōchō tantō), daggers were 24–28 cm (9.4–11.0 in) long, uncurved or with a slight curve toward the cutting edge (uchi-zori).[42]

During the early Sōshū tradition, from the late Kamakura period to the beginning of the Nanboku-chō period, the smiths' goal was to produce swords that exhibited splendor and toughness, incorporating some of the best features of the Bizen and Yamashiro traditions.[79] The Midare Shintōgo by Awataguchi Kunitsuna's son, Shintōgo Kunimitsu, is considered to be the first true Sōshū tradition blade.[79] Shintōgo Kunimitsu was the teacher of Yukimitsu and of Masamune who is widely recognized as Japan's greatest swordsmith.[52] Together with Sadamune, whose work looks modest compared to Masamune's, these are the most representative smiths of the early Sōshū tradition.[79] Sōshū tradition sugata is characterized by a shallow torii-zori, bigger mihaba, smaller kasane, medium or large kissaki. The jihada is mostly itame-hada with ji-nie and chikei and the hamon is gunome,[j 33] midareba[j 34] and hitatsura. Nie, sunagashi[j 35] and kinsuji[j 36] are often visible in the hamon.[23]

| Tantō[80][81] | Yukimitsu (行光) | Yukimitsu (行光) | Formerly owned by the Maeda clan; blade exhibits intermediary style between straight tempering pattern used by Yukimitsu's teacher, Gokunimitsu, and curved-wave tempering pattern of his student, Masamune | Kamakura period, 14th century | 26.2 cm (10.3 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tantō | Kunimitsu (国光) | Shintōgo Kunimitsu | — |

Kamakura period, around Einin to Shōwa eras (1293–1317) | 25.5 cm (10.0 in) | Private, Tokyo |

| Tantō | Kunimitsu (国光) | Shintōgo Kunimitsu | — |

Kamakura period, around Einin to Shōwa eras (1293–1317) | — |

Private, Osaka |

| Tantō or Aizu Shintōgo (会津新藤五)#[82][83] | Kunimitsu (国光) | Shintōgo Kunimitsu | Formerly owned by Gamō Ujisato. The name, "Aizu", refers to the Aizu area which he controlled. | Kamakura period, late 13th century | 25.5 cm (10.0 in) | Private, Hiroshima |

| Katana[84] | Unsigned | Masamune | With an inscription in gold inlay from 1609: Owned by Shiro Lord of Izumi (城和泉守所持 Shiro Izumi no Kami shoji) and Masamune Suriage Honami (正宗磨上本阿) (authenticated by Honami Kōtoku as Masamune sword); formerly in possession of the Tsugaru clan; curvature 2.1 cm (0.83 in) | Kamakura period, 14th century, before Gentoku era (1329) | 70.8 cm (27.9 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Katana or Kanze Masamune (観世正宗)# | Unsigned | Masamune | Formerly in the possession of the Kanze school, a Noh school | Kamakura period, around Shōō to Karyaku eras (1288–1328) | 64.4 cm (25.4 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Katana or Tarō-saku Masamune (太郎作正宗)# | Unsigned | Masamune | — |

Kamakura period, around Shōō to Karyaku eras (1288–1328) | 64.3 cm (25.3 in) | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |

| Katana or Nakatsukasa Masamune (中務正宗)#[85] | Unsigned | Masamune | With a gold inlay inscription: Masamune Honami Kaō (正宗本阿花押); formerly held by Honda Tadakatsu whose official rank was Nakatsukasa Daisuke; later handed down in the Tokugawa clan; curvature: 1.7 cm (0.67 in) | Kamakura period, 14th century, before Gentoku era (1329) | 67.0 cm (26.4 in) | Agency for Cultural Affairs, Tokyo |

| Tantō or Hyūga Masamune (日向正宗)#[86] | Unsigned | Masamune | Formerly in the possession of Ishida Mitsunari who gave this sword to the husband of his younger sister; the sword was stolen during the Battle of Sekigahara by Mizuno Katsushige, governor of Hyūga Province | Kamakura period, around Shōō to Karayku eras (1288–1328) | 24.8 cm (9.8 in) | Mitsui Memorial Museum, Tokyo |

| Tantō or Kuki Masamune (九鬼正宗)#[87] | Unsigned | Masamune | — |

Kamakura period, 14th century, before Gentoku era (1329) | 24.8 cm (9.8 in) | Hayashibara Museum of Art, Okayama, Okayama |

| Tantō or "Kitchen knife" Masamune (庖丁正宗 Hōchō Masamune)#[76][87] | Unsigned | Masamune | The name "Kitchen knife" refers to the unusually short and wide shape of the knife. In addition to this item, there are two other national treasure "kitchen knives" by Masamune. | Kamakura period, 14th century, before Gentoku era (1329) | 24.1 cm (9.5 in) | Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya, Aichi |

| Tantō or Terasawa Sadamune (寺沢貞宗)#[76][88] | Unsigned | Sadamune | Name derives from the fact that this sword was a favorite of Terasawa Shima no Kami Hirotaka who passed it on to Tokugawa Hidetada and further to Tokugawa Yorinori, lord of the Kishu fief | Kamakura period, mid 14th century, around Gentoku to Kemmu eras (1329–1338) | 29.4 cm (11.6 in) | Agency for Cultural Affairs, Tokyo |

| Tantō or "Kitchen knife" Masamune (庖丁正宗 Hōchō Masamune)#[87] | Unsigned | Masamune | The name "Kitchen knife" refers to the unusually short and wide shape of the knife. In addition to this item, there are two other national treasure "kitchen knives" by Masamune. | Kamakura period, 14th century, before Gentoku era (1329) | 21.8 cm (8.6 in) | Eisei Bunko Museum, Tokyo |

| Tantō or "Kitchen knife" Masamune (庖丁正宗 Hōchō Masamune)# | Unsigned | Masamune | The name "Kitchen knife" refers to the unusually short and wide shape of the knife. In addition to this item, there are two other national treasure "kitchen knives" by Masamune. | Kamakura period, around Shōō to Karayku eras (1288–1328) | 21.7 cm (8.5 in) | Kinshūkai (錦秀会), Osaka |

| Tantō or Tokuzen-in Sadamune (徳善院貞宗)#[86][87] | Unsigned | Sadamune | Maeda Gen'i, also known as Abbot Tokuzen-in (a temple name) received this dagger from Toyotomi Hideyoshi; later it was handed down in the Tokugawa clan and the Saijō branch of the Matsudaira clan | Kamakura period, 14th century, around Gentoku to Kemmu eras (1329–1338) | 35.5 cm (14.0 in) | Mitsui Memorial Museum, Tokyo |

| Tantō or Fushimi Sadamune (伏見貞宗)#[89] | Unsigned | Sadamune | With a red lacquer stamp by a Honami sword appraiser | Kamakura period, 14th century, around Gentoku to Kemmu eras (1329–1338) | — |

Kurokawa Institute of Ancient Cultures (黒川古文化研究所 Kurokawa Kobunka Kenkyūjo), Nishinomiya, Hyōgo |

| Katana or Tortoise shell Sadamune (亀甲貞宗 Kikkō Sadamune)#[87][90] | Unsigned | Sadamune | Name ("tortoise shell") refers to an engraving on the tang: a chrysanthemum within a hexagon, resembling a tortoise shell; curvature: 2.4 cm (0.94 in) | Kamakura period, 14th century, around Gentoku to Kemmu eras (1329–1338) | 70.9 cm (27.9 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[91] | Sukezane (助真) | Kamakura Ichimonji Sukezane (鎌倉一文字助真) | Sword by the founder of the Kamakura Ichimonji school; curvature 1.8 cm (0.71 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century, around Bun'ei era (1264–1275) | 67.0 cm (26.4 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[76] | Sukezane (助真) | Kamakura Ichimonji Sukezane (鎌倉一文字助真) | Sword by the founder of the Kamakura Ichimonji school; formerly held by Tokugawa Ieyasu | Kamakura period, 13th century, around Bun'ei era (1264–1275) | 71.2 cm (28.0 in) | Nikkō Tōshō-gū, Nikkō, Tochigi |

Bizen Province

Bizen Province became an early center of iron production and swordmaking because of the proximity to the continent.[17][43] Conditions for sword production were ideal: good iron sand; charcoal and water were readily available; and the San'yōdō road ran right through the province.[92] Bizen has been the only province to produce swords continuously from the Heian to the Edo period.[92] In kotō times, a large number of skilled swordsmiths lived along the lower reaches of the Yoshii river around Osafune making it the largest center of sword production in Japan.[17][93][94] Bizen province not only dominated in the numbers of blades produced but also in quality; and Bizen swords have long been celebrated for excellent swordsmanship.[44][94] The peak of the Bizen tradition, marked by a gorgeous and luxurious style, was reached in the mid-Kamakura period.[94] Later, in the 13th century, the Ichimonji and Osafune schools, the mainstream schools of Bizen Province, maintained the Heian style of the Ko-Bizen, the oldest school in Bizen province.[43][95] After the 13th century, swords became wider and the point (kissaki) longer, most likely as a response to the thick armour of the invading Mongols.[43] Mass production due to heavy demand for swords from the early 15th to the 16th century led to a lower quality of blades.[43] The Bizen tradition is associated with a deep koshi-zori, a standard mihaba, bigger kasane with medium kissaki. The jihada is itame-hada often accompanied by utsuri.[j 37] The hamon is chōji midare in nioi deki.[23]

Ko-Bizen

The oldest branch of swordmaking in Bizen Province is the Ko-Bizen (old Bizen) school.[96] It was founded by Tomonari[nb 14] who lived around the early 12th century.[17][96] The school flourished in the late Heian period (10th–12th century) and continued into the Kamakura period.[43][94] Three great swordsmiths—Kanehira, Masatsune and Tomonari—are associated with the school.[43] Ko-Bizen tachi are generally thin,[nb 15] have a strong koshi-zori and small kissaki. The grain is itame-hada or small itame-hada and the hamon is small midare[j 34] made of nie in combination with chōji and gunome.

| Tachi | Made by Tomonari from Bizen Province (備前国友成造 Bizen no kuni Tomonari tsukuru) | Tomonari (友成)[nb 16] | Curvature: 2.4 cm (0.94 in) | Heian period, 11th century | 80.3 cm (31.6 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[97] | Work of Tomonari (友成作 Tomonari saku) | Tomonari (友成)[nb 16] | Handed down through Taira no Munemori; curvature: 3.0 cm (1.2 in) | Heian period, 12th century | 79.3 cm (31.2 in) | Itsukushima Shrine, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima |

| Tachi or "Great Kanehira" (大包平 Ōkanehira)#[76][98] | Work of Kanehira from Bizen Province" (備前国包平作 Bizen no kuni Kanehira tsuku) | Kanehira (包平) | Name ("Ōkanehira") refers to the extraordinary size of the blade; unusual signature for Kanehira who usually used a two character signature; owned by Ikeda Terumasa and passed down in the Ikeda clan; curvature 3.5 cm (1.4 in) | Heian period, 12th century | 89.2 cm (35.1 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[99] | Masatsune (正恒) | Masatsune (正恒) | Tokugawa Munechika received the sword in 1745 from Tokugawa Yoshimune | Heian period, mid-12th century, around Hōgen era (1156–1159) | 72.0 cm (28.3 in) | Agency for Cultural Affairs, Tokyo |

| Tachi[76] | Masatsune (正恒) | Masatsune (正恒) | — |

Heian period, mid-12th century, around Hōgen era (1156–1159) | 74.2 cm (29.2 in) | Agency for Cultural Affairs, Tokyo |

| Tachi[100][101] | Masatsune (正恒) | Masatsune (正恒) | The sword passed from Tokugawa Yoshimune on his retirement in 1745 to Tokugawa Munekatsu and later on to Tokugawa Munechika; curvature: 2.8 cm (1.1 in), breadth at butt: 2.9 cm (1.1 in) | Heian period, mid-12th century, around Hōgen era (1156–1159) | 71.8 cm (28.3 in) | Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya, Aichi |

| Tachi[59][83] | Masatsune (正恒) | Masatsune (正恒) | — |

Heian period, mid-12th century, around Hōgen era (1156–1159) | 77.6 cm (30.6 in) | Private (Aoyama Kikuchi), Tokyo |

| Tachi | Masatsune (正恒) | Masatsune (正恒) | — |

Heian period, mid-12th century, around Hōgen era (1156–1159) | — |

Private, Osaka |

| Tachi | Sanetsune (真恒) | Sanetsune (真恒) | Curvature: 3.9 cm (1.5 in) | Heian period, late 11th century, around Jōryaku are (1077–1081) | 89.4 cm (35.2 in) | Kunōzan Tōshō-gū, Shizuoka, Shizuoka |

| Tachi[nb 17][76][102] | Work of Nobufusa (信房作 Nobufusa-saku) | Nobufusa (信房) | Curvature: 2.3 cm (0.91 in) | Heian period, 12th century | 76.1 cm (30.0 in) | Chidō Museum, Tsuruoka, Yamagata |

Ichimonji school

The Ichimonji school was founded by Norimune in the late Heian period.[43] Together with the Osafune it was one of the main branches of the Bizen tradition and continued through the Kamakura period with a peak of prosperity before the mid-Kamakura period.[94][95] The name Ichimonji (一文字, lit. character "one") refers to the signature (mei) on swords of this school. Many smiths signed blades with only a horizontal line (read as "ichi", translated as "one"); however signatures exist that contain only the smith's name, or "ichi" plus the smith's name, and unsigned blades exist as well.[95] From the early Ichimonji school (Ko-Ichimonji), the "ichi" signature looks like a diagonal line and might have been a mark instead of a character. From the mid-Kamakura period however, "ichi" is definitely the character and not a mark.[95] Some Ichimonji smiths lived in Fukuoka village, Osafune and others in Yoshioka village. They are known as Fukuoka-Ichimonji and Yoshioka-Ichimonji respectively, and were typically active in the early to mid-Kamakura period (Fukuoka-Ichimonji) and the late-Kamakura period (Yoshioka-Ichimonji) respectively.[95]

The workmanship of early Ichimonji smiths such as Norimune resembles that of the Ko-Bizen school: tachi have a narrow mihaba, deep koshi-zori, funbari and an elegant sugata with small kissaki. The hamon is small midare or small midare with small chōji midare in small nie.[95]

Around the middle Kamakura period tachi have a wide mihaba and grand sugata with medium kissaki such as ikubi kissaki. The hamon is large chōji midare or juka chōji[j 38] in nioi deki and irregular width. Particularly the hamon of tachi with just the "ichi" signature is wide chōji. The hamon of this period's Ichimonji school is one of the most gorgeous amongst kotō smiths and comparable to Masamune and his students' works.[95] The most characteristic works for mid-Kamakura period Ichimonji school were produced by Yoshifusa, Sukezane and Norifusa.[95] Yoshifusa, who left the largest number of blades, and Norifusa might each in fact have been several smiths using the same name.[95]

| Tachi | ichi (一) | Tomonari (友成) | — |

Kamakura period | — |

Makiri Corporation (株式会社マキリ Kabushikigaisha Makiri), Numazu, Shizuoka |

| Tachi or Nikkō Ichimonji (日光一文字)#[103] | Unsigned | Fukuoka Ichimonji (福岡一文字) | Part of the Kuroda family collection, handed down in the Hōjō clan; curvature: 2.4 cm (0.94 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century | 67.8 cm (26.7 in) | Fukuoka City Museum, Fukuoka, Fukuoka |

| Tachi[59] | Unsigned | Fukuoka Ichimonji (福岡一文字) | Temper pattern resembles the feather of a pheasant: Yamatorige (山鳥毛) | Kamakura period | 79.0 cm (31.1 in) | Private, Okayama |

| Tachi[104] | Norimune (則宗) | Norimune (則宗)^ | Curvature: 2.8 cm (1.1 in) | early Kamakura period, around Genryaku to Jōgen eras (1184–1211) | 78.4 cm (30.9 in) | Hie Shrine, Tokyo |

| Tachi[105] | Yoshifusa (吉房) | Yoshifusa (吉房) | Sword of Oda Nobunaga whose son, Oda Nobukatsu, used it to slay Okada Sukesaburō in the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute

Also known as Okada slayer (岡田切 Okada-giri), curvature: 2.1 cm (0.83 in) |

Kamakura period, 13th century | 69.1 cm (27.2 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[106] | Yoshifusa (吉房) | Yoshifusa (吉房) | Formerly in the possession of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, later bestowed on Takekoshi Masanobu, a retainer of Tokugawa Ieyasu; subsequently owned by Takekoshi's descendants | Kamakura period, 13th century | 70.6 cm (27.8 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi | Yoshifusa (吉房) | Yoshifusa (吉房) | — |

Kamakura period, 13th century | — |

Private, Tokyo |

| Tachi [76][107] | Yoshifusa (吉房) | Fukuoka Yoshifusa (福岡吉房) | In the possession of many people such as the Kishū-Tokugawa family; handed down in the Taira clan; curvature: 2.65 cm (1.04 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century | 71.2 cm (28.0 in) | Hayashibara Museum of Art, Okayama, Okayama |

| Tachi[83] | Yoshifusa (吉房) | Fukuoka Yoshifusa (福岡吉房) | Handed down in the Tokugawa clan | Kamakura period, 13th century | 73.9 cm (29.1 in) | Private, Hiroshima |

| Tachi | Yoshihira (吉平) | Fukuoka Yoshihira (福岡吉平) | — |

Kamakura period, around Ninji to Kenchō eras (1240–1256) | — |

Private, Tokyo |

| Tachi[108] | Sukekane (助包) | Fukuoka Sukekane (福岡助包) | Handed down in the Tottori branch of the Ikeda clan | Kamakura period | 77.7 cm (30.6 in) | Private, Osaka |

| Tachi[59][83] | Norifusa (則房) | Fukuoka Norifusa (福岡則房) | Handed down in the Tokugawa clan; curvature: 3.2 cm (1.3 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century | 77.3 cm (30.4 in) | Private, Hiroshima |

| Katana | Unsigned | Fukuoka Norifusa (福岡則房) | — |

Kamakura period | — |

Private, Tokyo |

| Tachi | Sakon Shōgen Sukemitsu living in Yoshioka in Bizen Province (備前国吉岡住左近将監紀助光 Bizen no kuni Yoshioka jū Sakon Shōgen ki Sukemitsu), O Great God of Arms, I beseech your aid against my enemy! (南无 八幡大菩薩 Namu Hachiman Daibosatsu) | Yoshioka Sukemitsu (吉岡助光) | Curvature: 3.9 cm (1.5 in) | Kamakura period, March 1322 | 82.4 cm (32.4 in) | Private, Osaka |

| Naginata[109] | Ichi Sakon Shōgen Sukemitsu living in Yoshioka in Bizen Province (一備州吉岡住左近将監紀助光 ichi Bishū Yoshioka-jū Sakon Shōgen ki no Sukemitsu) | Yoshioka Sukemitsu (吉岡助光) | Handed down in the Kaga branch of the Maeda clan | Kamakura period, 1320 | 56.7 cm (22.3 in) | Private, Osaka |

Osafune school

Founded by Mitsutada in the mid-Kamakura period in Osafune, the Osafune school continued through to the end of the Muromachi period.[93][94] It was for a long time the most prosperous of the Bizen schools and a great number of master swordsmiths belonged to it.[93] Nagamitsu (also called Junkei Nagamitsu), the son of Mitsutada, was the second generation, and Kagemitsu the third generation.[93]

Osafune sugata is characteristic for the period and similar to that of the Ichimonji school: a wide mihaba and ikubi kissaki. After the 13th century the curve moved from koshi-zori to torii-zori.[43] Other stylistic features depend on the swordsmith. In the hamon, Mitsutada adopted the Ichimonji style of large chōji midare mixed with juka chōji and a unique kawazuko chōji;[j 39] Nagamitsu produced also chōji midare hower with a different pattern and mixed with considerable gunome midare. Starting with Kagemitsu the hamon became suguha and gunome midare. Kagemitsu is also credited with the invention of kataochi gunome.[j 40] Mitsutada's bōshi is midare komi[j 41] with short kaeri[j 42] or yakitsume.[j 43] Nagamitsu and Kagemitsu use a sansaku bōshi.[j 44] Kagemitsu is also known as one of the finest engravers particularly through his masterpiece Koryū Kagemitsu.[93]

| Tachi[110][111] | Kagemitsu living in Osafune in Bizen Province (備前国長船住景光 Bizen no kuni Osafune-jū Kagemitsu) | Kagemitsu (景光) | Sword of Kusunoki Masashige, also called Little Dragon Kagemitsu (小龍景光 Koryū Kagemitsu) after a relief on the face of the blade, curvature: 2.7 cm (1.1 in) | Kamakura period, May 1322 | 80.6 cm (31.7 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Katana | Unsigned | Mitsutada (光忠) | Also called Ikoma Mitsutada (生駒光忠) after the former owner, Ikoma Chikamasa; with a kaō and a gold inlay inscription: Mitsutada (光忠), made by the connoisseur Honami Kōtoku (本阿弥光徳) | Kamakura period, around Ryakunin to Kangen era (1238–1247) | — |

Eisei Bunko Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[76][112] | Mitsutada (光忠) | Mitsutada (光忠) | Tokugawa Tsunanari received this sword from Tokugawa Tsunayoshi in 1698; curvature: 2.3 cm (0.91 in) | Kamakura period, around Ryakunin to Kangen era (1238–1247) | 72.4 cm (28.5 in) | Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya, Aichi |

| Katana | Mitsutada (光忠) | Mitsutada (光忠) | Inscription in gold inlay | Kamakura period, around Ryakunin to Kangen era (1238–1247) | — |

Private, Osaka |

| Tachi or Daihannya Nagamitsu (大般若長光)#[113] | Nagamitsu (長光) | Junkei Nagamitsu (長光) | The name ("Daihannya") refers to the Daihannya sutra. The value of the sword during the Muromachi period, 600 kan, was associated with the sutra's 600 volumes; said to have belonged to the Ashikaga clan, later in the possession of Oda Nobunaga who gave it to Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Battle of Anegawa, who then gave it to Okudaira Nobumasa at the Battle of Nagashino; curvature: 2.9 cm (1.1 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century, around Kenchō to Shōō eras (1249–1293) | 73.6 cm (29.0 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi or Tōtōmi Nagamitsu (遠江長光)#[114] | Nagamitsu (長光) | Junkei Nagamitsu (長光) | Stolen by Akechi Mitsuhide from Azuchi Castle; later in the possession of Maeda Toshinaga, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi and in 1709 it passed from Tokugawa Ienobu to Tokugawa Yoshimichi | Kamakura period, 13th century, around Kenchō to Shōō eras (1249–1293) | 72.4 cm (28.5 in) | Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya, Aichi |

| Tachi | Nagamitsu (長光) | Junkei Nagamitsu (長光) | — |

Kamakura period, 13th century, around Kenchō to Shōō eras (1249–1293) | — |

Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[115] | Made by Sakon Shōgen Nagamitsu living in Osafune in Bizen province (備前国長船住左近将監長光造 Bizen no kuni Osafune no jū Sakon Shōgen Nagamitsu-zō) | Junkei Nagamitsu (長光) | Curvature: 2.7 cm (1.1 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century, around Kenchō to Shōō eras (1249–1293) | 78.7 cm (31.0 in) | Hayashibara Museum of Art, Okayama, Okayama |

| Tachi | Three Avatars of Kumano (熊野三所権現長光 Kumano Sansho Gongen Nagamitsu) | Junkei Nagamitsu (長光) | Curvature: 2.9 cm (1.1 in), also called: "Sword of the three temples" | Kamakura period, 13th century, around Kenchō to Shōō eras (1249–1293) | 78.0 cm (30.7 in) | Private, Shizuoka |

| Tachi[116] | Sahyōe-no-jō (lit. left palace guard) Kagemitsu living in Osafune in Bizen Province (備前国長船住左兵衛尉景光 Bizen no kuni Osafune no jū Sahyōe no jō Kagemitsu) | Kagemitsu (景光) | — |

Kamakura period, July, 1329 | 82.4 cm (32.4 in) | Saitama Prefectural Museum of History and Folklore, Saitama, Saitama |

| Naginata[76][117] | Made by Nagamitsu living in Osafune in Bizen Province (備前国長船住人長光造 Bizen no kuni Osafune-jū Nagamitsu tsukuru) | Nagamitsu (長光) | Length of tang: 63.5 cm (25.0 in) | Kamakura period, 14th century | 44.2 cm (17.4 in) | Sano Art Museum (佐野美術館 Sano Bijutsukan), Mishima, Shizuoka |

| Tantō[nb 18][76][118] | Kagemitsu living in Osafune in Kibi Province (備州長船住景光 Bishū Osafune-jū Kagemitsu) | Kagemitsu (景光) | Formerly in the possession of Uesugi Kenshin; with an engraving: Chichibu Daibosatsu (秩父大菩薩) on the blade; slight curvature | Kamakura period, 1323 | 28.3 cm (11.1 in) | Saitama Prefectural Museum of History and Folklore, Saitama, Saitama |

| Tachi[nb 19][76][119] | Kagemitsu (景光) | Kagemitsu (景光) | Presented to Tadatsugu (忠次) by Oda Nobunaga for good service in the Battle of Nagashino; curvature: 2.9 cm (1.1 in) | Kamakura period, 14th century towards 1333 | 77.3 cm (30.4 in) | Chidō Museum, Tsuruoka, Yamagata |

| Tachi | Chikakage living in Osafune in Bizen Province (備前国長船住近景 Bizen no kuni Osafune-jū Chikakage) | Chikakage (近景) | Curvature: 2.8 cm (1.1 in) | Kamakura period, 1329 | 80.5 cm (31.7 in) | Private, Osaka |

| Tantō | Nagashige living in Osafune in Kibi Province (備州長船住長重 Bishū Osafune-jū Nagashiga) | Nagashige (長重) | Slight curvature towards the cutting edge (uchi-zori) | Nanboku-chō period, 1334 | 26.06 cm (10.26 in) | Private, Tokyo |

| Ōdachi[76][120] | Tomomitsu living in Osafune in Kibi Province (備州長船倫光 Bishū Osafune Tomomitsu) | Tomomitsu (倫光) | Handed down in the Bizen Osafune Kanemitsu branch; curvature: 5.8 cm (2.3 in) | Nanboku-chō period, February, 1366 | 126 cm (50 in) | Futarasan Shrine, Nikkō, Tochigi |

Saburo Kunimune school

Like the Osafune school, the Saburo Kunimune school was located in Osafune, however the swordsmiths are from a different lineage than those of Mitsutada and his school.[121][122] The name, "saburo", refers to the fact that Kunimune, the founder of the school, was the third son of Kunizane.[122] Kunimune later moved to Sagami Province to found the Sōshū tradition together with Ichimonji Sukezane.[121] There were two generations of Kunimune, and their work is very difficult to distinguish.[121][122] This school's workmanship is similar to that of other smiths of the time but with a slightly coarse jihada and with hajimi.[j 45][121]

| Tachi[123] | Kunimune (国宗) | Kunimune (国宗)^ | Curvature: 3.3 cm (1.3 in), breadth at butt: 3.3 cm (1.3 in), breadth near kissaki: 2.15 cm (0.85 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century | 81.7 cm (32.2 in) | Nikkō Tōshō-gū, Nikkō, Tochigi |

| Tachi[123] | Kunimune (国宗) | Kunimune (国宗)^ | Confiscated by the GHQ in the aftermath of World War II and subsequently lost, but re-discovered by chance in 1963 and returned to Terukuni shrine a year later by an American Dr. Walter Compton (owner of one of the greatest Japanese sword collection outside Japan, he returned Kunimune by himself and without seeking any compensation) ; curvature: 2.7 cm (1.1 in), breadth at butt: 3.3 cm (1.3 in), breadth near kissaki: 2.1 cm (0.83 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century | 81.3 cm (32.0 in) | Terukuni Shrine, Kagoshima, Kagoshima |

| Tachi[83] | Kunimune (国宗) | Kunimune (国宗)^ | — |

Kamakura period, 13th century | 72.6 cm (28.6 in) | Private,Komatsu Yasuhiro Industries (小松安弘興産 Komatsu Yasuhiro Kōsan), Tokyo |

| Tachi[87][123][124] | Kunimune (国宗) | Kunimune (国宗)^ | Since 1739 handed down in the Owari branch; curvature: 2.7 cm (1.1 in), breadth at butt: 3.2 cm (1.3 in), breadth near kissaki: 2.1 cm (0.83 in) | Kamakura period, 13th century | 80.1 cm (31.5 in) | Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya, Aichi |

Other countries

Etchū Province

Two of Masamune's ten excellent students (juttetsu), Norishige and Gō Yoshihiro, lived in Etchū Province at the end of the Kamakura period.[125] While none of Gō Yoshihiro's works is signed, there are extant signed tantō and tachi by Norishigi.[56] One tantō by Norishige and two katana by Gō Yoshihiro have been designated as national treasures. Generally Norishige's sugata is characteristic of the time: tantō are with not-rounded fukura[j 46] and uchi-zori, thick kasane and steep slopes of iori-mune.[j 47] The jihada is matsukawa-hada[j 48] with thick ji-nie, lots of chikei along the o-hada.[j 49] The jigane is not equal to that of Masamune or Gō Yoshihiro. Norishige hamon is relatively wide and made up of bright and larger nie based in notare[j 50] mixed with suguha chōji midare or with gunome midare. Gō Yoshihiro produced various sugata with either small kissaki and narrow mihaba or with wider mihaba and larger kissaki. His jihada is identical to that of the Awataguchi school in Yamashiro Province: soft jigane, small mokume-hada mixed with wavy ō-hada. Thick ji-nie becomes yubashiri with chikei. The hamon has an ichimai[j 51] or ichimonji bōshi[j 52] with ashi[j 53] and abundant nie. The kaeri is short or yakitsume.[56]

| Tantō[87] | Norishige (則重) | Norishige (則重)* | Also called Japan's best Norishige (日本一則重 Nihonichi Norishige) | late Kamakura period, around Enkyō to Karyaku era (1308–1329) | 24.6 cm (9.7 in) | Eisei Bunko Museum, Tokyo |

| Katana or Tomita Gō (富田江)# | Unsigned | Gō Yoshihiro (郷義弘, 江義弘)* | Handed down in the Toda clan (富田氏 Toda-shi) | early Nanboku-chō period, 14th century | — |

Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |

| Katana or Inaba Gō (稲葉江)# | Unsigned | Gō Yoshihiro (郷義弘, 江義弘)* | With an inscription in gold inlay by Honami Kotoku (本阿光徳): December 1585 Honami Kotoku (天正十三 十二月 日 江 本阿弥磨上之(花押) 所持 稲葉勘右衛門尉 tenshō jūsan jūnigatsu-hi Gō-Honami majō-kore shoji Inaba kaneumon no jō); handed down in the Inaba clan; curvature: 2 cm (0.79 in) | early Nanboku-chō period, 14th century | 70.8 cm (27.9 in) | Private, Tokyo |

Bitchū Province

The mainstream school of Bitchū Province was the Aoe school named after a place presently located in Kurashiki.[126] It appeared at the end of the Heian period and thrived in the ensuing Kamakura period.[127] The quality of Aoe swords was swiftly recognized, as 3 of the 12 smiths at Emperor Go-Toba's court were of this school.[126] Five tachi blades of the early aoe school (ko-aoe, before the Ryakunin era, 1238/39) have been designated national treasures.[126] The ko-aoe school consists of two families employing a similar style of swordsmanship that did not deviate with time.[126] The first family was represented by the founder Yasutsugu[nb 20] and, among others, Sadatsugu, Tametsugu, Yasutsugu (the one in this list) and Moritoshi.[126] The second family, named "Senoo", was founded by Noritake who was followed by Masatsune, and others.[126] Ko-Aoe produced slender tachi with small kissaki and deep koshi-zori. A distinctive feature of this school is the jihada which is chirimen-hada[j 54] and sumigane[j 55] (dark and plain steel). The hamon is midare based on suguha with ashi and yō.[j 56] The boshi is midare komi or suguha with a short kaeri, yakitsume.[128]

| Tachi[68] | Sadatsugu (貞次) | Sadatsugu (貞次)^ | Curvature: 2.4 cm (0.94 in), breadth at butt: 2.9 cm (1.1 in) | Kamakura period, first half of 13th century | 77.1 cm (30.4 in) | Private, Tokyo |

| Tachi | Moritoshi (守利) | Moritoshi (守利) | — |

Kamakura period, around Gennin era | — |

Private, Osaka |

| Tachi[68][129] | Masatsune (正 恒) | Masatsune (正恒) | Presented to the shrine Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū by Tokugawa Yoshimune in 1736; curvature: 3 cm (1.2 in), breadth at butt: 3 cm (1.2 in) | Kamakura period, first half of 13th century | 78.2 cm (30.8 in) | Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū, Kamakura, Kanagawa |

| Tachi[68] | Tametsugu (為次) | Tametsugu (為次) | Also called Kitsunegasaki (狐ヶ崎) after a place in present Shimizu-ku, Shizuoka; curvature 3.4 cm (1.3 in), breadth at butt: 3.2 cm (1.3 in) | Kamakura period, first half of 13th century | 78.8 cm (31.0 in) | Kitsukawahōkōkai (吉川報效会), Iwakuni, Yamaguchi |

| Tachi[68][130] | Yasutsugu (康次) | Yasutsugu (康次) | Presented to Shimazu Yoshihisa by Ashikaga Yoshiaki; curvature 3.5 cm (1.4 in), breadth at butt 3.6 cm (1.4 in) | Kamakura period, first half of 13th century | 85.2 cm (33.5 in) | Sukyo Mahikari, Takayama, Gifu |

Hōki Province

The work of Yasutsuna who lived in Hōki Province predates that of the Ko-Bizen school. Though old sources date his activity to the early 9th century, he was most likely a contemporary of Sanjō Munechika. The first forging of the first curved Japanese swords has been attributed to these two smiths.[131] Yasutsuna founded the school with the same name. Two tachi of the Yasutsuna school have been designated as national treasures: one, the Dōjigiri Yasutsuna by Yasutsuna has been named the "most celebrated of all Japanese swords"; the other is by his student Yasuie.[132] The Dōjigiri has torii-zori, distinct funbari, small kissaki; its jihada is mokume-hada with abundant ji-nie. The hamon is small midare consisting of thick nioi and abundant small nie. There are many vivid ashi visible. Yō and kinsuji appear inside the hamon.[131][133] The work of other school members including Yasuie's is characterized by coarse mokume-hada, black jigane, ji-nie and chikei. The hamon is small midare consisting of nie with kinsuji and sunagashi.[131]

| Tachi[134] | Yasuie (安家) | Yasuie (安家) | With a black-tinged finish and distinctive speckled pattern, typical for swords from Hōki Province, passed down in the Kuroda family, only work definitely by Yasuie; curvature 3.2 cm (1.3 in) | Heian period, 12th century, around Heiji era (1159–1160) | 77.3 cm (30.4 in) | Kyoto National Museum, Kyoto |

| Tachi or Monster Cutter (童子切安綱 Dōjigiri Yasutsuna)#[28][132][135][136] | Yasutsuna (安綱) | Hōki Yasutsuna (伯耆安綱) | One of the Five Swords under Heaven (天下五剣), legendary sword with which Minamoto no Yorimitsu killed the boy-faced oni Shuten-dōji (酒呑童子) living near Mount Oe. Presented to Oda Nobunaga by the Ashikaga family subsequently in possession of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, curvature: 2.7 cm (1.1 in) | mid Heian period, 10th–11th century | 80.0 cm (31.5 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

Saikaidō (Chikuzen, Chikugo, Bungo Province)

Through rich cultural exchange with China and Korea facilitated by the proximity to the continent, iron manufacture had been practiced on Kyūshū (Saikaidō) since earliest times. Swordsmiths were active from the Heian period onwards.[126][137] Initially the Yamato school's influence is evident all over the island.[137] However, distance from other swordmaking centers such as Yamato or Yamashiro caused the workmanship to remain static as smiths maintained old traditions and shunned innovations.[137] Kyūshū blades, therefore, demonstrate a classic workmanship.[138] The old Kyūshū smiths are represented by Bungo Yukihira from Bungo Province, the Miike school active in Chikugo Province and the Naminohira school of Satsuma Province.[138] Two old blades, one by Miike Mitsuyo and the other by Bungo Yukihira, and five later blades from the 14th century, have been designated as national treasures from Kyūshū. They originate from three provinces: Chikugo, Chikuzen, and Bungo. Generally Kyūshū blades are characterized by a sugata that looks old having a wide shinogi. The jihada is mokume-hada that tends to masame-hada or becomes ayasugi-hada.[j 57] The jigana is soft and there are ji-nie and chikei present. The hamon is small midare made up of nie and based on suguha. The edge of the hamon starts just above the hamachi.[j 58]

The work of Saemon Saburo Yasuyoshi (or Sa, Samonji, Ō-Sa) is much more sophisticated than that of other Kyūshū smiths.[139] As a student of Masamune he was influenced by the Sōshū tradition which is evident in his blades.[139] Sa was active from the end of the Kamakura period to the early Nanboku-chō period and was the founder of the Samonji school in Chikuzen Province to which also Yukihiro belonged.[139] He produced mainly tantō and a few extant tachi.[139] The Samonji school had a great influence during the Nanboku-chō period.[139] Stylistically Ō-Sa's sugata is typical for the end of the Kamakura period with a thick kasane, slightly large kissaki and tantō that are unusually short, about 24 cm (9.4 in).[139]

| Tachi[83][140] | Chikushū jū Sa (筑州住左) | Samonji (左文字) (Saemon Saburo Yasuyoshi)* | Only extant signed tachi of Samonji; also known as Kōsetsu Samonji (江雪左文字) since it was the favourite sword of Itabeoka Kōsetsu-sai (板部岡江雪斎) from the Late Hōjō clan, a retainer under Tokugawa Ieyasu; subsequently in the possession of Tokugawa Ieyasu and Tokugawa Yorinobu | early Nanboku-chō period, 14th century, around Kemmu and Ryakuō eras (1334–1342) | 78.1 cm (30.7 in) | Private (Komatsu Yasuhiro Industries), Hiroshima |

| Tantō | Chikushū jū Sa (筑州住左) | Samonji (左文字) (Saemon Saburo Yasuyoshi)* | — |

early Nanboku-chō period, 14th century, around Kemmu and Ryakuō eras (1334–1342) | 23.6 cm (9.3 in) | Private, Tokyo |

| Tachi or Ōtenta (大典太)#[28][59][141] | Work of Mitsuyo (光世作 Mitsuyo-saku) | Miike Mitsuyo (三池光世) (Tenta) | One of the Five Swords under Heaven (天下五剣), named (Ōtenta=Great Tenta) for its magnificent dignified sugata; curvature 2.7 cm (1.1 in) | Heian period, 11th century, around Jōhō era (1074–1077) | 66.1 cm (26.0 in) | Maeda Ikutokukai, Tokyo |

| Tachi or Kokin Denju no Tachi (古今伝授の太刀)#[142] | Work of Yukihira from Bungo Province (豊後国行平作 Bungo no kuni Yukihira-saku) | Yukihira (行平) | The sword was presented to the poet Karasumaru Mitsuhiro during the Siege of Tanabe, when Hosokawa Fujitaka initiated him in the Kokin Denju (secrets of Kokin Wakashū); later in the Shōwa period, the sword returned to the possession of the Hosokawa clan; curvature: 2.8 cm (1.1 in) | Kamakura period, around 1200 | 80 cm (31 in) | Eisei Bunko Museum, Tokyo |

| Ōdachi[143] | Unsigned | attributed to Bungo Tomoyuki (豊後友行) | Favourite sword of Ōmori Hikoshichi (大森彦七) and offered to Ōyamazumi Shrine by his grandchild Ōmori Naoji (大森直治) in 1470; curvature 5.4 cm (2.1 in) | Nanboku-chō period, 14th century | 180 cm (71 in) | Ōyamazumi Shrine, Imabari, Ehime |

| Tantō[144] | Chikushū jū Yukihiro (筑州住行弘) | Yukihiro (行弘) | Width (mihaba) 2.2 cm (0.87 in), thickness (kasane) 0.6 cm (0.24 in) | Nanboku-chō period, August 1350 | 23.5 cm (9.3 in) | Tsuchiura City Museum, Tsuchiura, Ibaraki |

| Tantō[83] | Sa (左) | Samonji (左文字) (Saemon Saburo Yasuyoshi)* | One of the favourite blades of Toyotomi Hideyoshi; handed down in the Kishū-Tokugawa family | early Nanboku-chō period, 14th century, around Kemmu and Ryakuō eras (1334–1342) | 23.6 cm (9.3 in) | Private, Hiroshima |

Sword mountings

For protection and preservation, a polished Japanese sword needs a scabbard.[145] A fully mounted scabbard (koshirae) may consist of a lacquered body, a taped hilt, a sword guard (tsuba) and decorative metal fittings.[145] Though the original purpose was to protect a sword from damage, from early times on Japanese sword mountings became a status symbol and were used to add dignity.[146] Starting in the Heian period, a sharp distinction was made between swords designed for use in battle and those for ceremonial use.[147] Tachi long swords were worn edge down suspended by two cords or chains from the waist belt. The cords were attached to two eyelets on the scabbard.[148]

Decorative sword mountings of the kazari-tachi type carried on the tradition of ancient straight Chinese style tachi and were used by nobles at court ceremonies until the Muromachi period. They contained a very narrow crude unsharpened blade. Two mountain-shaped metal fittings were provided to attach the straps; the scabbard between was covered by a (tube) fitting. The hilt was covered with ray skin and the scabbard typically decorated in maki-e or mother of pearl.[147]

Another type of mounting that became fashionable around the mid-Heian period is the kenukigata, or hair-tweezer style, named for the characteristically shaped hilt, which is pierced along the center. In this style, the hilt is fitted with an ornamental border and did not contain any wooden covering. Like kazari-tachi, swords with this mounting were used for ceremonial purposes but also in warfare, as an example held at Ise Grand Shrine shows.[149]

From the end of the Heian and into the Kamakura period, hyōgo-gusari[nb 21] were fashionable mountings for tachi. Along the edge of both the scabbard and the hilt they were decorated with a long ornamental border. They were originally designed for use in battle and worn by high-ranking generals together with armour; but in the Kamakura period they were made due to their gorgeous appearance exclusively for the dedication at temples and Shinto shrines. The corresponding blades from that time are unusable.[150]

During the Kamakura and Muromachi period, samurai wore a short sword known as koshigatana in addition to the long tachi. Koshigatana were stuck directly into the belt in the same way as later the katana and uchigatana.[148] They had a mounting without a guard (tsuba). The corresponding style is known as aikuchi ("fitting mouth") as the mouth of the scabbard meets the hilt directly without intervening guard.[151]

| Tachi[152][153] | Kazari-tachi[nb 22] | Heian period, 12th century | Metal fittings decorated with a chrysanthemum pattern in gilt openwork carved in high relief over a silver ground, scabbard decorated with long-tailed birds in mother of pearl inlay on nashiji lacquer ground. Its slight curvature represents a departure from Chinese prototypes. | The mounting was handed down in the Hirohashi family (廣橋家). | — |

103.3 cm (40.7 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[154][155] | Hyōgo-gusari[nb 23] | Kamakura period, 13th century | Scabbard decorated with birds, nashiji lacquer, mother of pearl inlay, gold fittings; blade signed ichi (一) | Blade made by Ichimonji; also known as Uesugi Tachi (上杉太刀) as it was handed down in the Uesugi clan; later offered to Mishima Taisha and presented to the Imperial Household in the Meiji period | 76.06 cm (29.94 in) | 105.4 cm (41.5 in) | Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Tachi[76][156] | Hyōgo-gusari[nb 23] | Nanboku-chō period, 1385 | Wood, silver, gold, and copper; blade unsigned | Offered to the shrine by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu | — |

126 cm (50 in) | Kasuga-taisha, Nara, Nara |

| Tachi[149][156] | Kenukigata[nb 24] | Heian period | Scabbard in mother of pearl design on gold ground of sparrows in a bamboo thicket | Blade is rusted in and cannot be withdrawn | — |

— |

Kasuga-taisha, Nara, Nara |

| Uchigatana[nb 25] | Nanboku-chō period, 1385 | Blade unsigned | Made by Hishi (菱) | — |

73 cm (29 in) | Kasuga-taisha, Nara, Nara | |

| Tachi | Kenukigata[nb 24] | Kamakura period | Blade unsigned; ikakeji[nb 26] and guardian dog design | — |

— |

— |

Kasuga-taisha, Nara, Nara |

| Tachi[157] | Hyōgo-gusari[nb 23] | Kamakura period | Blade unsigned; ikakeji[nb 26] and sleeping beauty lacquer design | — |

— |

— |

Kasuga-taisha, Nara, Nara |

| Tachi | Hyōgo-gusari[nb 23] | Kamakura period | Blade unsigned; ikakeji[nb 26] and sleeping beauty design | — |

— |

— |

Kasuga-taisha, Nara, Nara |

| Tachi[150][158] | unique[nb 27] | late Heian period, 12th century | Long and narrow thin sheets of silver-plated copper are wreathed around the scabbard and handle (hirumaki) | No blade present | — |

104.1 cm (41.0 in) | Niutsuhime Shrine, Katsuragi, Wakayama; custody of the Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo |

| Koshigatana[nb 28][151][159] | Aikuchi | Muromachi period | Blade with a signature Made by Tomonari (友成作 Tomonari-saku) (from the Ko-Bizen school); nashiji lacquer and paulownia design in mother of pearl inlay | Blade had been damaged by fire and subsequently retempered; said to have belonged to Ashikaga Takauji | 20.3 cm (8.0 in) | 37.2 cm (14.6 in) | Itsukushima Shrine, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima |

| Koshigatana[160] | Aikuchi | Kamakura period | Blade unsigned; hilt and scabbard covered with gold nashiji, chrysanthemum design in shakudō on hilt | Blade attributed to Taima (当麻) | 26.5 cm (10.4 in) | 30.8 cm (12.1 in) | Mōri Museum, Hōfu, Yamaguchi |

| Tachi[161] | Hyōgo-gusari[nb 23] | Kamakura period, 14th century | Blade unsigned; handle covered with white shark skin, nanako-ji (small circular lumps in the surface of the fitting), gilt openwork of tree peony arabesque carved in high relief, scabbard with line engraving of peonies on gilt bronze ground, guard with a wide ornamental border of Flowering Quince, gilt bronze metal fittings with peony design | Considered to be an offering to the shrine by Prince Moriyoshi | 60.9 cm (24.0 in) | 97 cm (38 in) | Ōyamazumi Shrine, Imabari, Ehime |

See also

- Japanese sword

- Japanese sword mountings

- Glossary of Japanese swords

- Nara Research Institute for Cultural Properties

- Tokyo Research Institute for Cultural Properties

- Independent Administrative Institution National Museum

Notes

- General

- ↑ These tachi of the ancient sword (jokotō) period should not be confused with later tachi of the old sword (kotō) period. The former, spelled 大刀, are Chinese style straight chokutō, while the latter, spelled 太刀, are curved blades.

- ↑ According to the Showa Mei Zukushi (1312–1317), one of the oldest extant lists of swordsmiths, the goban kaji were Norimune, Nobufusa, Muneyoshi, Sukemune, Yukikuni, Sukenari, Sukenobu or Sukechika from Bizen province; Sadatsugu, Tsunetsugu, Tsuguie from Bitchū province and Kuniyasu, Kunitomo from Yamashiro province.

- ↑ Many of these were shortened into katana during the Momoyama period.

- ↑ Other swords from that period have been designated as National Treasures as part of excavated sets of items in the category archaeological materials.

- ↑ Sometimes misspelled as Komura Shrine

- ↑ A karabitsu (唐櫃) chest is attached to the nomination.

- ↑ A black lacquer mounting (黒漆宝剣拵 kuro urushi hōken koshirae) is attached to the nomination.

- ↑ Oldest of five Yamato schools, named after Senjuin temple

- ↑ Named after Taima-dera

- ↑ Named after Tengai-mon, a gate of Tōdai-ji

- ↑ Named after a family name, located at Takaichi

- 1 2 3 Name as listed in the Kyōhō Meibutsu-chō (享保名物帳)

- ↑ There were likely many other founders whose works do not exist anymore.

- ↑ Sometimes Masatsune is also credited with the founding.

- ↑ With some exceptions such as the Ōkanehira by Kanehira

- 1 2 The Tomonari who forged the swords signed Tomonari saku and Bizen no kuni Tomonari tsukuru are two different smiths

- ↑ A thread-wrapped slung-sword mounting (糸巻太刀拵 ito maki no tachi koshirae) with gold nashiji lacquer and scattered hollyhock insignia from the 17th century Edo period is attached to the nomination. The mounting is made of wood, lacquer, shakudō, gold, and silk. Its overall length is 112.1 cm (44.1 in).

- ↑ A black-lacquered short sword mounting (小サ刀拵 chiisagatana koshirae) for a tantō with a tsuba (sword guard) is attached to the nomination. It dates to the 16th century Muromachi period and is made of wood, lacquer, rayskin, leather, shakudō, gold, silver and silk. Its overall length is 46.2 cm (18.2 in).

- ↑ A thread-wrapped slung-sword mounting (糸巻太刀拵 ito maki no tachi koshirae) with gold nashiji lacquer from the late 16th century Momoyama period is attached to the nomination. The mounting is made of wood, lacquer, shakudō, gold, and silk. Its overall length is 109 cm (43 in).

- ↑ This Yasutsugu is not the one in the list of swords.

- ↑ "Hyōgo" was the name for the weapon arsenal at court and "gusari" meaning chains, refers to the straps which were made in a special woven technique, with which the sword was hung from the belt.

- ↑ Kazari-tachi: Large elaborately decorated ceremonial sword worn by eighth century court nobles

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hyōgo-gusari: a sword hung from the obi by a chain

- 1 2 Kenukigata: a hilt whose center is pierced resembling hair tweezers (jap.: kenukigata)

- ↑ Attached to the nomination is a cedar box with an ink inscription on the underside of the lid: Offered by Hamuro Nagamune on January 22, 1385 (至徳二年正月二十二日葉 室 長宗奉納 shitoku ninen shōgatsu nijūninichi Hamuro Nagamune hōnō)

- 1 2 3 Ikakeji: A makie technique in which gold or silver powder is sprinkled densely over the lacquered ground

- ↑ This is the only extant example of this kind of mounting. It does not have a special name.

- ↑ A gold or silver lacquer box is attached to the nomination.

- Jargon

- ↑ overall shape of the blade

- ↑ curvature (sori) of the blade in which the center of the curve lies roughly in the center of the blade resembling the horizontal bar of torii

- ↑ ridge running along the side of the sword, generally closer to the back than the cutting edge

- ↑ fan-shaped blade point

- ↑ visible surface pattern of the steel resulting from hammering and folding during the construction

- ↑ straight surface grain pattern (jihada)

- ↑ border between the tempered part of the cutting edge and the untempered part of the rest of the sword; the temper-line

- ↑ straight temper line (hamon)

- ↑ small distinct crystalline particles due to martensite, austenite, pearlite or troostite that appear like twinkling stars

- ↑ temper line (hamon) of the blade point (kissaki)

- ↑ temper line (hamon) that forms a small circle as it turns back towards the back side of the blade in the point area (kissaki).

- ↑ blade width

- ↑ blade thickness

- ↑ tapering of the blade from the base to the point

- ↑ surface grain pattern (jihada) of scattered irregular ovals resembling wood grain

- ↑ curvature (sori) of the blade with the center of the curve lying near or inside of the tang (nakago)

- ↑ nie that appears in the ji

- ↑ black gleaming lines of nie that appear in the ji

- ↑ surface grain pattern (jihada) of small ovals and circles resembling the burl-grain in wood

- ↑ indistinguishable crystalline particles due to martensite, austenite, pearlite or troostite that appear together like a wash of stars

- ↑ an irregular temper line (hamon) pattern resembling cloves, with a round upper part and a narrow constricted lower part

- 1 2 patterns and shapes such as lines, streaks, dots and hazy reflections that appear in addition to the grain pattern (jihada) and the temper line (hamon) on the surface of the steel and are a result of sword polishing

- ↑ generally used to refer to the material of the blade

- ↑ spot or spots where nie is concentrated on the ji

- ↑ curvature of the blade

- ↑ a tempering (metallurgy) spot within the ji not connected to the main temper line (hamon)

- ↑ temper line (hamon) with tempering marks visible around the ridge and near the edge of the blade

- ↑ pair of parallel grooves running partway up the blade resembling chopsticks

- ↑ a short, stubby blade point (kissaki)

- ↑ curvature of the blade with a slight curve toward the cutting edge

- ↑ surface grain pattern (jihada) resembling the flesh of a sliced pear (jap. nashi)

- ↑ area between the ridge (shinogi) and the temper line (hamon)

- ↑ a wave-like outline of the temper line (hamon) made up of similarly sized semicircles.

- 1 2 an irregular temper line (hamon)

- ↑ marks in the temper line (hamon) that resemble the pattern left behind by a broom sweeping over sand

- ↑ short straight thin radiant black line of higher carbon content that appears in the temper-line (hamon).

- ↑ misty reflection on the ji or shinogiji usually made of softer steel

- ↑ multiple overlapping clove shaped chōji midare patterns

- ↑ a variation of the chōji midare pattern with the peaks resembling tadpoles

- ↑ a gunome pattern with a straight top and an overall slant

- ↑ irregular temper line (midareba) that continues into the point (kissaki)

- ↑ part of the temper line (hamon) that extends from the tip of the bōshi to the back ridge (mune)

- ↑ without turn-back (kaeri); a bōshi that continues directly to the back ridge (mune)

- ↑ bōshi seen in the works of the three swordsmiths: Osafune Nagamitsu, Kagemitsu and Sanenaga: hamon continues as straight line inside the point (kissaki) area running towards the tip of the blade. Just before reaching the tip, the bōshi turns in a small circle a short distance to the back ridge (mune) remaining inside the point area

- ↑ misty spots in the temper line (hamon) resulting from repeated grinding or faulty tempering

- ↑ the cutting edge (ha) of the blade point (kissaki)

- ↑ ridge of the back edge (mune), the back ridge

- ↑ surface grain pattern (jihada) resembling the bark of a pine tree

- ↑ a large grain pattern (jihada)

- ↑ gently waving temper line (hamon)

- ↑ a fully tempered point area (kissaki) because the temper line (hamon) turns back before reaching the point

- ↑ a bōshi which turns back in a straight horizontal line with a short kaeri

- ↑ thin line that runs across the temper line (hamon) to the cutting edge (ha)

- ↑ distinctly visible mokume-hada (surface grain pattern of small ovals and circles resembling the burl-grain in wood) with a clearer steel than in similar but coarser patterns

- ↑ plain dark spots on the ji that differ considerably from the surface pattern in both color and grain

- ↑ activity (hataraki) in the temper line (hamon) that resembles fallen leaves or tiny footprints

- ↑ regular wavy surface grain pattern (jihada)

- ↑ notch in the cutting edge (ha), dividing the blade proper from the tang (nakago)

References

- ↑ Coaldrake, William Howard (2002) [1996]. Architecture and authority in Japan. London, New York: Routledge. p. 248. ISBN 0-415-05754-X. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ↑ Enders & Gutschow 1998, p. 12

- ↑ "Cultural Properties for Future Generations" (PDF). Tokyo, Japan: Agency for Cultural Affairs, Cultural Properties Department. March 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- 1 2 The Agency for Cultural Affairs (2008-11-01). 国指定文化財 データベース (in Japanese). Database of National Cultural Properties. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ Noma 2003, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Kleiner 2008, p. 208

- ↑ Shiveley, McCullough & Hall 1993, pp. 80–107

- 1 2 Murphy, Declan. "Yayoi Culture". Yamasa Institute. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- 1 2 3 Nagayama 1998, p. 2

- ↑ Keally, Charles T. (2006-06-03). "Yayoi Culture". Japanese Archaeology. Charles T. Keally. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- 1 2 3 Yumoto 1979, p. 27

- ↑ Satō & Earle 1983, p. 28

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nagayama 1998, p. 12

- 1 2 3 4 Nagayama 1998, p. 13

- 1 2 Yumoto 1979, p. 28

- 1 2 Satō & Earle 1983, p. 46

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Yumoto 1979, p. 29

- 1 2 Nagayama 1998, p. 15

- 1 2 Nagayama 1998, p. 16

- ↑ Satō & Earle 1983, p. 47