Liquid

| Continuum mechanics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

Laws

|

||||

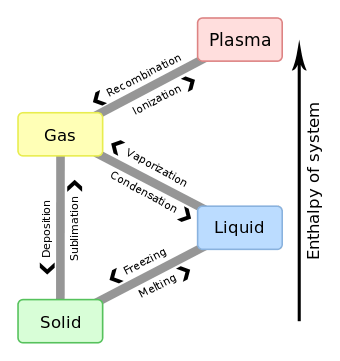

A liquid is a nearly incompressible fluid that conforms to the shape of its container but retains a (nearly) constant volume independent of pressure. As such, it is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, gas, and plasma), and is the only state with a definite volume but no fixed shape. A liquid is made up of tiny vibrating particles of matter, such as atoms, held together by intermolecular bonds. Water is, by far, the most common liquid on Earth. Like a gas, a liquid is able to flow and take the shape of a container. Most liquids resist compression, although others can be compressed. Unlike a gas, a liquid does not disperse to fill every space of a container, and maintains a fairly constant density. A distinctive property of the liquid state is surface tension, leading to wetting phenomena.

The density of a liquid is usually close to that of a solid, and much higher than in a gas. Therefore, liquid and solid are both termed condensed matter. On the other hand, as liquids and gases share the ability to flow, they are both called fluids. Although liquid water is abundant on Earth, this state of matter is actually the least common in the known universe, because liquids require a relatively narrow temperature/pressure range to exist. Most known matter in the universe is in gaseous form (with traces of detectable solid matter) as interstellar clouds or in plasma form within stars.

Introduction

Liquid is one of the four primary states of matter, with the others being solid, gas and plasma. A liquid is a fluid. Unlike a solid, the molecules in a liquid have a much greater freedom to move. The forces that bind the molecules together in a solid are only temporary in a liquid, allowing a liquid to flow while a solid remains rigid.

A liquid, like a gas, displays the properties of a fluid. A liquid can flow, assume the shape of a container, and, if placed in a sealed container, will distribute applied pressure evenly to every surface in the container. If you place the liquid in a bag, you can squeeze it into any shape you want. Unlike a gas, a liquid may not always mix readily with another liquid, will not always fill every space in the container, forming its own surface, and will not compress significantly, except under extremely high pressures. These properties make a liquid suitable for applications such as hydraulics.

Liquid particles are bound firmly but not rigidly. They are able to move around one another freely, resulting in a limited degree of particle mobility. As the temperature increases, the increased vibrations of the molecules causes distances between the molecules to increase. When a liquid reaches its boiling point, the cohesive forces that bind the molecules closely together break, and the liquid changes to its gaseous state (unless superheating occurs). If the temperature is decreased, the distances between the molecules become smaller. When the liquid reaches its freezing point the molecules will usually lock into a very specific order, called crystallizing, and the bonds between them become more rigid, changing the liquid into its solid state (unless supercooling occurs).

Examples

Only two elements are liquid at standard conditions for temperature and pressure: mercury and bromine. Four more elements have melting points slightly above room temperature: francium, caesium, gallium and rubidium.[1] Metal alloys that are liquid at room temperature include NaK, a sodium-potassium metal alloy, galinstan, a fusible alloy liquid, and some amalgams (alloys involving mercury).

Pure substances that are liquid under normal conditions include water, ethanol and many other organic solvents. Liquid water is of vital importance in chemistry and biology; it is believed to be a necessity for the existence of life.

Inorganic liquids include water, magma, inorganic nonaqueous solvents and many acids.

Important everyday liquids include aqueous solutions like household bleach, other mixtures of different substances such as mineral oil and gasoline, emulsions like vinaigrette or mayonnaise, suspensions like blood, and colloids like paint and milk.

Many gases can be liquefied by cooling, producing liquids such as liquid oxygen, liquid nitrogen, liquid hydrogen and liquid helium. Not all gases can be liquified at atmospheric pressure, for example carbon dioxide can only be liquified at pressures above 5.1 atm.

Some materials cannot be classified within the classical three states of matter; they possess solid-like and liquid-like properties. Examples include liquid crystals, used in LCD displays, and biological membranes.

Applications

Liquids have a variety of uses, as lubricants, solvents, and coolants. In hydraulic systems, liquid is used to transmit power.

In tribology, liquids are studied for their properties as lubricants. Lubricants such as oil are chosen for viscosity and flow characteristics that are suitable throughout the operating temperature range of the component. Oils are often used in engines, gear boxes, metalworking, and hydraulic systems for their good lubrication properties.[2]

Many liquids are used as solvents, to dissolve other liquids or solids. Solutions are found in a wide variety of applications, including paints, sealants, and adhesives. Naphtha and acetone are used frequently in industry to clean oil, grease, and tar from parts and machinery. Body fluids are water based solutions.

Surfactants are commonly found in soaps and detergents. Solvents like alcohol are often used as antimicrobials. They are found in cosmetics, inks, and liquid dye lasers. They are used in the food industry, in processes such as the extraction of vegetable oil.[3]

Liquids tend to have better thermal conductivity than gases, and the ability to flow makes a liquid suitable for removing excess heat from mechanical components. The heat can be removed by channeling the liquid through a heat exchanger, such as a radiator, or the heat can be removed with the liquid during evaporation.[4] Water or glycol coolants are used to keep engines from overheating.[5] The coolants used in nuclear reactors include water or liquid metals, such as sodium or bismuth.[6] Liquid propellant films are used to cool the thrust chambers of rockets.[7] In machining, water and oils are used to remove the excess heat generated, which can quickly ruin both the work piece and the tooling. During perspiration, sweat removes heat from the human body by evaporating. In the heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning industry (HVAC), liquids such as water are used to transfer heat from one area to another.[8]

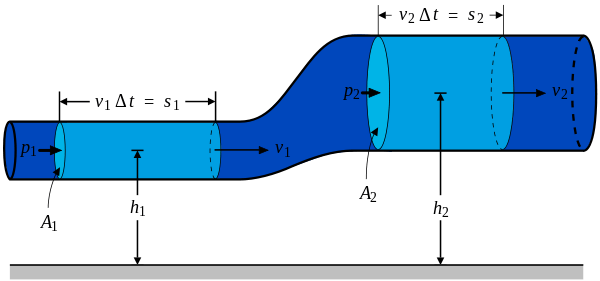

Liquid is the primary component of hydraulic systems, which take advantage of Pascal's law to provide fluid power. Devices such as pumps and waterwheels have been used to change liquid motion into mechanical work since ancient times. Oils are forced through hydraulic pumps, which transmit this force to hydraulic cylinders. Hydraulics can be found in many applications, such as automotive brakes and transmissions, heavy equipment, and airplane control systems. Various hydraulic presses are used extensively in repair and manufacturing, for lifting, pressing, clamping and forming.[9]

Liquids are sometimes used in measuring devices. A thermometer often uses the thermal expansion of liquids, such as mercury, combined with their ability to flow to indicate temperature. A manometer uses the weight of the liquid to indicate air pressure.[10]

Mechanical properties

Volume

Quantities of liquids are commonly measured in units of volume. These include the SI unit cubic metre (m3) and its divisions, in particular the cubic decimeter, more commonly called the litre (1 dm3 = 1 L = 0.001 m3), and the cubic centimetre, also called millilitre (1 cm3 = 1 mL = 0.001 L = 10−6 m3).

The volume of a quantity of liquid is fixed by its temperature and pressure. Liquids generally expand when heated, and contract when cooled. Water between 0 °C and 4 °C is a notable exception. Liquids have little compressibility. Water, for example, will compress by only 46.4 parts per million for every unit increase in atmospheric pressure (bar).[11] At around 4000 bar (58,000 psi) of pressure, at room temperature, water only experiences an 11% decrease in volume.[12] In the study of fluid dynamics, liquids are often treated as incompressible, especially when studying incompressible flow. This incompressible nature makes a liquid suitable for transmitting hydraulic power, because very little of the energy is lost in the form of compression.[12] However, the very slight compressibility does lead to other phenomena. The banging of pipes, called water hammer, occurs when a valve is suddenly closed, creating a huge pressure-spike at the valve that travels backward through the system at just under the speed of sound. Another phenomenon caused by liquid's incompressibility is cavitation. Because liquids have little elasticity they can literally be pulled apart in areas of high turbulence or a dramatic change in direction, such as the trailing edge of a boat propeller or a sharp corner in a pipe. A liquid in an area of low pressure (vacuum) vaporizes and forms bubbles, which then collapse as they enter high pressure areas. This causes liquid to fill the cavities left by the bubbles with tremendous localized force, eroding any adjacent solid surface.[13]

Pressure and buoyancy

In a gravitational field, liquids exert pressure on the sides of a container as well as on anything within the liquid itself. This pressure is transmitted in all directions and increases with depth. If a liquid is at rest in a uniform gravitational field, the pressure, p, at any depth, z, is given by

where:

- is the density of the liquid (assumed constant)

- is the gravitational acceleration.

Note that this formula assumes that the pressure at the free surface is zero, and that surface tension effects may be neglected.

Objects immersed in liquids are subject to the phenomenon of buoyancy. (Buoyancy is also observed in other fluids, but is especially strong in liquids due to their high density.)

Surfaces

Unless the volume of a liquid exactly matches the volume of its container, one or more surfaces are observed. The surface of a liquid behaves like an elastic membrane in which surface tension appears, allowing the formation of drops and bubbles. Surface waves, capillary action, wetting, and ripples are other consequences of surface tension. In a confined liquid, defined by geometric constraints on a nanoscopic scale, most molecules sense some surface effects, which can result in physical properties grossly deviating from those of the bulk liquid.

Free surface

A free surface is the surface of a fluid that is subject to both zero perpendicular normal stress and parallel shear stress, such as the boundary between, e.g., liquid water and the air in the Earth's atmosphere.

Level

The liquid level (as in, e.g., water level) is the height associated with the liquid free surface, especially when it's the top-most surface. It may be measured with a level sensor.

Flow

Viscosity measures the resistance of a liquid which is being deformed by either shear stress or extensional stress.

When a liquid is supercooled towards the glass transition, the viscosity increases dramatically. The liquid then becomes a viscoelastic medium that shows both the elasticity of a solid and the fluidity of a liquid, depending on the time scale of observation or on the frequency of perturbation.

Sound propagation

The speed of sound in a fluid is given by where K is the bulk modulus of the fluid, and ρ the density. To give a typical value, in fresh water c=1497 m/s at 25 °C.

Thermodynamics

Phase transitions

At a temperature below the boiling point, any matter in liquid form will evaporate until the condensation of gas above reach an equilibrium. At this point the gas will condense at the same rate as the liquid evaporates. Thus, a liquid cannot exist permanently if the evaporated liquid is continually removed. A liquid at its boiling point will evaporate more quickly than the gas can condense at the current pressure. A liquid at or above its boiling point will normally boil, though superheating can prevent this in certain circumstances.

At a temperature below the freezing point, a liquid will tend to crystallize, changing to its solid form. Unlike the transition to gas, there is no equilibrium at this transition under constant pressure, so unless supercooling occurs, the liquid will eventually completely crystallize. Note that this is only true under constant pressure, so e.g. water and ice in a closed, strong container might reach an equilibrium where both phases coexist. For the opposite transition from solid to liquid, see melting.

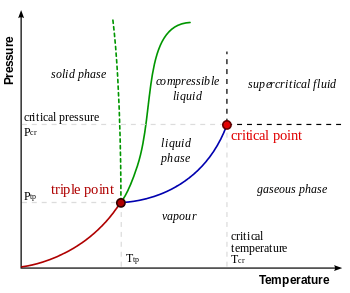

Liquids in space

The phase diagram explains why liquids do not exist in space or any other vacuum. Since the pressure is zero (except on surfaces or interiors of planets and moons) water and other liquids exposed to space will either immediately boil or freeze depending on the temperature. In regions of space near the earth, water will freeze if the sun is not shining directly on it and vapourize (sublime) as soon as it is in sunlight. If water exists as ice on the moon, it can only exist in shadowed holes where the sun never shines and where the surrounding rock doesn't heat it up too much. At some point near the orbit of Saturn, the light from the sun is too faint to sublime ice to water vapour. This is evident from the longevity of the ice that composes Saturn's rings.

Solutions

Liquids can display immiscibility. The most familiar mixture of two immiscible liquids in everyday life is the vegetable oil and water in Italian salad dressing. A familiar set of miscible liquids is water and alcohol. Liquid components in a mixture can often be separated from one another via fractional distillation.

Microscopic properties

Static structure factor

In a liquid, atoms do not form a crystalline lattice, nor do they show any other form of long-range order. This is evidenced by the absence of Bragg peaks in X-ray and neutron diffraction. Under normal conditions, the diffraction pattern has circular symmetry, expressing the isotropy of the liquid. In radial direction, the diffraction intensity smoothly oscillates. This is usually described by the static structure factor S(q), with wavenumber q=(4π/λ)sinθ given by the wavelength λ of the probe (photon or neutron) and the Bragg angle θ. The oscillations of S(q) express the near order of the liquid, i.e. the correlations between an atom and a few shells of nearest, second nearest, ... neighbors.

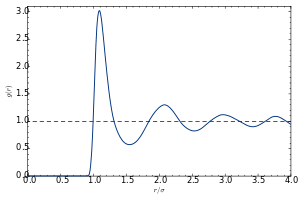

A more intuitive description of these correlations is given by the radial distribution function g(r), which is basically the Fourier transform of S(q). It represents a spatial average of a temporal snapshot of pair correlations in the liquid.

Sound dispersion and structural relaxation

The above expression for the sound velocity contains the bulk modulus K. If K is frequency independent then the liquid behaves as a linear medium, so that sound propagates without dissipation and without mode coupling. In reality, any liquid shows some dispersion: with increasing frequency, K crosses over from the low-frequency, liquid-like limit to the high-frequency, solid-like limit . In normal liquids, most of this cross over takes place at frequencies between GHz and THz, sometimes called hypersound.

At sub-GHz frequencies, a normal liquid cannot sustain shear waves: the zero-frequency limit of the shear modulus is . This is sometimes seen as the defining property of a liquid.[14][15] However, just as the bulk modulus K, the shear modulus G is frequency dependent, and at hypersound frequencies it shows a similar cross over from the liquid-like limit to a solid-like, non-zero limit .

According to the Kramers-Kronig relation, the dispersion in the sound velocity (given by the real part of K or G) goes along with a maximum in the sound attenuation (dissipation, given by the imaginary part of K or G). According to linear response theory, the Fourier transform of K or G describes how the system returns to equilibrium after an external perturbation; for this reason, the dispersion step in the GHz..THz region is also called structural relaxation. According to the fluctuation-dissipation theorem, relaxation towards equilibrium is intimately connected to fluctuations in equilibrium. The density fluctuations associated with sound waves can be experimentally observed by Brillouin scattering.

On supercooling a liquid towards the glass transition, the crossover from liquid-like to solid-like response moves from GHz to MHz, kHz, Hz, ...; equivalently, the characteristic time of structural relaxation increases from ns to μs, ms, s, ... This is the microscopic explanation for the above-mentioned viscoelastic behaviour of glass-forming liquids.

Effects of association

The mechanisms of atomic/molecular diffusion (or particle displacement) in solids are closely related to the mechanisms of viscous flow and solidification in liquid materials. Descriptions of viscosity in terms of molecular "free space" within the liquid[16] were modified as needed in order to account for liquids whose molecules are known to be "associated" in the liquid state at ordinary temperatures. When various molecules combine together to form an associated molecule, they enclose within a semi-rigid system a certain amount of space which before was available as free space for mobile molecules. Thus, increase in viscosity upon cooling due to the tendency of most substances to become associated on cooling.[17]

Similar arguments could be used to describe the effects of pressure on viscosity, where it may be assumed that the viscosity is chiefly a function of the volume for liquids with a finite compressibility. An increasing viscosity with rise of pressure is therefore expected. In addition, if the volume is expanded by heat but reduced again by pressure, the viscosity remains the same.

The local tendency to orientation of molecules in small groups lends the liquid (as referred to previously) a certain degree of association. This association results in a considerable "internal pressure" within a liquid, which is due almost entirely to those molecules which, on account of their temporary low velocities (following the Maxwell distribution) have coalesced with other molecules. The internal pressure between several such molecules might correspond to that between a group of molecules in the solid form.

References

- ↑ Theodore Gray, The Elements: A Visual Exploration of Every Known Atom in the Universe New York: Workman Publishing, 2009 p. 127 ISBN 1-57912-814-9

- ↑ Theo Mang, Wilfried Dressel ’’Lubricants and lubrication’’, Wiley-VCH 2007 ISBN 3-527-31497-0

- ↑ George Wypych ’’Handbook of solvents’’ William Andrew Publishing 2001 pp. 847–881 ISBN 1-895198-24-0

- ↑ N. B. Vargaftik ’’Handbook of thermal conductivity of liquids and gases’’ CRC Press 1994 ISBN 0-8493-9345-0

- ↑ Jack Erjavec ’’Automotive technology: a systems approach’’ Delmar Learning 2000 p. 309 ISBN 1-4018-4831-1

- ↑ Gerald Wendt ’’The prospects of nuclear power and technology’’ D. Van Nostrand Company 1957 p. 266

- ↑ ’’Modern engineering for design of liquid-propellant rocket engines’’ by Dieter K. Huzel, David H. Huang – American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1992 p. 99 ISBN 1-56347-013-6

- ↑ Thomas E Mull ’’HVAC principles and applications manual’’ McGraw-Hill 1997 ISBN 0-07-044451-X

- ↑ R. Keith Mobley Fluid power dynamics Butterworth-Heinemann 2000 p. vii ISBN 0-7506-7174-2

- ↑ Bela G. Liptak ’’Instrument engineers’ handbook: process control’’ CRC Press 1999 p. 807 ISBN 0-8493-1081-4

- ↑ http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/tables/compress.html

- 1 2 Intelligent Energy Field Manufacturing: Interdisciplinary Process Innovations By Wenwu Zhang -- CRC Press 2011 Page 144

- ↑ Fluid Mechanics and Hydraulic Machines by S. C. Gupta -- Dorling-Kindersley 2006 Page 85

- ↑ Born, Max (1940). "On the stability of crystal lattices". Mathematical Proceedings. Cambridge Philosophical Society. 36 (2): 160–172. Bibcode:1940PCPS...36..160B. doi:10.1017/S0305004100017138.

- ↑ Born, Max (1939). "Thermodynamics of Crystals and Melting". Journal of Chemical Physics. 7 (8): 591–604. Bibcode:1939JChPh...7..591B. doi:10.1063/1.1750497.

- ↑ D.B. Macleod (1923). "On a relation between the viscosity of a liquid and its coefficient of expansion". Trans. Farad. Soc. 19: 6. doi:10.1039/tf9231900006.

- ↑ G.W Stewart (1930). "The Cybotactic (Molecular Group) Condition in Liquids; the Association of Molecules". Phys. Rev. 35 (7): 726. Bibcode:1930PhRv...35..726S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.35.726.