Linee

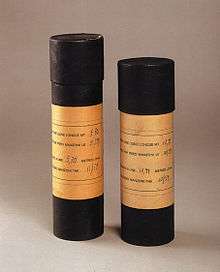

Linee (lines) is an artist's book by the Italian artist Piero Manzoni, created in 1959. Each work consists of a cardboard tube, a scroll of paper with a black line drawn down it, and a simple printed and autographed label. This label contains a brief description of the work, the work’s length, the artist’s name and the date it was created. Most of the lines were made between September and December 1959. 68 are known to have been made,[1] each with different length strips inside.

First public exhibition

The first public exhibition of the Linee was at Galleria Pozzetto Chiuso in Albissola Marina, between 18 and 24 August, occasion in which Lucio Fontana Buy the Linea m 9,48.[2] The second public presentation of the lines was at the inaugural exhibition of the Galleria Azimut, Milan, a space run by Enrico Castellani and Manzoni himself, between 4 and 24 December 1959. 11 lines were exhibited unopened on wooden plinths, whilst a twelfth strip was unrolled and attached directly to the entire length of one wall. The tubes were sold for between 25 & 80 thousand lire,[3] depending on their length, which ranged from 4m 89 to 33m 63. Manzoni seems to have changed his mind about the unveiling of the twelfth strip, as he wrote in May 1960 that the tubes ‘must not be opened.’[4] Despite this, the strips are still occasionally unrolled when exhibited.

Originally the lines, when bought, would become a personal act of unveiling by the buyer, not dissimilar to an individual reading a book. There are documentary photos by Manzoni recording one such opening. Uliano Lucas, a friend and occasional collaborator of Manzoni is shown unravelling one such line, to discover the text '15 Capo Linea' (Head Line) at the end.[5] Once the practice of demanding that the work remained hidden had been established, however, the tubes became objects that record an unseen artistic event, at a specific moment in time; what Duchamp called ‘a kind of rendezvous’.

The artistic act of drawing the lines becomes totally obscured, replaced by an imaginary idea of what they might look like, born witness by the labels on the tube, but not revealed. The works elevate the external text whilst diminishing the art object, implying that only the visualisation of the work in the mind’s eye is valid. This idea was to be taken further with his "Artist’s Shit", where the contents are unknowable without destroying the container, and reached its logical conclusion with the "Lines of Infinite Length", where the line only exists as a metaphysical speculation.

Although the Lines are hidden from view, their labels identify them as events that occurred at a particular time; they are like pieces of evidence bearing witness to the artist's activity. The object of our gaze is therefore not a finished product, but rather the remnant of an act that has transpired.[6]

"Lines of Exceptional Length" ("Linee dalla lunghezza eccezionale", 1960-1961)

There were three extra works that followed the original multiple; All were lines equal to or in excess of a kilometre long, and were contained in metal cylinders. The first, a 7,200 m line made in the presence of witnesses, was drawn on a rotary press at the Printing press for the newspaper Herning Avis, Denmark, on July 4, 1959.[7] The work was made with a bottle filled with ink with a stopper at the top. The continuous sheet was then placed inside a zinc cylinder covered in lead sheets. Two more lines of exceptional length were made on 24 July 1961, one 1,000 m long, the other 1,140 metres.

These were then placed in steel containers, and marked the beginnings of a series of cylinders Manzoni planned to leave in the principal cities of the world, which, when the lines were joined together, would be equal to the circumference of the world.[8] This work would remain unfinished at his death, 20 months later.

Other related works

Another related work on this theme are the "Linee di Lunghezza Infinita" of 1960 ("Lines of Infinite Length"), made of a carved piece of wood, closely resembling the original Linee, and similarly labelled, but citing the length of the strip contained inside as Infinite. Since the wood is solid, it cannot contain a strip inside, any more than if there were, it couldn’t be infinitely long. The piece takes ideas Manzoni had about works existing only in the viewers imagination to their logical conclusion; the work, in effect, is impossible, containing an impossible line, and therefore can only exist in the viewer’s mind.

Six were made before Manzoni’s death, although he printed and signed more labels, which have been used to complete the edition since his death.

The ‘disappearance of the artwork as literal object’, and the elevation of the text as central to the works meaning clearly anticipates the conceptual art movement of the late 1960s.

Manzoni also prepared a mock-up of three booklets, intended to be published as part of the avant-garde magazine Gorgona, Zagreb. One of these, "Table of Assessment #3", was a booklet featuring a continuous line running the length of the booklet. The work was never realised due to lack of funds.[9]

Influences

Rauschenberg’s Automobile Tire Print, 1951 is an obvious precedent, being a scroll containing a continuous (tyre) print, which can only be seen in sections. The work is also contemporaneous with Tinguely's "Cyclomatic", a big machine made of a roll of paper 11/2 km long, bicycle parts and an inkpad. When ridden by two cyclists, the work would scatter continuous bicycle tyre prints into the audience.[10] The work of Marcel Duchamp also provides a number of reference points, being concerned with the removal of the artist’s hand from the artwork, and attempting to negate any aesthetic decisions.

The sale of different "Lines" at different prices recalls Yves Klein’s "Proposition: Monochrome" exhibition in Milan, 1957, which Manzoni is known to have seen and been deeply affected by.[11] The lines of exceptional lengths are recalled in Martin Kippenberger's "Metro-Net", a series of subway entrances intended to be built into the ground of every major city in the world, metaphysically joining them. Like Manzoni, Kippenberger would die before more than a handful were completed.[12]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Piero Manzoni Catalog Generale, vol 1, Celant

- ↑ Pola, Francesca. Una visione internazionale. Piero Manzoni e Albisola. Electa, 2013.

- ↑ Corriere della Sera, Milan, 1959-12-16, quoted in Piero Manzoni, Catalog Raisoné, Battino & Palazzoli, p. 59

- ↑ Letter to Shozu Yamazaki, quoted in Piero Manzoni Catalogue Raisoné, Battino & Palazzoli, p. 85

- ↑ Piero Manzoni, Catalog Raisoné, Battino & Palazzoli, p61

- ↑ Piero Manzoni, Suzanne Cotter, Serpentine Gallery, 1998, p. 6

- ↑ Piero Manzoni Catalogue Raisoné, Battino & Palazzoli, p. 95

- ↑ Piero Manzoni Catalogue Raisoné, Battino & Palazzoli, p. 109

- ↑ Piero Manzoni Catalog Generale, vol 1, Celant pp. 286-287

- ↑ Hulten, P. Una magia più forte della morte. Bompiani. p. 66.

- ↑ Manzoni, Clemant, Electa 2007. p 61

- ↑ New Media Studies

External links

- The Piero Manzoni Archive

- Space Place