Docking (molecular)

| Docking glossary |

|---|

|

In the field of molecular modeling, docking is a method which predicts the preferred orientation of one molecule to a second when bound to each other to form a stable complex.[1] Knowledge of the preferred orientation in turn may be used to predict the strength of association or binding affinity between two molecules using, for example, scoring functions.

The associations between biologically relevant molecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, and lipids play a central role in signal transduction. Furthermore, the relative orientation of the two interacting partners may affect the type of signal produced (e.g., agonism vs antagonism). Therefore, docking is useful for predicting both the strength and type of signal produced.

Molecular docking is one of the most frequently used methods in structure-based drug design, due to its ability to predict the binding-conformation of small molecule ligands to the appropriate target binding site. Characterisation of the binding behaviour plays an important role in rational design of drugs as well as to elucidate fundamental biochemical processes.[2]

Definition of problem

One can think of molecular docking as a problem of “lock-and-key”, in which one wants to find the correct relative orientation of the “key” which will open up the “lock” (where on the surface of the lock is the key hole, which direction to turn the key after it is inserted, etc.). Here, the protein can be thought of as the “lock” and the ligand can be thought of as a “key”. Molecular docking may be defined as an optimization problem, which would describe the “best-fit” orientation of a ligand that binds to a particular protein of interest. However, since both the ligand and the protein are flexible, a “hand-in-glove” analogy is more appropriate than “lock-and-key”.[3] During the course of the docking process, the ligand and the protein adjust their conformation to achieve an overall "best-fit" and this kind of conformational adjustment resulting in the overall binding is referred to as "induced-fit".[4]

Molecular docking research focusses on computationally simulating the molecular recognition process. It aims to achieve an optimized conformation for both the protein and ligand and relative orientation between protein and ligand such that the free energy of the overall system is minimized.

Docking approaches

Two approaches are particularly popular within the molecular docking community. One approach uses a matching technique that describes the protein and the ligand as complementary surfaces.[5][6][7] The second approach simulates the actual docking process in which the ligand-protein pairwise interaction energies are calculated.[8] Both approaches have significant advantages as well as some limitations. These are outlined below.

Shape complementarity

Geometric matching/ shape complementarity methods describe the protein and ligand as a set of features that make them dockable.[9] These features may include molecular surface / complementary surface descriptors. In this case, the receptor’s molecular surface is described in terms of its solvent-accessible surface area and the ligand’s molecular surface is described in terms of its matching surface description. The complementarity between the two surfaces amounts to the shape matching description that may help finding the complementary pose of docking the target and the ligand molecules. Another approach is to describe the hydrophobic features of the protein using turns in the main-chain atoms. Yet another approach is to use a Fourier shape descriptor technique.[10][11][12] Whereas the shape complementarity based approaches are typically fast and robust, they cannot usually model the movements or dynamic changes in the ligand/ protein conformations accurately, although recent developments allow these methods to investigate ligand flexibility. Shape complementarity methods can quickly scan through several thousand ligands in a matter of seconds and actually figure out whether they can bind at the protein’s active site, and are usually scalable to even protein-protein interactions. They are also much more amenable to pharmacophore based approaches, since they use geometric descriptions of the ligands to find optimal binding.

Simulation

Simulating the docking process as such is much more complicated. In this approach, the protein and the ligand are separated by some physical distance, and the ligand finds its position into the protein’s active site after a certain number of “moves” in its conformational space. The moves incorporate rigid body transformations such as translations and rotations, as well as internal changes to the ligand’s structure including torsion angle rotations. Each of these moves in the conformation space of the ligand induces a total energetic cost of the system. Hence, the system's total energy is calculated after every move.

The obvious advantage of docking simulation is that ligand flexibility is easily incorporated, whereas shape complementarity techniques must use ingenious methods to incorporate flexibility in ligands. Also, it more accurately models reality, whereas shape complimentary techniques are more of an abstraction.

Clearly, simulation is computationally expensive, having to explore a large energy landscape. Grid-based techniques, optimization methods, and increased computer speed have made docking simulation more realistic.

Mechanics of docking

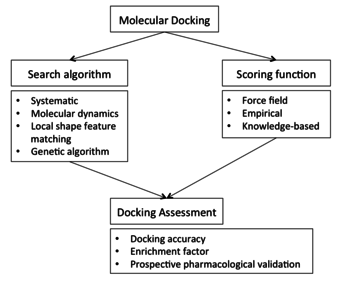

To perform a docking screen, the first requirement is a structure of the protein of interest. Usually the structure has been determined using a biophysical technique such as x-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy, but can also derive from homology modeling construction. This protein structure and a database of potential ligands serve as inputs to a docking program. The success of a docking program depends on two components: the search algorithm and the scoring function.

Search algorithm

The search space in theory consists of all possible orientations and conformations of the protein paired with the ligand. However, in practice with current computational resources, it is impossible to exhaustively explore the search space—this would involve enumerating all possible distortions of each molecule (molecules are dynamic and exist in an ensemble of conformational states) and all possible rotational and translational orientations of the ligand relative to the protein at a given level of granularity. Most docking programs in use account for the whole conformational space of the ligand (flexible ligand), and several attempt to model a flexible protein receptor. Each "snapshot" of the pair is referred to as a pose.

A variety of conformational search strategies have been applied to the ligand and to the receptor. These include:

- systematic or stochastic torsional searches about rotatable bonds

- molecular dynamics simulations

- genetic algorithms to "evolve" new low energy conformations and where the score of each pose acts as the fitness function used to select individuals for the next iteration.

Ligand flexibility

Conformations of the ligand may be generated in the absence of the receptor and subsequently docked[13] or conformations may be generated on-the-fly in the presence of the receptor binding cavity,[14] or with full rotational flexibility of every dihedral angle using fragment based docking.[15] Force field energy evaluation are most often used to select energetically reasonable conformations,[16] but knowledge-based methods have also been used.[17]

Receptor flexibility

Computational capacity has increased dramatically over the last decade making possible the use of more sophisticated and computationally intensive methods in computer-assisted drug design. However, dealing with receptor flexibility in docking methodologies is still a thorny issue. The main reason behind this difficulty is the large number of degrees of freedom that have to be considered in this kind of calculations. Neglecting it, however, leads to poor docking results in terms of binding pose prediction.[18]

Multiple static structures experimentally determined for the same protein in different conformations are often used to emulate receptor flexibility.[19] Alternatively rotamer libraries of amino acid side chains that surround the binding cavity may be searched to generate alternate but energetically reasonable protein conformations.[20][21]

Scoring function

Docking programs generate a large number of potential ligand poses, of which some can be immediately rejected due to clashes with the protein. The remainder are evaluated using some scoring function, which takes a pose as input and returns a number indicating the likelihood that the pose represents a favorable binding interaction and ranks one ligand relative to another.

Most scoring functions are physics-based molecular mechanics force fields that estimate the energy of the pose within the binding site. The various contributions to binding can be written as an additive equation:

The components consist of solvent effects, conformational changes in the protein and ligand, free energy due to protein-ligand interactions, internal rotations, association energy of ligand and receptor to form a single complex and free energy due to changes in vibrational modes.[22] A low (negative) energy indicates a stable system and thus a likely binding interaction.

An alternative approach is to derive a knowledge-based statistical potential for interactions from a large database of protein-ligand complexes, such as the Protein Data Bank, and evaluate the fit of the pose according to this inferred potential.

There are a large number of structures from X-ray crystallography for complexes between proteins and high affinity ligands, but comparatively fewer for low affinity ligands as the later complexes tend to be less stable and therefore more difficult to crystallize. Scoring functions trained with this data can dock high affinity ligands correctly, but they will also give plausible docked conformations for ligands that do not bind. This gives a large number of false positive hits, i.e., ligands predicted to bind to the protein that actually don't when placed together in a test tube.

One way to reduce the number of false positives is to recalculate the energy of the top scoring poses using (potentially) more accurate but computationally more intensive techniques such as Generalized Born or Poisson-Boltzmann methods.[8]

Docking assessment

The interdependence between sampling and scoring function affects the docking capability in predict plausible poses or binding affinities for novel compounds. Thus, an assessment of a docking protocol is generally required (when experimental data is available) to determine its predictive capability. Docking assessment can be performed using different strategies, such as:

- docking accuracy (DA) calculation;

- the correlation between a docking score and the experimental response or determination of the enrichment factor (EF);[23]

- the distance between an ion-binding moiety and the ion in the active site;

- the presence of induce-fit models.

Docking accuracy

Docking accuracy[24][25] represents one measure to quantify the fitness of a docking program by rationalizing the ability to predict the right pose of a ligand with respect to that experimentally observed.

Enrichment factor

Docking screens can be also evaluated by the enrichment of annotated ligands of known binders from among a large database of presumed non-binding, “decoy” molecules.[23] In this way, the success of a docking screen is evaluated by its capacity to enrich the small number of known active compounds in the top ranks of a screen from among a much greater number of decoy molecules in the database. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is widely used to evaluate its performance.

Prospective

Resulting hits from docking screens are subjected to pharmacological validation (e.g. IC50, affinity or potency measurements). Only prospective studies constitute conclusive proof of the suitability of a technique for a particular target.[26]

Benchmarking

The potential of docking programs to reproduce binding modes as determined by X-ray crystallography can be assed by a range of docking benchmark sets.

For small molecules, several benchmark data sets for docking and virtual screening exist e.g. Astex Diverse Set consisting of high quality protein−ligand X-ray crystal structures[27] or the Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) for evaluation of virtual screening performance.[23]

An evaluation of docking programs for their potential to reproduce peptide binding modes can be assessed by Lessons for Efficiency Assessment of Docking and Scoring (LEADS-PEP).[28]

Applications

A binding interaction between a small molecule ligand and an enzyme protein may result in activation or inhibition of the enzyme. If the protein is a receptor, ligand binding may result in agonism or antagonism. Docking is most commonly used in the field of drug design — most drugs are small organic molecules, and docking may be applied to:

- hit identification – docking combined with a scoring function can be used to quickly screen large databases of potential drugs in silico to identify molecules that are likely to bind to protein target of interest (see virtual screening).

- lead optimization – docking can be used to predict in where and in which relative orientation a ligand binds to a protein (also referred to as the binding mode or pose). This information may in turn be used to design more potent and selective analogs.

- Bioremediation – Protein ligand docking can also be used to predict pollutants that can be degraded by enzymes.[29]

List of protein-ligand docking software

The number of docking programs currently available is high and has been steadily increasing over the last decades. The following list presents an overview of the most common protein-ligand docking programs, listed alphabetically, with indication of the corresponding year of publication, involved organisation or institution, short description, availability of a webservice and the license. This table is comprehensive but not complete.

| Program | Year Published | Organisation | Description | Webservice | License |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Click Docking | 2011 | Mcule | Docking predicts the binding orientation and affinity of a ligand to a target | Available → | Basic free version |

| AADS | 2011 | Indian Institute of Technology | Automated active site detection, docking, and scoring(AADS) protocol for proteins with known structures based on Monte Carlo Method | Available → | Free to use Webservice |

| ADAM | 1994 | IMMD Inc. | Prediction of stable binding mode of flexible ligand molecule to target macromolecule | No | Commercial |

| AutoDock | 1990 | The Scripps Research Institute | Automated docking of ligand to macromolecule by Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and Empirical Free Energy Scoring Function | No | Freeware → |

| AutoDock Vina | 2010 | The Scripps Research Institute | New generation of AutoDock | No | Open source → |

| BetaDock | 2011 | Hanyang University | Based on Voronoi Diagram | No | Freeware → |

| Blaster | 2009 | University of California San Francisco | Combines ZINC databases with DOCK to find ligand for target protein | Available → | Freeware |

| BSP-SLIM | 2012 | University of Michigan | A new method for ligand-protein blind docking using low-resolution protein structures | Available → | Freeware |

| DARWIN | 2000 | The Wistar Institute | Prediction of the interaction between a protein and another biological molecule by genetic algorithm | No | Freeware |

| DIVALI | 1995 | University of California-San Francisco | Based on AMBER-type potential function and genetic algorithm | No | Freeware |

| DOCK | 1988 | University of California-San Francisco | Based on Geometric Matching Algorithm | No | Freeware for academic use → |

| DockingServer | 2009 | Virtua Drug Ltd | Integrates a number of computational chemistry software | Available → | Commercial |

| DockVision | 1992 | DockVision | Based on Monte Carlo, genetic algorithm, and database screening docking algorithms | No | Commercial → |

| EADock | 2007 | Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics | Based on evolutionary algorithms | Available → | Freeware → |

| eHiTS | 2006 | SymBioSys Inc | Exhausted search algorithm | No | Commercial → |

| EUDOC | 2001 | Mayo Clinic Cancer Center | Program for identification of drug interaction sites in macromolecules and drug leads from chemical databases | No | Academic |

| FDS | 2003 | University of Southampton | Flexible ligand and receptor docking with a continuum solvent model and soft-core energy function | No | Academic |

| FlexX | 2001 | BioSolveIT | Incremental build based docking program | No | Commercial → |

| FlexAID | 2015 | University of Sherbrooke | Target side-chain flexibility and soft scoring function, based on surface complementarity | No | Open source → |

| FlexPepDock | 2010 | The Hebrew University | Modeling of peptide-protein complexes, implemented within the Rosetta framework | Available → | Freeware |

| FLIPDock | 2007 | Scripps Research Institute | Genetic algorithm based docking program using FlexTree data structures to represent a protein-ligand complex | No | Free for academic use → |

| FLOG | 1994 | Merck Research Laboratories | Rigid body docking program using databases of pregenerated conformations | No | Academic |

| FRED | 2003 | OpenEye Scientific | Systematic, exhaustive, nonstochastic examination of all possible poses within the protein active site combined with scoring Function | No | Free for academic use → |

| FTDOCK | 1997 | Biomolecular Modelling Laboratory | Based on Katchalski-Katzir algorithm. It discretises the two molecules onto orthogonal grids and performs a global scan of translational and rotational space | No | Freeware → |

| GEMDOCK | 2004 | National Chiao Tung University | Generic Evolutionary Method for molecular docking | No | Freeware → |

| Glide | 2004 | Schrödinger | Exhaustive search based docking program | No | Commercial → |

| GOLD | 1995 | Collaboration between the University of Sheffield, GlaxoSmithKline plc and CCDC | Genetic algorithm based, flexible ligand, partial flexibility for protein | No | Commercial |

| GPCRautomodel | 2012 | INRA | Automates the homology modeling of mammalian olfactory receptors (ORs) based on the six three-dimensional (3D) structures of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) available so far and performs the docking of odorants on these models | Available → | Free for academic use |

| HADDOCK | 2003 | Centre Bijvoet Center for Biomolecular Research | Makes use of biochemical and/or biophysical interaction data such as chemical shift perturbation data resulting from NMR titration experiments, mutagenesis data or bioinformatic predictions. Developed for protein-protein docking, but can also be applied to protein-ligand docking. | Available → | Freeware → |

| Hammerhead | 1996 | Arris Pharmaceutical Corporation | Fast, fully automated docking of flexible ligands to protein binding sites | No | Academic |

| ICM-Dock | 1997 | MolSoft | Docking program based on pseudo-Brownian sampling and local minimization | No | Commercial → |

| idTarget | 2012 | National Taiwan University | Predicts possible binding targets of a small chemical molecule via a divide-and-conquer docking approach | Available → | Freeware |

| iScreen | 2011 | China Medical University | Based on a cloud-computing system for TCM intelligent screening system | Available → | Freeware |

| Lead finder | 2008 | MolTech | Program for molecular docking, virtual screening and quantitative evaluation of ligand binding and biological activity | No | Commercial → |

| LigandFit | 2003 | BioVia | CHARMm based docking program | No | Commercial |

| LigDockCSA | 2011 | Seoul National University | Protein-ligand docking using conformational space annealing | No | Academic |

| LIGIN | 1996 | Weizmann Institute of Science | Molecular docking using surface complementarity | No | Commercial |

| LPCCSU | 1999 | Weizmann Institute of Science | Based on a detailed analysis of interatomic contacts and interface complementarity | Available → | Freeware |

| MCDOCK | 1999 | Georgetown University Medical Center | Based on a non-conventional Monte Carlo simulation technique | No | Academic |

| MEDock | 2007 | SIGMBI | Maximum-Entropy based Docking web server is aimed at providing an efficient utility for prediction of ligand binding site | Available → | Freeware |

| MOE | 2005 | Chemical Computing Group | Supply a database of conformations or generate conformations on the fly. Choose between various scoring functions[30] and optionally constrain the generated poses to satisfy a pharmacophore query to bias the search towards known important interactions. Refine the poses using a forcefield based method with MM/GBVI[31] scoring or a fast grid based method. | No | Commercial |

| MolDock | 2006 | Molegro ApS | Based on a new heuristic search algorithm that combines differential evolution with a cavity prediction algorithm | No | Academic |

| MS-DOCK | 2008 | INSERM | Multi-stage docking/scoring protocol | No | Academic |

| ParDOCK | 2007 | Indian Institute of Technology | All-atom energy based Monte Carlo, rigid protein ligand docking | Available → | Freeware |

| PatchDock | 2002 | Tel Aviv University | The algorithm carries out rigid docking, with surface variability/flexibility implicitly addressed through liberal intermolecular penetration | Available → | Freeware |

| PLANTS | 2006 | University of Konstanz | Based on a class of stochastic optimization algorithms (ant colony optimization) | No | Free for academic use |

| PLATINUM | 2008 | Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (State University) | Analysis and visualization of hydrophobic/hydrophilic properties of biomolecules supplied as 3D-structures | Available → | Freeware |

| PRODOCK | 1999 | Cornell University | Based on Monte Carlo method plus energy minimization | No | Academic |

| PSI-DOCK | 2006 | Peking University | Pose-Sensitive Inclined (PSI)-DOCK | No | Academic |

| PSO@AUTODOCK | 2007 | University of Leipzig | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithms varCPSO and varCPSO-ls are suited for rapid docking of highly flexible ligands | No | Academic |

| PythDock | 2011 | Hanyang University | Heuristic docking program that uses Python programming language with a simple scoring function and a population based search engine; source codes available (Jaeyoon Chung; jychung@bu.edu) | Available | Academic |

| Q-Dock | 2008 | Georgia Institute of Technology | Low-resolution flexible ligand docking with pocket-specific threading restraints | No | Freeware |

| QXP | 1997 | Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation | Monte Carlo perturbation with energy minimization in Cartesian space | No | Academic |

| rDock | 2013 | University of York/ Open source project | HTVS of small molecules against proteins and nucleic acids | No | Open source → |

| SANDOCK | 1998 | University of Edinburgh | Guided matching algorithm | No | Academic |

| Score | 2004 | Alessandro Pedretti & Giulio Vistoli | The Score service allows to calculate some different docking scores of ligand-receptor complex | Available → | Freeware |

| SODOCK | 2007 | Feng Chia University (Taiwan) | Swarm optimization for highly flexible protein-ligand docking | No | Academic |

| SOFTDocking | 1991 | University of California, Berkeley | Matching of molecular surface cubes | No | Academic |

| Surflex-Dock | 2003 | Tripos | Based on an idealized active site ligand (a protomol) | No | Commercial → |

| SwissDock | 2011 | Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics | Webservice to predict interaction between a protein and a small molecule ligand | Available → | Free webservice for academic use |

| VoteDock | 2011 | University of Warsaw | Consensus docking method for prediction of protein-ligand interactions | No | Academic |

| YUCCA | 2005 | Virginia Tech | Rigid protein-small-molecule docking | No | Academic |

| MOLS 2.0 | 2016 | University of Madras | Software package for peptide modeling and protein-ligand docking | No | Open Source |

See also

- Drug design

- Katchalski-Katzir algorithm

- List of molecular graphics systems

- Macromolecular docking

- Molecular mechanics

- Protein structure

- Protein design

- Software for molecular mechanics modeling

- Molecular design software

- Docking@Home

- Ibercivis

- ZINC database

- Lead Finder

- Virtual screening

- Scoring functions for docking

References

- ↑ Lengauer T, Rarey M (Jun 1996). "Computational methods for biomolecular docking". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 6 (3): 402–6. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(96)80061-3. PMID 8804827.

- ↑ Kitchen DB, Decornez H, Furr JR, Bajorath J (Nov 2004). "Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 3 (11): 935–49. doi:10.1038/nrd1549. PMID 15520816.

- ↑ Jorgensen WL (Nov 1991). "Rusting of the lock and key model for protein-ligand binding". Science. 254 (5034): 954–5. doi:10.1126/science.1719636. PMID 1719636.

- ↑ Wei BQ, Weaver LH, Ferrari AM, Matthews BW, Shoichet BK (Apr 2004). "Testing a flexible-receptor docking algorithm in a model binding site". Journal of Molecular Biology. 337 (5): 1161–82. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.015. PMID 15046985.

- ↑ Goldman BB, Wipke WT (2000). "QSD quadratic shape descriptors. 2. Molecular docking using quadratic shape descriptors (QSDock)". Proteins. 38 (1): 79–94. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(20000101)38:1<79::AID-PROT9>3.0.CO;2-U. PMID 10651041.

- ↑ Meng EC, Shoichet BK, Kuntz ID (1992). "Automated docking with grid-based energy evaluation". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 13 (4): 505–524. doi:10.1002/jcc.540130412.

- ↑ Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ (1998). "Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 19 (14): 1639–1662. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19981115)19:14<1639::AID-JCC10>3.0.CO;2-B.

- 1 2 Feig M, Onufriev A, Lee MS, Im W, Case DA, Brooks CL (Jan 2004). "Performance comparison of generalized born and Poisson methods in the calculation of electrostatic solvation energies for protein structures". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 25 (2): 265–84. doi:10.1002/jcc.10378. PMID 14648625.

- ↑ Shoichet BK, Kuntz ID, Bodian DL (2004). "Molecular docking using shape descriptors". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 13 (3): 380–397. doi:10.1002/jcc.540130311.

- ↑ Cai W, Shao X, Maigret B (Jan 2002). "Protein-ligand recognition using spherical harmonic molecular surfaces: towards a fast and efficient filter for large virtual throughput screening". Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling. 20 (4): 313–28. doi:10.1016/S1093-3263(01)00134-6. PMID 11858640.

- ↑ Morris RJ, Najmanovich RJ, Kahraman A, Thornton JM (May 2005). "Real spherical harmonic expansion coefficients as 3D shape descriptors for protein binding pocket and ligand comparisons". Bioinformatics. 21 (10): 2347–55. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti337. PMID 15728116.

- ↑ Kahraman A, Morris RJ, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM (Apr 2007). "Shape variation in protein binding pockets and their ligands". Journal of Molecular Biology. 368 (1): 283–301. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.086. PMID 17337005.

- ↑ Kearsley SK, Underwood DJ, Sheridan RP, Miller MD (Oct 1994). "Flexibases: a way to enhance the use of molecular docking methods". Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 8 (5): 565–82. doi:10.1007/BF00123666. PMID 7876901.

- ↑ Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS (Mar 2004). "Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 47 (7): 1739–49. doi:10.1021/jm0306430. PMID 15027865.

- ↑ Zsoldos Z, Reid D, Simon A, Sadjad SB, Johnson AP (Jul 2007). "eHiTS: a new fast, exhaustive flexible ligand docking system". Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling. 26 (1): 198–212. doi:10.1016/j.jmgm.2006.06.002. PMID 16860582.

- ↑ Wang Q, Pang YP (2007). Romesberg F, ed. "Preference of small molecules for local minimum conformations when binding to proteins". PLOS ONE. 2 (9): e820. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000820. PMC 1959118

. PMID 17786192.

. PMID 17786192. - ↑ Klebe G, Mietzner T (Oct 1994). "A fast and efficient method to generate biologically relevant conformations". Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 8 (5): 583–606. doi:10.1007/BF00123667. PMID 7876902.

- ↑ Cerqueira NM, Bras NF, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ (Jan 2009). "MADAMM: a multistaged docking with an automated molecular modeling protocol". Proteins. 74 (1): 192–206. doi:10.1002/prot.22146. PMID 18618708.

- ↑ Totrov M, Abagyan R (Apr 2008). "Flexible ligand docking to multiple receptor conformations: a practical alternative". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 18 (2): 178–84. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2008.01.004. PMC 2396190

. PMID 18302984.

. PMID 18302984. - ↑ Hartmann C, Antes I, Lengauer T (Feb 2009). "Docking and scoring with alternative side-chain conformations". Proteins. 74 (3): 712–26. doi:10.1002/prot.22189. PMID 18704939.

- ↑ Taylor RD, Jewsbury PJ, Essex JW (Oct 2003). "FDS: flexible ligand and receptor docking with a continuum solvent model and soft-core energy function". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 24 (13): 1637–56. doi:10.1002/jcc.10295. PMID 12926007.

- ↑ Murcko MA (Dec 1995). "Computational Methods to Predict Binding Free Energy in Ligand-Receptor Complexes". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 38 (26): 4953–67. doi:10.1021/jm00026a001. PMID 8544170.

- 1 2 3 Huang N, Shoichet BK, Irwin JJ (Nov 2006). "Benchmarking sets for molecular docking". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 49 (23): 6789–801. doi:10.1021/jm0608356. PMC 3383317

. PMID 17154509.

. PMID 17154509. - ↑ Ballante F, Marshall GR (Jan 2016). "An Automated Strategy for Binding-Pose Selection and Docking Assessment in Structure-Based Drug Design". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00603. PMID 26682916.

- ↑ Bursulaya BD, Totrov M, Abagyan R, Brooks CL (Nov 2003). "Comparative study of several algorithms for flexible ligand docking". Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 17 (11): 755–63. doi:10.1023/B:JCAM.0000017496.76572.6f. PMID 15072435.

- ↑ Irwin JJ (2008-02-14). "Community benchmarks for virtual screening". Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 22 (3-4): 193–9. doi:10.1007/s10822-008-9189-4. PMID 18273555.

- ↑ Hartshorn MJ, Verdonk ML, Chessari G, Brewerton SC, Mooij WT, Mortenson PN, Murray CW (Feb 2007). "Diverse, high-quality test set for the validation of protein-ligand docking performance". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 50 (4): 726–41. doi:10.1021/jm061277y. PMID 17300160.

- ↑ Hauser AS, Windshügel B (Dec 2015). "A Benchmark Data Set for Assessment of Peptide Docking Performance". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00234. PMID 26651532.

- ↑ Suresh PS, Kumar A, Kumar R, Singh VP (Jan 2008). "An in silico [correction of insilico] approach to bioremediation: laccase as a case study". Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling. 26 (5): 845–9. doi:10.1016/j.jmgm.2007.05.005. PMID 17606396.

- ↑ Corbeil, C.R., Williams, C.I., Labute, P.; Variability in Docking Success Rates Due to Dataset Preparation; J. Comp.-Aided Mol. Des. 26 (2012) 775–786.

- ↑ Labute, P.; The Generalized Born / Volume Integral (GB/VI) Implicit Solvent Model: Estimation of the Free Energy of Hydration Using London Dispersion Instead of Atomic Surface Area; J. Comput. Chem. 29 (2008) 1963–1968.

External links

- Bikadi Z, Kovacs S, Demko L, Hazai E. "Molecular Docking Server - Ligand Protein Docking & Molecular Modeling". Virtua Drug Ltd. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

Internet service that calculates the site, geometry and energy of small molecules interacting with proteins

- Malinauskas T. "Step by step installation of MGLTools 1.5.2 (AutoDockTools, Python Molecular Viewer and Visual Programming Environment) on Ubuntu Linux 8.04". Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- Docking@GRID Project of Conformational Sampling and Docking on Grids : one aim is to deploy some intrinsic distributed docking algorithms on computational Grids, download Docking@GRID open-source Linux version

- Click2Drug.org - Directory of computational drug design tools.