Painted rocksnail

| Painted rocksnail | |

|---|---|

| |

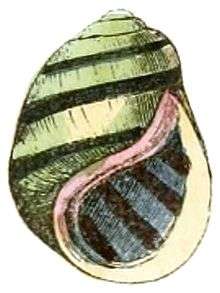

| Drawing of the shell of Leptoxis taeniata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| (unranked): | clade Caenogastropoda clade Sorbeoconcha |

| Superfamily: | Cerithioidea |

| Family: | Pleuroceridae |

| Genus: | Leptoxis |

| Species: | L. taeniata |

| Binomial name | |

| Leptoxis taeniata Conrad, 1834 | |

The painted rocksnail, scientific name Leptoxis taeniata, is a species of freshwater snail with a gill and an operculum, an aquatic gastropod mollusk in the family Pleuroceridae.

This species is endemic to the United States, specifically the state of Alabama. The snail has been listed as threatened on the United States Fish and Wildlife Service list of endangered species since October 28, 1998.[2]

Description

The painted rocksnail is a small to medium-sized pleurocerid snail with a shell that measures about 19 mm (0.8 in) in length, and is subglobose to oval in shape. The aperture is broadly ovate, and rounded anteriorly. The shell coloration varies from yellowish to olive-brown, usually with four dark bands. Some shells do not have these dark bands, and some have the bands broken into square or oblong patches (see Goodrich, 1922[3] for a detailed description).[4]

All of the rocksnails that historically inhabited the Mobile Basin had broadly rounded apertures, oval shaped shells, and variable coloration. Although the various species were distinguished by relative sizes, coloration patterns, and ornamentation, identification could be confusing. The painted rocksnail is the only known survivor of the 15 rocksnail species that historically occurred in the Coosa River drainage.[4]

Distribution

The painted rocksnail had the largest range of any rocksnail in the Mobile River Basin.[3] It was historically known from the Coosa River and tributaries from the northeastern corner of St. Clair County, Alabama, downstream into the mainstem of the Alabama River to Claiborne, Monroe County, Alabama, and the Cahaba River below the Fall Line in Perry and Dallas counties, Alabama.[3][5]

Surveys by Service biologists and others[6][7][8] in the Cahaba River, unimpounded portions of the Alabama River, and a number of free-flowing Coosa River tributaries have located only three localized Coosa River drainage populations.[4]

The painted rocksnail is currently known from the lower reaches of three Coosa River tributaries: Choccolocco Creek, Talladega County, Alabama; Buxahatchee Creek, Shelby County;[6] and Ohatchee Creek, Calhoun County, Alabama.[4][8]

Reasons for the decline

The Painted rocksnail has disappeared from more than 90 percent of its historic range. The curtailment of habitat and range for this (and few other snail species) species in the Mobile Basin's larger rivers (Coosa River, Alabama River and Cahaba River for Painted rocksnail) is primarily due to extensive construction of dams, and the subsequent inundation of the snail's shoal habitats by the impounded waters. This snail has disappeared from all portions of its historic habitats that have been impounded by dams.[4]

Dams change such areas by eliminating or reducing currents, and thus allowing sediments to accumulate on inundated channel habitats. Impounded waters also experience changes in water chemistry, which could affect survival or reproduction of riverine snails. For example, many reservoirs in the Basin currently experience eutrophic (enrichment of a water body with nutrients) conditions, and chronically low dissolved oxygen levels.[9][10] Such physical and chemical changes can affect feeding, respiration, and reproduction of these riffle and shoal snail species.[4]

Conservation

Tennessee Aquarium Research Institute (TNARI) has established captive populations of painted rocksnails. Releases of hatchery produced painted rocksnails were planned for 2005.[4] (update needed)

Ecology

Habitat

Painted rocksnails are gill-breathing snails which are found attached to cobble, gravel, or other hard substrates in the strong currents of riffles (a shallow area in a streambed that causes ripples in the water) and shoals.[4]

Life cycle

Adult rocksnails move around very little, and females probably glue their eggs to stones in the same habitat.[3] Longevity in the painted rocksnail is unknown but may be short: the lifespan in a Tennessee River rocksnail was reported as less than 2 years.[4][11]

References

This article incorporates public domain text (a public domain work of the United States Government) from the reference.[4]

- ↑ Bogan, A.E. 1996. Leptoxis taeniata. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 07 August 2007.

- ↑ Fish and Wildlife Service. (October 28) 1998. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Status for Three Aquatic Snails, and Threatened Status for Three Aquatic Snails in the Mobile River Basin of Alabama. Federal Register, Vol. 63, No. 208, Rules and Regulations, Accessed 26 January 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Goodrich C. 1922. The Anculosae of the Alabama River Drainage. Miscellaneous Publications, Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan (7):1-57.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2005. Recovery Plan for 6 Mobile River Basin Aquatic Snails. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Jackson, Mississippi. 46 pp. pages 9-10, page 15 and 17.

- ↑ Burch J.B. 1989. North American freshwater snails. Malacological Publications, Hamburg, Michigan. 365 pp.

- 1 2 Bogan A.E. & J.M. Pierson. 1993. Survey of the aquatic gastropods of the Coosa River Basin, Alabama: 1992. Alabama Natural Heritage Program. Contract Number 1923.

- ↑ Bogan A.E. & J.M. Pierson. 1993. Survey of the aquatic gastropods of the Cahaba River Basin, Alabama: 1992. Alabama Natural Heritage Program. Contract Number 1922.

- 1 2 M. Pierson, in litt., 1993

- ↑ Alabama Department of Environmental Management. 1994. Water quality report to Congress for calendar years 1992 and 1993. Montgomery, Alabama. 111 pp.

- ↑ Alabama Department of Environmental Management (ADEM). 1996. Water quality report to Congress for calendar years 1994 and 1995. Montgomery, Alabama. 144 pp.

- ↑ Heller J. 1990. Longevity in molluscs. Malacologia 31(2): 259-295.