Leonese dialect

| Leonese | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Spain, Portugal |

| Region | Provinces of Asturias, León (north and west), Zamora (north-west) in Spain,[1][2][3] and the towns of Rionor and Guadramil in northeastern Portugal;[4][5] Mirandese dialect in Portugal. |

Native speakers | 20,000–50,000 (2008)[6][7] |

| Official status | |

Official language in | As of 2010, has special status in the Spanish autonomous community of Castile and León |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog |

leon1250[8] |

| Linguasphere |

51-AAA-cc |

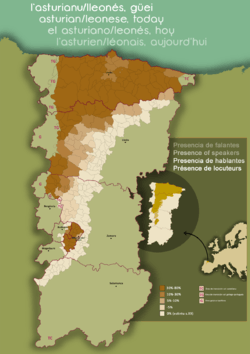

Leonese is a set of certain vernacular Romance dialects that are spoken in northern and western portions of the historical region of León in Spain (modern provinces of León, Zamora, and Salamanca), and in a few adjoining areas in Portugal. In this narrow sense, Leonese is different from the dialects grouped under Asturian,[9] though there is no clear division in purely linguistic terms. The current number of speakers of Leonese is estimated to be between about 20,000 and 50,000.[6][7][10] The westernmost fringes of the provinces of León and Zamora belong to the territory of the Galician language, though there is dialectal continuity between the linguistic areas.

The Leonese and Asturian dialects have long been recognized as constituting a single language, which is currently called Astur-Leonese (or Asturian-Leonese, etc.) by most scholars, but which used to be called "Leonese". For most of the 20th century, linguists (eminent among them Ramón Menéndez Pidal in his landmark 1906 study of the language)[11] spoke of a Leonese language or historical dialect descending from Latin, encompassing two groups: the Asturian dialects on the one hand, and on the other hand, certain dialects spoken in León and Zamora provinces in Spain, plus a related dialect in Trás-os-Montes, Portugal.[9][12][13]

Among the Leonese dialects are (from south to north) Senabrés, Cabreirés, and Pal.luezu; other Leonese dialects are indicated on the map of dialects below. Outside of Spain, there is also the Mirandese dialect spoken in Miranda do Douro, Portugal, which has experienced separate development and thus has its own standards. Nowadays, however, Mirandese is generally discussed separately from the remaining dialects of Leonese since it is not spoken in Spain.

Toponyms and other vocabulary related to Asturian-Leonese show that its linguistic traits had a larger geographical extension in the past, including eastern parts of the León and Zamora provinces, the Salamanca province, Cantabria, Extremadura, and even the Huelva province.

Unlike Asturian, the Leonese dialects of Spain do not enjoy official institutional promotion or regulation.

Name

Menéndez Pidal used the name Leonese for the whole linguistic area, including Asturias. In recent times, this designation has been replaced among scholars of Ibero-Romance with Asturian-Leonese, but Leonese is still often used to denote Asturian-Leonese by those who are not speakers of Asturian or Mirandese.[4][14] The Dictionary of the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language defines asturleonés (= Astur-Leonese) as a term of linguistic classification: [the] Romance dialect originating in Asturias and in the ancient Kingdom of León as a result of the local evolution of Latin, while it defines Leonese in geographical terms: the variety of Spanish spoken in Leonese territory. The reference to Leonese made in article 5.2 of the Statute of Autonomy of Castile and León has the former, broader denotation.[15]

Linguistic description

Phonology and writing

Phonology

In Leonese, any of five vowel phonemes, /a, e, i, o, u/, may occur in stressed position, and the two archiphonemes /I/, /U/ and the phoneme /a/ may occur in unstressed position.[16]

Writing

The Leonese dialects, unlike the Asturian dialects, do not have an official orthography. Some have proposed the establishment of a standard orthography for these dialects distinct from the official Asturian orthography, while others are content to use the latter.

Sample texts

| Locale | Province | Asturian-Leonese subdivision | Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carreño | Asturias | Central Asturian-Leonese | Tolos seres humanos nacen llibres y iguales en dignidá y drechos y, pola mor de la razón y la conciencia de so, han comportase fraternalmente los unos colos otros. |

| Somiedo | Asturias | Western Asturian-Leonese: Zone D | Tódolos seres humanos nacen ḷḷibres ya iguales en dignidá ya dreitos ya, dotaos cumo tán de razón ya conciencia, han portase fraternalmente los unos conos outros. |

| Pal.luezu | León | Western Asturian-Leonese: Zone D | Tódolos seres humanos nacen ḷḷibres ya iguales en dignidá ya dreitos ya, dotaos cumo tán de razón ya conciencia, han portase fraternalmente los unos conos outros. |

| Cabreira | León | Western Asturian-Leonese: Berciano-Cabreirés | Tódolos seres humanos ñacen llibres y iguales en dignidá y dreitos y, dotaos cumo están de razón y concéncia, han portase fraternalmente los unos pa coños outros. |

| Miranda | Trás-os-Montes (Portugal) | Western Asturian-Leonese: Mirandese | Todos ls seres houmanos nácen lhibres i eiguales an denidade i an dreitos. Custuituídos de rezon i de cuncéncia, dében portar-se uns culs outros an sprito de armandade. |

Historical changes

Some changes that occurred in the development of Leonese are given below:

- Initial /f/ from Latin is kept, like nearly all other western Romance varieties (the major maverick being Spanish, where /f/ > /h/ > Ø).

- The Latin initial consonant clusters /pl/, /kl/, /fl/ became /ʃ/.

- Proto-Romance medial clusters -ly- and -cl- became medieval /ʎ/, modern /j/. A parallel development occurred in Italian, where the -cl- became a voiced -gl- before shifting to /ʎ/.

- The cluster /-mb-/ is kept.

- Proto-Romance -mn- becomes /m/: lūm'nem > lume.

- The rising diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/ are preserved.

- Final -o becomes /u/.

- /l/ is palatalized word-initially (as in Catalan); sometimes /n/ as well.

- The medial cluster /sk/ becomes /ʃ/.

- Western Romance /ɛ/, /ɔ/ consistently diphthongize to /je/, /we/, even before palatals (as in Aragonese): terra > tierra "land", oc'lum > güeyu "eye".

Grammar

Leonese has two genders (masculine and feminine) and two numbers (singular and plural).

The main masculine noun and adjective endings are -u for the singular and -os for the plural. The typical feminine endings are -a for the singular and -as for the plural. Masculine and feminine nouns ending in -e in the singular take -es for the plural.

Adjectives

Adjectives agree with nouns in number and gender.

Comparative tables

| Gloss | Latin | Galician | Portuguese | Astur-Leonese | Castilian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diphthongization of 'o' and 'e' | |||||

| 'door' | porta(m) | porta | porta | puerta | puerta |

| 'eye' | oculu(m) | ollo | olho | güeyu/güechu | ojo |

| 'time' | tempu(m) | tempo | tempo | tiempu | tiempo |

| 'land' | terra(m) | terra | terra | tierra | tierra |

| Initial F- | |||||

| 'make' | facere | facer | fazer | facer | hacer |

| 'iron' | ferru(m) | ferro | ferro | fierru | hierro |

| Initial L- | |||||

| 'fireplace' | lare(m) | lar | lar | llar/ḷḷar | lar |

| 'wolf' | lupu(m) | lobo | lobo | llobu/ḷḷobu | lobo |

| Initial N- | |||||

| 'Christmas' | natal(is) / nativitate(m) | nadal | natal | ñavidá | navidad |

| pl-, cl-, fl- | |||||

| 'flat' | planu(m) | chan | chão | chanu/llanu | llano |

| 'key' | clave(m) | chave | chave | chave/llave | llave |

| 'flame' | flamma(m) | chama | chama | chama/llama | llama |

| Rising diphthongs | |||||

| 'thing' | causa(m) | cousa | cousa / coisa | cousa/cosa | cosa |

| 'blacksmith' | ferrariu(m) | ferreiro | ferreiro | ferreiru/-eru | herrero |

| -kt- and -lt- | |||||

| 'made' | factu(m) | feito | feito | feitu/fechu | hecho |

| 'night' | nocte(m) | noite | noite/n"ou"te | nueite/nueche | noche |

| 'much' | Multu(m) | moito | muito | mue'itu/muchu | mucho |

| 'listen' | auscultare | escoitar | escutar | escueitare/-chare | escuchar |

| m´n | |||||

| 'man' | hom(i)ne(m) | home | homem | home | hombre |

| 'hunger, famine' | faminem | fame | fome | fame | hambre |

| 'fire' | lum(i)ne(m) | lume | lume | llume/ḷḷume | lumbre |

| Intervocalic -l- | |||||

| 'ice' | gelu(m) | xeo | gelo | xelu | hielo |

| 'fern' | filictu(m) | fieito | feto | feleitu/-eichu | helecho |

| -ll- | |||||

| 'castle' | castellu(m) | castelo | castelo | castiellu/-ieḷḷu | castillo |

| Intervocalic -n- | |||||

| 'frog' | rana(m) | ra(n) | rã | rana | rana |

| -lj- | |||||

| 'woman' | muliere(m) | muller | mulher | muyer/mucher | mujer |

| c´l, t´l, g´l | |||||

| 'razor' | novacula(m) | navalla | navalha | ñavaya | navaja |

| 'old' | vetulu(m) | vello | velho | vieyu/viechu | viejo |

| 'tile' | tegula(m) | tella | telha | teya | teja |

Historical, social and cultural aspects

History of the language

The native languages of Leon and Zamora, as well as those from Asturias and the Terra de Miranda in Portugal are the result of the singular evolution of Latin introduced by the Roman conquerors in this area. Their colonization and organization led to the establishment of Conventus Astururum, with its capital in Asturica Augusta (what is now Astorga), the city that became the main centre of Romanization of the pre-existent tribes.[17]

The unitary conception of this area would remain until the Islamic invasion of the 7th century with the creation of an astur dukedom and a capital in Astorga, which together with other seven configured the Spanish territory both politically and administratively speaking. Later, about the 11th century, the area started to be defined as a Leonese territory that corresponded in general terms to the southern territory of the ancient convent. The great medieval reign was configured from this space spreading to all the centre and west of the Iberian Peninsula previously led from Cangas de Onís, Pravia, Oviedo and finally in the city of León. In this medieval reign of León the Romance languages Galician, Asturian-Leonese and Castilian were created and spread south as the reign consolidated its domain to the southern territories.

The first text known to have appeared in the Asturian-Leonese Romance language is the document Nodizia de Kesos, between 974 and 980 AD. The document contained an inventory of the cheese larder of a monastery. It was written in the margin on the back of a document that was written in Latin.[18]

Between the 12th and 13th centuries, Leonese reached its maximum territorial expansion. It was the administrative language of the Kingdom of León and a literary language. (Poema de Elena y María, El Libro de Alexandre…),[19][20] in the Leonese court, in justice (with the translation of the Liber Iudicum o Liber Iudiciorum Visigoth to leonés), in the administration and organization of the territory (as stated in the jurisdiction of Zamora, Salamanca, Leon, Oviedo, Avilés, etc.[21] which were written in Leonese from Latin). After the union of the reigns of Leon and Castile in the year 1230 Leonese reached a greater level of written and even institutional usage, although from the end of the 13th century Castilian started to replace Leonese in writing in a slow process not finally adopted until the 15th century.[22] The previous circumstances, together with the fact that the Leonese was not used in institutional and formal affairs, led Leonese to suffer a territorial withdrawal. From this moment Leonese in the ancient kingdom of Leon was reduced to an oral and rural language with very little literary development.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Leonese survived with relative firmness in the north and mid-west of Leon and in the west of Zamora. 1906 was the beginning of the scientific study of Leonese and a timid cultural movement of protest in the province of Leon. But starting in the 1950s and 60s, the number of Leonese speakers drastically decreased and the areas where it was spoken were also outstandingly reduced. This social and territorial withdrawal has not stopped yet, although the 80's were the beginning of a cultural movement of recovery and revalorization of Leonese linguistic patrimony, linguistic protests and promotion of the native language.[23]

Use and distribution

Geographical distribution

The geographical area of Leonese exceeds the administrative framework of the Autonomous Community of Castile and León such that the language known as Asturian or "bable" in the Autonomous Community in the Principality of Asturias is basically the same as the one known as Leonese in Castile and León. The fact that the geographical area is divided in two Spanish autonomous communities makes the recognition and promotion of this language in Asturias, although clearly insufficient, not to be regarded in Castile and León where the language in completely nonexistent in the official educative system, and lack measures of promotion by the autonomous administration.[24]

The Astur-Leonese linguistic domain covers nowadays approximately most of the principality of Asturias, the north and west of the province of Leon, the northeast of Zamora, both provinces in Castile and León, and the region of Miranda do Douro in the east of the Portuguese district of Bragança. However, the main objective of this article is the autonomous community of Castile and León.

Julio Borrego Nieto, in his work featured in Manual de dialectología española. El español de España (1996), points out that the area where Leonese is best maintained, defined as "area 1", "includes the west part of Leon and Zamora if we exclude those previously mentioned areas in which Galician features either dominate or mix with Leonese ones. Area 1 consists of the regions of Babia and Laciana, perhaps part of Luna and part of Los Argüellos, East Bierzo and the Cabrera; in Zamora, non-Galician Sanabria.

"Area 1" is where the traditional features of the Leonese people thrive (and thus affect a greater number of words) and have greater vitality (and thus are used by a greater number of inhabitants) to the extent that the dialect is perceived as a different code, capable of alternating with Spanish in a kind of "bilingual game". Borrego Nieto points out at last other geographical circle, which he calls "area 2", where Leonese has a fading presence and that: "[...] it is extended to the regions between the interior area and the Ribera del Órbigo (Maragatería, Cepeda, Omaña...). In Zamora, the region of La Carballeda – with the subregion La Requejada - and Aliste, with at least a part of its adjacent lands (Alba and Tábara). This area is characterized by a blur and progressive disappearance, greater as we move to the East, of the features still clearly seen in the previous area. The gradual and negative character of this characteristic explains how vague the limits are".

Use and status

Number of speakers

A "speaker of Leonese" is defined here as a person who knows and can speak a variety of Leonese.

There is no linguistic census that accurately provides the real number of speakers of the Leonese in the provinces of Leon and Zamora. The different estimates based on the current number of speakers of Leonese establish run from 5,000 to 50,000 people.

| Sociolinguistic study | Number of speakers |

|---|---|

| II Estudiu sociollingüísticu de Lleón (Identidá, conciencia d'usu y actitúes llingüístiques de la población lleonesa).[25] | 50,000 |

| Boletín de Facendera pola Llengua's newsletter].[26] | 25,000 |

| El asturiano-leonés: aspectos lingüísticos, sociolingüísticos y legislación.[27] | 20,000 to 25,000 |

| Linguas en contacto na bisbarra do Bierzo: castelán, astur-leonés e galego.[28] | 2,500 to 4,000* |

*Referred only to the counties of EL Bierzo, valles de Ribas de Sil, Fornela and La Cabrera.

Perceptions of speakers

In two recent sociolinguistic studies, made respectively in the north of Leon and in the entire province (Estudiu sociollingüísticu de Lleón. Uviéu, ALLA, 2006, and II Estudiu sociollingüísticu de Lleón. Uviéu, ALLA, 2008) and centred on the analysis of the prevalence of the Leonese, conscience of use and linguistic attitudes on the part of the traditional speakers of the Leonese, states:

"People from Leon appreciate their traditional language and are aware that this is a part of what we could refer to as 'Leonese culture.' In this sense, they completely reject the connection between its usage and linguistic incorrection. Although the traditional language is disappearing, fact most of the people in Leon are aware of, there is still a minimum number of users necessary to be able to initiate with guarantee a process of linguistic recuperation. To fight against this possibility of loss, most of the people in Leon are bound to the legal recognition of the traditional language, by collaborating with Asturias in linguistic politics, its presence at school and its institutional promotion."

About the needs and wishes expressed by the society in the province of León about Leonese, some data form the II Estudiu Sociollingüísticu de Lleón (2008) are revealing.

The maintenance of the traditional language is the main wish among people but with different options on how. Thus, almost 37% think that the language should be kept for nonofficial uses, and about 30% state that it should be used as Spanish. On the other hand, the wish that it disappears is expressed just by a 22% of the population.

Almost half of the population supports granting official status to the traditional language, through amending the Statute of Autonomy.

The convenience to establish forms of collaboration to develop proceedings of linguistic politics in a coordinated way between León and Asturias reaches a high percentage among population, so that about 7 out of 10 people are in favour of this idea whereas only a 20% of the people from Leon reject the option.

School study of the traditional language is demanded by more than 63% of the population. The resistance towards this possibility affect about 34% of the population

The positions in favour of the institutional promotion of the traditional language (especially by the town councils) get a percentage of more than 83% of the people's opinions. In fact, the questioning to the promotional labour hardly reaches the 13% of the people from Leon.

Political recognition

The Statute of Autonomy of Castile and León as amended 30 November 2007addresses the status of the Spanish, Leonese, and Galician languages. Section 5.2 provides:

"Leonese will be specifically protected by the institutions for its particular value within the linguistic patrimony of the Community. Its protection, usage and promotion will be regulated."

On 24 February 2010, the parliamentary group in the Courts of Castile and León of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party presented a Non-Legal Proposition in the Courts of Castile and León to:

- Recognise the value of Leonese within the linguistic patrimony of the Community and start a plan of measures aimed towards its specific protection in coordination with the rest of the public administrations.

- Fulfil the mandate established in article 5.2 of the Statute of Autonomy and, according to it, dictate Regulations about the protection, use and promotion of Leonese.

This proposition was approved unanimously by the Plenary session of the Parliament of Castile and León on May 26, 2010. Nevertheless, the position of the Government of Castile and León in relation with the promotion of the Leonese language one has not changed, and so no measure or plan has promised to be in order to give fulfillment to the article 5.2 of the Statute of Autonomy.

Vitality

The UNESCO, in its Atlas of Languages in Danger in the World,[29] includes Leonese among the endangered languages. Leonese is classified within the most at-risk category. This is qualified by attributing the following characteristics to Leonese:

- unofficial

- without legitimized significant use in the news media

- low levels of proficiency and use

- poor social prestige

- not used as a medium of primary education

- not used in official toponyms

Standardization

The Autonomous Community of Castile and León lacks a governmental agency to promote the minority languages in the community as well as a nongovernmental agency in an advisory capacity in matters pertaining to minority languages. The Academy of the Asturian Language has sponsored linguistic and sociolinguistic research, which encompasses non-Asturian dialects of Asturian-Leonese.

Two congresses about Leonese have been held from which the following measures have been proposed to move towards language standardization:

- Based on articles 5.2 and 5.3 of the Statute of Autonomy, raise the legal status of Leonese to equal that of Galician.

- Create an autonomous administrative organ under the Departament of Culture and Tourism responsible for protecting and promoting Leonese and Galician.

- Introduce the learning of Leonese in teaching of children and adults.

- Recover the native toponymy by implementing bilingual signage.

- Support the cultural and literary creation of Leonese and the Publications and editorials that use Leonese. Collaborate with the associations which base their work in the recovery of Leonese. Stimulate the presence of the Leonese in the social means of communication. Promote literary contests in Leonese.

- Promote the investigation about Leonese through the Universities of the Community and centres of study and investigation such as the Institute of Studies in Zamora, Cultural Institute in Leon, Institute of Studies of El Bierzo or the Institute of Studies of Astorga "Marcelo Macías".

- Coordinate the tasks of recovery in coordination and cooperation with linguistic institutions, centres of studies and administrations in the rest of the Asturialeonese linguistic area.

- Mandate that local governmental bodies assume responsibilities for the recovery of Leonese.

| Traditional (Leonese) |

Official (Castilian) |

|---|---|

| Los Argüechos / Argüeyos | Los Arguellos |

| Ponteo | Pontedo |

| Foyyeo | Folledo |

| Sayambre | Sajambre |

| Valdión | Valdeón |

| El Bierzu | El Bierzo |

| Cabreira | Cabrera |

| Maragatos | Maragatería |

| Oumaña | Omaña |

| Ḷḷaciana | Laciana |

| Furniella | Fornela |

| Senabria | Sanabria |

| La Carbayeda | La Carballeda |

Promotion

For approximately fifteen years, some cultural associations have offered Leonese language courses, sometimes with the support or collaboration of local administrations in the provinces of Leon and Zamora. The autonomous community of Castile and León has never collaborated in these courses, which, in most occasions, have taken place in precarious conditions, without continuity or by unqualified teachers and, very often, far from the area Leonese is spoken.

At the end of the 1990s, several associations unofficially promoted Leonese language courses. In 2001, the Universidad de León (University of León) created a course for teachers of Leonese, and local and provincial governments developed Leonese language courses for adults. Now Leonese can be studied in the most important villages of León, Zamora and Salamanca provinces in El Fueyu Courses, after the signing of an agreement between the Leonese Provincial Government and this organization. The Leonese Language Teachers and Monitors Association (Asociación de Profesores y Monitores de Llingua Llïonesa) was created in 2008 for the promotion of Leonese language activities.

Leonese language lessons started in 2008 with two schools and were taught in sixteen schools in León city until 2009, promoted by the Leonese local government's Department for Education. TheLeonese language course is for pupils in their 5th and 6th year of primary school (children 11 and 12 years old), where Leonese is taught, along with Leonese culture.

Leonese Language Day (Día de la Llingua Llïonesa) is a celebration for promoting the Leonese language and the advances in its field and was the result of a protocol signed between the Leonese provincial government and the Cultural Association for Leonese Language El Fueyu.[30]

Literature

Some examples of written literature:

- Benigno Suárez Ramos, El tío perruca, 1976. ISBN 978-84-400-1451-1.

- Cayetano Álvarez Bardón, Cuentos en dialecto leonés, 1981. ISBN 978-84-391-4102-0.

- Xuan Bello, Nel cuartu mariellu, 1982. ISBN 978-84-300-6521-9.

- Miguel Rojo, Telva ya los osos, 1994. ISBN 978-84-8053-040-8.

- Manuel García Menéndez, Corcuspin el Rozcayeiru, 1984. ISBN 978-84-600-3676-0.

- Manuel García Menéndez, Delina nel valle'l Faloupu, 1985. ISBN 978-84-600-4133-7.

- Eva González Fernández, Poesía completa : 1980-1991, 1991. ISBN 978-84-86936-58-7.

- VV.AA., Cuentos de Lleón - Antoloxía d'escritores lleoneses de güei, 1996. ISBN 84-87562-12-4.

- Roberto González-Quevedo, L.lume de l.luz, 2002. ISBN 978-84-8168-323-3.

- Roberto González-Quevedo, Pol sendeiru la nueite, 2002. ISBN 978-84-95640-37-6.

- Roberto González-Quevedo, Pan d'amore : antoloxía poética 1980-2003, 2004. ISBN 978-84-95640-95-6.

- Roberto González-Quevedo, El Sil que baxaba de la nieve, 2007. ISBN 978-84-96413-31-3.

- Emilce Núñez Álvarez, Atsegrías ya tristuras, 2005. ISBN 978-84-8177-093-3.

- Luis Cortés Vázquez, Leyendas, cuentos y romances de Sanabria, 2003. ISBN 978-84-95195-55-5.

- Ramón Menéndez Pidal, El dialecto leonés (Commemorative edition with stories and poems in Leonese), 2006. ISBN 978-84-933781-6-5.

- VV.AA., Cuentos populares leoneses (escritos por niños), 2006. ISBN 978-84-611-0795-7.

- Nicolás Bartolomé Pérez, Filandón: lliteratura popular llionesa, 2007. ISBN 978-84-933380-7-7.

- José Aragón y Escacena, Entre brumas, 1921. ISBN 978-84-8012-569-7.

- Francisco Javier Pozuelo Alegre, Poemas pa nun ser lleídos, 2008. ISBN 978-84-612-4484-3.

- Xosepe Vega Rodríguez, Epífora y outros rellatos, 2008. ISBN 978-84-612-5315-9.

- Xosepe Vega Rodríguez, Breve hestoria d'un gamusinu, 2008. ISBN 978-84-612-5316-6.

- VV.AA. (Antoine De Saint-Exupéry), El Prencipicu (Translation of The Little Prince), 2009. ISBN 978-84-96872-03-5.

- Ramón Rei Rodríguez, El ñegru amor, 2009. ISBN 978-84-613-1824-7.

- Juan Andrés Oria de Rueda Salguero, Llogas carbayesas, 2009. ISBN 978-84-613-1822-3.

See also

- Asturian language

- Mirandese language

- Spanish language

- Bercian dialect

- Asociación de Profesores y Monitores de Llingua Llïonesa

- Caitano Bardón

- Cuentos del Sil

- Eva González

- Leonese Language Day

References

- ↑ Herrero Ingelmo, J.L. "El Leonés en Salamanca cien años después"

- ↑ Llorente Maldonado, Antonio: "Las hablas vivas de Zamora y Salamanca en la actualidad"

- ↑ Borrego Nieto, Julio: "Leonés"

- 1 2 Menéndez Pidal, R. El Dialecto Leonés. Madrid. 1906

- ↑ Cruz, Luísa Segura da; Saramago, João and Vitorino, Gabriela: "Os dialectos leoneses em território português: coesão e diversidade". In "Variação Linguística no Espaço, no Tempo e na Sociedade". Associação Portuguesa de Linguística. Lisbon: Edições Colibri, p. 281-293. 1994.

- 1 2 González Riaño, Xosé Antón; García Arias, Xosé Lluis. II Estudiu Sociollingüísticu De Lleón: Identidá, conciencia d'usu y actitúes llingüístiques de la población lleonesa. Academia de la Llingua Asturiana, 2008. ISBN 978-84-8168-448-3

- 1 2 Sánchez Prieto, R. (2008): "La elaboración y aceptación de una norma lingüística en comunidades dialectalmente divididas: el caso del leonés y del frisio del norte". In: Sánchez Prieto, R./ Veith, D./ Martínez Areta, M. (ed.): Mikroglottika Yearbook 2008. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Leonese". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 Krüger, Fritz (2006): Estudio fonético-histórico de los dialectos españoles occidentales. Zamora: CSIC/Diputación de Zamora. p. 13

- ↑ García Gil (2008), page 12 : 20,000-25,000

- ↑ García Gil 2009, p. 10.

- ↑ Marcos, Ángel/Serra, Pedro (1999): Historia de la literatura portuguesa. Salamanca: Luso-Española. p. 9

- ↑ Menéndez Pidal, Ramón (1906): El dialecto leonés

- ↑ Morala Rodríguez, Jose Ramón. "El leonés en el siglo XXI (un romance milenario ante el reto de su normalización)", Instituto De La Lengua Castellano Y Leones, 2009. ISBN 978-84-936383-8-2

- ↑ Diario de León newspaper.

- ↑ Pardo, Abel: Linguistica contrastiva italiano-leonese. Mikroglottika.2008

- ↑ Santos, Juan. Comunidades indígenas y administración romana en el Noroeste hispánico, 1985. ISBN 978-84-7585-019-1.

- ↑ Orígenes de las lenguas romances en el Reino de León, siglos IX-XII, 2004, ISBN 978-84-87667-64-0

- ↑ Menéndez Pidal, Ramón. Elena y María. Disputa del clérigo y el caballero. Poesía leonesa inédita del siglo XIII, 1914. ISSN 0210-9174

- ↑ The Leonese features in the Madrid manuscript of the Libro de Alexandre

- ↑ Carrasco Cantos, Pilar. Estudio léxico-semántico de los fueros leoneses de Zamora, Salamanca, Ledesma y Alba de Tormes: concordancias lematizadas, 1997. ISBN 978-84-338-2315-1.

- ↑ Lomax, Derek William. La lengua oficial de Castilla, 1971. Actele celui de al XII-lea Congres International de Lingvistica si Filologie Romanica

- ↑ "Llionés en marcha", La Nueva España newspaper.

- ↑ Los apellidos del habla, La Voz de Asturias Newspaper.

- ↑ González Riaño, Xosé Antón and García Arias, Xosé Lluis. II Estudiu sociollingüísticu de Lleón (Identidá, conciencia d'usu y actitúes llingüístiques de la población lleonesa), 2008. ISBN 978-84-8168-448-3

- ↑ Facendera pola Llengua's newsletter

- ↑ García Gil, Hector. El asturiano-leonés: aspectos lingüísticos, sociolingüísticos y legislación, 2010. ISSN 2013-102X

- ↑ Bautista, Alberto.Linguas en contacto na bisbarra do Bierzo, 2006. ISSN 1616-413X.

- ↑ Atlas of Languages in Danger in the World

- ↑ Official new of the signement of the Protocol between the Leonese Provincial Government and Leonese Language Association for developing the Leonese Language Day

Sources

- García Gil, Hector. 2008. Asturian-Leonese: linguistic, sociolinguistic, and legal aspects. Mercator legislation. Working Paper 25. Barcelona: CIEMEN.

- González Riaño, Xosé Antón; García Arias, Xosé Lluis: "II Estudiu Sociollingüísticu De Lleón: Identidá, conciencia d'usu y actitúes llingüístiques de la población lleonesa". Academia de la Llingua Asturiana, 2008. ISBN 978-84-8168-448-3.

- Linguasphere Register. 1999/2000 Edition. pp. 392. 1999.

- López-Morales, H.: "Elementos leoneses en la lengua del teatro pastoril de los siglos XV y XVI". Actas del II Congreso Internacional de Hispanistas. Instituto Español de la Universidad de Nimega. Holanda. 1967.

- Menéndez Pidal, R.: "El dialecto Leonés". Revista de Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos, 14. 1906.

- Pardo, Abel. "El Llïonés y las TICs". Mikroglottika Yearbook 2008. Págs 109-122. Peter Lang. Frankfurt am Main. 2008.

- Staaff, Erik. : "Étude sur l'ancien dialecte léonais d'après les chartes du XIIIe siècle", Uppsala. 1907.

Further reading

- Galmés de Fuentes, Álvaro; Catalán, Diego (1960). Trabajos sobre el dominio románico leonés. Editorial Gredos. ISBN 978-84-249-3436-1.

- Gessner, Emil. «Das Altleonesische: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis des Altspanischen».

- Hanssen, Friedrich Ludwig Christian (1896). Estudios sobre la conjugación Leonesa. Impr. Cervantes.

- Hanssen, Friedrich Ludwig Christian (1910). «Los infinitivos leoneses del Poema de Alexandre». Bulletin Hispanique (12).

- Krüger, Fritz. El dialecto de San Ciprián de Sanabria. Anejo IV de la RFE. Madrid.

- Morala Rodríguez, Jose Ramón; González-Quevedo, Roberto; Herreras, José Carlos; Borrego, Julio; Egido, María Cristina (2009). El Leonés en el Siglo XXI (Un Romance Milenario ante el Reto de su Normalización). Instituto De La Lengua Castellano Y Leones. ISBN 978-84-936383-8-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leonese language. |

| Look up Leonese language in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Leonese language |

| Asturian edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Leonese Council Official Website with information in Leonese

- Leonese Language Association

- Top Level Domain for Leonese

- Asociación de Profesores y Monitores de Llingua Llïonesa

- Llionpedia, an independent encyclopedia in Leonese