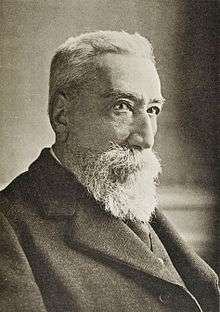

Anatole France

| Anatole France | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

François-Anatole Thibault 16 April 1844 Paris, Kingdom of France |

| Died |

12 October 1924 (aged 80) Tours, French Third Republic |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | French |

| Notable awards |

Nobel Prize in Literature 1921 |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

Anatole France (French: [anatɔl fʁɑ̃s]; born François-Anatole Thibault, [frɑ̃swa anatɔl tibo]; 16 April 1844 – 12 October 1924) was a French poet, journalist, and novelist. He was a successful novelist, with several best-sellers. Ironic and skeptical, he was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters. He was a member of the Académie française, and won the 1921 Nobel Prize in Literature "in recognition of his brilliant literary achievements, characterized as they are by a nobility of style, a profound human sympathy, grace, and a true Gallic temperament". Anatole France was also documented to have a brain volume just two-thirds the normal size.[1]

France is also widely believed to be the model for narrator Marcel's literary idol Bergotte in Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time.[2]

Early years

The son of a bookseller, France spent most of his life around books. France was a bibliophile.[3] His father's bookstore, called the Librairie France, specialized in books and papers on the French Revolution and was frequented by many notable writers and scholars of the day. Anatole France studied at the Collège Stanislas, a private Catholic school, and after graduation he helped his father by working in his bookstore. After several years he secured the position of cataloguer at Bacheline-Deflorenne and at Lemerre. In 1876 he was appointed librarian for the French Senate.

Literary career

Anatole France began his literary career as a poet and a journalist. In 1869, Le Parnasse Contemporain published one of his poems, La Part de Madeleine. In 1875, he sat on the committee which was in charge of the third Parnasse Contemporain compilation. As a journalist, from 1867, he wrote many articles and notices. He became famous with the novel Le Crime de Sylvestre Bonnard (1881). Its protagonist, skeptical old scholar Sylvester Bonnard, embodied France's own personality. The novel was praised for its elegant prose and won him a prize from the Académie française.

In La Rotisserie de la Reine Pedauque (1893) Anatole France ridiculed belief in the occult; and in Les Opinions de Jérôme Coignard (1893), France captured the atmosphere of the fin de siècle. France was elected to the Académie française in 1896.

France took an important part in the Dreyfus affair. He signed Émile Zola's manifesto supporting Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer who had been falsely convicted of espionage. France wrote about the affair in his 1901 novel Monsieur Bergeret.

France's later works include L'Île des Pingouins (1908) which satirizes human nature by depicting the transformation of penguins into humans – after the animals have been baptized by mistake by the nearsighted Abbot Mael. It is a satirical history of France, starting in Medieval times, going on to the writer's own time with special attention to the Dreyfus Affair and concluding with a dystopian future. Les dieux ont soif (1912) is a novel, set in Paris during the French Revolution, about a true-believing follower of Robespierre and his contribution to the bloody events of the Reign of Terror of 1793–94. It is a wake-up call against political and ideological fanaticism and explores various other philosophical approaches to the events of the time. La Revolte des Anges (1914) is often considered France's most profound novel. Loosley based on the Christian myth of the War in Heaven, it tells the story of Arcade, the guardian angel of Maurice d'Esparvieu. Arcade falls in love, joins the revolutionary movement of angels, and towards the end realizes that the overthrow of God is meaningless unless "in ourselves and in ourselves alone we attack and destroy Ialdabaoth."

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1921. He died in 1924 and is buried in the Neuilly-sur-Seine community cemetery near Paris.

On 31 May 1922, France's entire works were put on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Prohibited Books Index) of the Roman Catholic Church.[4] He regarded this as a "distinction".[5] This Index was abolished in 1966.

Private life

In 1877, Anatole France married Valérie Guérin de Sauville, a granddaughter of Jean-Urbain Guérin a miniaturist who painted Louis XVI,[6] with whom he had a daughter, Suzanne, in 1881 (dec. 1918). France's relations with women were always turbulent, and in 1888 he began a relationship with Madame Arman de Caillavet, who conducted a celebrated literary salon of the Third Republic; the affair lasted until shortly before her death in 1910.[6] After his divorce in 1893, he had many liaisons, notably with Mme Gagey, who committed suicide in 1911. France married again in 1920, Emma Laprévotte.[7]

Politically, Anatole France was a socialist and an outspoken supporter of the 1917 Russian Revolution. In 1920, France gave his support to the newly founded French Communist Party.[8]

Reputation

After his death in 1924 France was the object of written attacks, including a particularly venomous one from the Nazi collaborator, Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, and detractors decided he was a vulgar and derivative writer. An admirer, the English writer George Orwell, defended him however and declared that he remained very readable, and that "it is unquestionable that he was attacked partly from political motive."[11]

Works

Poetry

- Les Légions de Varus, poem published in 1867 in the Gazette rimée.

- Poèmes dorés (1873)

- Les Noces corinthiennes (The Bride of Corinth) (1876)

Prose fiction

- Jocaste et le chat maigre (Jocasta and the Famished Cat) (1879)

- Le Crime de Sylvestre Bonnard (The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard) (1881)

- Les Désirs de Jean Servien (The Aspirations of Jean Servien) (1882)

- Abeille (Honey-Bee) (1883)

- Balthasar (1889)

- Thaïs (1890)

- L’Étui de nacre (Mother of Pearl) (1892)

- La Rôtisserie de la reine Pédauque (At the Sign of the Reine Pédauque) (1892)

- Les Opinions de Jérôme Coignard (The Opinions of Jerome Coignard) (1893)

- Le Lys rouge (The Red Lily) (1894)

- Le Puits de Sainte Claire (The Well of Saint Clare) (1895)

- L’Histoire contemporaine (A Chronicle of Our Own Times)

- 1: L’Orme du mail (The Elm-Tree on the Mall)(1897)

- 2: Le Mannequin d'osier (The Wicker-Work Woman) (1897)

- 3: L’Anneau d'améthyste (The Amethyst Ring) (1899)

- 4: Monsieur Bergeret à Paris (Monsieur Bergeret in Paris) (1901)

- Clio (1900)

- Histoire comique (A Mummer's Tale) (1903)

- Sur la pierre blanche (The White Stone) (1905)

- L'Affaire Crainquebille (1901)

- L’Île des Pingouins (Penguin Island) (1908)

- Les Contes de Jacques Tournebroche (The Merrie Tales of Jacques Tournebroche) (1908)

- Les Sept Femmes de Barbe bleue et autres contes merveilleux (The Seven Wives of Bluebeard and Other Marvellous Tales) (1909)

- Les dieux ont soif (The Gods Are Athirst) (1912)

- La Révolte des anges (The Revolt of the Angels) (1914)

Memoirs

- Le Livre de mon ami (My Friend's Book) (1885)

- Pierre Nozière (1899)

- Le Petit Pierre (Little Pierre) (1918)

- La Vie en fleur (The Bloom of Life) (1922)

Plays

- Au petit bonheur (1898)

- Crainquebille (1903)

- La Comédie de celui qui épousa une femme muette (The Man Who Married A Dumb Wife) (1908)

- Le Mannequin d'osier (The Wicker Woman) (1928)

Historical biography

- Vie de Jeanne d'Arc (The Life of Joan of Arc) (1908)

Literary criticism

- Alfred de Vigny (1869)

- Le Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte (1888)

- Le Génie Latin (The Latin Genius) (1909)

Social criticism

- Le Jardin d’Épicure (The Garden of Epicurus) (1895)

- Opinions sociales (1902)

- Le Parti noir (1904)

- Vers les temps meilleurs (1906)

- Sur la voie glorieuse (1915)

- Trente ans de vie sociale, in four volumes, (1949, 1953, 1964, 1973)

References

- ↑ Keith, A (1927). "The Brain of Anatole France". British Medical Journal. 2 (3491): 1048–1049. PMC 2525321

.

. - ↑ "Marcel Proust: A Life, by Edmund White".

- ↑ "Anatole France". benonsensical. 24 July 2010.

- ↑ Halsall, Paul (May 1998). "Modern History Sourcebook: Index librorum prohibitorum, 1557–1966 (Index of Prohibited Books)". Internet History Sourcebooks Project (Fordham University).

- ↑ Current Opinion, September 1922, p. 295.

- 1 2 Édouard Leduc (2004). Anatole France avant l'oubli. Éditions Publibook. pp. 219, 222–. ISBN 978-2-7483-0397-1. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Lahy-Hollebecque, M. (1924). Anatole France et la femme. Baudinière, 1924, 252 p.

- ↑ "Anatole France". The Free Dictionary.

- ↑ http://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/anatole-france-694.php

- ↑ https://mereinkling.net/2014/08/11/introducing-anatole-france/

- ↑ Harrison, Bernard (2014-12-29). What Is Fiction For?: Literary Humanism Restored. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253014122.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anatole France |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anatole France. |

| Library resources about Anatole France |

| By Anatole France |

|---|

- Works by Anatole France at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Anatole France at Internet Archive

- Works by Anatole France at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Anatole France at Open Library

- Anatole France: A Brief Introduction

- Anatole France, Nobel Prize Winner by Herbert S. Gorman, The New York Times, 20 November 1921

- Correspondence with architect Jean-Paul Oury at Syracuse University

- Université McGill: le roman selon les romanciers

- (French) Anatole France, his work in audio version

- Dreyfus Rehabilitated

- Anatole France at Find a Grave