Lacquer

Lacquer is a clear or coloured wood finish that dries by solvent evaporation or a curing process that produces a hard, durable finish. This finish can be of any sheen level from ultra matte to high gloss, and it can be further polished as required. It is also used for "lacquer paint", which is a paint that typically dries better on a hard and smooth surface.

The term lacquer originates from the Sanskrit word lākshā (लाक्षा) representing the number 100,000, which was used for both the Lac insect (because of their enormous number) and the scarlet resinous secretion it produces that was used as wood finish in ancient India and neighbouring areas.[1] In terms of modern products for coating finishes, lac-based finishes are likely to be referred to as shellac, while lacquer often refers to other polymers dissolved in volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as nitrocellulose, and later acrylic compounds dissolved in lacquer thinner, a mixture of several solvents typically containing butyl acetate and xylene or toluene. Lacquer is more durable than shellac.

In the decorative arts, lacquer or lacquerware refers to a variety of techniques used to decorate wood, metal or other surfaces, especially carving into deep coatings of many layers of lacquer.

Etymology

The archaic French word lacre "a kind of sealing wax", from Portuguese lacre, unexplained variant of lacca "resinous substance", from Arabic lakk,from Odisha "Jau" from Telugu లక్క Persian lak, the verb lac meaning "to cover or coat with laqueur".[2] The root of the word is the Sanskrit word lākshā' (लाक्षा), which was used for both the Lac insect (because of their enormous number) and the scarlet resinous secretion it produces that was used as wood finish in ancient India and neighbouring areas.[1][3] Lac resin was once imported in sizeable quantity into Europe from India along with Eastern woods.[4][5]

Sheen measurement

Lacquer sheen is a measurement of the shine for a given lacquer.[6] Different manufacturers have their own names and standards for their sheen.[6] The most common names from least shiny to most shiny are: flat, matte, egg shell, satin, semi-gloss, and gloss (high).

Urushiol-based lacquers

Urushiol-based lacquers differ from most others, being slow-drying, and set by oxidation and polymerization, rather than by evaporation alone. In order for it to set properly it requires a humid and warm environment. The phenols oxidize and polymerize under the action of an enzyme laccase, yielding a substrate that, upon proper evaporation of its water content, is hard. These lacquers produce very hard, durable finishes that are both beautiful and very resistant to damage by water, acid, alkali or abrasion. The active ingredient of the resin is urushiol, a mixture of various phenols suspended in water, plus a few proteins. The resin is derived from a tree indigenous to China, species Toxicodendron vernicifluum, commonly known as the Lacquer Tree.[7] The fresh resin from the T. vernicifluum trees causes urushiol-induced contact dermatitis and great care is required in its use. The Chinese treated the allergic reaction with crushed shellfish, which supposedly prevents lacquer from drying properly.[8] Lacquer skills became very highly developed in Asia, and many highly decorated pieces were produced.

During the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BC), the sophisticated techniques used in the lacquer process were first developed and it became a highly artistic craft,[9] although various prehistoric lacquerwares have been unearthed in China dating back to the Neolithic period and objects with lacquer coating in Japan from the late Jōmon period.[9] The earliest extant lacquer object, a red wooden bowl,[10] was unearthed at a Hemudu culture (5000-4500 BC) site in China.[11] By the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), many centres of lacquer production became firmly established.[9] The knowledge of the Chinese methods of the lacquer process spread from China during the Han, Tang and Song dynasties, eventually it was introduced to Korea, Japan, Southeast and South Asia.[12]

There are two types of lacquer in India: one obtained from the T. vernicifluum tree and the other from an insect. In India the insect lac was once used from which a red dye was first extracted, later what was left of the insect was a grease that was used for lacquering objects. Trade of lacquer objects travelled through various routes to the Middle East. Known applications of lacquer in China included coffins, music instruments, furniture, and various household items.[9] Lacquer mixed with powdered cinnabar is used to produce the traditional red lacquerware from China.

The trees must be at least ten years old before cutting to bleed the resin. It sets by a process called "aqua-polymerization", absorbing oxygen to set; placing in a humid environment allows it to absorb more oxygen from the evaporation of the water.

Lacquer-yielding trees in Thailand, Vietnam, Burma and Taiwan, called Thitsi, are slightly different; they do not contain urushiol, but similar substances called "laccol" or "thitsiol". The end result is similar but softer than the Chinese or Japanese lacquer. Unlike Japanese and Chinese Toxicodendron verniciflua resin, Burmese lacquer does not cause allergic reactions; it sets slower, and is painted by craftsmen's hands without using brushes.

Raw lacquer can be "coloured" by the addition of small amounts of iron oxides, giving red or black depending on the oxide. There is some evidence that its use is even older than 8,000 years from archaeological digs in China. Later, pigments were added to make colours. It is used not only as a finish, but mixed with ground fired and unfired clays applied to a mould with layers of hemp cloth, it can produce objects without need for another core like wood. The process is called "kanshitsu" in Japan. Advanced decorative techniques using additional materials such as gold and silver powders and flakes ("makie") were refined to very high standards in Japan also after having been introduced from China. In the lacquering of the Chinese musical instrument, the guqin, the lacquer is mixed with deer horn powder (or ceramic powder) to give it more strength so it can stand up to the fingering.

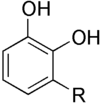

There are more than four forms of urushiol which is written as thus:

R = (CH2)14CH3 or

R = (CH2)14CH3 or

R = (CH2)7CH=CH(CH2)5CH3 or

R = (CH2)7CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)2CH3 or

R = (CH2)7CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH=CHCH3 or

R = (CH2)7CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CH2 and others.

Types of lacquer

Types of lacquer vary from place to place but they can be divided into unprocessed and processed categories.

The basic unprocessed lacquer is called raw lacquer (生漆: ki-urushi in Japanese, shengqi in Chinese). This is directly from the tree itself with some impurities filtered out. Raw lacquer has a water content of around 25% and appears in a light brown colour. This comes in a standard grade made from Chinese lacquer, which is generally used for ground layers by mixing with a powder, and a high quality grade made from Japanese lacquer called kijomi-urushi (生正味漆) which is used for the last finishing layers.

The processed form (in which the lacquer is stirred continuously until much of the water content has evaporated) is called guangqi (光漆) in Chinese but comes under many different Japanese names depending on the variation, for example, kijiro-urushi (木地呂漆) is standard transparent lacquer sometimes used with pigments and roiro-urushi (黒呂色漆) is the same but pre-mixed with iron hydroxide to produce a black coloured lacquer. Nashiji-urushi (梨子地漆) is the transparent lacquer but mixed with gamboge to create an even clearer lacquer and is especially used for the sprinkled-gold technique. These lacquers are generally used for the middle layers. Japanese lacquers of this type are generally used for the top layers and are prefixed by the word jo- (上) which means 'top (layer)'.

Processed lacquers can have oil added to them to make them glossy, for example, shuai-urushi (朱合漆) is mixed with linseed oil. Other specialist lacquers include ikkake-urushi (釦漆) which is thick and used mainly for applying gold or silver leaf.

Nitrocellulose lacquers

Slow-drying solvent-based lacquers that contain nitrocellulose, a resin obtained from the nitration of cotton and other cellulosic materials, were developed in the early 1920s, and extensively used in the automobile industry for 30 years. Prior to their introduction, mass-produced automotive finishes were limited in colour, with Japan Black being the fastest drying and thus most popular. General Motors Oakland automobile brand automobile was the first (1923) to introduce one of the new fast drying nitrocelluous lacquers, a bright blue, produced by DuPont under their Duco tradename.

These lacquers are also used on wooden products, furniture primarily, and on musical instruments and other objects. Nitrocellulose lacquers are also used to make firework fuses waterproof. The nitrocellulose and other resins and plasticizers are dissolved in the solvent, and each coat of lacquer dissolves some of the previous coat. These lacquers were a huge improvement over earlier automobile and furniture finishes, both in ease of application and in colour retention. The preferred method of applying quick-drying lacquers is by spraying, and the development of nitrocellulose lacquers led to the first extensive use of spray guns. Nitrocellulose lacquers produce a hard yet flexible, durable finish that can be polished to a high sheen. Drawbacks of these lacquers include the hazardous nature of the solvent, which is flammable and toxic, and the hazards of nitrocellulose in the manufacturing process. Lacquer grade of soluble nitrocellulose is closely related to the more highly nitrated form which is used to make explosives. They become relatively non-toxic after approximately a month since at this point, the lacquer has evaporated most of the solvents used in its production.

Acrylic lacquers

Lacquers using acrylic resin, a synthetic polymer, were developed in the 1950s. Acrylic resin is colourless, transparent thermoplastic, obtained by the polymerization of derivatives of acrylic acid. Acrylic is also used in enamel paints, which have the advantage of not needing to be buffed to obtain a shine. Enamels, however, are slow drying. The advantage of acrylic lacquer is its exceptionally fast drying time. The use of lacquers in automobile finishes was discontinued when tougher, more durable, weather- and chemical-resistant two-component polyurethane coatings were developed. The system usually consists of a primer, colour coat and clear topcoat, commonly known as clear coat finishes.

Water-based lacquers

Due to health risks and environmental considerations involved in the use of solvent-based lacquers, much work has gone into the development of water-based lacquers. Such lacquers are considerably less toxic and more environmentally friendly, and in many cases, produce acceptable results. While the fumes of water based lacquer are considerably less hazardous, and it does not have the combustibility issues of solvent based lacquers,the product still dries fairly quickly and even though the odor is weaker, the dust of dried and airborne lacquer can still get into the lungs;thus, proper protective wear still needs to be worn. More and more water-based colored lacquers are replacing solvent-based clear and colored lacquers in under hood and interior applications in the automobile and other similar industrial applications. Water based lacquers are used extensively in wood furniture finishing as well. One drawback of the water based lacquer is that it has a tendency to be highly reactive to other fresh finishes such as quick dry primer (excluding waterborne lacquer primers), caulking and even some paints that have a paint /primer aspect. Tannin bleed-through can also be an issue,depending on the brand of lacquer used. Once it happens, this is no easy fix as the lacquer is so reactive to other products. It is best when planning to spray a white based lacquer over raw wood to source and find a primer that will seal in the tannin. Some people will just use a clear to seal, which is fine but several light and fast drying coats must be applied to ensure a good seal. It is then recommended to wait until the next day to start spraying the color that way the clear has time to harden up and keep the white from pulling the tannin right through the clear. Also, depending on the state / province you are in,and how familiar your supplier is with wbl,it can be difficult to get any answers from your reps as many are unfamiliar with the potential reaction problems and how to fix them if they arise. Water based lacquer used for wood finishing is also not rated for exterior wear, unless otherwise specified.

Japanning

Just as china is a common name for porcelain, japanning is an old name to describe the European technique to imitate Asian lacquerware.[13] As Asian lacquer work became popular in England, France, the Netherlands, and Spain in the 17th century the Europeans developed imitations that were effectively a different technique of lacquering. The European technique, which is used on furniture and other objects, uses finishes that have a resin base similar to shellac. The technique, which became known as japanning, involves applying several coats of varnish which are each heat-dried and polished. In the 18th century, this type of lacquering gained a large popular following. Although traditionally a pottery and wood coating, japanning was the popular (mostly black) coating of the accelerating metalware industry. By the twentieth century, the term was freely applied to coatings based on various varnishes and lacquers besides the traditional shellac.

See also

References

- 1 2 Franco Brunello (1973), The art of dyeing in the history of mankind, AATCC, 1973,

... The word lacquer derives, in fact, from the Sanskrit 'Laksha' and has the same meaning as the Hindi word 'Lakh' which signifies one-hundred thousand ... enormous number of those parasitical insects which infest the plants Acacia catecu, Ficus and Butea frondosa ... great quantity of reddish colored resinous substance ... used in ancient times in India and other parts of Asia ...

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=lacquer

- ↑ Ulrich Meier-Westhues (November 2007), Polyurethanes: coatings, adhesives and sealants, Vincentz Network GmbH & Co KG, 2007, ISBN 978-3-87870-334-1,

... Shellac, a natural resin secreted by the scaly lac insect, has been used in India for centuries as a decorative coating for surfaces. The word lacquer in English is derived from the Sanskrit word laksha. which means one hundred thousand ...

- ↑ Donald Frederick Lach; Edwin J. Van Kley (1994-02-04), Asia in the making of Europe, Volume 2, Book 1, University of Chicago Press, 1971, ISBN 978-0-226-46730-6,

... Along with valuable woods from the East, the ancients imported lac, a resinous incrustation produced on certain trees by the puncture of the lac insect. In India, lac was used as sealing wax, dye and varnish ... Sanskrit, laksha; Hindi, lakh; Persian, lak; Latin, lacca. The Western word "lacquer" is derived from this term ...

- ↑ Thomas Brock; Michael Groteklaes; Peter Mischke (2000), European coatings handbook, Vincentz Network GmbH & Co KG, 2000, ISBN 978-3-87870-559-8,

... The word "lacquer" itself stems from the term "Laksha", from the pre-Christian, sacred Indian language Sanskrit, and originally referred to shellac, a resin produced by special insects ("lac insects") from the sap of an Indian fig tree ...

- 1 2 Wood Finishers Depot: Lacquer Sheen Archived October 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Britannica Online Encyclopedia: Oriental lacquer

- ↑ Major, John S., Sarah Queen, Andrew Meyer, Harold D. Roth, (2010), The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China, Columbia University Press, p. 219.

- 1 2 3 4 Webb, Marianne (2000). Lacquer: Technology and conservation. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7506-4412-9.

- ↑ Stark, Miriam T. (2005). Archaeology of Asia. Malden, MA : Blackwell Pub. Page 30. ISBN 1-4051-0213-6.

- ↑ Wang, Zhongshu. (1982). Han Civilization. Translated by K.C. Chang and Collaborators. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Page 80. ISBN 0-300-02723-0.

- ↑ Institute of the History of Natural Sciences and Chinese Academy of Sciences, ed. (1983). Ancient China's technology and science. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-8351-1001-3.

- ↑ Niimura, Noriyasu; Miyakoshi, Tetsuo (2003) Characterization of Natural Resin Films and Identification of Ancient Coating . J. Mass Spectrom. Soc. Jpn. 51, 440. JOI:JST.JSTAGE/massspec/51.439

Further reading

- Kimes, Beverly R., Editor. Clark, Henry A. (1996), The Standard Catalog of American Cars 1805–1945, Kraus Publications, ISBN 0-87341-428-4 p. 1050

- Paolo Nanetti (2006), Coatings from A to Z, Vincentz Verlag, Hannover, ISBN 3-87870-173-X - A concise compilation of technical terms. Attached is a register of all German terms with their corresponding English terms and vice versa, in order to facilitate its use as a means for technical translation from one language to the other.

- Webb, Marianne (2000), Lacquer: Technology and Conservation, Butterworth Heinemann, ISBN 0-7506-4412-5 — A Comprehensive Guide to the Technology and Conservation of Asian and European Lacquer

- Michiko, Suganuma. "Japanese lacquer".