Siege of La Rochelle

| Siege of La Rochelle (1627–1628) (Siège de La Rochelle 1627–1628) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Huguenot rebellions | |||||||

Cardinal Richelieu at the Siege of La Rochelle, Henri Motte, 1881. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Siege Army: 22,001 Toiras:1,200 |

La Rochelle: 27,000 civilians and soldiers Buckingham:80 ships 7,000 soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Siege Army: ? Toiras:500 killed |

La Rochelle:22,000 killed Buckingham: 5,000 killed | ||||||

The Siege of La Rochelle (French: Le Siège de La Rochelle, or sometimes Le Grand Siège de La Rochelle) was a result of a war between the French royal forces of Louis XIII of France and the Huguenots of La Rochelle in 1627–28. The siege marked the apex of the tensions between the Catholics and the Protestants in France, and ended with a complete victory for King Louis XIII and the Catholics.

Background

In the Edict of Nantes, Henry IV of France had given the Huguenots extensive rights. La Rochelle had become the stronghold of the French Huguenots, under its own governance. It was the centre of Huguenot seapower, and the strongest centre of resistance against the central government.[1] La Rochelle was, at this time, the second or third largest city in France, with over 30,000 inhabitants.

The assassination of Henry IV in 1610, and the advent of Louis XIII under the regency of Marie de' Medici, marked a return to pro-Catholic politics and a weakening of the position of the Protestants. The Duke Henri de Rohan and his brother Soubise started to organize Protestant resistance from that time, ultimately exploding into a Huguenot rebellion. In 1621, Louis XIII besieged and captured Saint-Jean d'Angély, and a Blockade of La Rochelle was attempted in 1621-1622, ending with a stalemate and the Treaty of Montpellier.

Again, Rohan and Soubise would take arms in 1625, ending with the capture of the Île de Ré in 1625 by Louis XIII. After these events, Louis XIII wished to subdue the Huguenots, and Louis' Chief Minister Cardinal Richelieu declared the suppression of the Huguenot revolt the first priority of the kingdom.

English intervention

The Anglo-French conflict followed the failure of the Anglo-French alliance of 1624, in which England had tried to find an ally in France against the power of the Habsburgs. In 1626, France under Richelieu actually concluded a secret peace with Spain, and disputes arose around Henrietta Maria's household. Furthermore, France was building the power of its Navy, leading the English to be convinced that France must be opposed "for reasons of state".[2]

In June 1626, Walter Montagu was sent to France to contact dissident noblemen, and from March 1627 attempted to organize a French rebellion. The plan was to send an English fleet to encourage rebellion, triggering a new Huguenot revolt by Duke Henri de Rohan and his brother Soubise.[2]

First La Rochelle expedition

Right image: English forces in the Siege of Saint-Martin-de-Ré.

On the first expedition, the English king Charles I sent a fleet of 80 ships, under his favourite George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, to encourage a major rebellion in La Rochelle. In June 1627 Buckingham organised a landing on the nearby island of Île de Ré with 6,000 men in order to help the Huguenots, thus starting the Anglo-French War of 1627, with the objective of controlling the approaches to La Rochelle, and of encouraging the rebellion in the city.

The city of La Rochelle initially refused to declare itself an ally of Buckingham, in a state of war against the crown of France, and effectively denied access to its harbour to Buckingham's fleet. An open alliance would only be declared in September at the time of the first fights between La Rochelle and Royal troops.

Although a Protestant stronghold, Île de Ré had not directly joined the rebellion against the king. On Île de Ré, the English under Buckingham tried to take the fortified city of Saint-Martin in the Siege of Saint-Martin-de-Ré (1627), but were repulsed after three months. Small French Royal boats managed to supply St Martin in spite of the English blockade. Buckingham ultimately ran out of money and support, and his army was weakened by diseases. After a last attack on Saint-Martin they were repulsed with heavy casualties, and left with their ships.

Siege

Meanwhile, in August 1627 Royal forces started to surround La Rochelle, with an army of 7,000 soldiers, 600 horses and 24 cannons, led by Charles of Angoulême. They started to reinforce fortifications at Bongraine (modern Les Minimes), and at the Fort Louis.

On September 10, the first cannon shots were fired by La Rochelle against Royal troops at Fort Louis, starting the third Huguenot rebellion. La Rochelle was the greatest stronghold among the Huguenot cities of France, and the centre of Huguenot resistance. Cardinal Richelieu acted as the commander of the besieging troops (during those times when the King was absent).

Once hostilities started, French engineers isolated the city with entrenchments 12 kilometres long, fortified by 11 forts and 18 redoubts. The surrounding fortifications were totally completed in April 1628, manned with an army of 30,000.

They also built with 4,000 workmen a 1,400-metre-long seawall, to block the seaward access to the city. The initial idea for blocking the channel leading to the harbour of La Rochelle in order to stop all supplies to the city came from the Italian engineer Pompeo Targone, but his structure was broken by the winter weather, before the idea was taken up by the Royal architect Clément Métezeau (also Metzeau),[3] in November 1627. The wall was built on top of a foundation made of sunken hulks, filled with rubble. French artillery was used against English ships that tried to supply the city.

Meanwhile, in southern France, Henri de Rohan attempted to raise a rebellion in order to relieve La Rochelle, but in vain. Until February, some ships were able to go through the seawall under construction, but after March this became impossible. The city was completely blocked, with the only hope coming from a possible intervention of an English fleet.

Foreign support for the French Crown

Dutch support

Altogether, the Roman Catholic government of France rented ships from the Protestant city of Amsterdam to conquer the Protestant city of La Rochelle. This resulted in a debate in the city council of Amsterdam as to whether the French soldiers should be allowed to have a Roman Catholic sermon on board of the Protestant Dutch ships. The result of the debate was that it was not allowed. The Dutch ships transported the French soldiers to La Rochelle. France was a Dutch ally in the war against the Habsburgs.

Spanish alliance

In the occasion of the Siege of La Rochelle, Spain manoeuvered towards the formation of a Franco-Spanish alliance against the common enemies that were the English, the Huguenots and the Dutch.[4] Richelieu accepted Spanish help, and a Spanish fleet of 30 to 40 warships was sent from Cadiz to the Gulf of Morbihan as an affirmation of strategic support,[4] arriving three weeks after the departure of Buckingham from Île de Ré. At one point, the Spanish fleet anchored in front of La Rochelle, but did not engage in actual operations against the city.

English relief efforts

England attempted to send two more fleets to relieve La Rochelle.

Second La Rochelle expedition

The second one, led by William Feilding, Earl of Denbigh, left on April 1628, but returned without a fight to Portsmouth, as Denbigh said that he had no commission to hazard the king's ships in a fight, and returned shamefully to Portsmouth.[5]

Third La Rochelle expedition

A third fleet was dispatched under the Admiral of the Fleet, the Earl of Lindsey in August 1628,[5] consisting in 29 warships and 31 merchantmen.[6] In September 1628, the English fleet tried to relieve the city. After bombarding French positions and trying to force the sea wall in vain, the English fleet had to withdraw. Following this last disappointment, the city surrendered on October 28, 1628.

Epilogue

Residents of La Rochelle had resisted for 14 months, under the leadership of the mayor Jean Guitton and with the gradually diminishing help from England. During the siege, the population of La Rochelle decreased from 27,000 to 5,000 due to casualties, famine, and disease.

Surrender was unconditional. By the terms of the Peace of Alais, the Huguenots lost their territorial, political and military rights, but retained the religious freedom granted by the Edict of Nantes. However, they were left at the mercy of the monarchy, unable to resist later when Louis XIV abolished the Edict of Nantes altogether and embarked on active persecution.

Aside from its religious aspect, the result of Siege of La Rochelle marks an important stage in the creation of a strong central government in France, in actual control of its entire territory and intolerant of any regional defiance of its rule. In the immediate aftermath this was manifested in growth of absolute monarchy, but had long-term effects upon all later French regimes up to the present.

The French philosopher Descartes is known to have visited the scene of the siege in 1627.

The siege was depicted in detail by numerous artists, such as Jacques Callot.

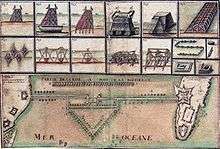

Birdeye views by Jacques Callot

The Siege of La Rochelle, plate 1.

The Siege of La Rochelle, plate 1. Plate 2: the sea wall and Les Minimes.

Plate 2: the sea wall and Les Minimes. Plate 3: Aytré.

Plate 3: Aytré.

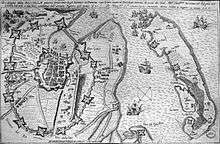

Maps by Jacques Callot

Plate 4: area of La Pallice and Laleu.

Plate 4: area of La Pallice and Laleu. Plate 5: overview of La Rochelle surrounded.

Plate 5: overview of La Rochelle surrounded. Plate 6.

Plate 6.

Others

City of La Rochelle and fortifications during the siege, anonymous, 17th century, Versailles.

City of La Rochelle and fortifications during the siege, anonymous, 17th century, Versailles. Siege of La Rochelle by Claude Lorrain, Le Louvre.

Siege of La Rochelle by Claude Lorrain, Le Louvre. The Siege of La Rochelle by Jacques Callot, with the English fleet of the Earl of Lindsey approaching.

The Siege of La Rochelle by Jacques Callot, with the English fleet of the Earl of Lindsey approaching.

Numismatics

Around the time of the siege, a series of propaganda coins were cast to describe the stakes of the siege, and then commemorate the Royal victory. These coins depict the siege in symbolic ways, showing the city and the English effort in a poor light, while putting an advantageous light on Royal might.[7]

Lucerna Impiorum Extinguetur ("The impious light must be extinguished"), 1626.

Lucerna Impiorum Extinguetur ("The impious light must be extinguished"), 1626. Two dogs in the water around the reflection of a crown 1627.

Two dogs in the water around the reflection of a crown 1627. Dragon (La Rochelle) and lion (England) mastered under Royal arm, 1628.

Dragon (La Rochelle) and lion (England) mastered under Royal arm, 1628. Lionness captured behind a seawall, 1628.

Lionness captured behind a seawall, 1628. Sea monster cut in two by the seawall, 1628.

Sea monster cut in two by the seawall, 1628. English snail pierced by an arrow on a raft, Esto Domi ("Go Home"), 1628.

English snail pierced by an arrow on a raft, Esto Domi ("Go Home"), 1628. Vanquished English ship, Tellus decepit et Unda, 1629.

Vanquished English ship, Tellus decepit et Unda, 1629.

Siege in fiction and film

The siege forms the historical background for the novel The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas, père and the book's numerous adaptations to stage, screen, comics and video game.

The 11th book of Robert Merle's Fortune de France series, La Gloire et les perils, deals entirely with the siege of La Rochelle.

In Lawrence Norfolk's 1991 novel, Lemprière's Dictionary, the siege is the central cause of events — entirely fictional — 160 years later in London around the writing of John Lemprière's Classical Dictionary containing a full Account of all the Proper Names mentioned in Ancient Authors.

Taylor Caldwell writes about the siege in great detail in her 1943 novel The Arm and the Darkness; however she has as its commander the fictional Huguenot nobleman Arsene de Richepin, one of the central characters of the book.

Notes

- ↑ Warfare at sea, 1500-1650: maritime conflicts and the transformation of Europe by Glete J Staff, Jan Glete Routledge, 2002 ISBN 0-203-02456-7 p.178

- 1 2 Historical dictionary of Stuart England, 1603-1689 by Ronald H. Fritze, p.203

- ↑ Duffy, p.118

- 1 2 The Thirty Years' War by Geoffrey Parker, p.74

- 1 2 An apprenticeship in arms by Roger Burrow Manning, p.119

- ↑ Ships, money, and politics by Kenneth R. Andrews, p.150

- ↑ Musée d'Orbigny-Bernon exhibit

References

- Christopher Duffy Siege warfare: the fortress in the early modern world, 1494-1660 Routledge, 1979 ISBN 0-7100-8871-X

Coordinates: 46°10′00″N 1°09′00″W / 46.1667°N 1.1500°W