Newline

In computing, a newline, also known as a line ending, end of line (EOL), or line break, is a special character or sequence of characters signifying the end of a line of text and the start of a new line. The actual codes representing a newline vary across operating systems, which can be a problem when exchanging text files between systems with different newline representations.

The concepts of line feed (LF) and carriage return (CR) are closely associated, and can be either considered separately or together. In the physical media of typewriters and printers, two axes of motion, "down" and "across", are needed to create a new line on the page. Although the design of a machine (typewriter or printer) must consider them separately, the abstract logic of software can combine them together as one event. This is why a newline in character encoding can be defined as LF and CR combined into one (known variously as CR+LF, CRLF, LF+CR, or LFCR).

Some character sets provide a separate newline character code. EBCDIC, for example, provides an NL character code in addition to the CR and LF codes. Unicode, in addition to providing the ASCII CR and LF control characters, also provides a "next line" (NEL) control code, as well as control codes for "line separator" and "paragraph separator" markers.

Two ways to view newlines, both of which are self-consistent, are that newlines either separate lines or that they terminate lines. If a newline is considered a separator, there will be no newline after the last line of a file. Some programs have problems processing the last line of a file if it is not terminated by a newline. On the other hand, programs that expect newline to be used as a separator will interpret a final newline as starting a new (empty) line. Conversely, if a newline is considered a terminator, all text lines including the last are expected to be terminated by a newline. If the final character sequence in a text file is not a newline, the final line of the file may be considered to be an improper or incomplete text line, or the file may be considered to be improperly truncated.

In text intended primarily to be read by humans using software which implements the word wrap feature, a newline character typically only needs to be stored if a line break is required independent of whether the next word would fit on the same line, such as between paragraphs and in vertical lists. Therefore, in the logic of word processing, newline is used as a paragraph break and is known as a "hard return", in contrast to "soft returns" which are dynamically created to implement word wrapping and are changeable with each display instance. A separate control character called "manual line break" exists for forcing line breaks inside a single paragraph.

Representations

Software applications and operating systems usually represent a newline with one or two control characters:

- Systems based on ASCII or a compatible character set use either LF (Line feed, '\n', 0x0A, 10 in decimal) or CR (Carriage return, '\r', 0x0D, 13 in decimal, displayed as "^M" in some editors) individually, or CR followed by LF (CR+LF, '\r\n', 0x0D0A). These characters are based on printer commands: The line feed indicated that one line of paper should feed out of the printer thus instructed the printer to advance the paper one line, and a carriage return indicated that the printer carriage should return to the beginning of the current line. Some rare systems, such as QNX before version 4, used the ASCII RS (record separator, 0x1E, 30 in decimal) character as the newline character.

- LF: Unix and Unix-like systems (Linux, OS X, FreeBSD, Multics, AIX, Xenix, etc.), BeOS, Amiga, RISC OS, and others[1]

- CR+LF: Microsoft Windows, DOS (MS-DOS, PC DOS, etc.), DEC TOPS-10, RT-11, CP/M, MP/M, Atari TOS, OS/2, Symbian OS, Palm OS, Amstrad CPC, and most other early non-Unix and non-IBM OSes

- CR: Commodore 8-bit machines, Acorn BBC, ZX Spectrum, TRS-80, Apple II family, Oberon, the classic Mac OS up to version 9, MIT Lisp Machine and OS-9

- RS: QNX pre-POSIX implementation

- 0x9B: Atari 8-bit machines using ATASCII variant of ASCII (155 in decimal)

- LF+CR: Acorn BBC and RISC OS spooled text output.

- EBCDIC systems—mainly IBM mainframe systems, including z/OS (OS/390) and i5/OS (OS/400)—use NL (New Line, 0x15)[2] as the character combining the functions of line-feed and carriage-return. The equivalent UNICODE character is called NEL (Next Line). Note that EBCDIC also has control characters called CR and LF, but the numerical value of LF (0x25) differs from the one used by ASCII (0x0A). Additionally, some EBCDIC variants also use NL but assign a different numeric code to the character.

- Operating systems for the CDC 6000 series defined a newline as two or more zero-valued six-bit characters at the end of a 60-bit word. Some configurations also defined a zero-valued character as a colon character, with the result that multiple colons could be interpreted as a newline depending on position.

- ZX80 and ZX81, home computers from Sinclair Research Ltd used a specific non-ASCII character set with code NEWLINE (0x76, 118 decimal) as the newline character.

- OpenVMS uses a record-based file system, which stores text files as one record per line. In most file formats, no line terminators are actually stored, but the Record Management Services facility can transparently add a terminator to each line when it is retrieved by an application. The records themselves could contain the same line terminator characters, which could either be considered a feature or a nuisance depending on the application.

- Fixed line length was used by some early mainframe operating systems. In such a system, an implicit end-of-line was assumed every 72 or 80 characters, for example. No newline character was stored. If a file was imported from the outside world, lines shorter than the line length had to be padded with spaces, while lines longer than the line length had to be truncated. This mimicked the use of punched cards, on which each line was stored on a separate card, usually with 80 columns on each card, often with sequence numbers in columns 73–80. Many of these systems added a carriage control character to the start of the next record; this could indicate whether the next record was a continuation of the line started by the previous record, or a new line, or should overprint the previous line (similar to a CR). Often this was a normal printing character such as "#" that thus could not be used as the first character in a line. Some early line printers interpreted these characters directly in the records sent to them.

Most textual Internet protocols (including HTTP, SMTP, FTP, IRC, and many others) mandate the use of ASCII CR+LF ('\r\n', 0x0D 0x0A) on the protocol level, but recommend that tolerant applications recognize lone LF ('\n', 0x0A) as well. Despite the dictated standard, many applications erroneously use the C newline escape sequence '\n' (LF) instead of the correct combination of carriage return escape and newline escape sequences '\r\n' (CR+LF) (see section Newline in programming languages below). This accidental use of the wrong escape sequences leads to problems when trying to communicate with systems adhering to the stricter interpretation of the standards instead of the suggested tolerant interpretation. One such intolerant system is the qmail mail transfer agent that actively refuses to accept messages from systems that send bare LF instead of the required CR+LF.[3]

FTP has a feature to transform newlines between CR+LF and the native encoding of the system (e.g., LF only) when transferring text files. This feature must not be used on binary files. Often binary files and text files are recognised by checking their filename extension; most command-line FTP clients have an explicit command to switch between binary and text mode transfers.

Unicode

The Unicode standard defines a number of characters that conforming applications should recognize as line terminators:[4]

- LF: Line Feed, U+000A

- VT: Vertical Tab, U+000B

- FF: Form Feed, U+000C

- CR: Carriage Return, U+000D

- CR+LF: CR (U+000D) followed by LF (U+000A)

- NEL: Next Line, U+0085

- LS: Line Separator, U+2028

- PS: Paragraph Separator, U+2029

This may seem overly complicated compared to an approach such as converting all line terminators to a single character, for example LF. However, Unicode was designed to preserve all information when converting a text file from any existing encoding to Unicode and back. Therefore, Unicode should contain characters included in existing encodings. NEL is included in EBCDIC with code (0x15). NEL is also a control character in the C1 control set.[5] As such, it is defined by ECMA 48,[6] and recognized by encodings compliant with ISO-2022 (which is equivalent to ECMA 35).[7] C1 control set is also compatible with ISO-8859-1. The approach taken in the Unicode standard allows round-trip transformation to be information-preserving while still enabling applications to recognize all possible types of line terminators.

Recognizing and using the newline codes greater than 0x7F is not often done. They are multiple bytes in UTF-8, and the code for NEL has been used as the ellipsis ('…') character in Windows-1252. For instance:

- ECMAScript[8] accepts LS and PS as line breaks, but considers U+0085 (NEL) white space, not a line break.

- Microsoft Windows 2000 does not treat any of NEL, LS, or PS as line-break in the default text editor Notepad

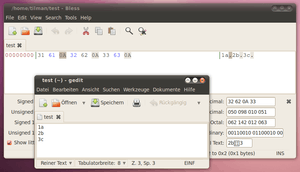

- On Linux, a popular editor, gedit, treats LS and PS as newlines but does not for NEL.

- YAML[9] no longer recognizes them as special, in order to be compatible with JSON.

- JSON treats LS and PS inside a String as letter while ECMAScript/Javascript treats them as new line and shows an error

The Unicode characters U+2424 (SYMBOL FOR NEWLINE, ), U+23CE (RETURN SYMBOL, ⏎), U+240D (SYMBOL FOR CARRIAGE RETURN, ␍) and U+240A (SYMBOL FOR LINE FEED, ␊) are intended for presenting a user-visible character to the reader of the document, and are thus not recognized themselves as a newline.

History

ASCII was developed simultaneously by the ISO and the ASA, the predecessor organization to ANSI. During the period of 1963–1968, the ISO draft standards supported the use of either CR+LF or LF alone as a newline, while the ASA drafts supported only CR+LF.

The sequence CR+LF was in common use on many early computer systems that had adopted Teletype machines, typically a Teletype Model 33 ASR, as a console device, because this sequence was required to position those printers at the start of a new line. The separation of newline into two functions concealed the fact that the print head could not return from the far right to the beginning of the next line in one-character time. That is why the sequence was always sent with the CR first. A character printed after a CR would often print as a smudge, on-the-fly in the middle of the page, while it was still moving the carriage back to the first position. "The solution was to make the newline two characters: CR to move the carriage to column one, and LF to move the paper up."[10] In fact, it was often necessary to send extra characters (extraneous CRs or NULs, which are ignored) to give the print head time to move to the left margin. Even many early video displays required multiple character times to scroll the display.

On these systems, text was often routinely composed to be compatible with these printers, since the concept of device drivers hiding such hardware details from the application was not yet well developed; applications had to talk directly to the Teletype machine and follow its conventions. Most minicomputer systems from DEC used this convention. CP/M used it as well, to print on the same terminals that minicomputers used. From there MS-DOS (1981) adopted CP/M's CR+LF in order to be compatible, and this convention was inherited by Microsoft's later Windows operating system.

The Multics operating system began development in 1964 and used LF alone as its newline. Multics used a device driver to translate this character to whatever sequence a printer needed (including extra padding characters), and the single byte was much more convenient for programming. The seemingly more obvious choice of CR was not used, as a plain CR provided the useful function of overprinting one line with another to create boldface and strikethrough effects, and thus it was useful to not translate it. Unix followed the Multics practice, and later systems followed Unix.

In programming languages

To facilitate the creation of portable programs, programming languages provide some abstractions to deal with the different types of newline sequences used in different environments.

The C programming language provides the escape sequences '\n' (newline) and '\r' (carriage return). However, these are not required to be equivalent to the ASCII LF and CR control characters. The C standard only guarantees two things:

- Each of these escape sequences maps to a unique implementation-defined number that can be stored in a single char value.

- When writing a file in text mode, '\n' is transparently translated to the native newline sequence used by the system, which may be longer than one character. When reading in text mode, the native newline sequence is translated back to '\n'. In binary mode, no translation is performed, and the internal representation produced by '\n' is output directly.

On Unix platforms, where C originated, the native newline sequence is ASCII LF (0x0A), so '\n' was simply defined to be that value. With the internal and external representation being identical, the translation performed in text mode is a no-op, and Unix has no notion of text mode or binary mode. This has caused many programmers who developed their software on Unix systems simply to ignore the distinction completely, resulting in code that is not portable to different platforms.

The C library function fgets() is best avoided in binary mode because any file not written with the UNIX newline convention will be misread. Also, in text mode, any file not written with the system's native newline sequence (such as a file created on a UNIX system, then copied to a Windows system) will be misread as well.

Another common problem is the use of '\n' when communicating using an Internet protocol that mandates the use of ASCII CR+LF for ending lines. Writing '\n' to a text mode stream works correctly on Windows systems, but produces only LF on Unix, and something completely different on more exotic systems. Using "\r\n" in binary mode is slightly better.

Many languages, such as C++, Perl,[11] and Haskell provide the same interpretation of '\n' as C.

Java, PHP,[12] and Python[13] provide the '\r\n' sequence (for ASCII CR+LF). In contrast to C, these are guaranteed to represent the values U+000D and U+000A, respectively.

The Java I/O libraries do not transparently translate these into platform-dependent newline sequences on input or output. Instead, they provide functions for writing a full line that automatically add the native newline sequence, and functions for reading lines that accept any of CR, LF, or CR+LF as a line terminator (see BufferedReader.readLine()). The System.lineSeparator() method can be used to retrieve the underlying line separator.

Example:

String eol = System.lineSeparator();

String lineColor = "Color: Red" + eol;

Python permits "Universal Newline Support" when opening a file for reading, when importing modules, and when executing a file.[14]

Some languages have created special variables, constants, and subroutines to facilitate newlines during program execution. In some languages such as PHP and Perl, double quotes are required to perform escape substitution for all escape sequences, including '\n' and '\r'. In PHP, to avoid portability problems, newline sequences should be issued using the PHP_EOL constant.[15]

Example in C#:

string eol = Environment.NewLine;

string lineColor = "Color: Red" + eol;

string eol2 = "\n";

string lineColor2 = "Color: Blue" + eol2;

Common problems

The different newline conventions often cause text files that have been transferred between systems of different types to be displayed incorrectly. For example, files originating on Unix or Apple Macintosh systems may appear as a single long line on some programs running on Microsoft Windows. Conversely, when viewing a file originating from a Windows computer on a Unix system, the extra CR may be displayed as ^M or <cr> at the end of each line or as a second line break.

The problem can be hard to spot if some programs handle the foreign newlines properly while others do not. For example, a compiler may fail with obscure syntax errors even though the source file looks correct when displayed on the console or in an editor. On a Unix system, the command cat -v myfile.txt will send the file to stdout (normally the terminal) and make the ^M visible, which can be useful for debugging. Modern text editors generally recognize all flavours of CR+LF newlines and allow users to convert between the different standards. Web browsers are usually also capable of displaying text files and websites which use different types of newlines.

Even if a program supports different newline conventions, these features are often not sufficiently labeled, described, or documented. Typically a menu or combo-box enumerating different newline conventions will be displayed to users without an indication if the selection will re-interpret, temporarily convert, or permanently convert the newlines. Some programs will implicitly convert on open, copy, paste, or save—often inconsistently.

The File Transfer Protocol can automatically convert newlines in files being transferred between systems with different newline representations when the transfer is done in "ASCII mode". However, transferring binary files in this mode usually has disastrous results: any occurrence of the newline byte sequence—which does not have line terminator semantics in this context, but is just part of a normal sequence of bytes—will be translated to whatever newline representation the other system uses, effectively corrupting the file. FTP clients often employ some heuristics (for example, inspection of filename extensions) to automatically select either binary or ASCII mode, but in the end it is up to users to make sure their files are transferred in the correct mode. If there is any doubt as to the correct mode, binary mode should be used, as then no files will be altered by FTP, though they may display incorrectly.[16]

Conversion utilities

Text editors are often used for converting a text file between different newline formats; most modern editors can read and write files using at least the different ASCII CR/LF conventions. The standard Windows editor Notepad is not one of them (although WordPad and the MS-DOS Editor are).

Editors are often unsuitable for converting larger files. For larger files (on Windows NT/2000/XP) the following command is often used:

D:\>TYPE unix_file | FIND /V "" > dos_file

On many Unix systems, the dos2unix (sometimes named fromdos or d2u) and unix2dos (sometimes named todos or u2d) utilities are used to translate between ASCII CR+LF (DOS/Windows) and LF (Unix) newlines. Different versions of these commands vary slightly in their syntax. However, the tr command is available on virtually every Unix-like system and is used to perform arbitrary replacement operations on single characters. A DOS/Windows text file can be converted to Unix format by simply removing all ASCII CR characters with

$ tr -d '\r' < inputfile > outputfile

or, if the text has only CR newlines, by converting all CR newlines to LF with

$ tr '\r' '\n' < inputfile > outputfile

Reverse and partial line feeds

RI, (U+008D REVERSE LINE FEED,[17] ISO/IEC 6429 8D, decimal 141) is used to move the printing position back one line (by reverse feeding the paper, or by moving a display cursor up one line) so that other characters may be printed over existing text. This may be done to make them bolder, or to add underlines, strike-throughs or other characters such as diacritics.

Similarly, PLD (U+008B PARTIAL LINE FORWARD, decimal 139) and PLU (U+008C PARTIAL LINE BACKWARD, decimal 140) can be used to advance or reverse the text printing position by some fraction of the vertical line spacing (typically, half). These can be used in combination for subscripts (by advancing and then reversing) and superscripts (by reversing and then advancing), and may also be useful for printing diacrtitics.

See also

References

- ↑ "ASCII Chart".

- ↑ IBM System/360 Reference Data Card, Publication GX20-1703, IBM Data Processing Division, White Plains, NY

- ↑ cr.yp.to

- ↑ Unicode Standard Annex #14 UNICODE LINE BREAKING ALGORITHM

- ↑ http://kikaku.itscj.ipsj.or.jp/ISO-IR/077.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ecma-international.org/publications/files/ECMA-ST/Ecma-048.pdf Control Functions for Coded Character Sets, June 1991

- ↑ http://www.ecma-international.org/publications/files/ECMA-ST/Ecma-035.pdf Character Code Structure and Extension Techniques 1971. Three further editions in 1980, 1982, and 1985, Décembre 1994

- ↑ "ECMAScript Language Specification 5th edition" (PDF). ECMA International. December 2009. p. 15. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ YAML Ain't Markup Language (YAML™) Version 1.2

- ↑ Qualline, Steve (2001). Vi Improved - Vim (PDF). Sams. p. 120. ISBN 9780735710016.

- ↑ binmode - perldoc.perl.org

- ↑ Strings (PHP Manual)

- ↑ Lexical analysis (Python v3.0.1 documentation)

- ↑ What's new in Python 2.3

- ↑ PHP: Predefined Constants

- ↑ "File Transfer".

When in doubt, transfer in binary mode.

- ↑ "C1 Controls and Latin-1 Supplement" (PDF). unicode.org. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

External links

- The Unicode reference, see paragraph 5.8 in Chapter 5 of the Unicode 4.0 standard (PDF)

- The [NEL] Newline Character

- The End of Line Puzzle

- "Understanding Newlines" on O'Reilly-Net - an article by Xavier Noria.

- "The End-of-Line Story"