Ku Klux Klan members in United States politics

Some notable figures in U.S. national politics were members of the Ku Klux Klan before taking office, and in some cases may have still been members while in office. Others may or may not have been members.

Politicians who were active in the Klan at some time

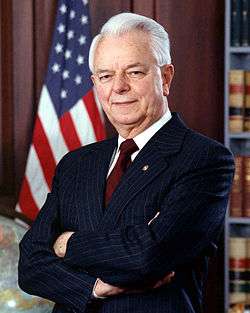

Robert Byrd

Robert C. Byrd, a Democrat, was a recruiter for the Klan while in his 20s and 30s, rising to the title of Kleagle and Exalted Cyclops of his local chapter. After leaving the group, Byrd spoke in favor of the Klan during his early political career. Though he claimed to have left the organization in 1943, Byrd wrote a letter in 1946 to the group's Imperial Wizard stating "The Klan is needed today as never before, and I am anxious to see its rebirth here in West Virginia." Byrd attempted to explain or defend his former membership in the Klan in his 1958 U.S. Senate campaign when he was 41 years old.[1] Byrd, a Democrat, eventually became his party leader in the Senate. Byrd later said joining the Klan was his "greatest mistake." The NAACP gave him a 100% rating on their issues during the 108th Congress.[2] However, in a 2001 incident Byrd repeatedly used the phrase "white niggers" on a national television broadcast.[3]

Hugo Black

In 1921, Hugo Black successfully defended E. R. Stephenson in his trial for the murder of a Catholic priest, Fr. James E. Coyle. Black, a Democrat, joined the Ku Klux Klan shortly after, in order to gain votes from the anti-Catholic element in Alabama. He built his winning Senate campaign around multiple appearances at KKK meetings across Alabama. Late in life Black told an interviewer:

at that time, I was joining every organization in sight!...In my part of Alabama, the Klan was not engaged in unlawful activities....The general feeling in the community was that if responsible citizens didn't join the Klan it would soon become dominated by the less responsible members.[4]

News of his membership was a secret until shortly after he was confirmed as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Black later said that joining the Klan was a mistake, but he went on to say, "I would have joined any group if it helped get me votes."[5][6]

Theodore G. Bilbo

Theodore G. Bilbo, a Democrat and United States Senator from Mississippi, revealed his membership in the Ku Klux Klan in an interview on the radio program Meet the Press. He said, "No man can leave the Klan. He takes an oath not to do that. Once a Ku Klux, always a Ku Klux."[7]

Rice W. Means

Rice W. Means, a Republican United States Senator from Colorado, was a member of the Klan in Colorado. He served a three-year term in Congress before losing renomination to Republican Charles W. Waterman in the 1926 election.[8][9]

Clarence Morley

Clarence Morley was a Republican and the governor of Colorado from 1925 to 1927. He was a KKK member and a strong supporter of Prohibition. He tried to ban the Catholic Church from using sacramental wine and attempted to have the University of Colorado fire all Jewish and Catholic professors.[9][10][11][12]

Bibb Graves

Bibb Graves, a Democrat, who was the 38th Governor of Alabama. He lost his first campaign for governor in 1922, but four years later, with the secret endorsement of the Ku Klux Klan, he was elected to his first term as governor. Graves was almost certainly the Exalted Cyclops (chapter president) of the Montgomery chapter of the Klan. Graves, like Hugo Black, used the strength of the Klan to further his electoral prospects.[13]

Clifford Walker

Clifford Walker, a Democrat and the 64th Governor of Georgia, was revealed to be a Klan member by the press in 1924.[14]

George Gordon

George Gordon, a Democrat and Congressman for Tennessee's 10th congressional district, became one of the Klan's first members. In 1867, Gordon became the Klan's first Grand Dragon for the Realm of Tennessee, and wrote its Precept, a book describing its organization, purpose, and principles.

John Brown Gordon

John Brown Gordon, a Democrat and the United States Senator for Georgia, was almost certainly a member of the Klan, possibly the titular head for the state.[15]

John Clinton Porter

John Clinton Porter, a Democrat, was a member of the Klan in the early 1920s, but was no longer a member when he was elected mayor of Los Angeles in 1928.[16]

David Duke

David Duke, a politician who ran in both Democrat and Republican presidential primaries, was openly involved in the leadership of the Ku Klux Klan.[17] He was founder and Grand Wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in the mid-1970s; he re-titled his position as "National Director" and said that the KKK needed to "get out of the cow pasture and into hotel meeting rooms". He left the organization in 1980. He ran for president in the 1988 Democratic presidential primaries. In 1989 Duke switched political parties from Democrat to Republican.[18] In 1989, he became a member of the Louisiana State Legislature from the 81st district, and was Republican Party chairman for St. Tammany Parish.[19]

Benjamin F. Stapleton

Benjamin F. Stapleton, a Democrat, was mayor of Denver in the 1920s-1940s. He was a Klan member in the early 1920s and appointed fellow Klansmen to positions in municipal government.[20]

Alleged members of the Klan

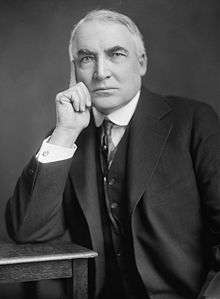

Warren G. Harding

One source claims Warren G. Harding, a Republican, was a Ku Klux Klan member while President. The claim is based on a third-hand account of a second-hand recollection in 1985 of a deathbed statement made sometime in the late 1940s concerning an incident in the early 1920s. Independent investigations have turned up many contradictions and no supporting evidence. Historians reject the claim and note that Harding in fact publicly fought and spoke against the Klan.

Wyn Craig Wade states Harding's membership as fact and gives a detailed account of a secret swearing-in ceremony in the White House, based on a private communication he received in 1985 from journalist Stetson Kennedy. Kennedy, in turn had, along with Elizabeth Gardner, tape recorded some time in the "late 1940s" a deathbed confession of former Imperial Klokard Alton Young. Young claimed to have been a member of the "Presidential Induction Team". Young also said on his deathbed that he had repudiated racism.[21][22]

Wade states that "This matter was a major issue in letters sent to Coolidge during the 1924 election", and gives a reference to "Case File 28, Calvin Coolidge papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress". In this file there is a letter from Wizard Edward Young Clarke to President Calvin Coolidge on 27 December 1923, charging Wizard Hiram W. Evens with trying to turn the Klan into a "cheap political machine".

In their 2005 book Freakonomics, University of Chicago economist Steven D. Levitt and journalist Stephen J. Dubner alluded to Warren Harding's possible Klan affiliation. However, in a New York Times Magazine Freakonomics column, entitled "Hoodwinked? Does it matter if an activist who exposes the inner workings of the Ku Klux Klan isn't open about how he got those secrets?", Dubner and Levitt said that they no longer accepted Stetson Kennedy's testimony about Harding and the Klan.[23]

Primary source material on file at the Ohio Historical Society in Columbus does not contain evidence of Harding's alleged membership in the Klan. Primary source material on file at the Marion County (Ohio) Historical Society (Warren G. Harding Collection) also does not confirm or indicate any involvement in the Klan, nor support the idea of Harding’s alleged Klan membership. The Site Administrator of the Harding Home Museum (Ohio Historical Society property) in Marion, Ohio, draws a relationship between Harding's alleged Klan activities and the rumors stirred up after the President died in 1923 and Mrs. Harding in 1924.

The 1920 Republican Party platform, which essentially expressed Harding's political philosophy, calls for Congress to pass laws combating lynching.[24] Harding was the first American President to publicly denounce lynching and did so in a landmark 21 October 1921 speech in Birmingham, Alabama, which was covered in the national press. Harding also vigorously supported an anti-lynching bill in Congress during his term in the White House. While the bill was defeated in the Senate, such activities would be in direct conflict with Klan membership.

In his book, The Strange Deaths of President Harding, historian Robert Ferrell says he was unable to find any records of any such "ceremony" in which Harding was brought into the Klan in the White House. John Dean, in his 2004 book Warren Harding, also could find no proof of Klan membership or activity on the part of Harding. Review of the personal records of Harding's Personal White House Secretary, George Christian Jr., also do not support the contention that Harding received members of the Klan while in office. Appointment books maintained in the White House, detailing President Harding's daily schedules, do not show any such event.

Payne argues that the Klan was so angry with Harding's attacks on the KKK that it originated and spread the false rumor that he was a member.[25]

Carl S. Anthony, biographer of Harding's wife, found no such proof of Harding's membership in the Klan. He does however discuss the events leading up to the period when the alleged Klan ceremony was held in June 1923:

[K]nowing that the some branches of the Shriners were anti-Catholic and in that sense sympathetic to the Ku Klax Klan and that the Klan itself was holding a demonstration less than a half mile from Washington, Harding censured hate groups in his Shriners speech. The press "considered [it] a direct attack" on the Klan, particularly in light of his criticism weeks earlier of "factions of hatred and prejudice and violence [that] challeng[ed] both civil and religious liberty".[26]

In 2005, The Straight Dope presented a summary of many of these arguments against Harding's membership, and noted that, while it might have been politically expedient for him to join the KKK in public, to do it in private would have been of no benefit to him.[27]

Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman, the Democratic politician who became president in 1945, was accused by opponents of having dabbled with the Klan briefly. In 1924, he was a judge in Jackson County, Missouri. Truman was up for reelection, and his friends Edgar Hinde and Spencer Salisbury advised him to join the Klan. The Klan was politically powerful in Jackson County, and two of Truman's opponents in the Democratic primary had Klan support. Truman refused at first, but paid the Klan's $10 membership fee, and a meeting with a Klan officer was arranged.[28]

According to Salisbury's version of the story, Truman was inducted, but afterward "was never active; he was just a member who wouldn't do anything". Salisbury, however, told the story after he became Truman's bitter enemy, so historians are reluctant to believe his claims.[29]

According to Hinde and Truman's accounts, the Klan officer demanded that Truman pledge not to hire any Catholics or Jews if he was reelected. Truman refused, and demanded the return of his $10 membership fee; most of the men he had commanded in World War I had been local Irish Catholics.[30]

Truman had at least one other strong reason to object to the anti-Catholic requirement, which was that the Catholic Pendergast family, which operated a political machine in Jackson County, were his patrons; Pendergast family lore has it that Truman was originally accepted for patronage without even meeting him, on the basis of his family background plus the requirement that he was not a member of any anti-Catholic organization such as the Klan.[31] The Pendergast faction of the Democratic Party was known as the "Goats", as opposed to the rival Shannon machine's "Rabbits". The battle lines were drawn when Truman put only Goats on the county payroll,[32] and the Klan began encouraging voters to support Protestant, "100% American" candidates, allying itself against Truman and with the Rabbits, while Shannon instructed his people to vote Republican in the election, which Truman lost.[33] Truman later claimed that the Klan "threatened to kill me, and I went out to one of their meetings and dared them to try", speculating that if Truman's armed friends had shown up earlier, violence might have resulted. However, biographer Alonzo Hamby believes that this story, which is not supported by any recorded facts, was a confabulation based on a meeting with a hostile and menacing group of Democrats that contained many Klansmen, showing Truman's "Walter Mitty-like tendency […] to rewrite his personal history".[34] Sympathetic observers see Truman's flirtation with the Klan as a momentary aberration, point out that his close friend and business partner Eddie Jacobson was Jewish, and say that in later years Truman's presidency marked the first significant improvement in the federal government's record on civil rights since the post-Reconstruction nadir marked by the Wilson administration.[35]

See also

References

- ↑ Pianin, Eric. "A Senator's Shame." Washington Post 19 June 2005.

- ↑ "NAACP Civil Rights Federal Legislative Report Card: 108th Congress" (PDF). naacp.org.

- ↑ "Breaking News, Daily News and Videos". CNN. March 4, 2001.

- ↑ Roger K, Newman, Hugo Black: a biography (1997) p 97.

- ↑ Ball, Hugo L. Black pp 16, 50.

- ↑ Hugo Black's membership was the subject of Ray Sprigle's 1938 series of articles in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, for which Sprigle won the Pulitzer Prize.

- ↑ Robert L. Fleegler, "Theodore G. Bilbo and the Decline of Public Racism, 1938-1947", The Journal of Mississippi History, Spring 2006

- ↑ Waterman, Edgar Francis; Jacobus, Donald Lines (1954). "Charles Winfield [Waterman]". The Waterman Family. 3. New Haven, Connecticut: E. F. Waterman. p. 187. OCLC 2023265.

- 1 2 Colorado Governors: Clarence Morley. State of Colorado collections. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- ↑ Bartels, Lynn (March 4, 2014). "The Spot: Bob Beauprez bypasses KKK member, attacks Hickenlooper as most 'extreme' governor". Denver Post (blog).

- ↑ Littwin, Mike (March 4, 2014). "The gov's race: There's extreme, and then there's extreme". Colorado Independent.

- ↑ Degette, Cara (January 9, 2009). "When Colorado was Klan country". Colorado Independent.

- ↑ Glenn Feldman,Politics, Society and the Klan in Alabama, 1915-1949 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999); Rice, 138.

- ↑ "Georgia: Governor Clifford Mitchell Walker". National Governors Association. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- ↑ New Georgia Encyclopedia. Biographical sketches in the references by Deserino, Eicher, and Warner make no mention of Klan involvement. Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. Francis Parkman Prize edition. New York: History Book Club, 2005. ISBN 0-965-72701-7. First published 1988 by HarperCollins, p. 433: a "prominent Klansman".

- ↑ Kevin Starr, Material Dreams: Southern California through the 1920's (1990), pp 138-139.

- ↑ "David Duke On the KKK". adl.org.

- ↑ Zatarain, Michael (July 1990). Michael Zatarain, David Duke: Evolution of a Klansman. Google Books. ISBN 978-0-88289-817-9. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ↑ "David Duke: In His Own Words - Introduction". adl.org.

- ↑ Goldberg, R. (1981). Hooded Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Colorado. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- ↑ Kennedy, "Woody Guthrie: Natural born anti-fascist", retrieved 9 September 2005.

- ↑ Wade 1987, 165, 477.

- ↑ New York Times Magazine, January 8, 2006, pp. 26–28

- ↑ Republican Party Platform of 1920 (available from the American Presidency Project of the University of California, Santa Barbara).

- ↑ Phillip G. Payne (2009). Dead Last: The Public Memory of Warren G. Harding's Scandalous Legacy. Ohio University Press. pp. 118–20.

- ↑ Anthony 1998, 412-413.

- ↑ Corrado, John (November 8, 2005). "Was Warren Harding inducted into the KKK while president?". The Straight Dope. Chicago: Creative Loafing Media, Inc. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ↑ McCullough 1992, 164.

- ↑ Steinberg, 1962. Salisbury was a war buddy and former business partner of Truman's. Salisbury believed that Truman attempted "to give Jim Pendergast control of [their] business." Truman alerted federal officials about Salisbury, leading to Salisbury's conviction for filing a false affidavit. Salisbury contradicts Hinde's statement that the meeting at the Hotel Baltimore was one-on-one, naming at least six individuals who were present. Salisbury states that at the meeting, Truman had to receive a special dispensation to join, because his grandfather Solomon had been a Jew; however, Solomon was not a Jew, and the rumor of Truman's Jewish ancestry was only spread later, by the Klan, once the political lines had been drawn so that Truman was the Klan's enemy.

- ↑ Wade, 1987, 196, gives essentially this version of the events, but implies that the meeting was a regular Klan meeting, rather than an individual meeting between Truman and a Klan organizer. An interview with Hinde at the Truman Library's web site (“Oral History Interview with Edgar G. Hinde” by James R. Fuchs, 15 March 1962, retrieved June 26, 2005) portrays it as a one-on-one meeting at the Hotel Baltimore with a Klan organizer named Jones. Truman's biography, written by his daughter (Truman, 1973), agrees with Hinde's version, but does not mention the $10 initiation fee; the same biography reproduces a telegram from O.L. Chrisman stating that reporters from the Hearst papers had questioned him about Truman's past with the Klan, and that he had seen Truman at a Klan meeting, but that "if he ever became a member of the Klan I did not know it."

- ↑ McCullough 1992.

- ↑ Truman 1973.

- ↑ Truman 1973; McCullough 1992, 170.

- ↑ Hamby 1995.

- ↑ McCullough notes this extensively in his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Truman. While Truman had been raised in a family with Southern and Confederate leanings, he still said that he believed "in the brotherhood of all men before the law" (McCullough, p. 247). His work on civil rights was politically damaging but extensive nonetheless.

Sources

- Anthony, Carl Sferrazza. Florence Harding, New York: W. Morrow & Co. 1998.

- Dean, John; Schlesinger, Arthur M. Warren Harding (The American President Series), Times Books, 2004.

- Ferrell, Robert H. The Strange Deaths of President Harding. University of Missouri Press, 1996.

- Hamby, Alonzo L. Man of the People: A Life of Harry S Truman, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- McCullough, David. Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

- Steinberg. Man From Missouri. New York: Van Rees Press, 1962.

- Truman, Margaret. Harry S Truman. New York: William Morrow and Co. (1973).

- Wade, Wyn Craig. The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. New York: Simon and Schuster (1987).