Prince Marko

| Marko Mrnjavčević | |

|---|---|

|

King of the Serbian Land (de jure) | |

|

King Marko on a fresco above the south entrance to the church of Marko's Monastery near Skopje. He was a ktetor of this monastery. | |

| Reign | 1371–1395 |

| Predecessor | Vukašin Mrnjavčević |

| Successor | None (title abolished) |

| Born | c. 1335 |

| Died |

17 May 1395 Rovine, Wallachia (now Romania) |

| House | Mrnjavčević |

| Father | Vukašin Mrnjavčević |

| Mother | Alena |

Marko Mrnjavčević (Serbian Cyrillic: Марко Мрњавчевић, pronounced [mâːrko mr̩̂ɲaːʋt͡ʃeʋit͡ɕ]; c. 1335 – 17 May 1395) was the de jure Serbian king from 1371 to 1395, while he was the de facto ruler of territory in western Macedonia centered on the town of Prilep. He is known as Prince Marko (Serbian Cyrillic: Краљевић Марко, Kraljević Marko, IPA: [krǎːʎeʋit͡ɕ mâːrko]) and King Marko (Bulgarian: Крали Марко; Macedonian: Kрaле Марко) in South Slavic oral tradition, in which he has become a major character during the period of Ottoman rule over the Balkans. Marko's father, King Vukašin, was co-ruler with Serbian Tsar Stefan Uroš V, whose reign was characterised by weakening central authority and the gradual disintegration of the Serbian Empire. Vukašin's holdings included lands in western Macedonia, Kosovo and Metohija. In 1370 or 1371, he crowned Marko "young king"; this title included the possibility that Marko would succeed the childless Uroš on the Serbian throne.

On 26 September 1371, Vukašin was killed and his forces defeated in the Battle of Maritsa. About two months later, Tsar Uroš died. This formally made Marko the king of the Serbian land; however, Serbian noblemen, who had become effectively independent from the central authority, did not even consider to recognise him as their supreme ruler. Sometime after 1371, he became an Ottoman vassal; by 1377, significant portions of the territory he inherited from Vukašin were seized by other noblemen. King Marko, in reality, came to be a regional lord who ruled over a relatively small territory in western Macedonia. He funded the construction of the Monastery of Saint Demetrius near Skopje (better known as Marko's Monastery), which was completed in 1376. Marko died on 17 May 1395, fighting for the Ottomans against the Wallachians in the Battle of Rovine.

Although a ruler of modest historical significance, Marko became a major character in South Slavic oral tradition. He is venerated as a national hero by the Serbs, Macedonians and Bulgarians, remembered in Balkan folklore as a fearless and powerful protector of the weak, who fought against injustice and confronted the Turks during the Ottoman occupation.

Life

Until 1371

Marko was born about 1335 as the first son of Vukašin Mrnjavčević and his wife Alena.[1] The patronymic "Mrnjavčević" derives from Mrnjava, described by 17th-century Ragusan historian Mavro Orbin as a minor nobleman from Zachlumia (in present-day Herzegovina and southern Dalmatia).[2] According to Orbin, Mrnjava's sons were born in Livno in western Bosnia,[2] where he may have moved after Zachlumia was annexed from Serbia by Bosnia in 1326.[3] The Mrnjavčević familyn.b.1 may have later supported Serbian Emperor (tsar) Stefan Dušan in his preparations to invade Bosnia as did other Zachlumian nobles, and, fearing punishment, emigrated to the Serbian Empire before the war started.[3][4] These preparations possibly began two years ahead of the invasion,[4] which took place in 1350. From that year comes the earliest written reference to Marko's father Vukašin, describing him as Dušan's appointed župan (district governor) of Prilep,[3][5] which was acquired by Serbia from Byzantium in 1334 with other parts of Macedonia.[6] In 1355, at about age 47, Stefan Dušan died suddenly of a stroke.[7]

Dušan was succeeded by his 19-year-old son Uroš, who apparently regarded Marko Mrnjavčević as a man of trust. The new Emperor appointed him the head of the embassy he sent to Ragusa (now Dubrovnik, Croatia) at the end of July 1361 to negotiate peace between the empire and the Ragusan Republic after hostilities earlier that year. Although peace was not reached, Marko successfully negotiated the release of Serbian merchants from Prizren who were detained by the Ragusans and was permitted to withdraw silver deposited in the city by his family. The account of that embassy in a Ragusan document contains the earliest-known, undisputed reference to Marko Mrnjavčević.[8] An inscription written in 1356 on a wall of a church in the Macedonian region of Tikveš, mentions a Nikola and a Marko as governors in that region, but the identity of this Marko is disputed.[9]

Dušan's death was followed by the stirring of separatist activity in the Serbian Empire. The south-western territories, including Epirus, Thessaly, and lands in southern Albania, seceded by 1357.[10] However, the core of the state (the western lands, including Zeta and Travunia with the upper Drina Valley; the central Serbian lands; and Macedonia), remained loyal to Emperor Uroš.[11] Nevertheless, local noblemen asserted more and more independence from Uroš' authority even in the part of the state that remained Serbian. Uroš was weak and unable to counteract these separatist tendencies, becoming an inferior power in his own domain.[12] Serbian lords also fought each other for territory and influence.[13]

Vukašin Mrnjavčević was a skilful politician, and gradually assumed the main role in the empire.[14] In August or September 1365 Uroš crowned him king, making him his co-ruler. By 1370 Marko's potential patrimony increased as Vukašin expanded his personal holdings from Prilep further into Macedonia, Kosovo and Metohija, acquiring Prizren, Pristina, Novo Brdo, Skopje and Ohrid.[3] In a charter he issued on 5 April 1370 Vukašin mentioned his wife (Queen Alena) and sons (Marko and Andrijaš), signing himself as "Lord of the Serb and Greek Lands, and of the Western Provinces" (господинь зємли срьбьскои и грькѡмь и западнимь странамь).[15] In late 1370 or early 1371 Vukašin crowned Marko "Young King",[16] a title given to heirs presumptive of Serbian kings to secure their position as successors to the throne. Since Uroš was childless Marko could thus become his successor, beginning a new—Vukašin's—dynasty of Serbian sovereigns,[3] and ending the two-century Nemanjić dynasty. Most Serbian lords were unhappy with the situation, which strengthened their desire for independence from the central authority.[16]

Vukašin sought a well-connected spouse for Marko. A princess from the Croatian House of Šubić of Dalmatia was sent by her father, Grgur, to the court of their relative Tvrtko I, the ban of Bosnia. She was supposed to be raised and married by Tvrtko's mother Jelena. Jelena was the daughter of George II Šubić, whose maternal grandfather was Serbian King Dragutin Nemanjić.[17] The ban and his mother approved of Vukašin's idea to join the Šubić princess and Marko, and the wedding was imminent.[18][19] However, in April 1370 Pope Urban V sent Tvrtko a letter forbidding him to give the Catholic lady in marriage to the "son of His Magnificence, the King of Serbia, a schismatic" (filio magnifici viri Regis Rascie scismatico).[19] The pope also notified King Louis I of Hungary, nominal overlord of the ban,[20] of the impending "offence to the Christian faith", and the marriage did not occur.[18] Marko subsequently married Jelena (daughter of Radoslav Hlapen, the lord of Veria and Edessa and the major Serbian nobleman in southern Macedonia).[21]

During the spring of 1371, Marko participated in the preparations for a campaign against Nikola Altomanović, the major lord in the west of the Empire.[22] The campaign was planned jointly by King Vukašin and Đurađ I Balšić, lord of Zeta (who was married to Olivera, the king's daughter). In July of that year Vukašin and Marko camped with their army outside Scutari, on Balšić's territory, ready to make an incursion towards Onogošt in Altomanović's land. The attack never took place, since the Ottomans threatened the land of Despot Jovan Uglješa (lord of Serres and Vukašin's younger brother, who ruled in eastern Macedonia) and the Mrnjavčević forces were quickly directed eastward.[22] Having sought allies in vain, the two brothers and their troops entered Ottoman-controlled territory. At the Battle of Maritsa on 26 September 1371, the Turks annihilated the Serbian army;[23] the bodies of Vukašin and Jovan Uglješa were never found. The battle site, near the village of Ormenio in present-day eastern Greece, has ever since been called as Sırp Sındığı ("Serbian rout") in Turkish. The Battle of Maritsa had far-reaching consequences for the region, since it opened the Balkans to the Turks.[24]

After 1371

When his father died, "young king" Marko became king and co-ruler with Emperor Uroš. The Nemanjić dynasty ended soon afterwards, when Uroš died on 2 (or 4) December 1371 and Marko became the formal sovereign of Serbia.[25] Serbian lords, however, did not recognise him,[25] and divisions within the state increased.[24] After the two brothers' deaths and the destruction of their armies, the Mrnjavčević family was left powerless.[25] Lords around Marko exploited the opportunity to seize significant parts of his patrimony. By 1372 Đurađ I Balšić took Prizren and Peć, and Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović took Pristina.[26] By 1377 Vuk Branković acquired Skopje, and Albanian magnate Andrea Gropa became virtually independent in Ohrid; however, he may have remained a vassal to Marko as he had been to Vukašin.[24] Gropa's son-in-law was Marko's relative, Ostoja Rajaković of the clan of Ugarčić from Travunia. He was one of Serbian noblemen from Zachlumia and Travunia (adjacent principalities in present-day Herzegovina) who received lands in the newly conquered parts of Macedonia during Emperor Dušan's reign.[27]

The only sizable town kept by Marko was Prilep, from which his father rose. King Marko became a petty prince ruling a relatively small territory in western Macedonia, bordered in the north by the Šar mountains and Skopje; in the east by the Vardar and the Crna Reka rivers, and in the west by Ohrid. The southern limits of his territory are uncertain.[21] Marko shared his rule with his younger brother, Andrijaš, who had his own land.[24] Their mother, Queen Alena, became a nun after Vukašin's death, taking the monastic name Jelisaveta, but was co-ruler with Andrijaš for some time after 1371. The youngest brother, Dmitar, lived on land controlled by Andrijaš. There was another brother, Ivaniš, about whom little is known.[28] When Marko became an Ottoman vassal is uncertain, but it was probably not immediately after the Battle of Maritsa.[29]

At some point Marko separated from Jelena and lived with Todora, the wife of a man named Grgur, and Jelena returned to her father in Veria. Marko later sought to reconcile with Jelena but he had to send Todora to his father-in-law. Since Marko's land was bordered on the south by Hlapen's, the reconciliation may have been political.[21] Scribe Dobre, a subject of Marko's, transcribed a liturgical book for the church in the village of Kaluđerec,n.b.2 and when he finished, he composed an inscription which begins as follows:[30]

|

Слава сьвршитєлю богѹ вь вѣкы, аминь, а҃мнь, а҃м. Пыса сє сиꙗ книга ѹ Порѣчи, ѹ сєлѣ зовомь Калѹгєрєць, вь дьны благовѣрнаго кралꙗ Марка, ѥгда ѿдадє Ѳодору Грьгѹровѹ жєнѹ Хлапєнѹ, а ѹзє жєнѹ свою прьвовѣнчанѹ Ѥлєнѹ, Хлапєновѹ дьщєрє. |

|

Marko's fortress was on a hill north of present-day Prilep; its partially preserved remains are known as Markovi Kuli ("Marko's towers"). Beneath the fortress is the village of Varoš, site of the medieval Prilep. The village contains the Monastery of Archangel Michael, renovated by Marko and Vukašin, whose portraits are on the walls of the monastery's church.[21] Marko was ktetor of the Church of Saint Sunday in Prizren, which was finished in 1371, shortly before the Battle of Maritsa. In the inscription above the church's entrance, he is called "young king".[31]

The Monastery of St. Demetrius, popularly known as Marko's Monastery, is in the village of Markova Sušica (near Skopje) and was built from c. 1345 to 1376 (or 1377). Kings Marko and Vukašin, its ktetors, are depicted over the south entrance of the monastery church.[1] Marko is an austere-looking man in purple clothes, wearing a crown decorated with pearls. With his left hand he holds a scroll, whose text begins: "I, in the Christ God the pious King Marko, built and inscribed this divine temple ..." In his right hand, he holds a horn symbolizing the horn of oil with which the Old Testament kings were anointed at their coronation (as described in 1 Samuel 16:13). Marko is said to be shown here as the king chosen by God to lead his people through the crisis following the Battle of Maritsa.[25]

Marko minted his own money, in common with his father and other Serbian nobles of the time.[32] His silver coins weighed 1.11 grams,[33] and were produced in three types. In two of them, the obverse contained a five-line text: ВЬХА/БАБЛГОВ/ѢРНИКР/АЛЬМА/РКО ("In the Christ God, the pious King Marko").[34] In the first type, the reverse depicted Christ seated on a throne; in the second, Christ was seated on a mandorla. In the third type, the reverse depicted Christ on a mandorla; the obverse contained the four-line text БЛГО/ВѢРНИ/КРАЛЬ/МАРКО ("Pious King Marko"),[34] which Marko also used in the church inscription. He omitted a territorial designation from his title, probably in tacit acknowledgement of his limited power.[21] Although his brother Andrijaš also minted his own coins, the money supply in the territory ruled by the Mrnjavčević brothers primarily consisted of coins struck by King Vukašin and Tsar Uroš.[35] About 150 of Marko's coins survive in numismatic collections.[34]

By 1379, Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović, the ruler of Moravian Serbia, emerged as the most-powerful Serbian nobleman.[29][36] Although he called himself Autokrator of all the Serbs (самодрьжць вьсѣмь Србьлѥмь), he was not strong enough to unite all Serbian lands under his authority. The Balšić and Mrnjavčević families, Konstantin Dragaš (maternally a Nemanjić), Vuk Branković and Radoslav Hlapen continued ruling their respective regions.[29] In addition to Marko, Tvrtko I was crowned King of the Serbs and of Bosnia in 1377 in the Mileševa monastery. Maternally related to the Nemanjić dynasty, Tvrtko had seized western portions of the former Serbian Empire in 1373.[37]

On 15 June 1389 Serbian forces led by Prince Lazar, Vuk Branković, and Tvrtko's nobleman Vlatko Vuković of Zachlumia, confronted the Ottoman army led by Sultan Murad I at the Battle of Kosovo, the best-known battle in medieval Serbian history.[38] With the bulk of both armies wiped out and Lazar and Murad killed, the outcome of the battle was inconclusive. In its aftermath the Serbs had insufficient manpower to defend their lands, while the Turks had many more troops in the east. Serbian principalities which were not already Ottoman vassals became such over the next few years.[38]

In 1394, a group of Ottoman vassals in the Balkans renounced their vassalage.[39] Although Marko was not among them, his younger brothers Andrijaš and Dmitar refused to remain under Turkish dominance. They emigrated to the Kingdom of Hungary, entering the service of King Sigismund. They travelled via Ragusa, where they withdrew two-thirds of their late father's store of 96.73 kilograms (213.3 lb) of silver, leaving the remaining third for Marko. Although Andrijaš and Dmitar were the first Serbian nobles to emigrate to Hungary, the Serbian northward migration would continue throughout the Ottoman occupation.[39]

In 1395 the Turks attacked Wallachia to punish its ruler, Mircea I, for his incursions into their territory.[40] Three Serbian vassals fought on the Ottoman side: King Marko, Lord Konstantin Dragaš, and Despot Stefan Lazarević (son and heir of Prince Lazar). The Battle of Rovine, on 17 May 1395, was won by the Wallachians; Marko and Dragaš were killed. After their deaths the Turks annexed their lands, combining them into an Ottoman province centred in Kyustendil.[40] Thirty-six years after the Battle of Rovine, Konstantin the Philosopher wrote the Biography of Despot Stefan Lazarević and recorded what Marko said to Dragaš on the eve of the battle: "I pray the Lord to help the Christians, no matter if I will be the first to die in this war."[41]

In folk poetry

Serbian epic poetry

Marko Mrnjavčević is the most popular hero of Serbian epic poetry,[42] in which he is called "Kraljević Marko" (with the word kraljević meaning "prince"[42] or "king's son"). This informal title was attached to King Vukašin's sons in contemporary sources as a surname (Marko Kraljević),n.b.3 and it was adopted by the Serbian oral tradition as part of Marko's name.[43]

Poems about Kraljević Marko do not follow a storyline; what binds them into a poetic cycle is the hero himself,[44] with his adventures illuminating his character and personality.[45] The epic Marko had a 300-year lifespan; 14th- to 16th-century heroes appearing as his companions[44] include Miloš Obilić, Relja Krilatica, Vuk the Fiery Dragon and Sibinjanin Janko and his nephew, Banović Sekula.[46] Very few historical facts about Marko can be found in the poems, but they reflect his connection with the disintegration of the Serbian Empire and his vassalage to the Ottomans.[44] They were composed by anonymous Serbian poets during the Ottoman occupation of their land. According to American Slavicist George Rapall Noyes, they "combine tragic pathos with almost ribald comedy in a fashion worthy of an Elizabethan playwright."[42]

Serbian epic poetry agrees that King Vukašin was Marko's father. His mother in the poems was Jevrosima, sister of voivode Momčilo, the lord of the Pirlitor Fortress (on Mount Durmitor in Old Herzegovina). Momčilo is described as a man of immense size and strength with magical attributes: a winged horse and a sabre with eyes. Vukašin murdered him with the help of the voivode's young wife, Vidosava, despite Jevrosima's self-sacrificing attempt to save her brother. Instead of marrying Vidosava (the original plan), Vukašin killed the treacherous woman. He took Jevrosima from Pirlitor to his capital city, Skadar, and married her according to the advice of the dying Momčilo. She bore him two sons, Marko and Andrijaš, and the poem recounting these events says that Marko took after his uncle Momčilo.[47] This epic character corresponds historically with Bulgarian brigand and mercenary Momchil, who was in the service of Serbian Tsar Dušan; he later became a despot and died in the 1345 Battle of Peritheorion.[48] According to another account, Marko and Andrijaš were mothered by a vila (Slavic mountain nymph) married by Vukašin after he caught her near a lake and removed her wings so she could not escape.[49]

As Marko matured, he became headstrong; Vukašin once said that he had no control over his son, who went wherever he wanted, drank and brawled. Marko grew up into a large, strong man, with a terrifying appearance, which was also somewhat comical. He wore a wolf-skin cap pulled low over his dark eyes, his black moustache was the size of a six-month-old lamb and his cloak was a shaggy wolf-pelt. A Damascus sabre swung at his waist, and a spear was slung across his back. Marko's pernach weighed 66 okas (85 kilograms (187 lb)) and hung on the left side of his saddle, balanced by a well-filled wineskin on the saddle's right side. His grip was strong enough to squeeze drops of water from a piece of dry cornel wood. Marko defeated a succession of champions against overwhelming odds.[44][45]

The hero's inseparable companion was his powerful, talking piebald horse Šarac; Marko always gave him an equal share of his wine.[45] The horse could leap three spear-lengths high and four spear-lengths forward, enabling Marko to capture the dangerous, elusive vila Ravijojla. She became his blood sister, promising to help him in dire straits. When Ravijojla helped him kill the monstrous, three-hearted Musa Kesedžija (who almost defeated him), Marko grieved because he had slain a better man than himself.[50][51]

Marko is portrayed as a protector of the weak and helpless, a fighter against Turkish bullies and injustice in general. He was an idealised keeper of patriarchal and natural norms: in a Turkish military camp, he beheaded the Turk who dishonourably killed his father. He abolished the marriage tax by killing the tyrant who imposed it on the people of Kosovo. He saved the sultan's daughter from an unwanted marriage after she entreated him, as her blood brother, to help her. He rescued three Serbian voivodes (his blood brothers) from a dungeon and helped animals in distress. Marko was a rescuer and benefactor of people, and a promoter of life; "Prince Marko is remembered like a fair day in the year".[44]

Characteristic of Marko was his reverence and love for his mother, Jevrosima; he often sought her advice, following it even when it contradicted his own desires. She lived with Marko at his mansion in Prilep, his lodestar guiding him away from evil and toward good on the path of moral improvement and Christian virtues.[52] Marko's honesty and moral courage are noteworthy in a poem in which he was the only person who knew the will of the late Tsar Dušan regarding his heir. Marko refused to lie in favour of the pretenders—his father and uncles. He said truthfully that Dušan appointed his son, Uroš, heir to the Serbian throne. This almost cost him his life, since Vukašin tried to kill him.[45]

Marko is represented as a loyal vassal of the Ottoman sultan, fighting to protect the potentate and his empire from outlaws. When summoned by the sultan, he participated in Turkish military campaigns.[44] Even in this relationship, however, Marko's personality and sense of dignity were apparent. He occasionally made the sultan uneasy,[45] and meetings between them usually ended like this:

|

Цар с' одмиче, а Марко примиче, |

Serbian epic poem "Prince Marko and Musa Kesedžija"

The poem's conclusion, sung to a gusle (verses 220–281; 5:12) | |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Marko's fealty was combined with the notion that the servant was greater than his lord, as Serbian poets turned the tables on their conquerors. This dual aspect of Marko may explain his heroic status; for the Serbs he was "the proud symbol expressive of the unbroken spirit that lived on in spite of disaster and defeat,"[45] according to translator of Serbian epic poems David Halyburton Low.

In battle, Marko used not only his strength and prowess but cunning and trickery. Despite his extraordinary qualities he was not depicted as a superhero or a god, but as a mortal man. There were opponents who surpassed him in courage and strength. He was occasionally capricious, short-tempered or cruel, but his predominant traits were honesty, loyalty and fundamental goodness.[45]

With his comic appearance and behaviour, and his remarks at his opponents' expense, Marko is the most humorous character in Serbian epic poetry.[44] When a Moor struck him with a mace, Marko said laughingly, "O valiant black Moor! Are you jesting or smiting in earnest?"[55] Jevrosima once advised her son to cease his bloody adventures and plough the fields instead. He obeyed in a grimly humorous way,[45] ploughing the sultan's highway instead of the fields. A group of Turkish Janissaries with three packs of gold shouted at him to stop ploughing the highway. He warned them to keep off the furrows, but quickly wearied of arguing:

|

Диже Марко рало и волове, |

|

Marko, age 300, rode the 160-year-old Šarac by the seashore towards Mount Urvina when a vila told him that he was going to die. Marko then leaned over a well and saw no reflection of his face on the water; hydromancy confirmed the vila's words. He killed Šarac so the Turks would not use him for menial labor, and gave his beloved companion an elaborate burial. Marko broke his sword and spear, throwing his mace far out to sea before lying down to die. His body was found seven days later by Abbot Vaso and his deacon, Isaija. Vaso took Marko to Mount Athos and buried him at the Hilandar Monastery in an unmarked grave.[58]

Epic poetry of Bulgaria and Macedonia

"Krali Marko" has been one of the most popular characters in Bulgarian folklore for centuries.[59] Bulgarian epic tales in general (and those about Marko in particular) seem to originate from the southwestern part of the Bulgarian region,[60] primarily in the present-day Republic of Macedonia. Therefore, the tales are also part of the ethnic heritage of present-day Macedonia.

According to local legend Marko's mother was Evrosiya (Евросия), sister of the Bulgarian voivoda Momchil (who ruled territory in the Rhodope Mountains). At Marko's birth three narecnitsi (fairy sorceresses) appeared, predicting that he would be a hero and replace his father (King Vukašin). When the king heard this, he threw his son into the river in a basket to get rid of him. A samodiva named Vila found Marko and brought him up, becoming his foster mother. Because Marko drank the samodiva's milk, he acquired supernatural powers and became a Bulgarian freedom fighter against the Turks. He has a winged horse named Sharkolia ("dappled") and a stepsister, the samodiva Gyura. Bulgarian legends incorporate fragments of pagan mythology and beliefs, although the Marko epic was created as late as the 14–18th centuries. Among Bulgarian epic songs, songs about Krali Marko are common and pivotal.[61][62] Bulgarian folklorists who collected stories about Marko included educator Trayko Kitanchev (in the Resen region of western Macedonia) and Marko Cepenkov of Prilep (throughout the region).[63]

In legend

South Slavic legends about Kraljević Marko or Krali Marko are primarily based on myths much older than the historical Marko Mrnjavčević. He differs in legend from the folk poems; in some areas he was imagined as a giant who walked stepping on hilltops, his head touching the clouds. He was said to have helped God shape the earth, and created the river gorge in Demir Kapija ("Iron Gate") with a stroke of his sabre. This drained the sea covering the regions of Bitola, Mariovo and Tikveš in Macedonia, making them habitable. After the earth was shaped, Marko arrogantly showed off his strength. God took it away by leaving a bag as heavy as the earth on a road; when Marko tried to lift it, he lost his strength and became an ordinary man.[64]

Legend also has it that Marko acquired his strength after he was suckled by a vila. King Vukašin threw him into a river because he did not resemble him, but the boy was saved by a cowherd (who adopted him, and a vila suckled him). In other accounts, Marko was a shepherd (or cowherd) who found a vila's children lost in a mountain and shaded them against the sun (or gave them water). As a reward the vila suckled him three times, and he could lift and throw a large boulder. An Istrian version has Marko making a shade for two snakes, instead of the children. In a Bulgarian version, each of the three draughts of milk he suckled from the vila's breast became a snake.[64]

Marko was associated with large, solitary boulders and indentations in rocks; the boulders were said to be thrown by him from a hill, and the indentations were his footprints (or the hoofprints of his horse).[64] He was also connected with geographic features such as hills, glens, cliffs, caves, rivers, brooks and groves, which he created or at which he did something memorable. They were often named after him, and there are many toponyms—from Istria in the west to Bulgaria in the east—derived from his name.[65] In Bulgarian and Macedonian stories, Marko had an equally strong sister who competed with him in throwing boulders.[64]

In some legends, Marko's wonder horse was a gift from a vila. A Serbian story says that he was looking for a horse who could bear him. To test a steed, he would grab him by the tail and sling him over his shoulder. Seeing a diseased piebald foal owned by some carters, Marko grabbed him by the tail but could not move him. He bought (and cured) the foal, naming him Šarac. He became an enormously powerful horse and Marko's inseparable companion.[66] Macedonian legend has it that Marko, following a vila's advice, captured a sick horse on a mountain and cured him. Crusted patches on the horse's skin grew white hairs, and he became a piebald.[64]

According to folk tradition Marko never died; he lives on in a cave, in a moss-covered den or in an unknown land.[64] A Serbian legend recounts that Marko once fought a battle in which so many men were killed that the soldiers (and their horses) swam in blood. He lifted his hands towards heaven and said, "Oh God, what am I going to do now?" God took pity on Marko, transporting him and Šarac to a cave (where Marko stuck his sabre into a rock and fell asleep). There is moss in the cave; Šarac eats it bit by bit, while the sabre slowly emerges from the rock. When it falls on the ground and Šarac finishes the moss, Marko will awaken and reenter the world.[66] Some allegedly saw him after descending into a deep pit, where he lived in a large house in front of which Šarac was seen. Others saw him in a faraway land, living in a cave. According to Macedonian tradition Marko drank "eagle's water", which made him immortal; he is with Elijah in heaven.[64]

In modern culture

During the 19th century, Marko was the subject of several dramatizations. In 1831 the Hungarian drama Prince Marko, possibly written by István Balog,[67] was performed in Budim and in 1838, the Hungarian drama Prince Marko – Great Serbian Hero by Celesztin Pergő was staged in Arad.[67] In 1848 Jovan Sterija Popović wrote the tragedy The Dream of Prince Marko, in which the legend of sleeping Marko is its central motif. Petar Preradović wrote the drama Kraljević Marko, which glorifies southern Slav strength. In 1863 Francesco Dall'Ongaro presented his Italian drama, The Resurrection of Prince Marko.[67]

Of all Serbian epic or historical figures, Marko is considered to have given the most inspiration to visual artists;[68] a monograph on the subject lists 87 authors.[69] His oldest known depictions are 14th-century frescoes from Marko's Monastery and Prilep.[70][71] An 18th-century drawing of Marko is found in the Čajniče Gospels, a medieval parchment manuscript belonging to a Serbian Orthodox church in Čajniče in eastern Bosnia. The drawing is simple, unique in depicting Marko as a saint[72] and reminiscent of stećci reliefs.[73] Vuk Karadžić wrote that during his late-18th-century childhood he saw a painting of Marko carrying an ox on his back.[66]

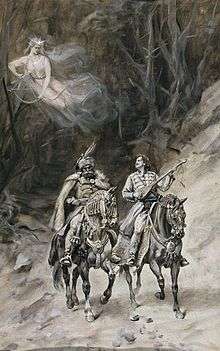

Nineteenth-century lithographs of Marko were made by Anastas Jovanović,[74] Ferdo Kikerec[73] and others. Artists who painted Marko during that century include Mina Karadžić,[74] Novak Radonić[75] and Đura Jakšić.[75] Twentieth-century artists include Nadežda Petrović,[76] Mirko Rački,[77] Uroš Predić[78] and Paja Jovanović.[78] A sculpture of Marko on Šarac by Ivan Meštrović was reproduced on a Yugoslavian banknote and stamp.[79] Modern illustrators with Marko as their subject include Alexander Key, Aleksandar Klas, Zuko Džumhur, Vasa Pomorišac and Bane Kerac.[69]

Motifs in multiple works are Marko and Ravijojla, Marko and his mother, Marko and Šarac, Marko shooting an arrow, Marko plowing the roads, the fight between Marko and Musa and Marko's death.[80] Also, several artists have tried to produce a realistic portrait of Marko based on his frescoes.[70] In 1924 Prilep Brewery introduced a light beer, Krali Marko.[81]

See also

Footnotes

^n.b.1 The family name "Mrnjavčević" was not mentioned in contemporary sources, nor was any other surname associated with this family. The oldest known source mentioning the name "Mrnjavčević" is Ruvarčev rodoslov "The Genealogy of Ruvarac", written between 1563 and 1584. It is unknown whether it was introduced into the Genealogy from some older source, or from the folk poetry and tradition.[82]

^n.b.2 This liturgical book, acquired in the 19th century by Russian collector Aleksey Khludov, is kept today in the State Historical Museum of Russia.

^n.b.3 The name Despotović ("despot's son") was applied in a similar way to Uglješa, the son of Despot Jovan Uglješa, King Vukašin's younger brother.[43]

Notes

- 1 2 Fostikov 2002, pp.49–50.

- 1 2 Orbin 1968, p.116.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fine 1994, pp.362–3.

- 1 2 Fine 1994, p.323.

- ↑ Stojanović 1902, p.37.

- ↑ Fine 1994, p.288.

- ↑ Fine 1994, p.335.

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1975, p.51. Ćorović 2001, "Распад Српске Царевине".

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1975, p.77.

- ↑ Šuica 2000, p.15.

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 358

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 345.

- ↑ Šuica 2000, p. 19

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1975, p.83.

- ↑ Miklošič 1858, p.180, № CLXVII.

- 1 2 Šuica 2000, p. 20

- ↑ Fajfrić (2000), "Први Котроманићи".

- 1 2 Jireček 1911, p.430.

- 1 2 Theiner 1860, p.97, № CXC.

- ↑ Theiner 1860, p.97, № CLXXXIX.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mihaljčić 1975, pp. 170–1

- 1 2 Mihaljčić 1975, p. 137; Fine 1994, p. 377

- ↑ Ćorović 2001, "Маричка погибија".

- 1 2 3 4 Fine 1994, pp. 379–82

- 1 2 3 4 Mihaljčić 1975, p.168.

- ↑ Šuica 2000, pp.35–6.

- ↑ Šuica 2000, p.42.

- ↑ Fostikov 2002, p.51.

- 1 2 3 Mihaljčić 1975, pp.164–5.

- ↑ Stojanović 1902, pp.58–9

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1975, p.166.

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1975, p.181.

- ↑ Šuica 2000, pp.133–6.

- 1 2 3 Mandić 2003, pp.24–5.

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1975, p.183.

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1975, p.220.

- ↑ Fine 1994, p.393.

- 1 2 Fine 1994, pp.408–11.

- 1 2 Fostikov 2002, pp.52–3.

- 1 2 Fine 1994, p.424.

- ↑ Konstantin 2000, "О погибији краља Марка и Константина Драгаша".

- 1 2 3 Noyes 1913, "Introduction".

- 1 2 Rudić 2001, p.89.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Deretić 2000, "Епска повесница српског народа".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Low 1922, "The Marko of the Ballads".

- ↑ Popović 1988, pp.24–8.

- ↑ Low 1922, "The Marriage of King Vukašin".

- ↑ Ćorović 2001, "Стварање српског царства".

- ↑ Bogišić 1878, pp. 231–2.

- ↑ Low 1922, "Marko Kraljević and the Vila"

- ↑ Low 1922, "Marko Kraljević and Musa Kesedžija"

- ↑ Popović 1988, pp.70–7.

- ↑ Karadžić 2000, "Марко Краљевић познаје очину сабљу".

- ↑ Low 1922, p.73.

- ↑ Karadžić 2000, "Марко Краљевић укида свадбарину".

- ↑ Karadžić 2000, "Орање Марка Краљевића".

- ↑ Low 1922, "Marko's Ploughing".

- ↑ Low 1922, "The Death of Marko Kraljević".

- ↑ For further information, read Veliko Iordanov (1901). Krali-Marko v bulgarskata narodna epika. Sofia: Sbornik na Bulgarskoto Knizhovno Druzhestvo.

- ↑ Mihail Arnaudov (1961). "Българско народно творчество в 12 тома. Том 1. Юнашки песни." (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on October 15, 2007.

- ↑ The River Danube in Balkan Slavic Folksongs, Ethnologia Balkanica (01/1997), Burkhart, Dagmar; Issue: 01/1997 , pp. 53–60

- ↑ A History of Macedonian Literature 865–1944, Volume 112 of Slavistic Printings and Reprintings, Charles A. Moser, Publisher Mouton, 1972.

- ↑ Прилеп; зап. Марко Цепенков (СбНУ 2, с. 116–120, № 2 – "Марко грабит Ангелина").

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Radenković 2001, pp.293–7.

- ↑ Popović 1988, pp.41–2.

- 1 2 3 Karadžić 1852, pp.345–6, s.v. "Марко Краљевић".

- 1 2 3 Šarenac 1996, p. 26

- ↑ Šarenac 1996, p. 06

- 1 2 Šarenac 1996, p. 02

- 1 2 Šarenac 1996, p. 05

- ↑ "Serbian Medieval Royal Attire". 2006-11-21. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ↑ Momirović 1956, p. 176

- 1 2 Šarenac 1996, p. 27

- 1 2 Šarenac 1996, p. 44

- 1 2 Šarenac 1996, p. 45

- ↑ Šarenac 1996, p. 28

- ↑ Šarenac 1996, p. 24

- 1 2 Šarenac 1996, p. 46

- ↑ Šarenac 1996, p. 33

- ↑ Šarenac 1996, p. 6–14

- ↑ "Krali Marko". Prilep Brewery. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- ↑ Rudić 2001, p.96.

References

- Bogišić, Valtazar (1878). Народне пјесме: из старијих, највише приморских записа [Folk poems: from older records, mostly from the Littoral] (in Serbian). 1. The Internet Archive.

- Ćorović, Vladimir (November 2001). Историја српског народа [History of the Serbian People] (in Serbian). Project Rastko.

- Deretić, Jovan (2000). Кратка историја српске књижевности [Short history of Serbian literature] (in Serbian). Project Rastko.

- Fajfrić, Željko (7 December 2000). Котроманићи (in Serbian). Project Rastko.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5.

- Fostikov, Aleksandra (2002). "О Дмитру Краљевићу [About Dmitar Kraljević]" (in Serbian). Историјски часопис [Historical Review] (Belgrade: Istorijski institut) 49. ISSN 0350-0802.

- Jireček, Konstantin Josef (1911). Geschichte der Serben [History of the Serbs] (in German). 1. The Internet Archive.

- Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović (1852). Српски рјечник [Serbian dictionary]. Vienna: Vuk Stefanović Karadžić.

- Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović (11 October 2000). Српске народне пјесме [Serbian folk poems] (in Serbian). 2. Project Rastko.

- Konstantin the Philosopher (2000). Gordana Jovanović ed. Житије деспота Стефана Лазаревића [Biography of Despot Stefan Lazarević] (in Serbian). Project Rastko.

- Low, David Halyburton (1922). The Ballads of Marko Kraljević. The Internet Archive.

- Mandić, Ranko (2003). "Kraljevići Marko i Andreaš" (in Serbian). Dinar: Numizmatički časopis (Belgrade: Serbian Numismatic Society) № 21. ISSN 1450-5185.

- Mihaljčić, Rade (1975). Крај Српског царства [The end of the Serbian Empire] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga.

- Miklošič, Franc (1858). Monumenta serbica spectantia historiam Serbiae Bosnae Ragusii (in Serbian and Latin). The Internet Archive.

- Momirović, Petar (1956). "Stari rukopisi i štampane knjige u Čajniču [Old manuscripts and printed books in Čajniče]" (in Serbian). Naše starine (Sarajevo: Zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture) 3.

- Noyes, George Rapall; Bacon, Leonard (1913). Heroic Ballads of Servia. The Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- Orbin, Mavro (1968). Franjo Barišić, Radovan Samardžić, Sima M. Ćirković eds. Краљевство Словена [The Realm of the Slavs] (in Serbian). trans. Zdravko Šundrica. Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga.

- Popović, Tatyana (1988). Prince Marko: The Hero of South Slavic Epics. New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2444-1.

- Radenković, Ljubinko (2001). "Краљевић Марко" (in Serbian). Svetlana Mikhaylovna Tolstaya, Ljubinko Radenković eds. Словенска митологија: Енциклопедијски речник [Slavic mythology: Encyclopedic dictionary]. Belgrade: Zepter Book World. ISBN 86-7494-025-0.

- Rudić, Srđan (2001). "O првом помену презимена Mрњавчевић [On the first mention of the Mrnjavčević surname]" (in Serbian). Историјски часопис [Historical Review] (Belgrade: Istorijski institut) 48. ISSN 0350-0802.

- Stojanović, Ljubomir (1902). Стари српски записи и натписи [Old Serbian inscriptions and superscriptions] (in Serbian). 1. Belgrade: Serbian Royal Academy.

- Šarenac, Darko (1996). "Марко Краљевић у машти ликовних уметника (in Serbian). Belgrade, BIPIF. ISBN 978-86-82175-03-2

- Šuica, Marko. (2000). Немирно доба српског средњег века: властела српских обласних господара [The turbulent era of the Serbian Middle Ages: the noblemen of the Serbian regional lords] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Službeni list SRJ. ISBN 86-355-0452-6.

- Theiner, Augustin (1860). Vetera monumenta historica Hungariam sacram illustrantia (in Latin). 2. The Internet Archive.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prince Marko. |

| Wikisource has several original texts related to: Prince Marko |

- The Ballads of Marko Kraljević, translated by David Halyburton Low (1922)

- Heroic Ballads of Servia, translated by George Rapall Noyes and Leonard Bacon (1913)

- Macedonian songs, fairy tales and legends about Marko (Macedonian)

- Bulgarian ballads (also here, with more information) and legends about Marko (Bulgarian)

- Marko, The King's Son: Hero of The Serbs by Clarence A. Manning (1932)

- Poem, "Marko Kraljević and the Vila"

- Conclusion of "Prince Marko and Musa Kesedžija" (verses 220–281)

- Web comic strip

Videos of Serbian epic poems sung to the accompaniment of the gusle:

- Prince Marko Recognises His Father's Sword

- Prince Marko Abolishes the Marriage Tax

- Prince Marko and the Eagle