Kirtanananda Swami

| Kirtanananda Swami | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

September 6, 1937 Peekskill, New York, USA |

| Died |

October 24, 2011 (aged 74) Thane, India |

| Religion | Hinduism |

Kirtanananda Swami, also known as Swami Bhaktipada[1] (September 6, 1937 – October 24, 2011)[2] was the highly controversial charismatic Hare Krishna guru and co-founder of the New Vrindaban Hare Krishna community in Marshall County, West Virginia, where he served as spiritual leader for 26 years (from 1968 until 1994).

Early life

Kirtanananda was born Keith Gordon Ham in Peekskill, New York, in 1937, the son of a Conservative Baptist minister. Keith Ham inherited his father's missionary spirit and attempted to convert classmates to his family's faith. Despite an acute case of poliomyelitis which he contracted around his 17th birthday, he graduated with honors from high school in 1955. He received a Bachelor of Arts in History from Maryville College in Maryville, Tennessee on May 20, 1959, and graduated magna cum laude, first in his class of 117.

He received a Woodrow Wilson fellowship to study American history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he remained for three years. There he met Howard Morton Wheeler (1940–1989), an undergraduate English major from Mobile, Alabama who became his lover and lifelong friend. Later Kirtanananda acknowledged that, before becoming a Hare Krishna, he had had a homosexual relationship with Wheeler for many years, which was documented in the film Holy Cow Swami, a 1996 documentary by Jacob Young.[3]

The two resigned from the university on February 3, 1961, and left Chapel Hill after being threatened with an investigation over a "sex scandal", and moved to New York City. Ham promoted LSD use and became an LSD guru. He worked as an unemployment claims reviewer. He enrolled at Columbia University in 1961, where he received a Waddell fellowship to study religious history with Whitney Cross, but he quit academic life after several years when he and Wheeler travelled to India in October 1965 in search of a guru. Unsuccessful, they returned to New York after six months.[4]

As Kirtanananda

In June 1966, after returning from India, Ham met the Bengali Gaudiya Vaishnava guru A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (then known simply as "Swamiji" to his disciples), the founder-acharya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), more popularly known in the West as the Hare Krishnas. After attending Bhagavad-gita classes at the modest storefront temple at 26 Second Avenue in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, Ham accepted Swamiji as his spiritual master, receiving initiation as "Kirtanananda Dasa" ("the servant of one who takes pleasure in kirtan") on September 23, 1966. Swamiji sometimes called him "Kitchen-ananda" because of his cooking expertise. Howard Wheeler was initiated two weeks earlier on September 9, 1966 and received the name "Hayagriva Dasa".[5]

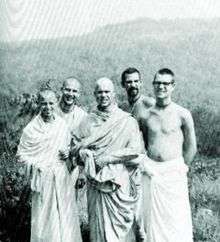

Kirtanananda was among the first of Swamiji's western disciples to shave his head (apart from the sikha), don robes (traditional Bengali Vaishnava clothing consists of dhoti and kurta), and move into the temple. In March 1967, on the order of Swamiji, Kirtanananda and Janus Dambergs (Janardana Dasa), a French-speaking university student, established the Montreal Hare Krishna temple. On August 28, 1967, while travelling with Swamiji in India, Kirtanananda Dasa became Prabhupada's first disciple to be initiated into the Vaishnava order of renunciation (sannyasa: a lifelong vow of celibacy in mind, word and body), and received the name Kirtanananda Swami. Within weeks, however, he returned to New York City against Prabhupada's wishes and attempted to add esoteric cultural elements of Christianity to Prabhupada's devotional bhakti system. Other disciples of Prabhupada saw this as a takeover attempt. In letters from India, Prabhupada soundly chastised him and banned him from preaching in ISKCON temples.[6]

The New Vrindaban community

Kirtanananda moved in with Wheeler, by then known as Hayagriva Dasa, who was teaching English at a community college in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania. In the San Francisco Oracle (an underground newspaper), Kirtanananda saw a letter from Richard Rose, Jr., who wanted to form an ashram on his land in Marshall County, West Virginia. "The conception is one of a non-profit, non-interfering, non-denominational retreat or refuge, where philosophers might come to work communally together, or independently, where a library and other facilities might be developed."[7]

On a weekend free of classes (March 30–31, 1968), Kirtanananda and Hayagriva visited the two properties owned by Rose. After Hayagriva returned to Wilkes Barre, Kirtanananda stayed on in Rose's backwoods farmhouse. In July 1968, after a few months of Kirtanananda's living in isolation, he and Hayagriva visited Prabhupada in Montreal. Prabhupada "forgave his renegade disciples in Montreal with a garland of roses and a shower of tears".[8] When the pair returned to West Virginia, Richard Rose, Jr. and his wife Phyllis gave Hayagriva a 99-year lease on the 132.77-acre property for $4,000, with an option to purchase for $10 when the lease expired. Hayagriva put down a $1,500 deposit.[9]

Prabhupada established the purpose and guided the development of the community in dozens of letters and four personal visits (1969, 1972, 1974 and 1976). New Vrindaban would fulfill four major functions for ISKCON:

- establish and promote the simple, agrarian Krishna conscious lifestyle, including cow protection,

- establish a place of pilgrimage in the West by building seven temples on seven hills,

- train up a class of brahmin teachers by training boys at the gurukula (school of the guru), and

- establish a society based on varnashram-dharma.

Kirtanananda eventually established himself as leader and sole authority over the community. In New Vrindaban publications he was honored as "Founder-Acharya" of New Vrindaban, in imitation of Prabhupada's title of Founder-Acharya of ISKCON. Over time the community expanded, devotees from other ISKCON centers moved in, and cows and land were acquired until New Vrindaban properties consisted of nearly 5,000 acres. New Vrindaban became a favorite ISKCON place of pilgrimage and many ISKCON devotees attended the annual Krishna Janmashtami festivals. For some, Kirtanananda's previous offenses were forgiven. Many devotees admired him for his austere lifestyle (for a time he lived in an abandoned chicken coop), his preaching skills[10] and devotion to the presiding deities of New Vrindaban: Sri Sri Radha Vrindaban Chandra.[11] For other devotees who had challenged him and thereby encountered his wrath, he was a source of fear.

Palace of Gold

Late in 1972 Kirtanananda and sculptor-architect Bhagavatananda Dasa decided to build a home for Prabhupada. In time, the plans for the house developed into an ornate memorial shrine of marble, gold and carved teakwood, dedicated posthumously during Labor Day weekend, on Sunday, September 2, 1979. The completion of the Palace of Gold catapulted New Vrindaban into mainstream respectability as tens (and eventually hundreds) of thousands of tourists began visiting the Palace each year. A "Land of Krishna" theme park and a granite "Temple of Understanding" in classical South Indian style were designed to make New Vrindaban a "Spiritual Disneyland". The ground-breaking ceremony of the proposed temple on May 31, 1985, was attended by dozens of dignitaries, including a United States congressman from West Virginia. One publication called it "the most significant and memorable day in the history of New Vrindaban."[12]

Upon Prabhupada's death on November 14, 1977, Kirtanananda and ten other high-ranking ISKCON leaders assumed the position of initiating gurus to succeed him. In March 1979, he accepted the honorific title "Bhaktipada."

"Interfaith era"

In 1986 Kirtanananda began his so-called interfaith experiment and the community became known as the "New Vrindaban City of God". He attempted to "de-Indianize" Krishna Consciousness to help make it more accessible to westerners, just as he had done previously in 1967. Devotees wore Franciscan-style robes instead of dhotis and saris; they chanted in English with western instruments such as the pipe organ and accordions[13] instead of chanting in Sanskrit and Bengali with mridanga drums and cymbals; male devotees grew hair and beards instead of shaving their heads and faces; female devotees were awarded the sannyasini order and encouraged to preach independently; japa was practiced silently; and an interfaith community was attempted.

Assault and ensuing expulsion from ISKCON

On October 27, 1985, during a New Vrindaban bricklaying marathon, a crazed and distraught devotee bludgeoned Kirtanananda on the head with a heavy steel tamping tool.[14] Kirtanananda was critically injured and remained in a coma for ten days. Gradually he recovered most of his faculties, although devotees who knew him well said that his personality had changed.

Some close associates began leaving the community. On March 16, 1987, during their annual meeting at Mayapur, India, the ISKCON Governing Body Commission expelled Kirtanananda from the society for various deviations.[15] They claimed he had defied ISKCON policies and had claimed to be the sole spiritual heir to Prabhupada's movement. Thirteen members voted for the resolution, two abstained, and one member, Bhakti Tirtha Swami, voted against the resolution.[16]

Kirtanananda then established his own organization, The Eternal Order of the League of Devotees Worldwide, taking several properties with him. By 1988, New Vrindaban had 13 satellite centers in the United States and Canada, including New Vrindaban. New Vrindaban was excommunicated from ISKCON the same year.[17]

Criminal conviction and imprisonment

In 1990 the US federal government indicted Kirtanananda on five counts of racketeering, six counts of mail fraud, and conspiracy to murder two of his opponents in the Hare Krishna movement (Stephen Bryant and Charles St. Denis).[18] The government claimed that he had illegally amassed a profit of more than $10.5 million over four years. It also charged that he ordered the killings because the victims had threatened to reveal his sexual abuse of minors.[18]

On March 29, 1991, Kirtanananda was convicted on nine of the 11 charges (the jury failed to reach a verdict on the murder charges), but the Court of Appeals, convinced by the expert arguments of defense attorney Alan Morton Dershowitz (a criminal law professor at Harvard University who represented such celebrated and wealthy clients as Claus von Bülow, Mike Tyson and O. J. Simpson), threw out the convictions, saying that child molestation evidence had unfairly prejudiced the jury against Kirtanananda, who was not charged with those crimes.[18] On August 16, 1993, he was released from house arrest in a rented apartment in the Warwood neighborhood of Wheeling, where he had lived for nearly two years, and returned triumphantly to New Vrindaban.[18]

Kirtanananda lost his iron grip on the community after the September 1993 "Winnebago Incident" during which he was accidentally discovered in a compromising position with a young male Malaysian disciple in the back of a Winnebago van,[18] and the community split into two camps: those who still supported Kirtanananda and those who challenged his leadership. During this time he retired to his rural retreat at "Silent Mountain" near Littleton, West Virginia.[18]

The challengers eventually ousted Kirtanananda and his supporters completely, and ended the "interfaith era" in July 1994 by returning the temple worship services to the standard Indian style advocated by Swami Prabhupada and practiced throughout ISKCON. Most of Kirtanananda's followers left New Vrindaban and moved to the Radha Muralidhar Temple in New York City, which remained under Kirtanananda's control. New Vrindaban returned to ISKCON in 1998.[17]

In 1996, before Kirtanananda's retrial was completed, he pleaded guilty to one count of racketeering (mail fraud).[18] He was sentenced to 20 years in prison but was released on June 16, 2004.[19]

On September 10, 2000, the ISKCON Child Protection Office concluded a 17-month investigation and determined that Kirtanananda had molested two boys. He was prohibited from visiting any ISKCON properties for five years and offered conditions for reinstatement within ISKCON:[20]

- He must contribute at least $10,000 to an organization dedicated to serving Vaishnava youth, such as Children of Krishna, the Association for the Protection of Vaishnava Children, or a gurukula approved by the APVC.

- He must write apology letters to all the victims described in this letter. In these letters he must fully acknowledge his transgressions of child abuse, and he must take full responsibility for those actions. Also, he must express appropriate remorse, and offer to make amends to the victims. These letters should be sent to the APVC, not directly to the victims.

- He must undergo a psychological evaluation by a mental health professional pre-approved by the APVC, and he must comply with recommendations for ongoing therapy described in the evaluation report and by the APVC.

- He must fully comply with all governmental investigations into misconduct on his part.

Kirtanananda never satisfied any of these conditions.[21]

After imprisonment

For four years after his release from prison, Kirtanananda (now confined to a wheelchair) resided at the Radha Murlidhara Temple at 25 First Avenue in New York City, which was purchased in 1990[22] for $500,000 and maintained by a small number of disciples and followers, although the temple board later attempted to evict him.[23]

On March 7, 2008, Kirtanananda left the United States for India, where he expected to remain for the rest of his life. "There is no sense in staying where I’m not wanted," he explained, referring to the desertions through the years by most of his American disciples and to the attempts to evict him from the building. At the time of his death Kirtanananda still had a significant number of loyal disciples in India and Pakistan, who worshiped him as "guru" and published his last books. He continued preaching a message of interfaith: that the God of the Christians, Jews, Muslims, and Vaishnavas is the same; and that men of faith from each religion should recognize and appreciate the faith of men of other paths. "Fundamentalism is one of the most dangerous belief-systems in the world today. Fundamentalism doesn’t promote unity; it causes separatism. It creates enmity between people of faith. Look at the Muslims; Mohammed never intended that his followers should spread their religion by the sword. It is more important today than at any other time to preach about the unity of all religions."[24]

Death

Kirtanananda died on October 24, 2011 at a hospital in Thane, near Mumbai, India, aged 74. His brother, Gerald Ham, reported the cause of death to be kidney failure.[2]

Bibliography

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

|

Sampradayas |

|

Philosophers–acharyas |

|

Related traditions |

|

|

Kirtanananda Swami authored two dozen published books, some of which were translated and published in Gujarati, German, French and Spanish editions. Some books attributed to him and published in his name were actually written by volunteer ghostwriters.[25]

Books by Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada:

- The Song of God: A Summary Study of Bhagavad-gita As It Is (1984)

- Christ and Krishna: The Path of Pure Devotion (1985)

- L'amour de Dieu: Le Christianisme et La Tradition Bhakti (1985) French edition

- Eternal Love: Conversations with the Lord in the Heart (1986), based on Thomas à Kempis’ Imitation of Christ

- The Song of God: A Summary Study of Bhagavad-gita As It Is (c. 1986) Gujarati edition

- On His Order (1987)

- The Illustrated Ramayana (1987)

- Lila in the Land of Illusion (1987), based on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland

- Bhaktipada Bullets (1988), compiled by Devamrita Swami

- A Devotee’s Journey to the City of God (1988), based on John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress

- Joy of No Sex (1988)

- Excerpts from The Bhaktipada Psalms (1988)

- Le pur amour de Dieu: Christ & Krishna (1988), French edition

- One God: The Essence of All Religions (1989), Indian publication

- Heart of the Gita: Always Think of Me (1990)

- How To Say No To Drugs (1990)

- Spiritual Warfare: How to Gain Victory in the Struggle for Spiritual Perfection (1990), a sequel to Eternal Love

- How to Love God (1992), based on Saint Francis de Sales’ Treatise on the Love of God

- Sense Grataholics Anonymous: A Twelve Step Meeting Suggested Sharing Format (c. 1995)

- On Becoming Servant of The Servant (undated), Indian publication

- Divine Conversation (2004), Indian publication

- The Answer to Every Problem: Krishna Consciousness (2004), Indian publication

- A Devotee's Handbook for Pure Devotion (2004), Indian publication [26]

- Humbler than a Blade of Grass (2008), Indian publication

Articles and poems by, and interviews with Kirtanananda Swami published in Back to Godhead magazine:

- 1966, Vol 01, No 01, (untitled poem, no. 1)

- 1966, Vol 01, No 01, (untitled poem, no. 2)

- 1966, Vol 01, No 01, (untitled poem, no. 3)

- 1966, Vol 01, No 02, (untitled poem, no. 4)

- 1969, Vol 01, No 29, "Man’s Link to God"

- 1969, Vol 01, No 31, "Krishna’s Light vs. Maya’s Night"

- 1970, Vol 01, No 32, "Prasadam: Food for the Body, Food for the Soul and Food for God"

- 1970, Vol 01, No 33, "Observing the Armies on the Battlefield of Kuruksetra, Part 1"

- 1970, Vol 01, No 34, "Contents of the Gita Summarized"

- 1970, Vol 01, No 35, "Karma-yoga—Perfection through Action, Part 3: Sankirtana"

- 1970, Vol 01, No 37, "Transcendental Knowledge, Part 4: He Is Transcendental"

- 1970, Vol 01, No 38, "Karma-yoga—Action in Krishna Consciousness, Part 5: Work in Devotion"

- 1970-1973, Vol 01, No 40, "Sankhya-yoga: Absorption in the Supreme"

- 1970-1973, Vol 01, No 41, "Knowledge of the Absolute: It Is Not a Cheap Thing"

- 1970-1973, Vol 01, No 42, "Attaining the Supreme: What Is Brahman?"

- 1974, Vol 01, No 66, "Turning Our Love Toward Krishna"

- 1977, Vol 12, No 12, "The Things Christ Had to Keep Secret"

- 1986, Vol 21, No 07, "The Heart’s Desire: How can we find happiness that is not purchased with our pain?"

References

- ↑ Within ISKCON he is now known as "Kirtanananda das", as he is regarded as long-fallen from his sannyasa vows of celibacy.

- 1 2 Margalit Fox (October 24, 2011). "Swami Bhaktipada, Ex-Hare Krishna Leader, Dies at 74". The New York Times.

- ↑ A clip of Kirtanananda with the court transcript in which he was asked, "Back in the 1950s and early 60s, were you homosexual?", and his response ("Yes.") can be seen here. on YouTube

- ↑ Hayagriva Das, The Hare Krishna Explosion (Palace Press, New Vrindaban WV: 1985)

- ↑ Satsvarupa dasa Goswami, Srila Prabhupada-lilamrta, Vol. 2 (Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, Los Angeles, CA: 1980)

- ↑ Letters From Srila Prabhupada, Vol. 1 (The Vaisnava Institute in association with the BBT, Culver City, CA: 1987)

- ↑ Richard Rose, The San Francisco Oracle (December 1967)

- ↑ Hayagriva Das, "Chant", Brijabasi Spirit (November 1981), p. 20.

- ↑ Lease available for viewing at Marshall County Courthouse, Moundsville, West Virginia

- ↑ Back to Godhead magazine published three of his poems and 14 articles between 1966 and 1986

- ↑ Kuladri Das, "Vyasa-puja Homage" (Shri Vyasa-puja: September 4, 1978), p. 6.

- ↑ "Government Officials Attend Ceremony," Land of Krishna, vol. 1, no. 5 (July 1985).

- ↑ See image of "City of God Accordion Ensemble" at File:Newvrindabanaccordions.jpg

- ↑ This was Triyogi dasa, who had come to New Vrindaban in September 1985 to attend the much-publicized "Prabhupada Disciple Meetings." After the conference concluded, he decided to stay at New Vrindaban for a time. His services at New Vrindaban were menial; he assisted in the kitchen and picked up litter around the Palace. He appeared to have some prominent personality dysfunctions, he was sometimes observed muttering under his breath to himself, and the New Vrindaban residents who knew him considered him mentally unstable. Triyogi had asked Kirtanananda to initiate him into the order of sannyas. Kirtanananda said that he must first "prove himself" as a preacher: "I told him I didn't feel I could do it. I didn't know him well enough. I told him to stay here at New Vrindaban for six months to a year first, and he became disturbed about that". (Kirtanananda Swami, quoted by Eric Harrison in "Violence is Focus of Krishna Inquiry", The Philadelphia Inquirer (August 21, 1986), 16-A.) Triyogi was visibly upset and confided in another New Vrindaban devotee that "he felt he had to either kill himself, kill Bhaktipada, or leave". Later he told that same devotee that he would not kill anyone; he would simply leave. (Tulsi das quoting Triyogi, cited by Terry Smith in "Krishnas May Investigate New Disciples", The Wheeling Intelligencer (October 31, 1985), pp. 1, 6.)

- ↑ See http://www.dandavats.com/wp-content/uploads/GBCresolutions/GBCRES87.htm

- ↑ The Perils of Succession: Heresies of Authority and Continuity In the Hare Krishna Movement, Tamal Krishna Goswami

- 1 2 Lewis, James (2011). Violence and New Religious Movements. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 281.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Holy Cow Swami, a documentary movie by Jacob Young (WVEBA, 1996)

- ↑ Federal Bureau of Prisons record of release

- ↑ Official Decision on the Case of Kirtanananda Das, ISKCON Central Office of Child Protection (September 10, 2000)

- ↑ The four conditions for reinstatement into ISKCON formulated by the ISKCON Child Protection Office were in response to particular crimes against two boys. However, these conditions do not take into account the March 1987 GBC resolution which excommunicated Kirtanananda from ISKCON for other offenses. Therefore, even if the conditions imposed by the Child Protection Office were satisfied in full, Kirtanananda would still be unwelcome in ISKCON.

- ↑ The installation of Sri Sri Radha Murlidhara was reported in The City of God Examiner (issue no. 48, January 2, 1991)

- ↑ "Hare Krishnas clash as eviction effort divides First Ave. building" by Tien-Shun Lee. The Villager (New York: July 18, 2007)

- ↑ Kirtanananda Swami, cited by Henry Doktorski in "Kirtanananda Swami Leaves US, Moves To India Permanently" (Brijabasi Spirit, March 7, 2008)

- ↑ Sri Galim wrote The Illustrated Ramayana (1987), Rukmini devi dasi wrote Joy of No Sex (1988), and "True Peace" wrote Heart of the Gita: Always Think of Me (1990).

- ↑ See http://www.kirtananandaswami.org/HandbookforPureDevotion.pdf

External links

- Website of Kirtanananda

- Website of New Vrindaban Community

- Website of Palace of Gold

- New Vrindaban: The Black Sheep of ISKCON