Kingdom of Hungary (1920–46)

| Kingdom of Hungary | ||||||

| Magyar Királyság | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| Motto "Regnum Mariae Patrona Hungariae"[1] (Latin) "Kingdom of Mary, the Patron of Hungary" | ||||||

| Anthem Himnusz Hymn | ||||||

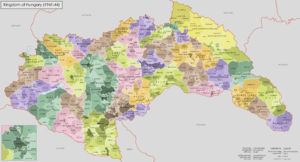

.svg.png) Extent of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1942. | ||||||

| Capital | Budapest | |||||

| Languages | Hungarian (official) · German · Romanian · Rusyn · Slovak · Croatian · Serbian · Slovene · Carpathian Romani · Mideastern Yiddish | |||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism · Calvinism · Lutheranism · Eastern Orthodoxy · Eastern Catholicism · Unitarianism · Judaism | |||||

| Government | Authoritarian regency (1920–1944) Agrarian fascist one-party state (1944–1945) | |||||

| King | ||||||

| • | 1920–1946 | Vacant a | ||||

| Head of State | ||||||

| • | 1920–1944 | Miklós Horthyb | ||||

| • | 1944–1945 | Ferenc Szálasic | ||||

| • | 1945–1946 | High National Councild | ||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||

| • | 1920 (first) | Károly Huszár | ||||

| • | 1945–1946 (last) | Zoltán Tildy | ||||

| Legislature | Diet | |||||

| • | Upper | Felsőház | ||||

| • | Representatives | Képviselőház | ||||

| Historical era | Interwar · World War II | |||||

| • | Monarchy restored | 29 February[2] 1920 | ||||

| • | Treaty of Trianon | 4 June 1920 | ||||

| • | First Vienna Award | 2 November 1938 | ||||

| • | Second Vienna Award | 30 August 1940 | ||||

| • | Hungarist take-over | 16 October 1944 | ||||

| • | Monarchy abolished | 1 February 1946 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | 1920[3] | 92,833 km² (35,843 sq mi) | ||||

| • | 1930[4] | 93,073 km² (35,936 sq mi) | ||||

| • | 1941[5] | 172,149 km² (66,467 sq mi) | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 1920[6] est. | 7,980,143 | ||||

| Density | 86 /km² (222.6 /sq mi) | |||||

| • | 1930[7] est. | 8,688,319 | ||||

| Density | 93.3 /km² (241.8 /sq mi) | |||||

| • | 1941[8] est. | 14,669,100 | ||||

| Density | 85.2 /km² (220.7 /sq mi) | |||||

| Currency | Hungarian korona (1920–1927) Hungarian pengő (1927–1946) | |||||

| Today part of | | |||||

| a. | Claimed by former King Charles IV of Hungary in 1921. | |||||

| b. | Miklós Horthy used the title "Regent". | |||||

| c. | Ferenc Szálasi used the title "Nation Leader". | |||||

| d. | Ruled as a collective head of state. | |||||

The Kingdom of Hungary (Hungarian: Magyar Királyság), also known as the Regency, existed from 1920 to 1946 as a de factonote 1 country under Regent Miklós Horthy. Horthy officially represented the Hungarian monarchy of Charles IV, Apostolic King of Hungary. Attempts by Charles IV to return to the throne were prevented by threats of war from neighbouring countries and by the lack of support from Horthy (see the conflict of Charles IV with Miklós Horthy).

The country has been regarded by some historians to have been a client state of Germany from 1938 to 1944.[9] The Kingdom of Hungary under Horthy was an Axis Power during most of World War II. In 1944, after Horthy's government considered leaving the war, Hungary was occupied by Nazi Germany and Horthy was deposed. The Arrow Cross Party's leader Ferenc Szálasi established a new Nazi-backed government, effectively turning Hungary into a German puppet state.

After World War II, Hungary fell within the Soviet Union's sphere of interest. In 1946, the Second Hungarian Republic was established under Soviet influence. In 1949, the communist Hungarian People's Republic was founded.

Formation

Upon the dissolution and break-up of Austria-Hungary after World War I, the Hungarian Democratic Republic and then the Hungarian Soviet Republic were briefly proclaimed in 1918 and 1919, respectively. The short-lived communist government of Béla Kun launched what was known as the "Red Terror", involving Hungary in an ill-fated war with Romania. In 1920, the country fell into a period of civil conflict, with Hungarian anti-communists and monarchists violently purging the nation of communists, leftist intellectuals, and others whom they felt threatened by, especially Jews. This period was known as the "White Terror". In 1920, after the pullout of the last of the Romanian occupation forces, the Kingdom of Hungary was restored.

On February 29, 1920, a coalition of right-wing political forces united and returned Hungary to being a constitutional monarchy. However, it was obvious that the Allies would not accept any return of Charles IV. With civil unrest too great to choose a new king, it was decided to select a regent to represent the monarchy. Miklós Horthy, the last commanding admiral of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, was chosen for this position on 1 March. Sándor Simonyi-Semadam was the first Prime Minister of Horthy's regency.

Government

.svg.png)

Horthy's rule as Regent possessed characteristics such that it could be construed a dictatorship. As a counterpoint, his powers were a continuation of the constitutional powers of the King of Hungary, adopted earlier during the Hungary federation with the Austrian Empire.[10] As Regent, Horthy had the power to adjourn or dissolve the Hungarian Diet (parliament) at his own discretion; he appointed the Hungarian Prime Minister.[11]

The succession after Horthy's death or abdication was never officially established; presumably the Hungarian Parliament would have selected a new regent, or possibly attempted to restore the Habsburgs under Crown Prince Otto. In January 1942, Parliament appointed Horthy's eldest son István as Deputy Regent and expected successor. Whether this represents an attempt to gradually re-establish monarchy in Hungary is unclear; at any rate, István was killed in an airplane crash in August that year, and a new Deputy Regent was not appointed.

During his first ten years, Horthy led increased repression of Hungarian minorities. In 1920, the numerus clausus law formally placed limits on the number of minorities permitted to go to university and legalized corporal punishment. Although the law seemingly applied an equal measure to all minorities, the ethnicity quota system was never really introduced and the law should hide anti-Jewish action from abroad.[12] Limitations were relaxed in 1928. Racial criteria in admitting new students were removed and replaced by social criteria. Five categories were set up: civil servants, war veterans and army officers, small landowners and artisans, industrialists, and the merchant classes.[13][14] Under the leadership of Prime Minister István Bethlen the election system was changed, excluding Budapest and it's vicinity and cities with county municipial rights, the open vote system was reintroduced.[15] His political party, the Party of Unity, won repeated elections. Bethlen pushed for revision of the Treaty of Trianon. After the collapse of the Hungarian economy from 1929 to 1931, national turmoil pushed Bethlen to resign as Prime Minister. In 1938 the election system was restored.[15]

Social conditions in the kingdom did not improve as time passed, as extremely small percentages of the population controlling much of the country’s wealth. Jews were continually pressured to assimilate into Hungarian mainstream culture.

The desperate situation forced Regent Horthy to accept far-right politician Gyula Gömbös as Prime Minister. He pledged to retain the existing political system. Gömbös agreed to abandon his extreme anti-Semitism and allow some Jews into the government.

In power, Gömbös moved Hungary towards a one-party government like those of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Pressure by Nazi Germany for extreme anti-Semitism forced Gömbös out and Hungary pursued anti-Semitism under its “Jewish Laws”. Initially, the government passed laws restricting Jews to 20 percent in a number of professions. Later it scapegoated the Jews for the country’s failing economy.

In 1944, responding to the advancing Soviet forces, Regent Miklós Horthy deposed the pro-German Prime Minister and installed a more balanced government in an effort to deal with the Allies and avoid occupation by the Soviet Union. Shortly afterward, German forces invaded Hungary, deposed Horthy as Regent, and installed a puppet regime led by Ferenc Szálasi of the anti-Semitic and pro-Nazi Arrow Cross Party. The Arrow Cross Party never abolished the Monarchy as a form of government, as Hungarian newspapers kept referring to the country as the Kingdom of Hungary (Magyar Királyság), although Magyarország (Hungary) was used as an alternative.[16][17] From May to June 1944, Hungarian authorities rapidly rounded up and transported hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews to Nazi concentration camps, where most died.

After the fall of the Szálasi regime, Béla Miklós's Soviet-backed government was left nominally in control of the entire country. The High National Council, appointed in January to assume the Regency, included members of the Hungarian Communist Party, like Ernő Gerő, and later Mátyás Rákosi and László Rajk.

Economy

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

By topic |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Upon the kingdom's establishment soon after World War I, the country suffered from economic decline, budget deficits, and high inflation as a result of the loss of economically important territories under the Treaty of Trianon, including Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia.[18] The land losses of the Treaty of Trianon in 1920 caused Hungary to lose agricultural and industrial areas, making it dependent on exporting products from what agricultural land it had left to maintain its economy. Prime Minister István Bethlen's government dealt with the economic crisis by seeking large foreign loans, which allowed the country achieve monetary stabilization in the early 1920s. He introduced a new currency in 1927, the pengő.[19] Industrial and farm production rose rapidly, and the country benefited from flourishing foreign trade during most of the 1920s.[18]

Following the start of the Great Depression in 1929, the prosperity rapidly collapsed in the country, especially in part due to the economic effects of the failure of the Österreichische Creditanstalt bank in Vienna, Austria.[20] From the mid-1930s to the 1940s, after relations improved with Germany, Hungary’s economy benefited from trade. The Hungarian economy became dependent on that of Germany.

Foreign policy

Initially, despite a move towards nationalism, the new state under Regent Horthy in an effort to prevent further immediate conflicts signed the Treaty of Trianon on June 4, 1920, thereby reducing Hungary’s size substantially: Transylvania was taken by Romania; Upper Hungary became part of Czechoslovakia; Vojvodina was assigned to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (Yugoslavia after 1929); and the Free State of Fiume was created.

With the succession of increasingly nationalist Prime Ministers, Hungary steadily came to oppose the Treaty of Trianon, and aligned itself with Europe's two fascist states, Germany and Italy, which both opposed the changes to national borders in Europe at the end of World War I. Italian Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini sought closer ties with Hungary, beginning with the signing of a treaty of friendship between Hungary and Italy on April 5, 1927.[21] Gyula Gömbös was an open admirer of the fascist leaders.[22] Gömbös attempted to forge closer trilateral unity between Germany, Italy and Hungary by acting as an intermediary between Germany and Italy whose two fascist regimes had nearly come to conflict in 1934 over the issue of Austrian independence. Gömbös eventually persuaded Mussolini to accept Hitler's annexation of Austria in the late 1930s.[21] Gömbös is said to have coined the phrase "axis", which he applied to his intention to create an alliance with Germany and Italy; those two countries used it to term their alliance as the Rome–Berlin axis.[22] Just prior to the Second World War, Hungary benefited from its close ties with Germany and Italy when the Munich Agreement obligated Czechoslovakia and Hungary to arrange their territorial affairs by negotiations. Finally the First Vienna Award reassigned the southern parts of Czechoslovakia to Hungary, shortly after Czechoslovakia was abolished, Hungary occupied and annexed the remainder of Carpatho-Ukraine.

World War II

After the successful revision policy Hungary sought further solutions to the remainder of its former territories and demanded the concession of Transylvanian territory from Romania. The Axis powers were not interested in opening a new conflict in Central Europe; both countries were facing strong diplomatic pressures to avoid any military operations. Finally both parties accepted the arbitration of Germany and Italy, known as the Second Vienna Award, and as a result Northern Transylvania was assigned to Hungary. Shortly afterward, the Kingdom of Hungary joined the Axis powers. Hitler demanded that the Hungarian government follow Germany’s military and racial agenda to avoid potential conflict in the future. Anti-Semitism was already an established political cause by the far right in Hungary. In 1944, after the ousting of Horthy by Hitler and before the installation of the National-Socialist Arrow Cross party, the Hungarian government readily aided Nazi Germany in the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Jews to concentration camps during the Holocaust, where most of them died.

In April 1941, Hungary let the Wehrmacht into her territory, thus supporting Germany and Italy in the invasion of Yugoslavia. After the Independent State of Croatia was proclaimed, Hungary joined the military operations and was allowed to annex the Bačka (Bácska) region in Vojvodina, which had a relative majority of Hungarians, as well as the region of Muraköz (present-day Prekmurje and Medjimurje), which had large Slovenian and Croatian majorities, respectively.

On 27 June 1941, László Bárdossy declared war on the Soviet Union. Fearing a potential turn of support to the Romanians, the Hungarian government sent armed forces to support the German war effort during Operation Barbarossa. This support cost the Hungarians dearly. The entire Hungarian Second Army was lost during the Battle of Stalingrad.

By early 1944, with Soviet forces fast advancing from the east, Hungary was caught attempting to contact the British and the Americans to secretly escape of the war and establish an armistice with the Allies. On 19 March 1944, the Germans responded by invading Hungary in Operation Margarethe. German forces occupied key locations to ensure Hungarian loyalty. They placed Horthy under house arrest and replaced Prime Minister Miklós Kállay with a more pliable successor. Döme Sztójay, an avid supporter of the Nazis, became the new Hungarian Prime Minister. Sztójay governed with the aid of a Nazi military governor, Edmund Veesenmayer.

By October of the same year, the Hungarians were again caught trying to switch sides, and the Germans launched Operation Panzerfaust. They replaced Horthy with Arrow Cross leader Ferenc Szálasi. A new pro-German "Government of National Unity" was proclaimed, and it continued the war on the side of the Axis. Szálasi did not replace Horthy as Regent, but was appointed as the "Nationleader" (Nemzetvezető) and Prime Minister of the new Hungarian Fascist regime. There has been some debate as to what extent the Hungarian state of the 1930s and '40s can be classified as fascist. However, the regime's increasing economic dependence on Germany, its passage of anti-Semitic legislation and its participation in exterminating local Jews all place it within the realm of international fascism.[23]

On 21 December 1944, a Hungarian "Interim Assembly" met in Debrecen, with the approval of the Soviet Union. This assembly elected an interim counter-government headed by Béla Miklós, the former commander of the Hungarian First Army. At the end of March 1945, Szálasi's regime was driven out of Hungary.[24]

Dissolution

Under Soviet occupation and provisional governments, the fate of the Kingdom of Hungary was already determined. A High National Council was appointed the country's collective Head of State until the monarchy was formally dissolved on 1 February 1946. The Regency was replaced by the Second Hungarian Republic. It was quickly followed by the creation the People's Republic of Hungary.

See also

- Hungary between the World Wars

- Hungary during World War II

- Allied powers of World War II

- Axis powers of World War II

- Hungarian volunteers in the Winter War

Notes

^ The Allied powers generally did not recognize territorial evolutions of the Axis powers after the outbreak of World War II, however, it was not applied in all cases after the end of the war. De jure, generally the Axis powers recognized the territorial evolutions of its powers. Special exceptions - also regarding non-belligerent parties - may be possible.

- ↑ Adeleye, Gabriel G. (1999). World Dictionary of Foreign Expressions. Ed. Thomas J. Sienkewicz and James T. McDonough, Jr. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-86516-422-3.

- ↑ Dr. Térfy, Gyula, ed. (1921). "1920. évi I. törvénycikk az alkotmányosság helyreállításáról és az állami főhatalom gyakorlásának ideiglenes rendezéséről.". Magyar törvénytár (Corpus Juris Hungarici): 1920. évi törvénycikkek (in Hungarian). Budapest: Révai Testvérek Irodalmi Intézet Részvénytársaság. p. 3.

- ↑ Kollega Tarsoly, István, ed. (1995). "Magyarország". Révai nagy lexikona (in Hungarian). Volume 20. Budapest: Hasonmás Kiadó. pp. 595–597. ISBN 963-8318-70-8.

- ↑ Kollega Tarsoly, István, ed. (1996). "Magyarország". Révai nagy lexikona (in Hungarian). Volume 21. Budapest: Hasonmás Kiadó. p. 572. ISBN 963-9015-02-4.

- ↑ Élesztős László; et al., eds. (2004). "Magyarország". Révai új lexikona (in Hungarian). Volume 13. Budapest: Hasonmás Kiadó. pp. 882, 895. ISBN 963-9556-13-0.

- ↑ Kollega Tarsoly, István, ed. (1995). "Magyarország". Révai nagy lexikona (in Hungarian). Volume 20. Budapest: Hasonmás Kiadó. pp. 595–597. ISBN 963-8318-70-8.

- ↑ Kollega Tarsoly, István, ed. (1996). "Magyarország". Révai nagy lexikona (in Hungarian). Volume 21. Budapest: Hasonmás Kiadó. p. 572. ISBN 963-9015-02-4.

- ↑ Élesztős László; et al., eds. (2004). "Magyarország". Révai új lexikona (in Hungarian). Volume 13. Budapest: Hasonmás Kiadó. pp. 882, 895. ISBN 963-9556-13-0.

- ↑ Seamus Dunn, T.G. Fraser. Europe and Ethnicity: The First World War and Contemporary Ethnic Conflict. Routledge, 1996. P97.

- ↑ Sinor, Denis. 1959. History of Hungary, London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. Pp. 289

- ↑ Sinor, p. 289

- ↑ Kovács, Mária (2012). "The Hungarian numerus clausus: ideology, apology and history, 1919-1945". In Karady, Victor; Nagy, Peter. The numerus clausus in Hungary: Studies on the First Anti-Jewish Law and Academic Anti-Semitism in Modern Central Europe. Budapest: Centre for Historical Research, History Department. p. 28. ISBN 978-963-88538-6-8.

- ↑ See: Numerus Clausus

- ↑ "A Numerus Clausus módosítása - The modification of the Numerus Clausus law". "http://regi.sofar.hu".

- 1 2 Romsics, Ignác. "Nyíltan vagy titkosan? A Horthy-rendszer választójoga". "www.rubicon.hu". RUBICONLINE.

- ↑ Budapesti Közlöny, 17 October 1944

- ↑ Hivatalos Közlöny, 27 January 1945

- 1 2 Signor, pp. 290

- ↑ Signor, pp. 290.

- ↑ Signor, pp. 291.

- 1 2 Sinor, pp. 291.

- 1 2 Sinor, pp. 291

- ↑ Richard Griffiths, Fascism, p. 107, 111. London: Continuum, 2005. ISBN 0-8264-7856-5

- ↑ Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism, 1914-1945, Routledge, 1996, page 420

| Preceded by |

Kingdom of Hungary also known as the Regency 1920–1946 |

Horthy regime (1920–1944)

succeeded by |

Coordinates: 47°29′N 19°02′E / 47.483°N 19.033°E

.svg.png)

.svg.png)