Kinderhook plates

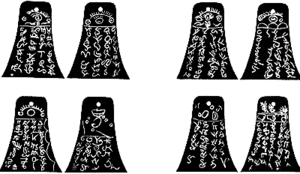

The Kinderhook plates were a set of six small, bell-shaped pieces of brass with strange engravings which were claimed to have been discovered in 1843 in an Indian mound near Kinderhook, Illinois.

According to Wilbur Fugate in 1879,[1] the plates were carefully forged by himself and two other men (Bridge Whitten and Robert Wiley) from Kinderhook who were testing the validity of the claims made by Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, at that time headquartered in Nauvoo. According to Latter Day Saint belief, the Book of Mormon was originally translated by Smith from a record engraved on golden plates by ancient inhabitants of the Americas.

Purported discovery

On April 16, 1843, Robert Wiley, a merchant living in Kinderhook, began to dig a deep shaft in the center of an Indian mound near the village. It was reported in the Quincy Whig that the reason for Wiley's sudden interest in archaeology was that he had dreamed for three nights in a row that there was treasure buried beneath the mound.[2] At first, he undertook the excavation alone, and reached a depth of about ten feet[3] before he abandoned the work, finding it too laborious an undertaking. On April 23, he returned with a group of ten or twelve companions to assist him. They soon reached a bed of limestone, apparently charred by fire; another two feet down, they discovered human bones, also charred, and "six plates of brass of a bell shape, each having a hole near the small end, and a ring through them all, and clasped with two clasps". A member of the excavation team, W. P. Harris, took the plates home, washed them, and treated them with sulphuric acid. Once they were clean, they were found to be covered in strange characters resembling hieroglyphics.[3]

The plates were briefly exhibited in the city, and then sent on to Joseph Smith, the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement. Twenty years earlier, on September 22, 1823, Smith claimed to have uncovered a set of golden plates, and, according to Latter Day Saint belief, translated them into the Book of Mormon. The finders of the Kinderhook plates, and the general public, were keen to know if Smith would be able to decipher the symbols on the Kinderhook plates as well.[2] The Times and Seasons, a Latter Day Saint publication, claimed that the existence of the Kinderhook plates lent further credibility to the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.[4]

Smith's response

Smith's private secretary, William Clayton, recorded that upon receiving the plates, Smith sent for his "Hebrew Bible & Lexicon",[5] suggesting that he was going to attempt to translate the plates by conventional means, rather than by use of a seer stone or direct revelation.[6] On 1 May, Clayton wrote in his journal:[7]

I have seen 6 brass plates ... covered with ancient characters of language containing from 30 to 40 on each side of the plates. Prest J. [Joseph Smith] has translated a portion and says they contain the history of the person with whom they were found and he was a descendant of Ham through the loins of Pharaoh king of Egypt, and that he received his kingdom from the ruler of heaven and earth.

The History of the Church also states Smith said the following:[8]

I have translated a portion of [the plates] and find they contain the history of the person with whom they were found. He was a descendant of Ham, through the loins of Pharaoh, king of Egypt, and that he received his kingdom from the ruler of heaven and earth.

Stanley B. Kimball claims the statement found in History of the Church was only an altered version of William Clayton's statement, placing Smith in the first person.[9] Diane Wirth, writing in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon (2:210), states: "A first-person narrative was apparently a common practice of this time period when a biographical work was being compiled. Since such words were never penned by the Prophet, they cannot be uncritically accepted as his words or his opinion".[10]

Rediscovery, analysis, and classification as a hoax

The Kinderhook plates were presumed lost, but for decades The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) published facsimiles of them in its official History of the Church. In 1920, one of the plates came into the possession of the Chicago Historical Society (now the Chicago History Museum).[9] In 1966, this remaining plate was tested at Brigham Young University. The inscriptions matched facsimiles of the plate published contemporaneously, but the question remained whether this was an original Kinderhook plate, or a later copy.

Though there was little evidence of whether the Kinderhook Plates were ancient or a contemporary fabrication, some within the LDS Church believed them to be genuine. The September 1962 Improvement Era, an official magazine of the church, ran an article by Welby W. Ricks stating that the Kinderhook plates were genuine.[11] In 1979, apostle Mark E. Petersen wrote a book called Those Gold Plates!. In the first chapter, Peterson describes various ancient cultures that have written records on metal plates. Then Peterson claims: "There are the Kinderhook plates, too, found in America and now in the possession of the Chicago Historical Society. Controversy has surrounded these plates and their engravings, but most experts agree they are of ancient vintage."[12]

In 1980, Professor D. Lynn Johnson of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Northwestern University examined the remaining plate. He used microscopy and various scanning devices and determined that the tolerances and composition of its metal proved entirely consistent with the facilities available in a 19th-century blacksmith shop and, more importantly, found traces of nitrogen in what were clearly nitric acid-etched grooves. This matches what was stated in an 1879 letter to James T. Cobb, in which Wilbur Fugate confesses to the hoax: "Wiley and I made the hieroglyphics by making impressions on beeswax and filling them with acid and putting it on the plates. When they were finished we put them together with rust made of nitric acid, old iron and lead, and bound them with a piece of hoop iron, covering them completely with rust". According to Fugate, Wiley had planted the plates at the bottom of the hole he had dug in the mound, before fetching a group of others to witness the discovery.[13]

In addition, Johnson discovered evidence that this particular plate was among those examined by early Mormons, including Smith, and not a later copy. One of the features of the plate was the presence of small dents in the surface caused by a hexagonally-shaped tool. Johnson noticed that one of these dents had inadvertently been interpreted in the facsimile as a stroke in one of the characters. If the plate owned by the Chicago Historical Society had been a copy made from the facsimiles in History of the Church, that stroke in that character would have been etched, like the rest of the characters. He concluded that this plate was one that Smith examined, that it was not of ancient origin, and that it was in fact etched with acid, not engraved.[9]

In 1981, the official magazine of the LDS Church ran an article stating that the plates were a hoax. In it, the author claimed that there was no proof that Smith made any attempt to translate the plates: "There is no evidence that the Prophet Joseph Smith ever took up the matter with the Lord, as he did when working with the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham".[9]

See also

Notes

- ↑ McKeever, Bill; Shafovaloff, Aaron. "Fooling the Prophet with the Kinderhook Plates". MRM.org. Mormonism Research Ministry. Retrieved 2013-01-17.

- 1 2 Bartlett & Sullivan (May 3, 1843). "Singular Discovery – Material for another Mormon Book". Quincy Whig. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- 1 2 Harris, W.P. (May 1, 1843). "To the Editor of the Times and Seasons". Times and Seasons. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ↑ "Ancient Records". Times and Seasons. 1 May 1843. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ↑ Smith, Joseph (1843), Diary, LDS Church Archives

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark (2003), "A One-sided View of Mormon Origins", The FARMS Review, 15 (2): 320, retrieved 2015-01-19

- ↑ Tanner, Jerald; Tanner, Sandra. "The Kinderhook Plates: Excerpt from Answering Mormon Scholars Vol 2". Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- ↑ History of the Church, Vol. 5, p. 372.

- 1 2 3 4 Kimball, Stanley B (August 1981), Kinderhook Plates Brought to Joseph Smith Appear to Be a Nineteenth-Century Hoax, Ensign, pp. 66–74, retrieved 2011-03-01

- ↑ Diane E. Wirth (1990). "[Review of] Are the Mormon Scriptures Reliable?". Review of Books on the Book of Mormon. FARMS. 2 (1): 210. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- ↑ Ricks, Welby W. (September 1962), "The Kinderhook Plates", Improvement Era, 65 (09): 636–637, 656–660

- ↑ Petersen, Mark E. (1979). Those Gold Plates!. Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft. p. 3. ISBN 0-88494-364-X.

- ↑ Welby W. Ricks "The Kinderhook Plates", cited in An Insider's View of Mormon Origins by Grant H. Palmer.

Further reading

- Ashurst-McGee, Mark (May 1996). Joseph Smith, the Kinderhook Plates, and the Question of Revelation. Mormon History Association conference. Snowbird, Utah. OCLC 51034002. [Held in the library collections of Brigham Young University and the University of Utah.]

- Bradley, Don (August 5, 2011). 'President Joseph Has Translated a Portion': Solving the Mystery of the Kinderhook Plates (PDF). 2011 FAIR Conference. Sandy, Utah: Foundation for Apologetic Information & Research (FAIR).

- Harris, W. P. (July 1912). "A Hoax: Reminiscences of an Old Kinderhook Mystery". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 5 (2): 271–73.

- Hauglid, Brian M. (2011). "Did Joseph Smith Translate the Kinderhook Plates?". In Millet, Robert L. No Weapon Shall Prosper: New Light on Sensitive Issues. Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University. pp. 93–103. ISBN 978-0-8425-2794-1.

- Hunter, J. Michael (Spring 2005). "The Kinderhook Plates, the Tucson Artifacts, and Mormon Archeological Zeal". Journal of Mormon History. 31 (1): 31–70.

- Peters, Jason Frederick (2003). "The Kinderhook Plates: Examining a Nineteenth-Century Hoax". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 96 (2): 130–45.

External links

- "Wasn't Joseph Smith fooled by the fraudulent Kinderhook Plates? Doesn't that prove he didn't translate by the power of God?" by Jeff Lindsay (apologetic)

- Kinderhook Plates (MormonWiki.org) - Evangelical Christian perspective

- Kinderhook plates, (MormonWiki.com) - unofficial LDS perspective